Studies have repeatedly found that competition from charter and private schools drives small but meaningful improvements in public schools' performance. But most of those studies look at individual states or school districts, so the Thomas B. Fordham Institute has made a laudable effort to gauge competitiveness nationally.

The think tank's new report crunches state and federal data to see which large districts across the country face the most competition from private and charter schools, as measured by the number of students in each district's geographic area enrolled in non-district options.

The data demonstrate dynamics we've covered on this blog for years: Florida school districts like Miami-Dade County Public Schools face heightening competition from charter schools and private school scholarship programs. And they've responded by improving outcomes and creating new options for their students.

As Fordham's Amber Northern and Mike Petrilli write in their foreword, "the whole 'school choice versus improving traditional public schools' debate presents a false dichotomy; we can do both at the same time. Indeed, embracing school choice is a valuable strategy for improving traditional public schools."

The Fordham data are disaggregated by race, and they show that while there is still unequal competition for students of different backgrounds, all students have gained access to more options.

In most parts of the country, charter schools have been the largest source of new competition, as they've grown rapidly while private school enrollment has stagnated. That's even true in Miami-Dade, the largest district in a state with the nation's largest private school scholarship programs.

It's true for students in Miami-Dade on average, but it's not true for all groups. Private schools have driven the increase in competition to serve specific groups of students, including Black students.

This jibes with a point that researchers David Figlio, Cassandra Hart and Krzysztof Karbownik made in a recent study of the impact of charter schools on competition in Florida: The "competitive forces induced by the presence of charter and private schools appear to be complementary," at least for some student outcomes. It's possible schools in different sectors cater to different groups of students.

There is a key limitation of Fordham's approach. The number of students who opt out of district schools is an imperfect indicator of competition. Private schools are booming in the San Francisco Bay area, but there's little evidence that districts are scrambling to compete for their students.

On the other hand, while Florida's private schools have grown slightly over the past two decades, the share of students using educational choice scholarships has grown faster. In other words, the mix of private-school students has shifted, and some students attending private schools now would have lacked the means to do so a decade or two earlier.

Studies detailing the resulting impact on public-school performance have shown that as Florida's scholarship programs scaled up, performance improved faster in schools that served more low-income students, and thus had to compete for students whose enrollment they could previously take for granted. In other words, an ideal measure of competition may not be the share of students who have left district schools, but the share of students who could leave, and who districts feel compelled to serve more effectively as a result.

If there was any doubt about where microschools currently stand in the hype cycle, critics on the left are now being joined by worriers on the right.

Daniel Buck of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute recently reflected on his visit to a conference hosted by Harvard University that highlighted the rise of microschools and other learning environments that defy the conventions of schooling.

He describes seeing "much to love" about these small independent learning communities, but also notes a troubling "ideological undercurrent" among many of the educators who animate it, including an infatuation with progressive and student-led pedagogies.

In a compelling piece a few months ago in these pages, veteran homeschooling mom Larissa Phillips details the movement’s infatuation with unschooling, a theory of education (if we could call it that) that postulates that, if we just let kids be, they’ll follow their own passions to success. She details parents arguing about whether kids should be expected to follow basic rules, attend classes that they don’t like, or bother getting out of bed if they didn’t feel like it that day.

. Inquiry learning, project-based learning, self-directed learning, and other models of a similar stripe abound. The center’s founder argues that this preference for self-direction is inherent in the model’s rejection of systematization. In an interview with the New York Times, Jerry Mintz, the founder of Alternative Education Resource Organization, an institution that supports microschools and independent schools, shares a similar sentiment: “Kids are natural learners, and the job of the educator is to help kids find resources; they are more guides than teachers.”

Color me skeptical.

The philosophy drawing Buck's skepticism was famously summed up by Plutarch: "The mind is not a vessel that needs filling, but wood that needs igniting."

There's a reason this kind of thinking takes root among microschools, homeschoolers, and others operating outside the public education system.

If the past 200 years of American public education were a battle between the vessel-fillers and the fire-igniters, the vessel-fillers have won in a rout. Compulsory schooling laws, accountability systems tied to standardized tests, and a grammar of schooling that assumes teachers lead classes of students with desks lined up in rows are all victories of the bucket-fillers.

The fire-lighters have been pushed to the margins, where they wage a guerilla campaign that waxes and wanes over decades. The last great insurgency came during the '60s and '70s, when the "freed school" movement spawned a proliferation of small independent learning communities across the country.

