The hard work and determination of two South Florida mothers, along with support from Teach Florida, led to the launch of JEMS Academy in North Miami Beach. The school serves children with special needs, many of whom attend using Florida’s Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Like many worthy endeavors, it started with two determined moms.

Both Avigayil Shaffren and Shoshana Jablon had children with unique abilities. Shaffren’s son was born with cerebral palsy, which affected his left side. Jablon’s son was born with Down Syndrome and later was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Shaffren’s son attended a charter school for the first four years of his life. The program had its benefits, such as therapies and personal attention that she says he wouldn’t have received anywhere else. But when it came time to start kindergarten, she said, “it was awful.”

Despite her son being assigned a “shadow,” he made little progress. An evaluation turned up other diagnoses, which further complicated things. School officials gave Shaffren a choice: she could have her son repeat kindergarten or place him in a specialized school that would meet his educational needs.

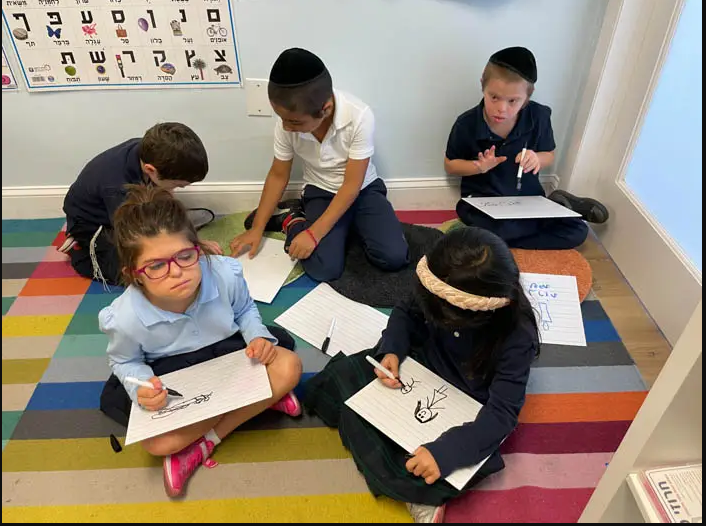

JEMS students, whose unique abilities vary widely, frequently help each other with assignments.

The Shaffrens chose to have him repeat kindergarten, but Shaffren, who is Orthodox Jewish, was concerned about her son’s religious educational needs, especially as he got older. Shortly thereafter, she was laid off her job. Though three months of unemployment brought hardship, it also offered an opportunity.

Shaffren turned to her friend, Jablon, who is also Orthodox Jewish, and said, “That’s it; we’re done. We need to create this school, and we’re not done until we create it.”

Shaffren spent the time she would have devoted to a paying job researching Jewish special education programs, such as OROT, which is the Hebrew word for light. Based in the Philadelphia suburb of Melrose Park, OROT (pronounced OR-oh) partners with four Jewish day schools to provide an integrated education for diverse learners.

Another was SINAI Schools in New York, which is based on a similar model as well as JEWELS, or Jewish Education Where Every Learner Succeeds, a Baltimore program that incorporates therapies into the school day.

Shaffren and Jablon developed a business plan, which Shaffren felt at the time was “a house of cards that was falling apart.”

But, through hard work, determination and support from Teach Florida, they opened JEMS Academy in a building across the street from its umbrella school, Toras Chaim Toras Emes in North Miami Beach.

“It was a miracle,” Shaffren said about the process, which the women said they completed right before the new school year was about to begin.

Though Shaffren’s son was able to start first grade and continue in the umbrella school, she continued to support JEMS, which stands for Jewish Education Made Special. This past year, JEMS opened its doors with five students.

Of those, four received the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities. The fifth student had applied but was on the waitlist. The founders say they expect that student to be awarded due to the additional funding and higher growth rates that state lawmakers allowed this year in HB 1.

According to Jablon and Shaffren, the students’ unique abilities vary widely. Staff members, who have advanced degrees in special education, personalize education to best fit each students’ needs. JEMS also provides onsite therapies. Jablon’s 10-year-old son, Nesanel, receives occupational and speech therapies there. The founders are seeking to add a Hebrew reading specialist and build a sensory room.

You can see a video of a typical day at JEMS here.

“It’s mushrooming, really growing,” Jablon said. “We just keep adding things as we see what the needs are.”

The program also includes a music program, which Jablon said serves as a type of therapy for students, some of whom experience anxiety or have autism. A staff member also brings a therapy dog.

“They really act as a cheering squad for one another,” she said. “If someone does something inappropriate, the whole class stops.”

She said it’s a real opportunity to develop social skills because they see how to act with one another.

