Editor’s note: This article appears in the Winter 2023 issue of Education Next.

Editor’s note: This article appears in the Winter 2023 issue of Education Next.

In June 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Carson v. Makin that Maine violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment by excluding religious schools from a private-school-choice program—colloquially known as “town tuitioning”—for students in school districts without public high schools.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts concluded that “the State pays tuition for certain students at private schools—so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion.”

Carson was, in some ways, unremarkable. For the third time in five years, the court held that the Constitution prohibits the government from excluding religious organizations from public-benefit programs, because religious discrimination is “odious to our Constitution.” But the fact that Carson was not groundbreaking does not mean that it is not important.

On the contrary, Carson represents the culmination of decades of doctrinal development about constitutional questions raised by programs—including parental-choice programs—that extend public benefits to religious institutions. Among the most important of these questions is whether there is “play in the joints” between the First Amendment’s religion clauses—the Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause—that might permit government discrimination against religious institutions in some situations.

Going forward, the answer in almost all cases is likely to be no. Both clauses, the court has now made clear, require government neutrality and prohibit government hostility toward religious believers and institutions. (The court clarified—but did not overturn—its 2003 decision in Locke v. Davey. In that case, the justices upheld, by a vote of 7–2, a Washington State law prohibiting college students from using a state-funded scholarship to train for the ministry; that law, the court ruled, did not violate the Free Exercise clause.

Arguably, Carson narrows and effectively confines Locke to its facts by characterizing it as advancing only the “historic and substantial state interest” against using “taxpayer funds to support church leaders.”)

Carson does, however, leave at least two important questions unanswered. The first concerns the decision’s scope. The holding makes explicit that “a State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.” Carson is silent, however, on what it means for the government to “subsidize private education.”

In particular, it leaves unanswered the question of whether the nondiscrimination mandate applies to charter schools, which are privately operated but designated “public schools” by law in all states—and supported by tax dollars. Does the Free Exercise Clause require states to permit religious charter schools?

The second question concerns which regulations states may lawfully impose as a condition of participation in private-school-choice programs. Right after the court issued its decision, for example, Maine’s attorney general, Aaron Frey, clarified that all private schools taking part in the program, including religious schools, are bound by the Maine Human Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

To continue reading, click here.

The Gallos were one of several Vermont families who sued the state over its policy banning religious private schools from participating in town tuitioning programs offered in areas without public high schools. Photo courtesy of the Institute for Justice

Vermont residents who live in towns too small to operate district high schools may now use public funds to send their children to faith-based private schools.

The Education Agency of Vermont recently told school administrators that they must comply with a 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down a Maine law banning religious schools from participating in town tuitioning programs.

“Requests for tuition payments for resident students to approved independent religious schools or religious independent schools that meet educational quality standards must be treated the same as requests for tuition payments to secular approved independent schools or secular independent schools that meet educational quality standards,” the agency’s Sept. 13 letter said. A list of approved independent schools on the website showed 15 religious schools.

Rural and sparsely populated, Vermont and Maine have programs that offer scholarships to families in areas that don’t operate public high schools so they can send their kids to public or private schools elsewhere.

However, both states prohibited the money from being spent on religious schools, so parents who wanted a faith-based education for their kids were forced to pay out of pocket.

In 2018, a group of parents challenged the Maine program.

Several Vermont parents also filed similar lawsuits. In June 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit struck down the prohibition against religious schools in the case A.H. v. French, brought by four Catholic high school students, their parents, and the Diocese of Burlington.

However, the Maine lawsuit, Carson v. Makin, was the one that made it to the U.S. Supreme Court and settled the issue nationally.

In that case, the high court ruled that education choice programs could not exclude schools based on religious instruction or activities, calling it “discrimination against religion.” A landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 2020, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, struck down bans on education choice scholarships based on a school’s religious status but stopped short of addressing the issue of religious use.

The Supreme Court ruling in the Maine case reverberated across Vermont, and was cited as the reason for the policy change there.

The decision also drew praise from the American Federation for Children, a national education choice advocacy group.

“Every family deserves the right to choose the best K-12 education for their children, and we are encouraged to see the Vermont Agency of Education stipulate that families in tuitioning programs can choose religious schools,” said Shaka Mitchell, the federation’s director of state strategy and advocacy. “After a hard-fought battle in Maine, the Supreme Court has resoundingly confirmed this right, and we are thrilled that Vermont families will be able to access a fuller range of options as well. We hope other states will join Vermont and follow the ruling of the Supreme Court by ensuring all students can learn in the educational setting that best meets their needs.”