Scholars who documented free schools noted they appeared to have two major flavors: One led by hippy types committed to progressive student-directed pedagogies, the other led by African Americans who critiqued a public education system that they felt mistreated their children. The former were committed fire-lighters; the latter were more amenable to vessel-filling.

The freedom school movement died off over the past few decades (though a few live on). Both its major strands are present in the new wave of microschools, hybrid homeschools, and other small learning communities operating outside public education that has gained momentum after the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the current wave includes other ideological currents, some of which conservatives like Buck will likely find more amenable, like commitments to religious instruction or classical education.

A crude account of the appeal of classical education is that it critiques public education from the direction opposite the progressive fire-lighters, arguing conventional schools fail to instill virtue in young people or fill their vessels with sufficient knowledge of the great cultural works of Western civilization.

In short, the educational philosophies animating the current microschool movement are all over the ideological and pedagogical spectrum. But they have one important thing common: They reject some of the prevailing norms in public education. They are intentionally creating models that are, in some way, different.

So, while Buck makes important points about the need for educators operating in permissionless learning environments to continually examine their methods and improve their practice, it's also essential to recognize that the movement is likely never to reach consensus on some fundamental beliefs about what education ought to look like. That's a feature, not a bug.

Broken Promise?

iPromise Academy, LeBron James's widely publicized foray into educational transformation, is stumbling. Five years in, not one of its current eighth graders has passed the state's math test, and new results reported to the local school board show its students aren't even outperforming peers at other schools whose disadvantages qualify them for admission to the school.

[Akron School] Board President Derrick Hall, who noted Monday's presentation was the first such overview he had seen on the school in his nearly four years on the board, said he was disappointed with the data, even with COVID-19 and a year of remote learning as known factors, given the plethora of additional resources at the school.

"For me as a board member, I just think about all the resources that we're providing," Hall said. "And I just, I'm just disappointed that I don't think, it doesn't appear like we're seeing the kind of change that we would expect to see."

Why it matters: James drew accolades for partnering with the Akron school district, eschewing paths favored by other celebrity school reformers who create independent private or charter schools that students attend by choice. A turnaround might still be possible, but iPromise appears poised to join the list of highly publicized but ultimately unsuccessful efforts to improve outcomes for low-income students who are struggling academically.

Open to all

An insightful commentary published by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute suggests that enrollment declines could overturn the politics of scarcity in suburban public schools, and goad them to accept more students from outside their borders.

A number of factors have disrupted this way we’ve always done things—Covid-19, the baby bust, and lower immigration rates among them. Though districts in fast-growing metropolitan areas, like Sacramento, have avoided the worst effects of declining enrollment, other suburbs have not been as lucky. This is particularly true in suburbs that have historically relied on white student enrollment, which has declined by 5 percent nationwide (and by more than 20 percent in Ohio). These vast demographic shifts won’t end any time soon.

If suburban areas refuse to open their doors, these districts will have to make some tough choices. No district wants to shutter schools or lay off teachers due to declining enrollment. But without open enrollment, this is likely what many suburban districts will have to do. Operating schools at 50 or 60 percent capacity is simply unsustainable.

Why it matters: Exclusive suburban enclaves have often been recalcitrant about opening their public schools to all students, particularly students from neighboring urban districts.

Free the principals

A new working paper from Northwestern University economist Kirabo Jackson finds an initiative by Chicago Public Schools to give principals more power over their schools' budgets and operations yielded small but measurable performance improvements.

Why it matters: At a time when Americans are losing trust in institutions of all types, school principals are among the most trusted authority figures in America. As a group, their credibility took a hit during the Covid-19 pandemic, but they still hold deeper reservoirs of public esteem than politicians or the media. This can make them powerful allies in any reform strategy.

Mike McShane, who brought the paper to our attention, adds: "It is also a helpful reminder that there are few blanket policies that are good for all schools, all principals, all teachers, or all students. While autonomy could be good for a high-quality principal, it could be terrible for a low-quality one."

Numbers to Know

10: Percentage chance that a middle-income student scoring in the 99th percentile on the SAT will get admitted to one of 12 of the nation's most elite universities

40: Percentage chance that a student with similar scores in the top 1 percent of income-earners will gain admission to those same schools.

99,973: Enrollment decline in the nation's largest public school district, New York City Public Schools, over the past five years.