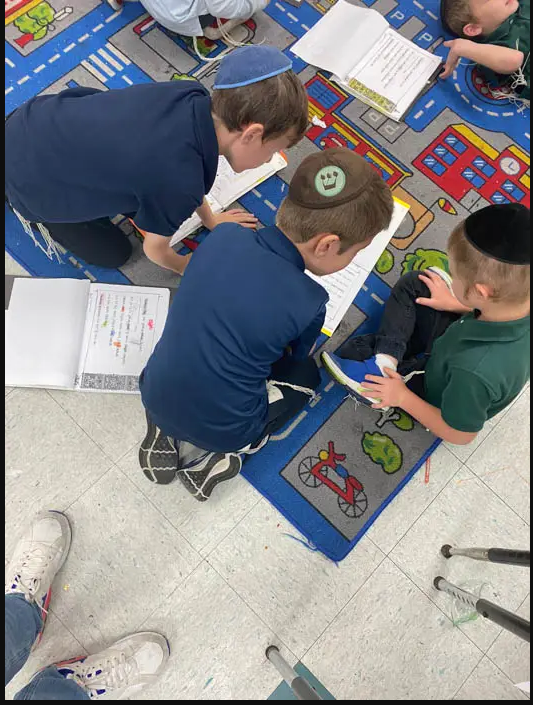

But one of the biggest benefits to the arrangement has been the opportunity for students at both schools to interact and bond. On Fridays, JEMS students join the Toras Chaim Toras Emes students at an assembly to end the week.

JEMS students join their umbrella school classmates from Toras Chaim Toras Emes, located across the street, for recess.

Girls from the umbrella school also visit and engage the JEMS girls in educational games and performances. Boys from Toras Chaim Toras Emes help put on Bible studies and play games and sports with the JEMS boys. JEMS students also participate in recess at the umbrella school’s playground.

Those interactions have enriched both groups, the JEMS founders say.

Jablon said she hopes getting the word out about what JEMS offers will encourage more parents to consider enrolling their children.

“In general, with parents of students of special needs, moving kids from one school to another creates a lot of instability. So, parents keep their children in programs even if they’re not that great.”

Jablon said the Miami-Dade County School District has been helpful by issuing timely individual education plans for students seeking to go JEMS so they can qualify for the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities.

JEMS already has opened a second classroom. The founders hope to expand the program at other Jewish day schools as the original students get older and need to attend single-gender classes as Orthodox Judaism requires. The founders also hope to be able to teach general life skills so the students can be as independent as possible as adults.

Says Jablon: “We want our kids to exist in the larger scheme of people and activities and potential jobs in any capacity they can muster.”

Isaac Wilbanks, left, and Joshua Akabosu are two of the original seven students who still attend Dickens Sanomi Academy in Plantation, Florida.

Joshua Akabosu was nearly hit by a truck when he was 10. He had run from school that day, as he often did. Announced to the class he was going home, then bolted through a door and into the neighboring streets.

School officials told Joshua’s mom, Juliet Sanomi, what she already knew: that they could no longer accommodate her son. He was a flight risk and posed a danger to himself and others.

Joshua, now 20, is on the autism spectrum. He has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. At the time of his accident, he was just learning to speak in complete sentences.

“I took him to (his district) school, they couldn’t handle him. I took him to private schools, same thing,” Juliet said. “And no fault to the schools. These children don’t come with manuals.”

But where does a single mother turn when she has nowhere else to go? When homeschooling is not an option because she is pregnant, and because she wants her son to interact with other children?

In Juliet’s case, she turned to herself. She started her own school.

Dickens Sanomi Academy in Plantation is celebrating its 10th year. It has 170 students, most of whom receive the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA), which is managed by Step Up For Students.

Joshua graduates this spring. He was one of the original seven students during the school’s first year.

“I am very grateful for the (FES-UA) because it was difficult. He wasn’t asked to be born with autism and it’s been a difficult road,” Juliet said. “I thank God for the scholarship because he’s done very well, the best he’s able to do, and that’s because we had the funds to do that.”

Joshua was the school’s first student. The second student came through a chance meeting with the mother of an autistic child. The mother was standing in the parking lot outside of a school. She was crying because school officials just told her the same thing Juliet had recently been told about Joshua.

To continue reading, click here.

Diana Diaz-Harrison and her son, Sammy

On this episode, senior writer Lisa Buie talks with Diana Diaz-Harrison, a former teacher, television journalist and founder at Arizona Autism Charter School in Phoenix, the Southwest region’s only tuition-free school specializing in best practices for students who are on the autism spectrum.

