The following bill has been filed for the 2022 Florida legislative session, which begins Jan. 11 and runs through March 11.

BILL NO: SB 1294

TITLE: Individual Education Plan Meetings

SPONSOR: Sen. Joe Gruters, R – Sarasota

WHAT IT WOULD DO: It would add to ss. 1002.20 and 1014.04, F.S. the right for parents of public school students who receive individual education plans (“IEPs”) to audio or video record any meeting with their child’s IEP team, provided they give the school district written notice of their intent to do so at least 24 hours in advance of the meeting. These rights would still be subject to the protections provided in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (20 U.S.C. a. 1232g) and ss. 1002.22 and 1002.225, F.S.

For more information, click here.

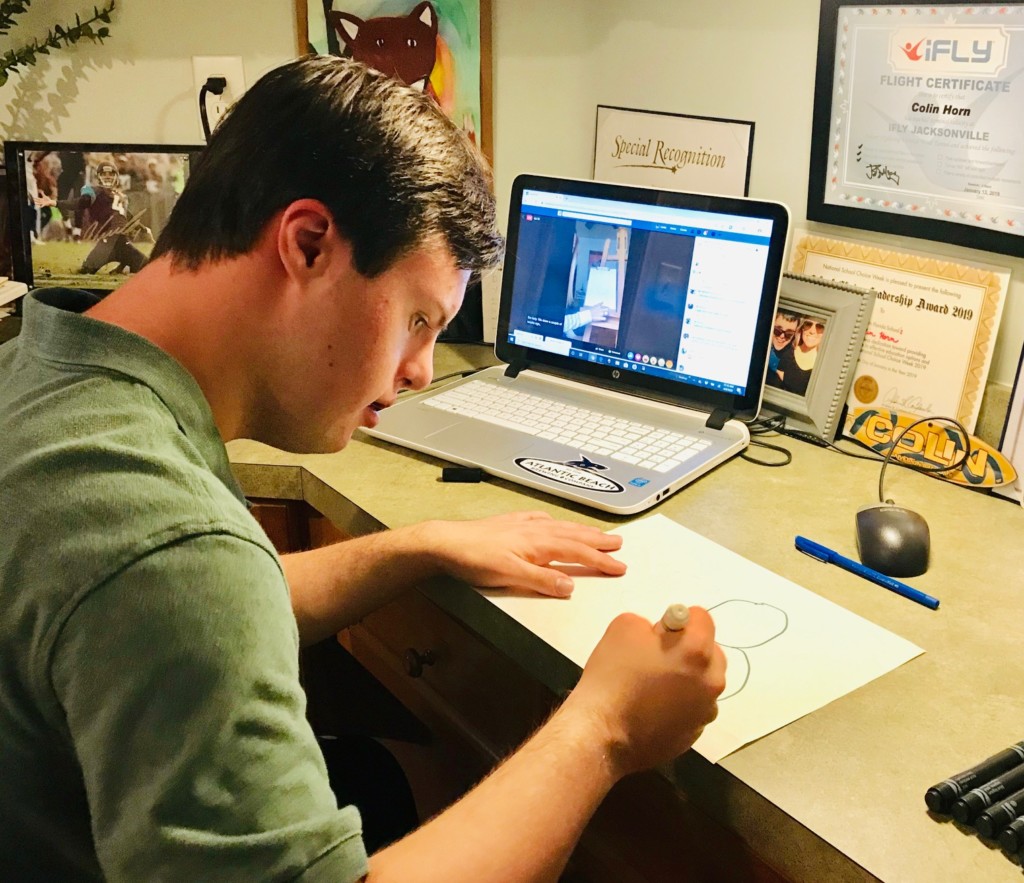

NFSSE student Colin Horn, 18, draws with his art teacher via Facebook Live.

Like most schools that were shuttered by the COVID-19 virus, North Florida School of Special Education in Jacksonville had to sprint to set up a distance learning program for students suddenly confined to their homes.

For Sally Hazelip, the head of NFSSE, it was a longer race that taught her how to navigate unfamiliar education territory.

“I just ran a marathon in October, and your mental strength in a marathon is almost as important as your physical strength, she said. “That’s what this is like now: Just put one foot in front of the other and push through it.”