21,367: Enrollment jump in New York city's charter schools during the same period.

42: Number of the 50 states projected to see public-school enrollment declines in the coming years.

The Last Word

"This is the biggest domestic policy failure of our lifetime, in my humble opinion."

- 50CAN President Derrell Bradford, in congressional testimony on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and school closures on student learning.

Great Hearts Northern Oaks in San Antonio, Texas, is part of a system of state-chartered public schools that offer a tuition-free, liberal arts education rooted in the literary and philosophical tradition of the West. Great Hearts Northern Oaks students learn about historical events, literary characters, poetry, scientific facts and mathematical proofs.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Cassidy Syftestad, a doctoral academy fellow in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, and Albert Cheng, an assistant professor in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, appeared Thursday on The Fordham Institute’s website.

Recent shifts in enrollment patterns across Texas school sectors have gone in one direction—out of traditional public schools. Within those shifts, a disproportionately large swath of students has left for classical charter schools.

These trends reflect a wider renaissance of classical schooling across the United States. Parents from all manner of backgrounds increasingly sought out classical schools during the pandemic, but also beforehand. And that trend appears to be continuing.

In a new report, we use data from the Texas Education Agency and the National Center for Education Statistics to uncover exactly how much classical charters have grown in Texas since 2011 and the reasons behind such growth.

Texas is home to several classical charter schools. Great Hearts, Valor, and ResponsiveEd operate networks throughout the state. Other classical charters such as Houston Classical and Trivium Academy, though not part of larger networks, are well known in their respective communities.

What do these schools have in common? As Jennifer Frey explains on the Flypaper blog:

On this model, to become educated is, at least in part, to become a person of good character—to become habituated into recognizable patterns of correct thinking, acting, and feeling so that one is disposed to judge and choose well on the whole, in order to live a purposeful and meaningful life that contributes to the common good.

As depicted in Figure 1, Texas’s charter sector has grown dramatically in the past decade. However, the most prolific growth within the sector appears to be concentrated among classical charter schools. While enrollment in other Texas charters doubled between 2011 to 2021, enrollment in Texas classical charter schools increased nearly sevenfold to 20,000 students over the same period. Several thousand students remain on waitlists for seats in them.

The classical charter sector also grew along ethnic lines, with the most pronounced increase for Asian American (a thirteenfold increase) and Hispanic students (a ninefold increase).

To continue reading, click here.

Aaron Churchill, Ohio research director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, has released a new report on charter schools in his state for the institute.

Aaron Churchill, Ohio research director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, has released a new report on charter schools in his state for the institute.

Broadly speaking Churchill praises an effort that began in 2015 to tighten up accountability for authorizers, advocates for funding and other efforts to expand “quality” charters, and calls for funding equalization between brick-and-mortar district and charter schools.

Churchill writes: "Ohio can’t afford to slip back into the dark ages of lax accountability and anything-goes in the charter sector. Lawmakers need to maintain the commitment to accountability for sponsors and schools to ensure that student achievement remains a priority and that the performance of the sector continues its upward trend."

This bit of text in the study got your humble author’s attention: "Through much-needed reforms, state lawmakers have reinvented Ohio’s charter school sector. The Buckeye State is no longer the “wild west” of charter schools, as dozens of low-performing schools have closed, and more than forty sponsors have departed."

Out in Arizona, we take the “wild west” term as a badge of honor, given our remarkable results and the unfortunate stagnation of much of the rest of the charter movement. I don’t live in Ohio, and thus will offer no opinion on any of Chu’s recommendations. I will however offer a different perspective.

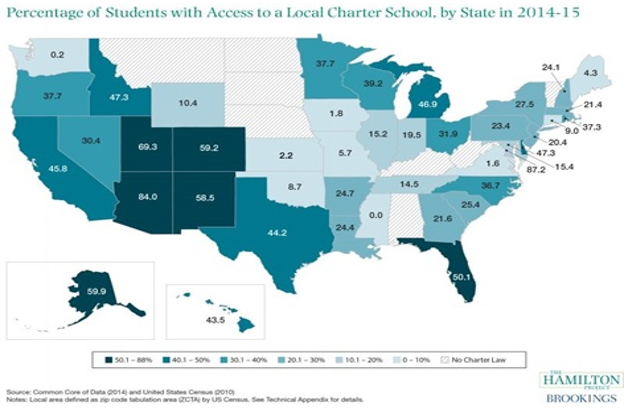

Let’s start with exhibit A, the Brookings charter school access map from 2014-15.