Diaz-Harrison started the school in 2014 after her son, Sammy, who was diagnosed with autism at age 2, began attending kindergarten. The arrangement wasn’t working well for Sammy and others who have ASD, she explains, noting that while federal law requires that exceptional students receive “free and appropriate” education in district schools, it’s no guarantee it will be the best education.

“I think that the stigma that is associated with an autism diagnosis, it's kind of fading … people don't think of it as a death sentence anymore. We are offering so much hope, along with other agencies in the community, that children with autism can learn. They can thrive.”

Sammy attended a private program for a couple of years, and while that was a better environment, the costs were not sustainable. Private programs can cost $40,000 to $50,000 per year.

So, she and other parents opened Arizona Autism Center with 90 students with the mission of using best practices such as applied behavior analysis. The school now serves 700 students on four campuses, including a high school and a virtual program. Another high school will open in Tucson this fall.

The founders’ efforts were rewarded last year when the school took the top $1 million award in the Yass Prize competition, which seeks to recognize and aid education programs that are “sustainable, transformational, outstanding and permissionless.”

In seeking to replicate its model, the school partnered with South Florida Autism Charter School in Miami-Dade County to start a National Autism Charter School Accelerator with the goal of getting at least one autism-focused charter in every state.

EPISODE DETAILS:

RELEVANT LINKS:

South Florida Autism Charter School

Autism and Applied Behavior Analysis

CDC Community Report on Autism

Justin Williams with his parents, Stacy and John Williams

OCOEE, Fla. – Justin Williams was 8 when he underwent surgery to allow more room for his brain to grow. For two months, he wore a halo brace and a plate on the roof of his mouth to push the bones in his face forward, one agonizing millimeter at a time.

At one point, Justin told his dad, John, that he’d rather die than live through that again.

“At the time, I was probably exaggerating,” Justin said, “but it was the worst eight weeks of my life.”

Justin, 18, was born with Apert syndrome, a rare condition where the joints in a baby’s head, face, feet, and hands close while in the womb. He’s undergone 15 surgeries. The first was when he was 9 months old. He learned to walk with both feet and hands in casts.

While Justin has endured some difficult moments in his life, he will be the last to say he’s had a difficult life.

“I’ve gone through a lot,” he said, “and it hasn’t affected me.”

Justin grew up on Ocoee, just a short walk from his family’s blueberry farm, where he helps direct the parking during picking season.

He graduated last spring from Foundation Academy in nearby Winter Garden. He attended the private Christian school since pre-K on a McKay Scholarship for Students with Disabilities (now the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, administered by Step Up For Students).

He begins classes at Valencia College this month.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: Tera Myers, a parent advocate for families of students with special needs and all who need more education options, is a consultant with the American Federation for Children.

Editor’s note: Tera Myers, a parent advocate for families of students with special needs and all who need more education options, is a consultant with the American Federation for Children.

Perhaps more than any other year, 2022 began with education on everyone’s mind.

January saw teacher’s union strikes at a time when students desperately needed schooling. March and April marked Development Disabilities Awareness Month and Autism Acceptance Month, with advocates highlighting inequities for some of the most vulnerable students. In May, news broke of just how devastating school closures over the last few years have been, especially for at-risk students.

As legislative sessions wind down and the end of the school year looms, this work cannot be limited to just a few months of recognition or a few days of controversy. Achieving a world where every student has the chance to succeed is not an easy or quick task – but the rewards are endless.

As a mother who fought for her child through the years, I experienced this process firsthand. My story began over a decade ago when I simply wanted my son to have a fulfilled life as part of his community; the traditional schools had no interest in helping meet that goal.

When our children were in school, they had different needs. Our oldest daughter attended private school thanks to a choice scholarship. Our youngest thrived in a virtual school. We were blessed that some educational options were working well.

But none of these options was right for Samuel, who was born with multiple disabilities and Down syndrome. While his diagnoses never defined him, they did limit his education options.

Our local public school was not motivated to educate Samuel. School officials seemed to think he would never be able to learn or do much in life. Making matters worse, he was being bullied, and there were no solutions coming from the school administration.

Virtual school was working for our daughter, but it was too rigorous for Samuel and did not provide the types of services he needed. I thought I had run out of options. I was discouraged and exhausted when I called school choice advocates in my state to see what else could be done.

They told me there was a chance – that the Legislature could pass a bill that would help my son and others like him.

After my family and others poured our heart and soul into years of lobbying for it, the state of Ohio passed the Jon Peterson Special Needs Scholarship. For students like Samuel, this was the missing piece. They were able to learn in an environment that worked for them and grow up to be thriving members of their communities.