While adapting on the fly to the virtual classroom has been disruptive to educators, students and parents in public and private schools, the transition has been particularly challenging to NFSSE. It has 250 students with intellectual and developmental differences, such as Down syndrome, autism, fetal alcohol syndrome, and traumatic brain injury. Most are between the ages of 6 and 22 (including 26 students on the Gardiner Scholarship, which is administered by Step Up For Students, the host of this blog), while 65 post-graduates ages 22 and up receive vocational training in micro-enterprises.

Switching them to online lessons overnight yanked everyone out of their comfort zones.

“The fear of the unknown can sometimes be daunting,” Hazelip said, “but my staff has risen to the occasion in so many unique ways.”

Parents also wondered how they would handle the additional responsibilities.

For Linda Horn, whose son Colin, 18, has Down syndrome, the change forced her to recall her days homeschooling her child when the family lived in Seattle.

“I had to personally change my mindset – I had to accept it,” Horn said. “I had to be a better mother and teacher for Colin. I had to be the adult in room. I needed to show Colin everything was calm and routine.”

Christian Roberts, 17, attends class at his new desk – his family’s dining room table.

Cathy Roberts suddenly had three children learning at home: Christian, 17, who has Down syndrome and attends NFSSE; a 16-year-old son with ADHD who attends another private school for students with learning differences; and a 17-year-old daughter who is typical and attends a Catholic school.

“Structure for our kids is key,” Roberts said. “I had to sit down with Christian and explain the virus to him. Initially he was upset. He wanted to go to school. I put up a calendar so he can go to it every day and see his schedule. I have had to become more structured. It’s been a change for all of us.”

Thankfully, several online curricula – Unique Learning Learning System, i-Ready, TouchMath – already were being employed on Smartboards in NFSSE classrooms, so teachers and students were familiar with them. That helped facilitate the academic side of the equation.

What sets NFSSE apart from other schools, though, is what happens outside the classroom.

The school offers several unique hands-on learning opportunities that stimulate intellectual and emotional development and prepare students for independent living. These include Berry Good Farms, an urban organic farm that grows fruits, vegetables and herbs; a culinary arts program where students prepare what the farm grows; therapeutic and recreational horseback riding; and cross-fit training. The school operates a food truck that goes out regularly into the community. Its Barkin’ Biscuits program uses fresh ingredients from the farm to make dog biscuits sold on the retail market.

NFSSE also has reverse-inclusion clubs in which typical students from outside the school participate in extracurricular activities and vocational training programs. And in January, the school opened its crown jewel, a $10 million state-of-the-art campus expansion whose amenities include a fine-arts center, individual rooms for sensory, physical, speech and occupational therapies, and a physical education complex with a gym and locker rooms.

“Academics are incredibly important,” Hazelip said, “but those hands-on activities take them to a different place and keep them engaged.”

Now those activities are on hold, awaiting the all-clear signal to return on the public health front. With it goes a huge part of what makes NFSSE special – elements that are difficult, if not impossible, to replicate remotely.

It’s like limiting Superman to one superpower. The school and its families have been up to the challenge, though.

“I think families with kids with special needs are really resilient,” said Hazelip, whose son Collin, 25, has Down syndrome and is a graduate of NFSSE. “There are so many unknowns. You don’t ever feel like you have all the answers. Part of it is just taking things one day at a time, and to look for creative ways of connecting with your child.”

From the start, teachers have been in close contact with parents and students every step of the way. The school has supplied laptops to families who lacked them. They are using Zoom to conduct live, interactive lessons in core subjects. Students submit assignments at their own pace.

“Zoom has been a godsend,” Roberts said.

Resource teachers use Facebook Live and the school’s private YouTube channel to hold daily art, music, PE, gardening and yoga classes, as well as story time. Berry Good Farms teachers post video cooking classes for students to follow. The equine teacher shot a video showing how she feeds the horses.

On April 3, the school even held its monthly scheduled student and faculty assembly, only this one was recorded in advance and posted online. It included special guest Josh Lambo, place-kicker for the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars, who read the Dr. Seuss book “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” Over 150 people watched it live.

Virtual learning is not the same as being out in the greenhouse or the stables, but it maintains the connection between teacher and student, and keeps the kids on a routine that for many is vital to their intellectual and emotional development.

“North Florida prepared [Christian] well for this,” Roberts said. “They already do a lot of work on computers, that part was easy for him. He has such a tight-knit bond with his teachers, being able to see them every day has made a difference.”

Linda Horn has tried to fill the additional time at home with Colin with life skills as he prepares to enter the school’s transition program next year.