The map shows the percentage of students in each state with one or more charter schools operating in their ZIP code. Even before the 2015 reforms that Chu noted led to 100 Ohio charter schools eventually closing, the state’s charter school sector operated in fewer than one-third of all Ohio ZIP codes.

This was according to the initial design of the Ohio charter statute. Until a recent change in statute supported by both Fordham and yours truly effectively prevented charter schools outside urban areas.

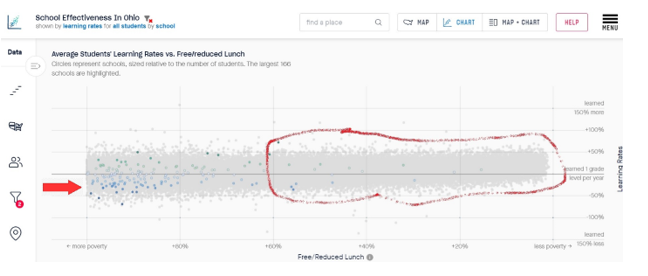

The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project has compiled academic achievement data on schools from around the nation by linking state exams. This chart shows the average rate of academic growth by school for Ohio charter schools, 2008-2018.

Figure 1: Average Academic Growth Rates for Ohio Charter Schools, 2008-2018 (Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project)

Figure 1: Average Academic Growth Rates for Ohio Charter Schools, 2008-2018 (Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project)

Two things to note: First, the circle. Ohio has very few charter schools with either median or low levels of student poverty. The lack of schools in the red circle constitutes further confirmation of the heavily geographically segregated nature of Ohio’s charter school sector seen in the Brookings map.

Second, note the red arrow. Ohio had a large number of high-poverty charter schools with low levels of average academic growth (blue dots below the “learned 1 grade level per year” line. This is disturbing. It means the already large achievement gaps grew in these schools over time.

Finally, take note of the blue-to-green dot ratio: High grow schools do not outnumber schools with low levels of growth.

Now, let’s compare Ohio’s geographically segregated charter sector to the nation’s most geographically inclusive charter sector in Arizona. As shown in the Brookings map, 84% of Arizona students had one or more charter schools operating in their ZIP code.

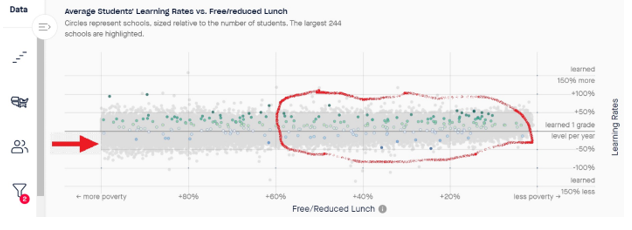

Figure 2: Average Academic Growth Rates for Arizona Charter Schools, 2008-2018 (Source: Stanford Educational Opportunity Project)

Look again in the red circle. Lots of charter schools and lots of charter schools with high levels of academic growth.

Next, let’s examine the high poverty area of the chart near the red arrow: very few low-growth schools.

Finally, notice the total ratio of green-colored schools to blue-colored schools in the entire chart. Arizona has high growth schools across the entire sector, relatively few low-growth schools.

Data from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools reveal that Arizona has a larger absolute number of urban charter schools than Ohio. How did the state avoid a large number of low-growth schools-urban or otherwise? Closures, but largely not of the administrative variety.

The Arizona State Board for Charter Schools listed 106 charter school closures between 2010 and 2014 and the reasons for the closures, a few more than the 100 closed in Ohio since 2015. The board describes a wide variety of reasons for closures including lack of enrollment, loss of a facility, merger with another charter, etc. The explanations are broad enough to require interpretation, but approximately 16 of the school closures involve a clear administrative action by the board to either close or merge.

Arizona charter schools that closed between 2000 and 2013 had an average tenure of operation of four years and an average of 62 students enrolled in the final year of operation for closed Arizona charters. Arizona law grants 15-year charters, but the competitive environment in Arizona closes charters early and often.