We won our fight in Ohio, but the work continues for families like ours across the country. Leaders may take time to recognize students with disabilities one month or lament learning loss the next, but parents are watching to see if they will take the real steps our children need.

Education is the key that can unlock so many doors, and countless parents across the country are asking for nothing more than a chance at it for their children. When we look back at this school year, I hope that legislators and leaders across the country can say they did all they could to help every student succeed.

From its start in 1964 as “the little schoolhouse on the bayou," Bayou Academy in Cleveland, Mississippi, has changed location as its population grew. Today, the academy is home to more than 500 students and 70-plus faculty and staff members who strive to provide an excellent education in an environment that promotes rigorous academic challenges, Christian values, and student-engaged instruction.

Editor’s note: This first-person essay from Mississippi mother Leah Ferretti was adapted from the American Federation for Children’s Voices for Choice website.

When our son Thomas was about to move to first grade, his teacher told us he should repeat kindergarten. Being a teacher myself, and trusting the education system, I agreed without asking any questions.

But three weeks into Thomas’ second year of kindergarten, I told my husband that beyond Thomas’ speech difficulties, for which he was receiving services, something was not right. We decided to have him evaluated and learned he was struggling with severe dyslexia, attention deficit disorder, and anxiety.

We went to the school with this information and assumed Thomas would receive appropriate additional services and that everything would be fine. That was not the case.

School officials disagreed with the doctor’s recommendation that Thomas be taught using the Orton-Gillingham approach, arguing it was not what he needed. They said he would be fine, adding that Thomas was not the first dyslexic child they had enrolled.

I had not intended to continue my education after receiving my teacher certification, but to give Thomas a fighting chance, I returned and earned a master’s degree so I could help him myself. I asked the school district to let me come into Thomas’ classroom and be a provider during the school day so he wouldn’t have to spend so many hours on homework, but the administrators turned me down.

We had no choice but to begin doing our own research. That’s when we found Empower Mississippi, a grassroots movement that helps students with special needs and families like ours. Empower Mississippi puts people over divisive politics and works to give voice and hope, educating, engaging, and electing Mississippians dedicated to removing barriers to opportunity.

We learned about a state scholarship program for students with dyslexia, but soon found out access to it was limited. Then we learned that the Equal Opportunity for Students with Special Needs Act, enacted by the Mississippi Legislature during the 2015 legislative session, had created the Education Scholarship Program.

This education savings account program was designed to give parents of children with special needs the option of withdrawing their child from the public school system and receiving a designated amount of funds to help defray the cost of private school tuition and other allowable educational activities.

In the meantime, we found a local independent school, Bayou Academy. The teachers welcomed the help I was credentialed to provide to special needs children – and they welcomed Thomas as well. Even though we were still on the waiting list for the ESA, we moved Thomas to the academy.

A few months later, when I got the letter saying Thomas had been approved for the ESA, I cried and cried.

Eventually, our younger son, Henry, also was diagnosed with dyslexia. This time, we knew what to do. We applied for an ESA for him, he went on the waiting list, and was approved.

It was stunning to us that no one provides parents with information about these opportunities. We, like many families, had to find our own path. Because of that, it’s become our mission to help other families by sharing our story.

It’s been three years since Thomas transferred to Bayou Academy and he’s now at the point where he is successful in the classroom. He enjoys going to school and he has a host of friends.

Watching his smiling face, we are convinced that families should have the right to choose the best educational setting for their child. Income should not be a barrier. In any other sector, people have a choice. They also should be able to choose when it comes to their child’s education.

We are grateful to Empower Mississippi, the Education Scholarship Program, and Bayou Academy.

Carrie Brazer, pictured upper right with staff and students, has made it her life’s mission to find alternative treatments to heal the autistic child while heightening community awareness through her fundraising efforts with national and community organizations in support of autism research and awareness.

Editor’s note: Visit autismsocietyofthekeys.com for more information on the Carrie Brazer Center for Autism and cbc4autism.org for more on the Carrie Brazer School for Autism.

For 23 years, the Carrie Brazer Center for Autism in Miami has served students on the autism spectrum and others with neurodiverse conditions. During that time, Brazer, a Florida-certified special education teacher with a master’s degree in special education, noticed that families from the Florida Keys were driving as much as three hours to come to the area for therapies and other services.

To better serve those families, Brazer opened a small office in Tavernier, an unincorporated area in Key Largo with a population of 2,530. When a charter school campus across the street became available, Brazer seized the opportunity to open the school’s second campus on the half-acre lot.

The new campus opened last year with six large classrooms in a 5,000-square-foot building. The school has a large indoor play area with lots of swings. The weather usually is pleasant enough for the students to eat lunch outdoors.