“Independent living skills are important,” she said. “So we work on doing the laundry, cooking skills, getting lunch ready and working on dinner.”

She and her son also try to get out in the community as much as possible in the era of the coronavirus.

“I make it a point to stop and say, ‘Look at the plants here’,” she said. “I really try to incorporate what he’s learned. We’re going to go to Lowe’s and buy a tree and plant on Earth Day.”

Hazelip says this unplanned journey into distance learning can be characterized by two words: “resiliency” and “connection.”

“The biggest positive out of this ordeal is we’re one big family,” she said. “That support has given them strength to get through this.”

Kim Kuruzovich, an educator with more than 20 years experience in public, private and home schools, is executive director of LiFT Academy, a private school for students with special needs. Of 130 students, 124 attend with help from state-supported school choice scholarships.

SEMINOLE, Fla. – Kim Kuruzovich’s daughter Gina has moderate autism, speech apraxia and dyslexic tendencies. She began a suite of therapies at age 2, then, at age 4, saw a psychologist for an educational evaluation.

The expert wasn’t encouraging.

“He told us, ‘You can look forward to Gina putting pencils in a box,’ ” recalled Kuruzovich, who has more than 20 years of experience teaching students with disabilities.

She and husband Mike drove home in stunned silence. It took a couple of months, but they snapped out of the haze and chose to ignore that doctor. It was the start of Kuruzovich learning to trust her instincts as a parent as much as she trusted her instincts as an educator.

Now, 19 years later, Kuruzovich is executive director of a private school built on those instincts.

LiFT, which stands for Learning Independence for Tomorrow, opened in 2013 with 17 students and five unpaid teachers who wore every hat imaginable. Today, it operates on two spacious, tree-lined church campuses. They serve more than 130 students with special needs, 124 of whom attend thanks to state-supported school choice scholarships.

“I never, ever wanted to go into administration. Ever,” Kuruzovich said. “I only ever wanted to be a teacher. I love teaching. I love seeing the kid get it and feel good about themselves.”

“What I found is I still get it as an administrator, but I get it in a bigger way. Now it’s not just my classroom, it’s every kid in this school.”

Before LiFT, Kuruzovich had taught in public, private and home schools. Her passion and talents helped make LiFT possible.

So did school choice.

Three state-supported scholarships - the McKay Scholarship, a voucher for students with disabilities; the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism; and the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income and working-class students - allow many LiFT parents to access a school they wouldn’t have been able to afford otherwise. (The Gardiner and FTC scholarships are administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.) But those scholarships also opened doors for Kuruzovich and her colleagues. It gave them power to create a school that could best serve those parents – and sync with their own visions of what a school should be.

In Florida, where school choice is becoming mainstream, more and more educators like Kuruzovich are walking through those doors.

***

It’s the first week of the school year, and Kuruzovich is in peak form – gliding through hallways and classrooms, a fast-talking, wise-cracking, blond blur of smiles and warmth.

The sheer number of inside jokes she shares with her students highlights how deep her connection runs with each of them. (more…)

Brandon sat quietly in his wheelchair but grew increasingly agitated as his lawyer, Clint Bolick, answered rapid-fire questions from an aggressive reporter.

His mother, Donna Berman, stood behind him, worrying he might erupt into a fit, or worse, a seizure.

Brandon’s service dog Cody even sensed the frustration and made a noise in defense of his best friend.

“Can we get him out of here?,” Brandon muttered about the reporter.

Another reporter noticed his agitation. "We've been trying to get rid of him for years," he quipped.

Brandon, who had autism, smiled and kept his composure.

Brandon was 16 at the time. He and his mom had come to Tallahassee to attend a hearing for Faase v. Scott. Florida's statewide teachers union filed the case to halt a 2014 law that expanded the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and created the Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts (PLSA), a scholarship program for children with special needs.

After years of struggles in public and private schools, Brandon and his mom felt the new program finally offered a path to an education that would work for him. They, along with other parents and students, jumped into the lawsuit to come to its defense.

Lawyers for the teacher unions claimed tax credit scholarships were their primary target. Brandon and other children using PLSAs were simply “collateral damage.” The two programs were linked in a sweeping piece of legislation the union argued violated the state constitution.

Brandon, his fellow intervenors, and the state's lawyers ultimately prevailed.

