Editor’s note: redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips wrote this analysis on school reopenings amid the coronavirus pandemic for The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

Editor’s note: redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips wrote this analysis on school reopenings amid the coronavirus pandemic for The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

Fifty of the nation’s 120 largest school districts remain fully closed as of mid-October 2020, according to the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity’s latest review. This is an improvement from August, when 71 of these districts were closed. Altogether, currently closed school districts serve 5.2 million children, including an estimated 1.15 million children living in poverty.

Many of the closed school districts have no current timeline for reopening in-person learning. Several of these large school districts — such as Albuquerque, N.M., Howard County, Md., Long Beach Unified, Calif., and Cumberland County, N.C. — have announced that schools will be closed through December.

At least eight of these school districts have no announced or proposed timeline for returning to in-person learning. Table 1 provides an overview of the current operating status and school enrollment of the top 120 school districts.

To view the chart and to continue reading, click here.

The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on Aug. 6 held a public hearing on “Challenges to Safely Reopening American Schools,” featuring former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan; Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Broward County (Florida) Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie; and Angela Skillings, a second-grade teacher in the Hayden-Winkelman Unified School District in Arizona. You can see their prepared testimony here, here, here and here. redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity, also participated. The following is Lips’ condensed spoken testimony.

The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on Aug. 6 held a public hearing on “Challenges to Safely Reopening American Schools,” featuring former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan; Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Broward County (Florida) Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie; and Angela Skillings, a second-grade teacher in the Hayden-Winkelman Unified School District in Arizona. You can see their prepared testimony here, here, here and here. redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity, also participated. The following is Lips’ condensed spoken testimony.

As we have heard today, communities across the country are facing a difficult decision about how to begin the school year during the pandemic. The prospect of any child, teacher, or school employee contracting COVID-19 and facing the possibility of death or serious illness should weigh heavily on all policymakers involved with decisions affecting schools’ plans.

But it is critical that policymakers also recognize the serious risks associated with prolonged school closures, particularly for disadvantaged children.

Researchers studying the educational effects of school closures warn that time out of school results in months of lost learning, and that the learning losses are most acute for low-income students.

The bottom line is that prolonged school closures will create a large achievement gap for a generation of American children. Beyond these educational effects, prolonged school closures create significant risks for children’s health and welfare.

There is alarming evidence, which I describe in my written testimony, that prolonged school closures since the spring have endangered child welfare. Closures also have significant negative economic effects for parents. Many parents have been forced to choose between their jobs and their child’s care, and this challenge is most difficult for single parents.

The good news is that it is possible for schools to reopen.

Health experts — including the American Academy of Pediatrics — have issued guidelines for safely reopening schools with certain precautions, such as physical distancing, utilizing outdoor space, cohort classes to minimize crossover among children and adults, and face coverings for students (particularly older students).

And we are seeing many school districts choose to reopen across the country with in-person instruction or hybrid learning options.

According to a new analysis from the Center for Reinventing Public Education, 41 percent of rural districts and 28 percent of suburban districts plan to provide in-person instruction this fall. But most the nation’s largest school districts are not reopening with in-person instruction.

Seventy-one of the nation’s 120 largest school districts are beginning the school year with remote instruction and no in-person learning, based on FREOPP’s review. Altogether, these closed school districts serve more than 7 million children — including 1.4 million children living in poverty.

It is important to recognize that children from low-income families have fewer resources to learn outside of school than their peers. According to one estimate, rich families spend more than $9,000 out of pocket on their children’s educational and enrichment outside of school, while the poorest families spent just $1,400.

Today, families with financial means are working to create better options than remote learning — including homeschooling and setting up “pandemic learning pods” by forming coops with other parents and hiring teachers or tutors. But children from lower-income families have few options. Policymakers must address this inequality.

For example, states should use existing CARES Act funds to provide aid directly to parents in the form of education savings accounts or scholarships to support their children’s outside of school learning needs. Oklahoma, New Hampshire, and South Carolina are already doing this. Other states should follow their lead.

As Congress considers future aid packages for K-12 education, you should provide aid directly to parents to help disadvantaged children learn when their school is closed. There is precedent for providing emergency education relief in this manner.

After Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita in 2005, many children were displaced and had nowhere to go to school. Congress provided more than $1 billion in aid that followed affected children to a school of their parents’ choice, allowing them to continue their education.

If millions of children are unable to attend school this year, Congress should focus much of its aid in a similar manner — providing direct assistance to help children continue learning while schools are closed. In my written testimony, I discuss these and other recommendations for how school systems can prioritize and address the needs of disadvantaged children during the pandemic.

Since 1965, Congress has rightly focused federal education aid on promoting equal opportunity for at-risk children. In 2020, this will require focusing aid to support disadvantaged kids who can’t go to school.

The Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity will host an executive briefing on its recommendations for reopening and continuing American education during the pandemic on Thursday. Visit https://freopp.org/ for details.

Keys Gate Charter School in Homestead, Florida, is one of several campuses managed by Charter Schools USA that will begin the academic year with distance-learning only.