“It’s just gorgeous,” Brazer said. “It’s very beachy and homey and airy and spacious.”

The center began small, with 10 students in its first class. Brazer’s goal is to expand that number to 100 when classes resume in August, keeping in mind the school’s goal to maintain a 5-to-1 student-teacher ratio.

In addition to classes for students with autism, the school also offers a separate program for siblings who are neurotypical.

“That way, parents don’t have to go to two different schools,” she said.

The addition of a new location for autism services came at a good time for the state. The COVID-19 pandemic caused delays in getting diagnoses and treatment by forcing providers to shut down in-person services and transition to telehealth appointments. Meanwhile, the state is proposing new rules that will make it more difficult for children to get therapies during the school day.

Brazer and her staff identify as a “positive discipline school,” one of the only in Florida for students on the autism spectrum. The Positive Discipline model, derived from the work of psychologists Alfred Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs, teaches children, teachers, staff and parents to be encouraging to each other and to themselves. It’s a school model designed to teach everyone to have a role that creates a sense of belonging and significance, with every relationship being nurturing and deeply respectful.

Brazer and her staff identify as a “positive discipline school,” one of the only in Florida for students on the autism spectrum. The Positive Discipline model, derived from the work of psychologists Alfred Adler and Rudolph Dreikurs, teaches children, teachers, staff and parents to be encouraging to each other and to themselves. It’s a school model designed to teach everyone to have a role that creates a sense of belonging and significance, with every relationship being nurturing and deeply respectful.

Programs include an intensive early intervention program for 2- to 5-year-olds, a full day school program for elementary, middle and high school students aged 5-22, and adult day training featuring life skills and vocational training for students over 21. Music therapy as well as community-based instruction that includes swimming and horseback riding are part of the curriculum.

And because part of the school’s philosophy is that there is a child inside of every individual, regardless of his or her age, students enjoy a playground built by the Miami Dolphins after Hurricane Irma.

To make the school accessible to more families, it accepts state scholarships, including the Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities, which beginning July 1 will include former McKay Scholarship students. The school also accepts all insurance so children can receive behavior therapy, allowing them to work closely with behavior assistants during or after school to improve life skills and reduce behavior problems.

Reflecting on the school’s first year of operation, Brazer counts building a strong community base among her successes. The school has partnered with the Autism Society of the Keys, a nonprofit organization that helps families with resources and hosts meetings and other events at the school.

Looking toward the summer, Brazer found it challenging to find field trip locations because of the lack of indoor venues in the Tavernier area, such as bowling alleys, skating rinks and bounce houses.

“Summer camp was a real test of what we’re up against,” she said. “We found a couple of good things that have pools and parks, aviaries and swim the with the dolphins.”

To attract more families, the school will host an open house in June. Parents will be able to tour classrooms and meet school staff while their children enjoy hot dogs and face painting.

“We really want to get the word out and let people know we’re here,” Brazer said.

LiFT Academy, presently located on two church sites in Seminole, Florida, aligns its programs and practices to a simple philosophy: to embrace a world where independence is possible for the neurodiverse.

Editor’s note: To learn more about LiFT Academy, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s earlier story here.

A Florida school specially equipped to teach students with neurodiversity – variations in the human brain associated with sociability, learning, mood and other mental functions – is expanding to help more children reach their potential and live independently as adults.

LiFT Academy, now housed on two tree-lined church campuses in Pinellas County on Florida’s Gulf Coast, recently bought a 60,000-square foot building in Clearwater that has been a YMCA for more than 50 years. The nonprofit school paid $3.8 million for the property that will allow it to quadruple its space.

The extra space will allow LiFT, which stands for Learning Independence for Tomorrow, to serve 350 to 400 students over the next three to four years. The school now serves 150 students, about 90% of whom receive financial aid in the form of state scholarships, including several managed by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

“Since LiFT was founded in 2013, we’ve been renting space from the church,” the school’s executive director, Shawn Naugle said. “We’ve grown over 600 percent in nine years; we’ve quickly outgrown our space.”

Among the three programs LiFT offers is one focused on providing instruction for students in grades K-12. Another is a four-year post-secondary transition program for students who have left high school but desire continued academics, career readiness and life skill training. The school also offers an adult day program that provides continued learning and employment skills while promoting social enterprise.

School leaders had been looking for a larger property that they could own rather than rent. Initial conversations with the Clearwater YMCA proceeded favorably over the summer, and the deal closed Dec. 22.

The school was able to buy the property with help from a combination of fundraisers and grants, as well as donations from the community, Naugle said. LiFT is expected to launch a capital campaign during the next few months to raise money for building renovations.