Their win set the stage for a series of other legal victories for Florida's school choice programs. The infant program they helped defend has blossomed into the nation's largest education savings account program. It's now called the Gardiner Scholarship, and it supports more than 10,000 students with special needs. (more…)

by Allison Hertog

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings - they have the same parents but are often rivals - vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings - they have the same parents but are often rivals - vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

In most states, charter schools have the option of freeing themselves from these and other disputes by essentially becoming their own districts (legally termed Local Education Agencies or “LEAs”). But the vast majority of charters, even in states like California, where they have the option of becoming their own LEAs, have not taken on the responsibility of fully controlling their own special education programs – possibly out of fear, ignorance or politics. Fortunately, many of the more competent and high-achieving California charters - like KIPP, Aspire, and Rocketship - have chosen the path of autonomy and accountability and are leaving behind special education disputes with districts.

Where I work in Florida, where essentially charter schools don’t have the option of becoming their own LEAs (as is also the case in places like Virginia, Maryland and Kansas, and in New York for special education purposes), these special education disputes are problematic for many reasons. They’re terribly inefficient; they come at the expense of children; and they fly in the face of the charter school movement’s supposed commitment to autonomy and accountability.

To illustrate why it makes sense that some of the most competent charters are choosing to become their own LEAs and take full responsibility for special education, I’m going to use a business analogy that doesn’t carry the emotional baggage of disabled children.

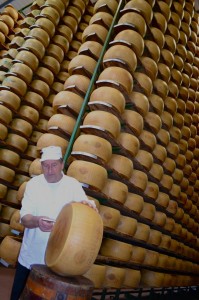

Imagine a young entrepreneur who runs a new and successful Italian restaurant called “Vagare.” Vagare (i.e., the charter school in this story) has grown to serve roughly 300 customers a day. But in this city there’s a local corporate giant: “The Italian Restaurant Company” (i.e., the district). Founded in the late 1800’s, the IRC has virtually cornered the market on Italian restaurants. It serves thousands of customers daily, owns hundreds of locations, and controls restaurant supply firms and food supply chains. You get the picture.

The IRC has contracted out some of its locations and provides certain supplies to Vagare and other smaller restaurants. Vagare locally sources most of its ingredients except for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, which, by contract, it is required to obtain from the IRC, which buys it in bulk from Italy. (more…)

Should charter schools be required to educate an identical proportion of special needs students as public schools? Should charters be required to follow the same rules governing special needs students as public schools?

Last month the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights released a memo that said yes to these questions. Education Next reached out to three education experts – Robin Lake, Gary Miron and Pedro Noguera – to get their take on the issue.

Lake

Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothel, says charters should not “counsel out” special needs students by recommending they attend other schools, but she opposes new regulations or enrollment quotas.

Lake recognizes that some charter schools specialize in special education while others focus on different academic pursuits. As a result, some charters serve only special needs students and others serve none at all. The same is true for public schools, she says, and that means a quota system would result in forcing kids out of schools that may work well for them just to achieve a proportional balance.

Lake says cities should focus on resources, not quotas. She concludes:

“Cities need to stop talking about what’s the ‘fair share’ through the lens of a charter or a district, consider instead what students need, and leverage the right combination of resources to meet that need.” (more…)

After 13 years teaching in the public school district, Merili Wyatte went to work for a private school. It was a chance to spend more time with her son and daughter, who attend the school. And to work in an environment where her religion was part of the curriculum.

This is the second story in an occasional series that looks at teachers and school choice. Read our first story here.

For years, Merili Wyatte was a special needs pre-kindergarten teacher at a perpetually A-rated traditional public school in Tampa, Fla. She loved the Title I school, her coworkers and her students. “My experience in public school was really good,’’ she said.

But the Seventh-Day Adventist and her husband sent their two children to Tampa Adventist Academy, a 155-student private school with prekindergarten through the 11th grade where Jesus is a big part of the daily lesson.

“I wanted my kids to be surrounded by that … kind of like a filter,’’ Wyatte said.

One day, she found herself longing for that same environment.

One day, she found herself longing for that same environment.

Bring up school choice, and most people focus on what it means to parents and students. But as the school choice movement continues to grow, teachers are searching for options that work better for them, too.

Nationally, there are 602,900 private school teachers, 3.2 million district school teachers and 72,000 charter school teachers, according to the most recent figures available. There aren’t statistics, though, that track whether teachers leave public schools for private school, or explain why educators choose a charter or virtual school over a traditional one.

Anecdotal evidence points to a variety of reasons, from a desire for better pay or hours, to an opportunity to try something new or, as in Wyatte’s case, to follow personal convictions and be closer to her children.