One of the largest public charter school operators in Florida has revisited a decision to open its brick-and-mortar locations for the coming school year, citing concerns over a spike in COVID positivity in some counties it serves.

Charter Schools USA, which operates 92 schools in five states, had informed families it would physically open all 14 of its South Florida schools. Last week, officials announced that the Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade County campuses would offer a “fully mobile classroom experience” instead.

Those schools will equip classrooms with voice-activated camera technology that will follow teachers around empty classrooms. Students will have a full view of the room as well as any materials a teacher wants them to see.

Officials say they will keep a close eye on COVID data and will have all 18,000 Charter Schools USA students back to in-person education as soon as possible. Teachers with health and safety concerns who are still hesitant to return to the classroom will have the option of teaching remotely.

In the meantime, the two CSUSA schools in St. Lucie County will offer three options: in-person instruction, fully mobile classrooms and a combination of in-person and mobile learning.

As schools continue to wrestle with reopening plans and what seems like the shortest summer break on record comes to an end, researchers have continued to churn out reports and surveys related not only to COVID-19 but to charter schools and per-pupil spending as well.

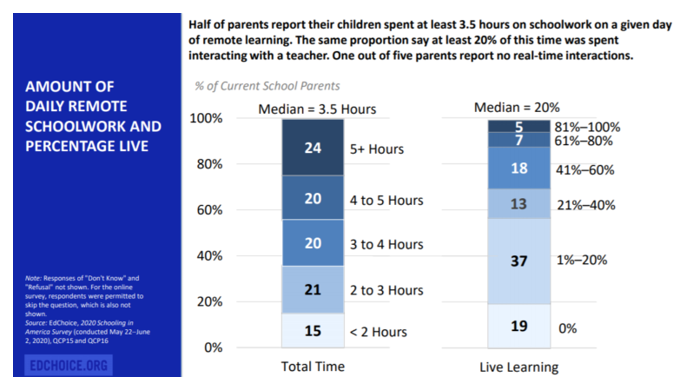

EdChoice, a school choice advocacy and research organization based in Indianapolis, released a survey on parent opinions regarding education during the pandemic.

According to the researchers, nearly 60% of parents with a child at risk for coronavirus complications said they would seek remote learning options compared to 39% of parents with a child not at risk. Additionally, Black parents were more likely to be seeking remote learning options than white parents, a finding in line with a previous survey conducted by Education Next that showed Black parents found greater satisfaction with remote learning than white parents.

A study by Ian Kingsbury from Johns Hopkins University and Robert Maranto from the University of Arkansas examined the impact of charter school regulations, finding that some regulations produce negative effects. Instead of protecting consumers, Kingsbury and Maranto concluded, bad regulations sometimes simply protect insiders.

According to the researchers, states with a high number of regulations like Texas, Ohio and Indiana saw Black- and Hispanic-run charter school applicants denied at far higher rates than white or Asian charter applicants.

“As states like California and Pennsylvania mull strengthening their charter regulatory regimes, they’d do well to take heed to ensure that people of color are stewards and not subjects of the charter schooling movement,” the researchers wrote. An Education Next article gives a good summary of the study.

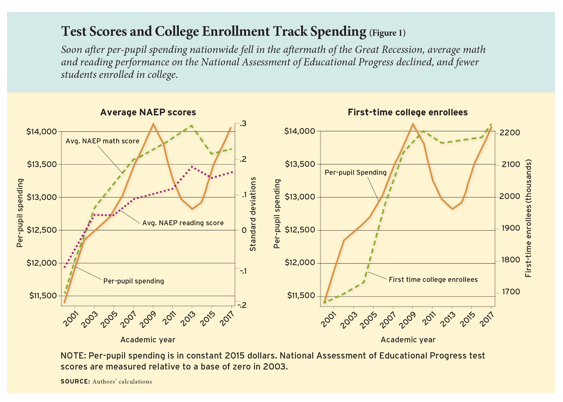

Finally, a study by C. Kirabo Jackson and Cora Wigger from Northwestern University and Heyu Xiong from Case Western Reserve University, summarized in Education Next, found the Great Recession negatively impacted student achievement and college attendance. The researchers argue that a decline in education budgets because of the recession may have caused these declines.

The researchers also found that budget cuts impacted Black students more than white students and may lead to a widening of achievement gaps. They note, however, that “A particular concern is that it is changes in families’ economic circumstances due to the recession, not reductions in school spending, that account for the decline in outcomes.” Indeed, the college attendance rate began declining in 2006, years before budget cuts to per-pupil spending.

Little Miss Ruffit

Little Miss Ruffit

Cried, “Mom, lets slough it

Who needs that school anyway?”

Said Mom, “Dear, we do.

Must work to feed you

You’ll learn your stuff there today.”

I see no handy solution to the “either stuck-at-home or stuck-at-work” dilemma of the Ruffit family. And I have sympathy, not only for the parent and child but, yes, for the public school systems – especially those in large cities.

Experts of every mind are announcing their own version of the ideal technique for reopening schools, and many of these sound plausible. This sort of civic conversation is good. Nevertheless, what stays plain and most regrettable is the continued assumption of most “authorities” that a small collection of government persons who are total strangers to both the individual child and parent still will be deciding where those kids from poor families in this neighborhood will learn their ABCs.