Maine Attorney General Aaron Frey responded to the Carson v. Makin ruling with a statement that schools must comply with the Maine Human Rights Act to receive funds. That law bans discrimination based on race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or disability, which contradicts some schools’ religious beliefs. As a result, the two schools that were part of that case have refused to participate in the tuitioning program.

However, Cheverus High School, a Jesuit college preparatory school in Portland, this week became Maine’s first religious school approved for funding. Though a Catholic school, Cheverus is not governed by the Diocese of Portland.

The argument in Carson v. Makin is over Maine’s tuition assistance program, which pays for students in towns without a public school to attend another one of their choice — public or private — as long as it’s not religious.

This letter to the editor from Kirby Thomas West, a lawyer for the Institute for Justice who lives in Alexandria, Va., appeared Monday on washingtonpost.com. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

In her Dec. 7 opinion essay, “Taxpayers should not fund religious education,” Rachel Laser claimed that the issue before the Supreme Court in Carson v. Makin is whether taxpayers can be forced to fund religion.

Instead, the issue is whether, if a state creates a school-choice program, it can bar parents from choosing religious schools for their children. Notably, no one in the case is arguing that states have to create school-choice programs — only that if they do, they must not discriminate against religion.

In 2002, the Supreme Court recognized that school-choice programs, because they rely on parental choice and are neutral toward religion, do not violate the establishment clause. Curiously, Ms. Laser failed to mention this well-established principle of constitutional law.

(Or that school choice programs, including religious options, have been the norm for decades, including in D.C., with none of the “religious coercion” parade of horribles she warns about.)

Instead, Ms. Laser suggested that Carson could have a negative impact on state anti-discrimination laws that protect LGBTQ individuals. But such laws aren’t at issue in the case, which is evidenced by the fact that even if a school welcomes LGBTQ students, Maine says it need not apply to the program if it provides a religious education. The only discrimination at issue in Carson is religious discrimination.

Ms. Laser apparently wants the court to perpetuate this discrimination. For the sake of parents seeking better educational opportunities for their children, let’s hope she’s wrong.

Editor’s note: This commentary appeared Wednesday on The 74. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

Editor’s note: This commentary appeared Wednesday on The 74. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

Maine allows private religious schools to participate in its tuition benefit program for families that don’t have a public high school in their communities — except those that seek to instill religious beliefs in their students.

That caveat is at the heart of Carson v. Makin, argued before the U.S. Supreme Court Wednesday, a case that is likely to determine whether states can continue to ban religious schools from publicly-funded choice programs. Based on the justices’ questioning, experts said Maine, and states with similar laws, would likely no longer be able to defend them.

“This absolutely discriminates against parents,” Michael Bindas, a senior attorney with the libertarian Institute for Justice, who represents the plaintiffs, told the court. The state is discriminating against religion, he added, because decisions about whether a school is too religious to participate is “based on the decision of a bureaucrat in Augusta.”

Christopher C. Taub, Maine’s chief deputy attorney general, countered that the state’s program is “religiously neutral” and only seeks to give families free public education “roughly equivalent” to what they would get in a district school.

Wednesday’s hearing was the second time in two years the Supreme Court has considered whether public funds can pay for students to attend religious schools as part of school choice programs — an issue that public school advocates argue is a clear violation of the First Amendment’s separation of church and state.

In 2020, the court ruled in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, that the state could not exclude a religious school from a tax credit scholarship program simply because it was religious. The question in Carson takes the issue a step further, asking the court if officials can still ban such schools if they spend state money to teach religion. The fine legal parsing revolves around the issue of “status vs. use” — in this case, the difference between an institution that has a religious affiliation and one that uses public money to promote religion.

To continue reading, click here.

David and Amy Carson of Maine, pictured here with their daughter, Olivia, are challenging a 41-year-old policy that that limits to secular schools a state program offering financial assistance to families seeking education choice for their children.

David and Amy Carson both graduated from Bangor Christian Schools, housed in a tidy, red brick building in Maine. In addition to core academic subjects like reading and math, the school emphasizes a “biblical worldview.” Chapel meets every Thursday, and students are required to take Bible classes.

So, when their daughter, Olivia, was born they knew where they would send her to school.

“She started there in day care and then went to pre-K and straight through,” recalled Carson, who, with her husband, proudly watched Olivia cross the graduation stage with her high school diploma in hand from their alma mater. “Only one other kid had been there as many years.”

Even though their daughter is headed to college, the Carsons hope their involvement in a legal challenge that reaches the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday will end what they consider discrimination against students who attend religious schools.