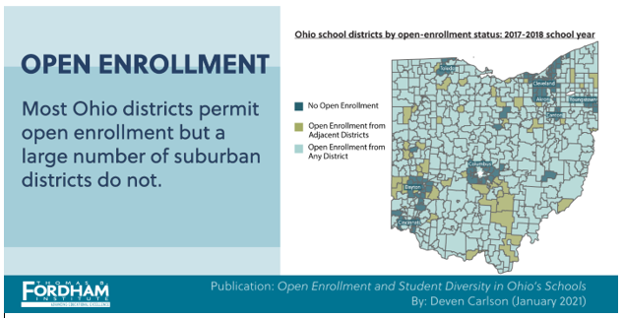

Why does Ohio have so many low-growth charter schools? I believe that this map from the Fordham Institute explains much of the difference between Ohio and Arizona:

Notice that not every suburban district in Ohio participates in open enrollment. Notice also the sickly, green-colored districts that only participate in open enrollment with adjacent districts. One can’t help but wonder just which students they might be trying to avoid.

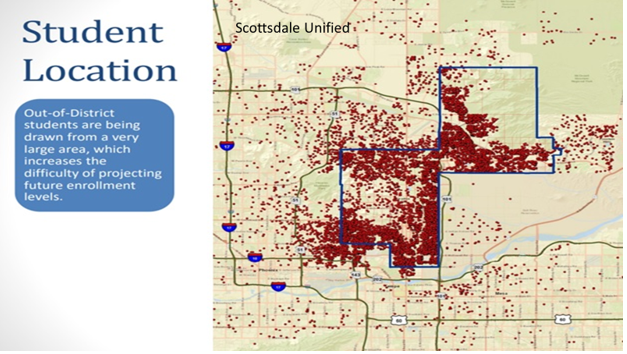

My theory is as follows. Low-growth urban charter schools survived in Ohio but quickly closed in Arizona because Arizona students have lots of other options. Nearly all Arizona school districts participate in open enrollment. This includes relatively affluent districts like Scottdale Unified, which brings in over one-quarter of its total enrollment from outside the district’s boundaries.

Scottsdale Unified enrolls approximately 20,000 students, with 4,500 students coming to the district through open enrollment. The 9,000 students who live within the boundaries of Scottsdale Unified who attend schools in charters, other districts, private schools, etc., doubtlessly play a large role in making open-enrollment opportunities available. Suburban districts in Arizona prefer to participate in open enrollment rather than close campuses.

Arizona’s suburban charter schools opened suburban districts to open enrollment, leading to closure of low-demand charter schools. This virtuous cycle does not have the chance of occurring in charter sectors constrained exclusively to urban areas.

Wisely, Ohio lawmakers recently expanded choice options by removing geographic restrictions on charters and expanding private choice options. The limitations of Ohio’s charter sector thus seem to owe more to poor central planning than to “wild west” liberality.

Author and podcast host Steven Berlin wrote: “The strange and beautiful truth about the adjacent possible is that its boundaries grow as you explore them. Each new combination opens up the possibility of new combinations.”

Arizona’s experience shows that choice programs, far from being siloed, interact with each other out in the field. Allowing families and teachers to shape the K-12 space is a much better idea than leaving it to state officials and is the best solution to the elimination of low-performing schools of any sort: more options.

Embracing liberality takes humility and wisdom, but without it, choice sectors quickly hit a low ceiling in serving the interests of the poor.

Ohio’s charter failure, by my way of thinking lies in central planning. The goal ought not be to replace bad central planning with better central planning. Rather, the goal should be to create a fully inclusive and demand-driven system of education that allows educators and families to act as the hands of a potter at a wheel, molding the K-12 space over time to create the types of schools educators want to run – and that families want to support.

Editor’s note: Michael J. Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, offers this introduction to the Institute's 2022 annual report. You can view the report here.

Editor’s note: Michael J. Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, offers this introduction to the Institute's 2022 annual report. You can view the report here.

| Lucy and the football.

