Riverview Charter School in rural Beaufort County, South Carolina, is one of 298 schools in the state designated as rural fringe, which means they are 5 miles from an urban area of at least 50,000.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jason Bedrick, a research fellow in the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, and Matt Ladner, director of the Arizona Center for Student Opportunity and reimaginED executive editor, appeared Thursday on thetanddd.com.

“All children in South Carolina should have access to the highest quality education possible.” So declared Gov. Henry McMaster in recently proclaiming School Choice Week in South Carolina.

To that end, the South Carolina legislature is currently considering a proposal to give families greater freedom to choose learning environments that align with their values and meet their children’s individual learning needs.

The proposal would create education savings accounts (ESAs), letting families access about $6,000 in state funds to pay for private school tuition, tutoring, textbooks, online courses, special needs therapy and numerous other educational expenses. Ten states have already adopted ESA policies, including five in the last two years.

It’s not hard to understand why.

The pandemic — and especially district schools’ response to it — awakened parents to the need for education choice. Unnecessarily long school shutdowns, mask mandates and concerns over the politicization of the classroom have propelled public support for education choice policies, like ESAs, to all-time highs.

A recent poll of likely voters in South Carolina, conducted by the South Carolina Policy Council, found six in 10 supported the ESA proposal. Support among African American voters was even higher, at 68%.

But not everyone is on board. The teachers’ unions and their allies are doing everything they can to block families from accessing alternatives to the district school system.

In an effort to peel away votes from South Carolina legislators representing rural areas, ESA opponents are arguing that choice policies either don’t benefit rural areas or are harmful to rural district schools.

For example, state Sen. Nikki Setzer, D-Lexington, argues that students in rural areas can’t benefit from the ESA proposal because they supposedly lack private options. “What real option are we giving them? Are we gonna let Johnny in Bamberg drive to Richland County?” he asked recently, “Give me a break.”

Meanwhile, Carol Corbett Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education, frets that education choice policies would supposedly create a “death spiral” for district schools, “especially in rural areas” because when “kids leave the system, they leave behind all kinds of stranded costs.”

These two claims — that there are no schooling options in rural areas and that rural schools are imperiled because so many students will leave for those options — are mutually exclusive. They cannot both be true, but they can both be — and indeed are — false.

To continue reading, click here.

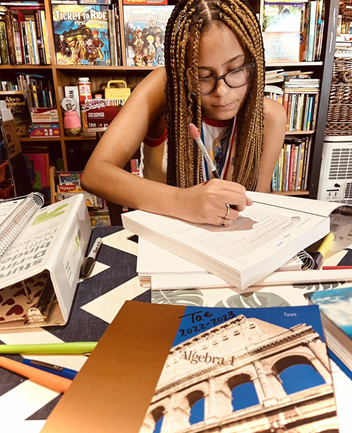

Tae Harvey, 13, attends a homeschool co-op in rural Williston, Florida, one day a week and works one-on-one with co-op founder Tracy Kirby for several hours on another day. Tae’s mom, Misty Dodd, says she’s seen “a 200% difference” in her daughter since she started attending the co-op..

WILLISTON, Fla. – When Misty Dodd’s daughter Taelyr was in third grade, her teachers told Dodd that “Tae” needed to be in a school with more rigor. Tae, now 13, was enrolled in the neighborhood school’s gifted program. But she was making straight A’s without breaking a sweat, and so bored, she was racking up demerits for being too chatty.

The teachers suggested a school in Gainesville. But for Dodd, it wasn’t an option. With traffic, it was 45 minutes to an hour from their home in Williston, a town of 2,700 surrounded by pine forest and pasture. And Dodd, a single mom, works 70 hours a week to make ends meet.

“I was embarrassed and frustrated,” said Dodd, who still cries at the recollection five years later. “I was thinking my daughter is going to get lost. What if she loses interest because it’s not challenging enough?”

“I was thinking, ‘I’m going to let her down,’ ” Dodd continued. “I thought, ‘She’s not going to get the education she deserves.’ "

Thankfully, the story of Tae and her mom has an almost perfect ending.

Almost.

Dodd found Tracy Kirby, a former public school teacher who started a home-school co-op on a farm full of trains. Kirby is now Tae’s teacher.

Tae attends the co-op one day a week, then works with Kirby one-on-one, in person, for several hours on another day. Kirby assigns Tae work for the week, and Tae touches base by phone or online as often as necessary.

For Tae and her mom, the arrangement works.

“What Mrs. Kirby does is amazing, and Tae loves it,” Dodd said. “I know I can trust Mrs. Kirby. There’s a 200 percent difference between now and before.”

“The main difference now is, I’m challenged,” Tae said. “Academically, there’s always something for me to do. And if there’s something else I want to do, I can ask, and Ms. Tracy can work it into the curriculum.”

