In 2022 I wrote a piece here at Next Steps declaring myself President of the “Religious Charter Schools Should Be Permitted, Mandatory and Non-existent” club. Every other group under the sun operates charter schools and infuses the curriculum with their point of view, which is fine because charter schools should be viewed as state contractors, as they are out here in the 9th Circuit. Moreover no one is ever forced to attend.

In that context, telling Lutherans etc. that they are some kind of menace to society that we must protect children from seems both bigoted and silly. It is also contrary to the principle of religious neutrality. Moreover, the equivalents of religious charter schools operate in Europe, and while it may not be optimal, it is hard to argue that such a prospect is catastrophic.

I also attempted to explain that the charter movement of today is not the movement of decades past. We’ve spent a couple of decades passing charter school laws perfectly designed not to open many actual charter schools. When states passed laws perfectly designed not to pass many charter schools, national charter groups sang the praises of the new laws.

This is not as strange as it sounds. This is not to say that it isn’t pathetic — it is in fact entirely pathetic — but it is not unheard of. Public choice economists long ago identified a Baptist and Bootlegger problem whereby sincere opponents (Baptists in this case are the unions and their groupies) and opportunistic incumbents (in this case charter management organizations with a legal team that can file a 900+ page application etc.) team up to throttle competition…err…I meant ensure quality charter authorizing.

Actually, I had it right the first time.

If you’ve been keeping half an eye on the Supreme Court for the last 20-plus years, you’ll know that the majority (delightfully) takes a dim view of discriminating against people or groups based upon their religious affiliations. I could be wrong (it has happened plenty of times before) but I’m thinking it is pretty clear how this case is likely to go.

Even if/when the high court allows religious charter schools, enthusiasts need to remember that this is what awaits even if you win the case:

The B and B alliance does not want m(any?) new charter schools to open, and both will be aghast at the idea of religious charter schools. I am not going to help them dream up insidious ways to discriminate against religious groups. If I did, it wouldn’t take me long to dream up five or six ways. On principle, I am with the religious charter school enthusiasts. Color me skeptical that this effort will prove a productive way to provide new schools and seats, but non-discrimination and an experimental mindset should prevail.

Enthusiasts should, however, understand the politics of what they are getting into.

Editor’s note: The NAEP will release 2024 fourth and eighth grade math and reading scores Wednesday. Buckle up!

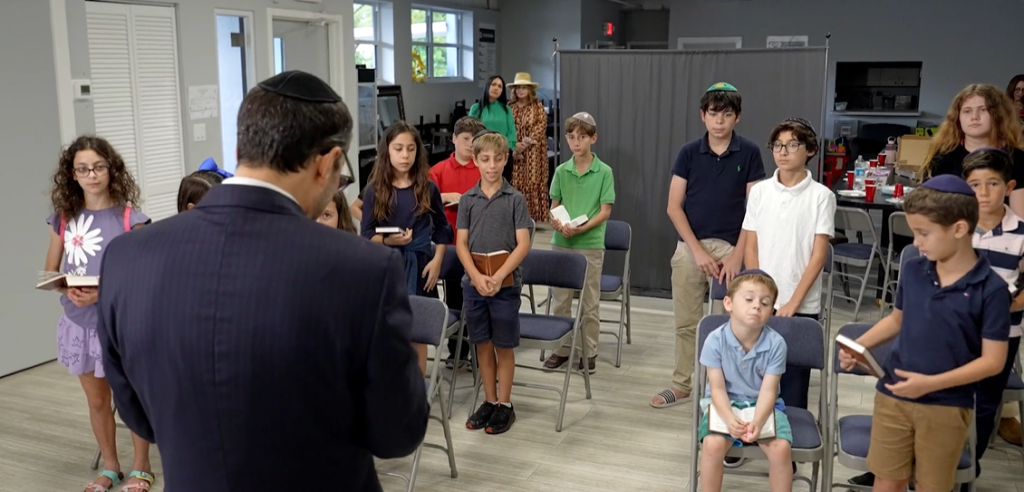

An outgrowth of more than two decades of strong secular and Jewish education leadership, Shorashim Academy prioritizes low tuition, premier learning, a warm family feel, Jewish identity and a strong connection with the State of Israel.

Rabbi Isaac Melnick likes to call it “the holy grail.”