Groundhog Day. “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.” Use whatever metaphor you like, but the pattern over the last several years has been clear: Just when we dare to believe we’ve escaped the pandemic, it grabs us once again, wreaking havoc in our lives, our schools, and the lives of our children. But 2022 was the year that we finally reached escape velocity. With the beginning of the new school year this past fall, things finally felt back to normal. Quarantines were mostly over, and masks were mostly gone, and classes and extracurricular activities were mostly back in full force. This fall was also when the education bill came due on America’s decision to shutter most schools for months on end as a cornerstone of our Covid policy. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, in two separate reports, documented the massive learning loss experienced by American students, enough to wipe out two decades’ worth of gains, and to widen our tragic achievement gaps into even larger chasms. These two developments—the end of the pandemic and the accounting of just how much damage it did—led to the same conclusion: Now it’s time to push the pedal to the metal on student learning. And that’s exactly what Fordham pressed for in 2022—nationally, in our home state of Ohio, and with the dozen charter schools we oversee. The highlights of those efforts are explained in our Annual Report. They feature initiatives directly related to pandemic recovery, including a book I published with two colleagues, “Follow the Science to School: Evidence-based Practices for Elementary Education,” as well as broader efforts to reboot the education reform movement. On that score, you’ll find details about Fordham’s latest research in our years-long study of charter schools, what makes them so effective, and how their expansion is also helping traditional public schools to improve. And you’ll read about our newer efforts to reimagine high schools, especially with an eye toward career readiness and upward mobility, and to ensure that advanced learners get what they need from their schools, too. I’m proud also to note that 2022 also marked Fordham’s 25th anniversary. We’re not into hoopla and self-congratulation, so we didn’t make a fuss, but Checker (Finn) has been spending some time digging into the archives to plot our trajectory since 1997. One important discovery is that we’ve stayed true to our policy North Star, despite all the changes of the past quarter-century. Our original “credo,” inherited from the Educational Excellence Network, had six “essential elements” for education reform: · The need for dramatically higher academic standards · An education system designed for and responsive to the needs of its users · Verifiable outcomes and accountability · Equality of opportunity · A solid core curriculum, taught by knowledgeable, expert instructors · Educational diversity, competition and choice We might tweak a word or two today, but those elements remain just as important now as back when Google launched its search engine. And we will pursue them, yet again, in the year ahead. |

United Preparatory Academy in Columbus, Ohio, with a minority student enrollment of 85%, is one of 375 charter schools in the state that serve an estimated 132,000 students.

Editor’s note: This analysis appeared last week on the74million.org.

Home to a sizable charter school sector and a host of private academies, Ohio is one of the friendliest environments for school choice anywhere in the country. Now, as courts and politicians decide the future of the state’s school voucher program, a study released in December indicates that private school choice hasn’t had the damaging impact that many of its detractors claim.

In fact, its author argues, racial segregation of students tended to decline in school districts where more students were eligible to receive vouchers from the state.

The report was commissioned by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a reform-friendly think tank with a special focus on research and advocacy in Ohio. Its arrival could help shape the debate over the effects of school vouchers and the course that the state’s ambitious choice agenda will take in 2023, though voucher critics may contest its findings on school funding.

Alleging that the public funding of private schools is unconstitutional, and that the current system “discriminates against minority students by increasing segregation in Ohio’s public schools,” a coalition of school districts sued the state last year. A Columbus judge rejected an effort by the government to dismiss the case just a few weeks after the Fordham report was issued.

At the same time, Republican lawmakers have revived an effort to massively expand the voucher program, known locally as EdChoice, to all of Ohio’s K–12 students after a similar move stalled in December.

Roughly 60,000 kids statewide receive EdChoice scholarships ($7,500 for high schoolers, $5,500 for younger children) to defray tuition costs at private schools, including religious institutions. That number has increased dramatically over the last decade, leading supporters of public schools to complain that their enrollment, finances, and academic offerings have been harmed by the rapid movement of families and funding from districts.

But study author Stéphane Lavertu, a political scientist at Ohio State University, argued that his research didn’t support those claims. The report shows that vouchers’ effects on student achievement and per-pupil funding in public schools are ambiguous, but not obviously negative — and far from increasing racial segregation in affected schools, he argued, EdChoice seems to actively decrease it.

“What we can say with some level of certainty is that segregation did not go up in district schools,” Lavertu said. “In fact, we can say with some confidence that it went down. That’s the only finding where I would say that there’s a clear direction, and it’s down.”

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This article from Jeff Murray, formerly of School Choice Ohio and the Greater Columbus Arts Council, appeared Thursday on the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s website.

Common sense, backed by research, tells us that families weigh a lot of information when making school choice decisions. This is especially true when options are readily available and easily comparable via centralized application systems.

Importantly, families’ calculations must be made anew each time a child moves schools, and it seems likely that the primary influencing factors can vary over time. New research investigates the stability of preferences by comparing choices made by the same families for younger and older children. It’s a quick but interesting look at familial decision making.