Leaders hope to open the new campus in the fall, but Naugle said it could take until early 2023.

“We’re staying flexible and positive and hopeful,” he said.

Beyond accepting more students, the expansion will add jobs for teachers and support staff. It also will allow the school to open an in-person family resource center, which now is virtual, offering access to 70 partners ranging from therapists, counselors, and specialists.

Additionally, the school wants to provide space to groups that offer enrichment, after-school and sports programs as well as lease space during non-school hours to various community groups.

“We want to be a resource to the community,” Nagle said. “We want to help as many people as we can.”

LiFT has come a long way since it opened with 17 students and five unpaid teachers. It began as the vision of two moms, Kim Kuruzovich and Keli Mondello, who, inspired by their daughters, set out to create an inclusive and accepting environment where children with autism, ADHD, and other special needs would be free from bullying and have the peace to learn and grow.

Last year, LiFT joined 30 other Florida schools in adopting a content-rich English language arts curriculum called Wit and Wisdom, which rolls history, art, science and other subjects into reading, writing, speaking and listening.

“It’s important for our students to have that same level of challenging academics as other students,” Naugle said when the program launched. “We want our students to have the best, because they deserve the best.”

STARS Autism School in Miami aims to prepare students to become as independent as possible, offering enrichment programs such as robotics, chess, yoga, music, art, dance and sports in addition to academics.

Editor’s note: This first-person essay from Florida mother Stephanie Rodriguez was adapted from the American Federation for Children’s Voices for Choice website.

Stephanie Rodriguez

I have three children. My younger two, Giana and Javier, have autism. I am thankful for the scholarship my children received to attend STARS Autism School.

Before STARS, Giana was in a traditional district school. She was isolated in a corner and living in timeout because the teachers didn’t understand her. We ultimately were asked to leave because the school didn’t know how to handle her special needs.

Giana was nonverbal when she arrived at STARS. Now, two years later, she speaks in full sentences. She knows her colors, her numbers, and can distinguish animals. But best of all, she can express her wants and needs.

She sometimes needs to be told to stop talking.

STARS staff members are intentional about everything. When you walk into the school, you smell calming essential oils. There are many windows to let in natural light. And it’s a one-stop shop. I used to have to leave work early to take Giana to occupational and speech therapy, but she gets everything she needs at her school.

When my daughter is having a bad day, the staff knows how to work with her to get her back on track. She feels loved. And she has friends. We have play dates, which is a big deal.

There was a time when we couldn’t go to restaurants because of Giana’s meltdowns. Now, we can sit and have a meal as a family.

I have hope for my son, who was recently diagnosed with autism. My hope is that STARS will help him as it has helped Giana.

Just because my children have a special need doesn’t mean they deserve less than other students. Thanks to Florida’s choice scholarship programs, they are getting the opportunities they need to be all they can be.

Gretchen Stewart focused her dissertation on research that would inform the model for Smart Moves Academy, involving more than 40 experts in brain development, learning, cognition and movement in her quest to assist children with autism. The new school is set to open in 2022.

"There was one event that triggered me to create the private school I had always thought about over my career. It came one day when my son came home and said to me, 'Mom, I’m a weird kid.' That broke me, and for a time, it broke him too. " – Gretchen Stewart

Gretchen Stewart is the founder of Smart Moves Academy, an inclusive private school launching in the Tampa Bay area with a vision to ignite the mind through movement. The school’s model will optimize brain performance through physical activity for lifelong learning, health, fitness, and emotional well-being. Stewart has been named a Drexel Fellow and received a grant from the national non-profit foundation to further develop her plan and open the school in 2022. The school will accept scholarships administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. Answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Gretchen Stewart

Q. You received your undergraduate degree in political science, government and Spanish at the University of Minnesota - Twin Cities. What were you planning to do at that time and what prompted you to pursue education instead?

A: I dropped out of high school at age 16. Looking back with the understandings I have now, I was at risk for school failure from the start of my school career as a kindergartner. My family background included many risk factors associated with school failure, and the city I lived in had de-facto segregated schools, low expectations for racial minorities, and in general, a profile of low achievement for children from low-income families.

When I finally understood that education could mean a way forward out of those circumstances, I wanted to try to go to college. At age 21, I earned an adult high school diploma and conditional entrance into a university. Being a conditional student meant I had to make up coursework to prove I could make it academically at the college level. During that time, I worked two jobs, one washing dishes in the cafeteria at my residence hall, and the other at the law school, as a mock client for the grad students to practice client intakes with.