Though the Orthodox Jewish leader and founder of Shorashim Academy doesn’t intend it as a religious reference, it serves an apt metaphor for what education entrepreneurs cite as their most difficult challenge: finding and securing a home to carry out their dream.

“A saying from one of our great sages of the last 100 years is that to start a yeshiva, or a Jewish school, you have to have a certified ‘Meshugener,’ a crazy person to take this on themselves,” Melnick said. “Because on paper this doesn’t make sense. If someone wants to be an entrepreneur, this is probably one of the riskiest, diciest ways to start a business. It’s just fraught with uncertainties.”

Melnick’s quest began last year after he was named a fellow in the Founders Program of the Drexel Fund, a national non-profit organization with a mission of equipping entrepreneurs to start or expand innovative learning programs by providing training and grants.

The fund also provides funding to support the new schools in areas that seek to help students in underserved areas. Florida and other states with robust education choice scholarship programs, provide fertile ground for qualifying founders and startups.

“I’d say that’s probably the biggest hangups,” said Eric Oglesbee, an alumnus of the Drexel Fund founders program who now serves as its director. He said the topic came up at a recent information session in which fellows said the biggest lesson learned over the past seven months had been the difficulty of finding and securing a location.

“It takes forever to find a spot that that can check all the boxes and get all the approvals,” Oglesbee said. “You have to figure out what’s not going to work but also know your model well enough to know what’s going to work.”

Oglesbee said while searching for a site for his River Montessori High School in South Bend, Indiana, three possible locations fell through before he and his team finally landed one. In addition to finding the site, founders must then contend with local government rules regarding zoning, construction and fire codes.

Because the rules are set locally, they often force founders to navigate a patchwork of regulations of varying stringency depending on the location of possible sites. A Utah lawmaker filed a bill this year to create uniform rules for innovative learning communities, often referred to as microschools. But the measure, which had been modeled after laws governing charter schools, failed in the Senate.

“Just because a site is in an area zoned for a school, it doesn’t mean you get approval,” Melnick said. “It just means you get to have a conversation.”

That conversation typically involves a list of responsibilities the entrepreneur must bear, such as a traffic study to make sure the roads can handle the car trips the new school will generate, as well as a list of renovations to bring buildings up to the latest codes.

Those responsibilities also come with a hefty cost that the founders and their team must bear.

Gretchen Stewart, a Drexel Founders fellow from Tampa, Florida, is working to open Smart Moves Academy, a motion-based school that caters to low-income students with learning differences. Since 2021, she has been dealing with myriad challenges posed by her unique model, as well as soaring rent costs and a lack of overall availability in the school’s catchment area.

“It just became clear right away that this was going to be problematic,” said Stewart, a former public school teacher who drew the inspiration for the school while writing the dissertation for her doctorate in special education and educational neuroscience at the University of South Florida.

Stewart said she first considered churches near the east Tampa community she planned to serve, but the spaces were being used by nonprofits providing feeding programs for those facing food insecurity.

“That kind of wiped out the spaces we could have considered,” she said.

She added that larger churches in the area already leased to private schools, and many older churches lacked the space needed for her program, which requires each classroom to be 900 to 1,000 square feet to accommodate physical activity-based learning.

The model also depends on access to enough green space for students to play and learn outside three times a day.

“A lot of schools are in strip malls where kids don’t go outside or are playing on a blacktop portion of a parking lot, which is not something our model can accommodate,” Stewart said.

The same goes for access to natural lighting, which Stewart says is critical to learning and good health.

For now, the program is operating as a summer camp at USF, but even that is not large enough to allow for necessary gym equipment.

If all that wasn’t enough of a barrier, Tampa rents are skyrocketing.

“We looked at one place near USF, and they wanted $35,000 a month, and that’s without utilities and taxes,” she said. “We’re trying to serve families from lower-income communities, families who have historically not had access to private education and allow them to take advantage of Florida’s robust school choice program.”

Stewart has applied for grants and is talking to philanthropists about the needs her school would meet. While she says everyone agrees that it’s a good idea, no one has been willing to donate enough to fully fund it.

Some organizations, like the Cristo Rey Network of Catholic high schools, have been fortunate to secure transformational gifts, like the $7 million donation the Orosz family made to buy a 75,000-square-foot vacant building to start a new school in Orlando.

“Space is our last hurdle,” Stewart said.

Like his fellow Drexel founder, Melnick also failed to land big gifts.