By age, Tae is an eighth grader. But in most of her subjects, she’s performing at a ninth grade level or higher.

The only downside – and it’s a serious one – is cost.

Misty Dodd and her daughter, Tae

Dodd works two jobs – one as a clerk at the Florida Department of Motor Vehicles; the other as a waitress. It’s not easy paying for Tae’s education. Kirby doesn’t charge for the co-op programming, but there is a fee for the 1-on-1 tutoring. Dodd must also pay for books, a laptop, a printer, and other supplies.

A state-funded education savings account (ESA) that would pay for those expenses, and other learning supplements for Tae, would be “incredible,” Dodd said. “I work two jobs in part to pay for that. A scholarship would be a blessing.”

Florida does have an ESA. It’s popular and successful. But it’s limited to students with certain special needs. Tae is not eligible.

Florida also has the most expansive private school choice programs in the nation. But unlike ESAs, which can be used for a variety of services and providers, traditional school choice scholarships are limited to private school tuition. Dodd could qualify for a traditional scholarship, where eligibility is determined by family income. But it wouldn’t do Tae any good.

(Both the ESA and the income-based scholarships are administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Dodd said she never considered private school for Tae because Kirby’s approach is so good.

Kirby tailors the curriculum to fit Tae’s needs and interests. Tae takes many of her core academic classes through Florida Virtual School. She accesses electives through other online platforms (everything from typing to logic to archaeology). Kirby coordinates all of it, then tops it off with her own guidance and instruction and an emphasis on project-based learning.

For example, Tae is passionate about writing. So Kirby frequently gives her writing assignments, from essays to short stories. One time, Kirby asked Tae to study the past winners of a Florida speech contest. She wanted Tae to learn the techniques behind good speeches and to work on her public speaking skills.

“This propelled her to become an expert and figure out what made dynamic speeches,” Kirby said. “She doesn’t stop until she discovers the why.”

“I continuously find myself in shock over her writing,” Kirby continued. “She has a sharp imagination and adds humor. She can also be serious and argue a point.”

Tae is organized and driven. On her own, she read “The Diary of Anne Frank” in third grade and “The Yearling” in fourth grade. In fifth grade, Kirby gave Tae a thesaurus. She also showed Tae how she took notes in college, and Tae used Kirby’s system as a guide to create her own, better system.

“She’s unlike any student I have seen in all my years of teaching,” Kirby said. “The effort she puts in on her own is remarkable.”

Finances, though, are putting limits on Tae’s pursuits.

Tae is fascinated with forensic science and criminal psychology. Kirby said she’d love to look for STEM kits and online programs that mesh with Tae’s interests, and perhaps enroll Tae part time in a school that specializes in crime scene investigations.

“She’d love it,” Kirby said. “She’d be a little mad scientist.”

But all of that costs money Dodd doesn’t have.

An ESA would change that.

If it’s akin in value to the state’s school choice scholarships, it would cost taxpayers far less than per-pupil spending in Florida district schools. And for students like Tae, the return on investment would be invaluable.

Without Kirby, Dodd said, Tae might have become self-conscious about her intellectual interests and retreated into a shell. “She might have gone backwards,” Dodd said.

Kirby said other students have come to her co-op in that shell, shaped by past schooling experiences. In a different setting, they blossom into self-motivated learners like Tae.

If the state’s scholarships offered more flexibility, more students could access those environments.

For Tae and her mom, it’d be perfect.