It was here that I gained an interest in the work of an attorney and decided to take classes to prepare me for law school. I was all set, until life stepped in and changed my plans. I was close to graduation when I was in a bad automobile accident. I had to quit my job and move off campus in order to focus on recovery. It was incredible that I was able to finish my senior year and graduate. In the process, however, I had to let preparing for the law school entrance exam fall to the wayside.

As I thought about what to do next, a good friend told me she never really saw me as a lawyer, but instead thought I’d make a great teacher. She handed me a green piece of paper with instructions on how to apply to a graduate program that would pay half of the cost for a master’s degree, train me to be a teacher, get me licensed, and guarantee a teaching job in Minneapolis Public Schools for at least five years. I consulted my family and friends, and to my surprise, everyone agreed that they had always felt education was a good fit for me.

I had never considered it, mainly because of my early struggles in school, but somehow, the universe took over and pointed me toward teaching. I was extremely lucky to be accepted to the Collaborative Urban Educator program at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, right out of college. The CUE program was an intensive year of teacher preparation that led to full licensure and my first job teaching fifth grade at an urban, art-infused public elementary school. In my third year of teaching, I became the first ever probationary teacher to reach Elementary Teacher of the Year finalist.

I found that I loved teaching; I excelled at it, and I was driven and inspired by working with children who were my age when I started to fall through the cracks of school. I was very focused on doing everything I could to prevent a single student of mine from experiencing school failure. My classroom became known for being a creative, fun, and rigorous environment where everyone could excel.

For myself, I developed a new sense about what it means to be a valuable contributor to something greater than myself. There is no satisfaction for me like that which comes from a hardworking parent who is grateful to you for guiding their child to success in school after ongoing struggles with learning, achievement, and social relationships.

Q. You have extensive experience in educating students with learning differences. What influenced you to go in that direction? Also, please tell us about the nonprofit organization you founded, Top of the Spectrum.

A: Harkening back to my first teaching job at the arts school, we had a regional classroom at our school for students with the most severe behaviors in the district. I would walk by that classroom and try to peek in. I would wonder about the students and the teachers, whom I rarely saw and who seemed to be a bit separate from everything else. That separation bothered me in many ways.

So, I began to befriend the teacher and the aides in the classroom. I started asking questions to learn more, and we became friends. One day, the teacher of that classroom asked me if would consider having one of her students come to my class for reading instruction. I was thrilled and gave an emphatic yes. I was so excited to see if I could work successfully with a child who was labeled with the most intensive of special needs. I’ll never forget that young man and our time together with him in my classroom. He became a model student in reading and was able to mentor younger readers. His success was hard earned, and his reputation changed, and he felt a part of our class.

The power of inclusion and belonging is incredible in terms of it being a catalyst for community and achievement. Everyone benefited from him being in our class. So, I became drawn to the idea of inclusion and its impact on learning. I also wanted to learn as much as I could about the root cause of learning differences and behavioral challenges. I went back to school and gained a second master’s degree this in Special Education. I then earned teacher certified in K-12 Learning and Behavioral Disabilities and began teaching as a special education teacher.

Shifting gears, On Top of the Spectrum is a non-profit organization in Tampa with the mission of expanding inclusive opportunities for young people. At age 3 my son was labeled with autism and other developmental differences. My life with him and the son that I later adopted who has Down Syndrome, as well as my school experience, has inspired me to work to create more inclusive communities.

I found as a parent that it was no simple task to do what comes simply to many others, like enrolling my kid in a karate class. Most of the time, the instructors are not knowledgeable on how to adapt to include kids who don’t respond to a single method of teaching. That means having to leave our community to search for any place that is accepting and prepared to engage a child who simply wants to be included and have fun learning for example, karate. Many times, those places do not exist, and it’s difficult to explain that to a child. So, we set about to change that and help prepare people to welcome anyone who comes through their doors as an opportunity to build stronger communities.

We created On Top of the Spectrum to focus on health and fitness because as children with special needs leave the school system as young adults, there is very little opportunity for them to be included in activities that nurture lifelong health and fitness. We work with gyms and personal trainers to enable them to train a wider range of people effectively, including people with autism. We also strive to increase access to outdoor adventures that have a physical element for people with developmental differences. In 2023 we are taking a diverse, inclusive group of young people to Tanzania to climb Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest free-standing mountain in the world. Some of our participants have been training for the past two years to be able to accomplish such an incredible personal challenge, all the while improving their personal health and fitness, inspiring the gyms they train at, and being fully included in the communities they train within.

Q. Tell me about your first experience teaching. How did it influence your career later? After years working in district schools, what influenced your decision to go out on your own?