The Carsons live in Glenburn, a town with a population of 4,468 located near the center of the state and about 8.5 miles from Bangor. Though a district school offers an education to students in kindergarten through eighth grade, the town lacks a high school. Once students reach that level, they must look for a school in a neighboring town. A state program offers financial assistance to families who live in towns without a high school, even if they choose a private school.

But when Olivia reached ninth grade and became eligible, the Carsons and other families were barred from receiving any assistance. That’s because Maine law limits the program to secular schools. Schools that teach religion, or engage in religious activities such as chapel meetings, can’t be part of the program, called a town tuition program.

“That’s kind of ridiculous,” Carson said, adding that Bangor Christian’s annual tuition, which totals $5,450 per child (with discounts for multiple children) costs less than many of the other schools that are allowed to participate. “They would be paying twice as much as they would pay to send her to Bangor Christian.”

The Carsons, who own a residential construction firm, have always had to pay Olivia’s tuition and fees out of pocket. While they never considered the situation fair, they managed. They were concerned, however, about the kids who disappeared from class because their families could no longer afford tuition.

That’s why, when the Carsons, who were invited three years ago to help challenge the now 41-year-old policy, decided to sign on.

“Families were hesitant to get involved, so David said, ‘Well, we’re doing it,’” Carson said.

For the past three years, Carson v. Makin has moved through the court system, with the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the 1st Circuit siding with the state in October. A three-judge panel said that the program’s limited scope separated it from other programs in which courts ruled that those bans were unconstitutional.

Maine’s ban, they said, was based on the schools’ use of state aid for religious activities, not merely the school’s status. The U.S. Supreme Court settled the status question last year when it ruled in Espinoza v. Montana that a school could not be barred from participating in a state scholarship program simply for being a religious school.

For an analysis of each case, see here and here.

“The central question here remains whether parents will be able to select the best schools to meet their children’s needs—including religious schools that reinforce the values and beliefs so many of these parents seek to instill in their homes,” said Michael Bindas, senior attorney for the Institute for Justice, which is representing the plaintiffs. “The Constitution requires government neutrality toward religion, not hostility. Maine’s exclusion of religious options violates that constitutional command of neutrality.”

The high court is expected to decide in the next couple of weeks whether it will consider the case during its next term.

The Carsons hope for a victory, even though they won’t benefit personally. They want to help others who are sacrificing to send their kids to a school known for its small class sizes, strong academics and a close-knit community.

“We both grew up in families with limited funds,” Carson said. “If (our parents) had had the ability for us to go to school and not have to pay for it, it would have been a huge help to them. We’re just hoping this goes through.”

Once to every man and nation comes the moment to decide,

In the strife of Truth with Falsehood, for the good or evil side

-- J.R. Lowell

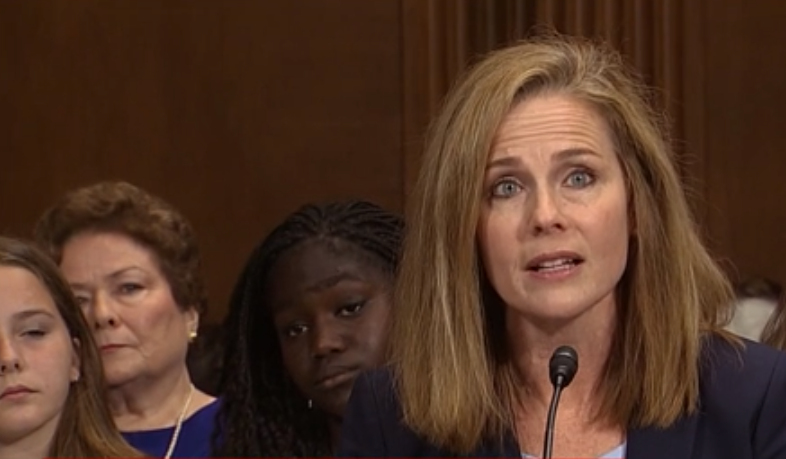

The president’s nominee for the open seat on the Supreme Court appears to be a highly qualified judge and scholar. She has set her moral convictions in the open, and, if not decisive, they are plainly relevant to the mission of this publication about parents and school.

Our constitution recognizes the legal sovereignty of the parent over the decision about who shall school their child. However, a century and a half of our country’s discrimination has denied choice to those parents who cannot afford either private school tuition or its equivalent in a freely chosen suburban institution where taxes play tuition’s role.

Judge Amy Coney Barrett clearly would prefer that society protect that same parental authority for the not-so-rich parents (and for the larger family) over who shall mentor this child.