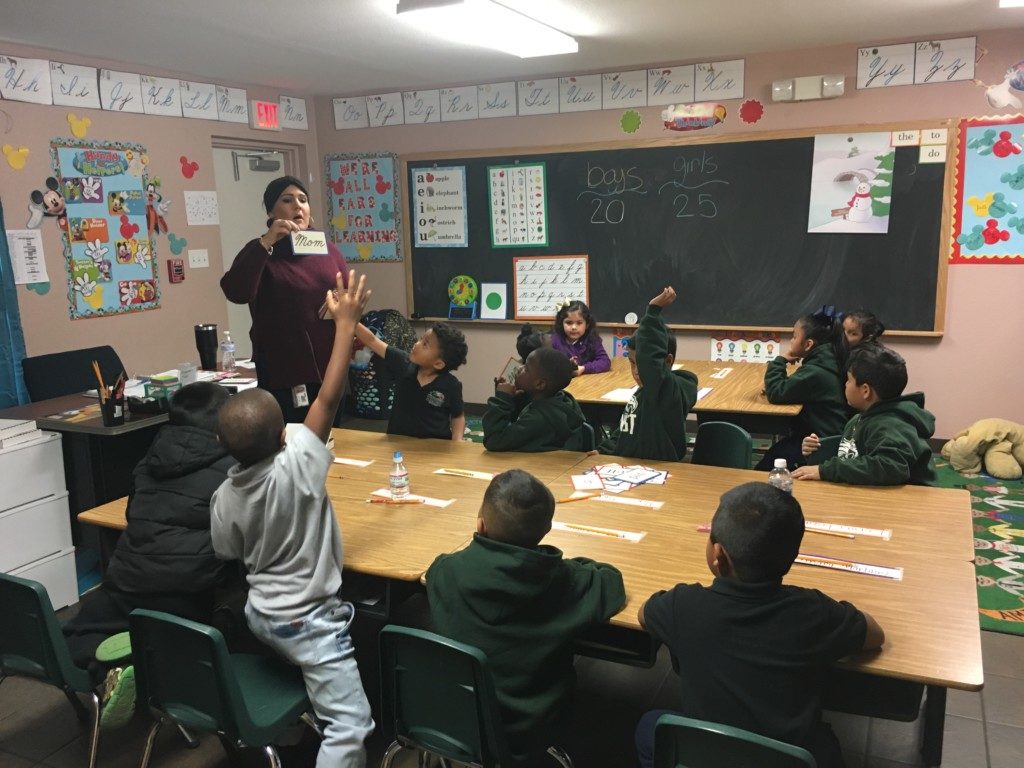

There's a lot of school choice going on in some of the most remote places in Florida. Here, Danyelle Juarez teaches her Kindergarten class at Harvest Academy Christian School in Clewiston, one of a string of small towns on the edge of Lake Okeechobee.

CLEWISTON, Fla. – It’s hard to think of anywhere in Florida more off the beaten path than the string of blue-collar towns on the rim of Lake Okeechobee. They’re snugged between the grassy, 30-foot-high dike that corrals America’s second-biggest lake, and a 450,000-acre sea of sugar cane that rolls south towards the Everglades. This is not palmy, beachy Florida. This is burning fields and smoking-sugar-mills Florida.

This is also school choice Florida.

The half-dozen towns that ring Lake Okeechobee are home to 10 private schools that serve more than 600 students using school choice scholarships. Four charter schools in the area serve another 600.

Harvest Academy Christian School in Clewiston, a town too small for a Starbucks, is one of these schools. It opened nine years ago with 12 students. Now it has 120. About 90 use the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students.* Five use McKay Scholarships for students with disabilities.

“I think it’s the best thing that could have happened,” said Sanjuanita Morales, 29, a stay-at-home mom whose three children attend Harvest Academy with tax credit scholarships. “There’s a lot of people that ask about the school and the scholarships and they say, ‘Oh that’s really cool you have options.’ “

The choice schools here are myth chippers. There’s the myth that school choice can’t work in rural areas because there are too many hurdles – including too few students – to make non-district schools viable. Then there’s the myth that rural school districts, often their area’s biggest employers, are especially hostile to choice because they need to keep themselves viable.

Both myths solidified during last year’s confirmation hearings for Betsy DeVos. Both continue to endure in stories like this, this and this. Yet both seem at odds with what’s happening in Florida, which has one of America’s most diverse educational ecosystems.

School choice war? Not here.

Thirty Florida counties are defined as rural, and this year they’re home to more than 80 scholarship-accepting private schools (like this one). Together, those schools are serving 3,828 tax credit students, 999 McKay students and 287 students using Gardiner Scholarships, an education savings account for students with special needs.* Many also serve students using Florida’s pre-K voucher.

Three of those counties abut Lake Okeechobee.

Hendry County, home to Clewiston, has 39,000 residents scattered over 1,190 square miles. If Hendry were a state, its population density would rank near Nevada’s. Okeechobee County on the north end of the lake is a tad less remote (on par with Colorado); Glades County on the west, two tads more (think New Mexico). The east end of the lake rests in Palm Beach County, but Pahokee and Belle Glade are 40 miles, and a galaxy, from the glitz of West Palm Beach.

As for the other myth: Listen to Jesse Windham, principal of Harvest Academy.