A. My first teaching experience was in a unique public school in the heart of Minneapolis. Our students spoke 35 different languages and most lived at or below the poverty line. The school was art infused, meaning our students had access to curriculum and activities that were arts focused. For instance, I spent a few years working in collaboration with a professional dancer to create math curriculum that was taught through dance. This was important for our students because we faced a very real language barrier when trying to teach mathematics in English to students who did not speak English.

I was very fortunate to have had a wonderful principal in my first years of teaching that invited us as professionals to experiment to find what really worked in terms of individual student progress. I believe I had the very best possible start to my teaching career that I could have had. As I gained teaching experience and shifted from general education to special education, I expanded my teaching certifications to include more age ranges and subject matter, taught from kindergarten to high school, taught in a charter school, served as an assistant principal, and then went on the to the state department of education in a technical assistance role.

After that, I became an executive director of curriculum and instruction pre-K through 12 in a district serving about 25,000 students and families. Throughout my career, my focus remained singular in terms of my philosophy that innovative, inclusive education is the driver of the type of change in our world that I want to see. I want to see a world in which we don’t have to orchestrate inclusion, because it occurs naturally. This is important because the development of intellect depends on feeling and being safe to take academic risks within a supportive learning community.

In going out on my own to create something new, there are many reasons that I felt like I could not get change I wanted to see in education to occur on a large scale. I am a product and champion of public education, not so much as it is, but as it has the potential to be. As a parent of school aged children, I struggled with the lack of a meaningful education my children experienced in public school.

There was one event that triggered me to create the private school I had always thought about over my career. It came one day when my son came home and said to me, “Mom, I’m a weird kid.” That broke me, and for a time, it broke him too. He no longer wanted to go to school. I could no longer escape that this is not what should be happening in schools for children, and that we simply cannot keep doing things in ways that result in any child feeling like they don’t have a safe place of belonging in which to grow academically and socially. There were other issues that tipped the scale for me too, like the persistent achievement gaps in schools between differing racial and socioeconomic groups of kids, the loss of excellent teachers due to systemic wrongs, and archaic, sedentary systems of instruction.

Q. Congratulations on receiving support from the Drexel Fund. How did you learn about the organization and how is it helping you embark on this new adventure?

A. I am still in awe that I was one of just three chosen from among more than 250 applicants to become a Drexel School fellow this year. I learned about the Drexel Fund by googling, “grants for private school start up.” I came across them in 2019 and attended an informational meeting that was held at Step Up for Students. After I attended that meeting, Drexel reached out to me and let me know they had an interest in helping me launch my school.

So, while completing my Ph.D. at the University of South Florida, I started taking some early steps to prepare myself to be a competitive candidate. I worked on establishing the non-profit for the school, getting some professional development in the brain and learning, visiting other models, and having conversations about school start up with experienced people. For me, the fellows program allows me to work full-time on launching Smart Moves Academy.

Drexel helps seed private schools like mine by providing individualized resources to help fellows launch successful schools. As a fellow I get access to other school entrepreneurs that have been running high performing and successful private schools, executive coaching, and workshops to help me prepare a sustainable business plan. It’s wonderful to be surrounded by inspirational and visionary people who are doing the same work that I am.

Q. What type of research did you participate in at the University of South Florida and how it did help you develop this model?

A. At USF I focused my dissertation on research that would inform the model for Smart Moves Academy. My research involved more than 40 experts in brain development, learning, cognition and movement. The group was selected because of the members’ knowledge in the practical application of teaching strategies that embrace physical movement as a lever to optimize the brain in positive ways that impact learning. The results of my mixed methods study revealed a set of 27 elements that the experts felt should be present in an inclusive school where movement is a central part of how all students maximize their potential.

For me as a parent and as an educator, the most exciting of these strategies coming to life at Smart Moves Academy include daily neurodevelopmental movement, more rather than less recess, outdoor learning, and hands-on, active academics that align well with what we know about how the brain learns. When you combine these approaches inside of a well-designed and supported inclusive environment, you get our school.

Q. There are many schools that specialize in helping students on the autism spectrum. What will set Smart Moves Academy apart from the others?

A. Smart Moves Academy pairs engaging, rigorous academics with continuous development of the biological foundations critical to learning and social emotional well-being. We do this through movement. There is no other inclusive school in the United States that does this. For students that come to us with a label of autism, we can’t help but be very excited.

The research base of our neurodevelopmental approach is stunning when it comes to helping students with autism reach their potential and open doors to goals that may have been unreachable in the past. The inclusive model at Smart Moves Academy cannot be understated in terms of supporting a student with autism. Our school environment creates an authentic sense of belonging and safety for each student, thereby growing the self-confidence and perseverance needed for deep intellectual and character growth, as well as the formation of lasting friendships.