Harvard researcher Mark J. Chin uses application data from over 10,000 families applying for seats in both sixth and ninth grade in an unnamed large urban school district between the 2011–12 and 2018–19 school years. A majority of students in the district—and in the study—are Hispanic.

Via a unified enrollment system, families can rank up to five district options for each child. Assignment to schools is based on family preferences, available seats, admission priorities (including siblings), and random placement (if processing of the previous factors yields more than one valid option).

Chin’s work does not involve the actual offering or acceptance of seats in any particular school, but examines the preferences revealed by the schools ranked first in each family’s submissions.

Overall, all families selected as their top choice schools that were of higher quality than the average district building. This holds true for both middle and high school choices, although it is important to note that Chin does not define what “quality” means in this context.

White families chose schools that were whiter than both the average district building—middle and high schools—and the top choices of Hispanic and Black families. Similarly, Hispanic and Black families’ top choices served more students matching their racial/ethnic background than the average district building.

Black applicants chose middle and high schools that were further away from home than did their Hispanic and White peers.

To continue reading, click here.

The Cleveland Scholarship Program gives students in kindergarten through 12th grade the opportunity to attend private schools in Cleveland such as Heritage Christian School. Maximum scholarship amount for K-8 students is $5,500; maximum amount for high school students is $7,500.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jessica Poiner, senior education policy analyst at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, appeared last week on the institute’s website.

Persistent school choice critic Steve Dyer recently posted a “takedown” of Fordham’s latest school choice policy recommendations. His attacks mostly focus on Ohio’s voucher programs, and most of his criticism is tired and misleading enough that we’ve had to address it before. I won’t do so again here.

But buried among his many spurious arguments is a “recommendation” worth drawing attention to:

All voucher recipients have to attend the local public school for 180 days prior to applying for the voucher. If you’re going to take money away from public schools so kids they’ve “failed” can “escape” to private schools, shouldn’t you actually give the district a chance to succeed first?

It’s hard to know where to start with a statement that so unashamedly puts the financial needs of a system over the rights and wellbeing of people, namely kids. It is similarly difficult to fathom just how out of touch Dyer seems to be with anyone who might have had a negative experience with the district schools he champions.

So, let’s take it piece by piece.

“All voucher recipients have to attend the local public school for 180 days prior to applying for a voucher.”

At the risk of stating the obvious, 180 days is a whole school year. I say this because it’s important to realize that when Dyer recommends that state law require kids to attend their local public school for 180 days before they can access a voucher, he’s talking about an entire year of their lives.

It appears, given the rest of his piece, that he thinks this year will magically transform the wishes of any family who thinks that their child’s needs can best be met by a private school. But what happens if he’s wrong? Does Dyer have a plan to return to that family and that child the entire year’s worth of their lives he’s demanding? Doubtful.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Michael J. Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and executive editor of Education Next, appeared Thursday on the institute’s website. You can read the earlier commentary Petrilli references in the post here.

Earlier this month, I argued that education reform is alive and well, even if the Washington Consensus is dead for now. What’s more, I wrote that we should stay the course on the current reform strategy:

Keep growing charter schools. Keep expanding parental choice. Keep adopting high-quality instructional materials and keep getting teachers trained up on them. Keep testing students regularly and keep reporting the results. Keep being honest with parents and taxpayers about their students and schools are performing.

That was the too-simple version. Let me flesh out three key points:

I heard from a friend that my call to “stay the course” on the current reform agenda sounded “nostalgic in a way that feels like it might be clinging to something we have to rethink.” I can see why it might feel that way.

So, to clarify: The current ed reform agenda is not the same as 30 or 20 or even 10 years ago.

In the 1990s, for example, we were very focused on boosting the percentage of students scoring proficient on state tests – and, eventually, on seeing the “disaggregated data” move in the right direction.

The focus on disaggregated results remains, but thankfully we have largely moved passed a single-minded focus on proficiency, a “snapshot in time,” and toward greater attention to individual student growth.

By the early 2010s, much of the conversation was about holding individual teachers accountable via test-informed teacher evaluations. Ham-handed implementation and poisonous politics led us to leave that misguided reform behind.

On the other hand, an embrace of “high quality instructional materials” is rather new, enabled by the common set of standards for English language arts and mathematics still in place in most states.

No doubt, the agenda will continue to evolve, as well it should, informed by hard-earned, real-world experience, plus what we’re learning from rigorous research studies.

To continue reading, click here.