“Everyone thinks it’s a war,” he said about school choice. “It’s not here.” (more…)

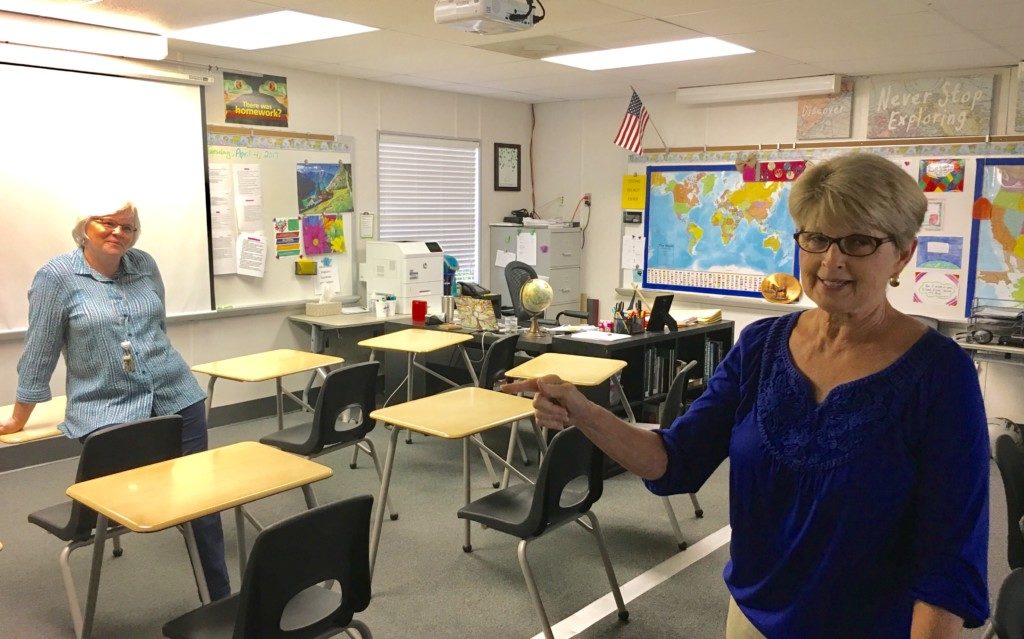

School choice can't work in rural areas? Tell that to Judy Welborn (above right) and Michele Winningham, co-founders of a private school in Williston, Fla., that is thriving thanks to school choice scholarships. Students at Williston Central Christian Academy also take online classes through Florida Virtual School and dual enrollment classes at a community college satellite campus.

Levy County is a sprawl of pine and swamp on Florida’s Gulf Coast, 20 miles from Gainesville and 100 from Orlando. It’s bigger than Rhode Island. If it were a state, it and its 40,000 residents would rank No. 40 in population density, tied with Utah.

Visitors are likely to see more logging trucks than Subaru Foresters, and more swallow-tailed kites than stray cats. If they want local flavor, there’s the watermelon festival in Chiefland (pop. 2,245). If they like clams with their linguine, they can thank Cedar Key (pop. 702).

And if they want to find out if there’s a place for school choice way out in the country, they can chat with Ms. Judy and Ms. Michele in Williston (Levy County’s largest city; pop. 2,768).

In 2010, Judith Welborn and Michele Winningham left long careers in public schools to start Williston Central Christian Academy. They were tired of state mandates. They wanted a faith-based atmosphere for learning. Florida’s school choice programs gave them the power to do their own thing – and parents the power to choose it or not.

Williston Central began with 39 students in grades K-6. It now has 85 in K-11. Thirty-one use tax credit scholarships for low-income students. Seventeen use McKay Scholarships for students with disabilities.

“There’s a need for school choice in every community,” said Welborn, who taught in public schools for 39 years, 13 as a principal. “The parents wanted this.”

The little school in the yellow-brick church rebuts a burgeoning narrative – that rural America won’t benefit from, and could even be hurt by, an expansion of private school choice. The two Republican senators who voted against the confirmation of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos – Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine – represent rural states. Their opposition propelled skeptical stories like this, this and this; columns like this; and reports like this. One headline warned: “For rural America, school choice could spell doom.”

A common thread is the notion that school choice can’t succeed in flyover country because there aren’t enough options. But there are thousands of private schools in rural America – and they may offer more promise in expanding choice than other options. A new study from the Brookings Institution finds 92 percent of American families live within 10 miles of a private elementary school, including 69 percent of families in rural areas. That’s more potential options for those families, the report found, than they’d get from expanded access to existing district and charter schools.

In Florida, 30 rural counties (by this definition) host 119 private schools, including 80 that enroll students with tax credit scholarships. (The scholarship is administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog.) There are scores of others in remote corners of Florida counties that are considered urban, but have huge swaths of hinterland. First Baptist Christian School in the tomato town of Ruskin, for example, is closer to the phosphate pits of Fort Lonesome than the skyscrapers of Tampa. But all of it’s in Hillsborough County (pop. 1.2 million).

The no-options argument also ignores what’s increasingly possible in a choice-rich state like Florida: choice programs leading to more options.

Before they went solo, Welborn and Winningham put fliers in churches, spread the word on Facebook and met with parents. They wanted to know if parental demand was really there – and it was.

But “one of their top questions was, ‘Are you going to have a scholarship?’ “ Welborn said. (more…)