Wyatte has a bachelor’s degree from the University of South Florida in specific learning disabilities and is half way to a master’s. After 13 years in the system, she left the Hillsborough County school district three years ago to teach kindergarten at Tampa Adventist. There she can interact with her son, 8, on the playground or at lunch, and keep an eye on her 15-year-old daughter.

“There’s a boy she likes,’’ Wyatte said. “I like that I can look out my door – and they know I’m looking.’’ (more…)

Pension ruling. In a case brought by the state teachers union, the Florida Supreme Court rules 4-3 that it is constitutional for the state to require teachers and other state workers to contribute 3 percent of their pay towards their pensions. Coverage from the Herald/Times Capital Bureau, Palm Beach Post, Lakeland Ledger, Orlando Sentinel, Daytona Beach News Journal, Tallahassee Democrat, Associated Press. StateImpact Florida considers potential impacts on the lawsuit against SB 736.

Pension ruling. In a case brought by the state teachers union, the Florida Supreme Court rules 4-3 that it is constitutional for the state to require teachers and other state workers to contribute 3 percent of their pay towards their pensions. Coverage from the Herald/Times Capital Bureau, Palm Beach Post, Lakeland Ledger, Orlando Sentinel, Daytona Beach News Journal, Tallahassee Democrat, Associated Press. StateImpact Florida considers potential impacts on the lawsuit against SB 736.

Teachers in Palm Beach and Broward are “devastated,” reports the South Florida Sun Sentinel. “Bitter disappointment,” writes the Tampa Tribune. “Dashed hopes,” writes the Gainesville Sun. The state should offer modest raises to “lessen the sting,” editorializes the Tampa Bay Times. Gov. Rick Scott should convert the savings into better teacher pay, editorializes the Palm Beach Post.

School safety. Gov. Scott will “listen to ideas” but not push for gun law changes, reports SchoolZone. Some Pinellas schools will consider “buzz-in access,” reports the Tampa Bay Times. Officials in the Hernando district are quietly dropping the issue, the Times also reports. The Palm Beach County district will spend $400,000 on school police aides, with more expenses on the way, reports the Palm Beach Post. Escambia Superintendent Malcolm Thomas wants armed, plainclothes marshals, reports the Pensacola News Journal.

Charter schools. The Clay County School Board shoots down an application for a performing arts academy. Florida Times Union.

Test score limbo followup. State Sen. John Legg says fix the problem with concordant scores, pronto. Tampa Bay Times.

Teacher evals. Pasco officials say in response to a query from Patricia Levesque at the Foundation for Florida’s Future that the district isn’t ready for the new requirements, given the need to develop hundreds of new tests, reports the Tampa Bay Times. (more…)

“Teacher bashing” and Newtown. Tampa Bay Times columnist Bill Maxwell sees a connection.

Advanced Placement. Is Florida's approach worth it? asks the Miami Herald. (Here's another stat worth considering: The number of passed AP tests in Florida has climbed from 87,852 to 136,265 – an increase of 55 percent - over the last five years alone.)

High school grades rise. But with changes in the formula, comparisons to past years are dicey. Miami Herald. South Florida Sun Sentinel. Palm Beach Post. Orlando Sentinel. Florida Times Union. Lakeland Ledger. Fort Myers News Press. Naples Daily News. Florida Today. Pensacola News Journal. Gainesville Sun. Tampa Bay Times. State Impact Florida.

High school grades rise. But with changes in the formula, comparisons to past years are dicey. Miami Herald. South Florida Sun Sentinel. Palm Beach Post. Orlando Sentinel. Florida Times Union. Lakeland Ledger. Fort Myers News Press. Naples Daily News. Florida Today. Pensacola News Journal. Gainesville Sun. Tampa Bay Times. State Impact Florida.

“Special education crisis.” That’s the term Tampa Bay Times columnist Sue Carlton uses to describe what’s happening in the Hillsborough school district.

More school security. State Rep. Mike Fasano, R-New Port Richey, wants more school resource officers in the wake of Newtown, reports the Tampa Bay Times. Similar talk in South Florida, reports the Sun Sentinel, and on the Space Coast, reports Florida Today. Absenteeism spikes Friday, the Times also reports. The Palm Beach Post takes a look at charter schools’ response to the tragedy. Don’t turn schools into forts, writes Orlando Sentinel columnist Beth Kassab.