These outsiders will order the child to a school that the parents are unable to refuse because they can’t afford either to move to some well-set suburb or pay tuition at the private school they would prefer. They have tried to enroll Susie in the few charter schools that are allowed by the state over the howls of the union, but all are chock full or too distant.

One can admire the seriousness with which government authorities have taken today’s unique challenge; they have redesigned their programs for public schools with variety across the state. But sheer zeal is no solution to this deeper problem of choice for the poor, which is with us yet from the 19th century at the dawn of public education as we know it.

The motivation at that time was largely religious prejudice to be institutionalized in the kinds of schools which – with compulsory assignment of the poor – appeared most likely to rescue young minds from their ignorant parents’ un-American ideas.

I wish we could give this sudden swing toward decentralization of public schools three cheers as a retreat from prejudice and a salute to the dignity of the poor. Sadly, it is neither. The union can rest easy. There is no immediate threat to its dominion. And you mothers and fathers – best you keep working. You can still have late dinner at home and listen to your child’s experience of the day, wishing you could do something to help her.

I wonder what she makes of the role of parents in this society.

Pity Ms. Ruffit’s

Fate to go snuff its

Message from who knows where.

Well, sorry, but that’s how

We keep our world now.

Of parents so poor who’ll care?

Editor’s note: redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for Fox News Network and offered it to redefinED for republication.

Editor’s note: redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher wrote this commentary for Fox News Network and offered it to redefinED for republication.

Parents looking for a national consensus on whether schools should open in the fall won’t find one. But that’s okay. We don’t need one.

As soon as President Trump announced his support for reopening schools, teacher unions said he was “brazenly making these decisions.” So much for consensus. And this despite the fact that both proclamations said students should be kept safe, emphasized Centers for Disease Control guidelines on reopening (speakers on the White House panel cited no fewer than eight CDC reports, while unions called the documents “conflicting guidance”), and claimed to have the nation’s best interests in mind.

Well.

Luckily, many state officials and school leaders had already moved on. In April, Montana Gov. Steve Bullock said that schools could hold classes in-person immediately but left the decision to local educators. In Idaho, closures varied by school district, but some school leaders had students back in class by May. Governors and state officials have announced in-person summer school classes for Illinois, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Texas and Virginia.

Even if relatively few schools have thus far decided to have students return to the classrooms, that fact that some states have done so should change parents’ question from if schools will open in the fall to how quickly the process can happen.

“The CDC has issued guidance,” Vice President Mike Pence said at the White House event, “but that guidance is meant to supplement and not replace state, local, territorial, or tribal guidance.” What may be “conflicting guidance,” to unions is better described as “federalism.” 50 states, 50 different pandemics, 50 laboratories of democracy.

That’s the way it should be. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis coined the “laboratory” phrase, prefacing it by saying, “To stay experimentation in things social and economic is a grave responsibility.” We should be encouraged, then, that some local educators are not waiting for Washington to decide for them, and, likewise, that parents are not waiting on schools.

After the wild ride of sudden school closures in March, uneven attempts at online instruction through the spring, and a school year that seemed to have no official end date, polls showed more parents were considering educating their children at home. For those wondering if the 59 percent of respondents in a USA Today/Ipsos poll who said they may homeschool now really meant it, a headline last week—and weeks before school starts—from North Carolina’s North State Journal read “Homeschool requests overload state government website.”

Those not ready to homeschool will find it difficult if not impossible to return to work if schools are closed. Montana is not Virginia which is not New York City, and parents ready to homeschool in Greensboro, N.C., may be thinking differently than a family in Charlotte. Parents should be wary of press releases with advice on education from public or private national groups that use words like “comprehensive,” “nation’s schools,” or even “all.”

The Trump administration said that schools may lose federal money if they stay closed. Such a move would likely be challenged in court. But one problematic aspect of this threat is that it keeps the debate over who should be making decisions for the “nation’s schools”—again, beware the phrase—at the national level, a tussle between the federal government and nationally-focused special interest groups.

A more effective talking point for the administration would be to encourage the laboratories. For example: In areas where schools are closed, state lawmakers could give parents and students who wish to opt-out of those schools the students' per-student spending amount to use for homeschooling resources, private school tuition, tutors and more. Or erase district boundaries and allow students to choose a traditional school other than his or her assigned school.

The National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers, the nation’s largest teacher unions, will howl at the suggestions, but they should be loath to take the matter to court again. Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Montana could not prevent families from choosing a religious school when students use K-12 private school scholarships created by state law.

Unions regularly cite provisions in state constitutions that are rooted in religious bigotry when the groups sue to block such opportunities, but the High Court called precisely this language discriminatory in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, weakening the union’s position in 37 other U.S. states with similar provisions. The fight has already advanced to defending scholarships to religious private schools in Maine.

Washington should not force schools to reopen. But national officials can remind state lawmakers and parents there are alternatives. Short of a consensus on opening schools in August, that is the best news for everyone.