The sudden opening of a place on the high court comes at a uniquely awkward moment. There is time, if properly managed, for the Senate to decide Judge Barrett’s future, and with it, (maybe) the basic legality of our conscription of the poor family for “public” school. The Court’s recent decisions on religious discrimination do suggest the possibility, and the appointment of Judge Barrett might advance the odds of such an historic stroke for human dignity.

Hence, the intense alarm of the teachers union leadership as it sees its monopoly over the poor at risk. No surprise; but what of the reaction of the Democratic Party (my own!)?

These self-declared defenders of the common folk are caught in a political seizure, even at one point declaring 50 days an unsuitably short time to decide who shall sit at the high bench – and, in any case, the fate of Judge Barrett, who could threaten the monopoly of the teachers union so valued by the Bidens.

May we ask ourselves: Observing this reality of Democratic dismay at the prospect of this nominee deciding cases, who is it here who is the voice for the poor? Are we who are registered Democrats supposed to be proud of our party, so unstrung at the prospect of a justice who just might support the actual exercise of the low-income parents’ right to choose? Who is it that is actually pulling for the poor here?

Obviously, there is time to decide, and this Democrat is pulling for Judge Barrett.

In 2002, in the Zelman case, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Cleveland school voucher program against a claim that the plan violates the “establishment clause” of the First Amendment to our national constitution. Simply put, the closely divided court concluded the Cleveland plan is part of a broader school choice scheme that in a number of ways gives families opportunities to select the schooling they believe is right for their children. That was understood to be the purpose and effect of the legislation and the fact that most of the vouchers were used at religious schools was beside the point. This decision shows a carefully constructed school voucher plan can survive a federal constitutional challenge.

Yet, voucher plans are still potentially illegal under state constitutional provisions that may be read by state courts to be more restrictive than the national constitution. States have very different provisions in their constitutions that voucher opponents cite in hopes of getting their state supreme courts to invalidate voucher plans. It is not possible to say what is the nationwide law on this issue because each state has its own separate constitution and because state supreme courts have in the past interpreted similar (or even identical) provisions of state constitutions in different ways.

This means that in every state where a school voucher plan is adopted there is likely to be a legal fight over its validity – as teachers’ unions, “separationists” who oppose anything they see as government aiding religion, and others who don’t like the voucher idea will go to court to try to win what they lost in the state legislature.

In March 2013, the Indiana Supreme Court, in the case of Meredith v. Pence, unanimously upheld the Indiana statewide school voucher plan against legal attacks in which opponents of the plan cited three different provisions of the Indiana state constitution. This was a big legal victory for supporters of the Indiana voucher plan, which at the time of the decision was serving about 9,000 students. (more…)

The Orlando Sentinel recently published a blog entry about a new website that opposes students using publicly-funded vouchers to attend private schools that teach creationism. The site asserts, “Teaching creationism with public money is unconstitutional. It violates the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution which lays out a clear separation of church and state.”

The Orlando Sentinel recently published a blog entry about a new website that opposes students using publicly-funded vouchers to attend private schools that teach creationism. The site asserts, “Teaching creationism with public money is unconstitutional. It violates the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution which lays out a clear separation of church and state.”

I’m fine with citizens opposing the teaching of creationism. I would not send my child to a school that taught creationism in lieu of evolution, but the assertion that it’s unconstitutional is false.

In the 1925 Pierce v. Society of Sisters decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled parents are responsible for determining how and what their children are taught. And in the 2002 Zelman v. Simmons-Harris decision, the court ruled parents may use public money to pay for tuition at faith-based schools provided their choice is genuinely independent, and the funds go first to the parents and then to the school.

Florida’s school voucher programs all adhere to the Zelman requirement that funds go first to the parent and then the school, which is why using publicly-funded vouchers to attend faith-based schools is an exercise of the First Amendment’s freedom of religion clause, and not a violation of the Establishment Clause. (By the way, the term “separation of church and state” does not appear in the U.S. Constitution. That phrase was used by President Thomas Jefferson in a January 1, 1802 letter he wrote to the Danbury Baptist Association of Connecticut, reassuring them that he opposed the government interfering with their religious practices.)

The Sentinel wrote that some state officials think tax credit scholarships are more constitutional than vouchers because tax credit funds never touch the state treasury, but, again, the key to the Zelman decision is the path the funds travel to arrive at a faith-based school. Once public funds are given to the parents, they become less public and more private, which is why their expenditure is an exercise of religious freedom and not government-supported religion. (more…)