He made pitch after pitch to wealthy individuals in South Florida about buying a building and leasing it to Shorashim Academy, but no one was willing.

“I thought that would be a win-win,” he said, adding that even when an educator entrepreneur finds a lease deal, landlords usually want to collect rent months before the school is able to open and generate revenue to pay the expenses.

“You’ve really got to have the perfect storm, the perfect set of circumstances, in order to execute on that vision,” he said.

Melnick also approached synagogues, but many already hosted schools. One possibility fell through because the synagogue didn’t match the Shorashim Academy leaders’ Orthodox beliefs. The situation seemed so daunting that Melnick and school leaders hit the phones in hopes of finding leads.

“Regretfully, it made me a little bit cynical,” he said.

Their persistence, or what Melnick credits as divine intervention, recently brought good news.

Shorashim Academy will open this fall at the Soref Jewish Community Center in Plantation, Florida.

They have added a coveted new tab to the school’s website: Location.

Tampa Torah Academy, a private Orthodox Jewish school, will provide a challenging and well-rounded, age-appropriate curriculum emphasizing critical thinking, problem solving and independent research in diverse bodies of Judaic and general studies.

Abundant sunshine, greater opportunities for remote work, affordable housing, and school choice scholarships have attracted many young Jewish families from the Northeast to Florida. Now, a group from Queens, New York, is moving to the Tampa Bay area to open Tampa Torah Academy, a private Orthodox Jewish school.

The school will be led by Rabbis Ariel Wohlfarth and Yirmiyahu Rubenstein, who will serve as deans of the academy. The school will serve students in preschool through eighth grade, though leaders hope to add high school grades if enough parents express interest.

The school will be housed at 5209 Tampa Palms Blvd. in a rambling white building with dormer windows and an inviting wraparound porch that formerly served as a day care center. Renovations are nearly complete, and leaders expect to start classes by the end of this month.

The timing for the school is optimal, as more than 39,700 Jewish people live in the Tampa Bay counties of Hillsborough, Pinellas and Pasco, according to 2020 figures from the Public Religion Research Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to independent research about the intersection of religion, culture and public policy.

From left to right: Rabbi Ariel Wohlfarth, Rabbi Yirmiyahu Rubenstein, Rabbi Yossef Stulberger

Rubenstein explained that interest for the school came from parents in Tampa who contacted the Rabbinical Seminary of America, also called Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim, and Orthodox families seeking to leave New York for Florida. He said eight Orthodox families will be coming down from New York with him.

The school is part of the services provided by the Kollel, a group of dedicated Jewish families who live, learn, and teach in the community. The outreach center will also offer classes for adults on topics related to Judaism as well as community events.

Tampa Torah Academy is an affiliate of the Rabbinical Seminary of America, of which both Rubenstein and Wohlfarth are graduates. The organization is connected to similar Torah academies throughout the country, including in Orlando and South Florida.

Rubenstein said the school day will begin with religious education followed by secular studies such as math, reading, science and social studies in an Orthodox environment that will include kosher meals and a calendar that allows students and staff to observe Jewish holidays.

Rubenstein, a husband and father of four young children, explained that Jewish day schools are not luxuries for families, who need their children to receive Judaic education in addition to traditional academics and be raised in their culture.

“The Tampa Torah Academy is a response to the growing need of the Jewish community in Hillsborough County,” said Allan Jacob, a North Miami Beach nephrologist who also is chairman of Rabbinical Seminary of America. “There is a high probability that this effort will succeed in attracting more and more families of faith to the area to live and to the school for their children’s education. These families will contribute in a very positive way to the overall business and moral climate of the county.”

Jacob said the growth in the Tampa Bay area is replicating what happened in south Florida as more New York families seek refuge from that state’s high taxes, high housing costs and expensive private school tuition.

“We have seen similar expansion and growth in parts of south Florida as our communities grow,” he said. “All this is only possible because of the scholarships available through the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship and Step Up For Students.”

(Step Up for Students, which hosts this blog, manages the Family Empowerment Scholarships for Educational Options and for students with Unique Abilities as well as the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, the New Worlds Reading Scholarship for struggling readers and the Hope Scholarship for students who have experienced bullying at their district schools.)

Figures from the Florida Department of Education show enrollment in Jewish day schools statewide grew in 2020 to 12,482 students from 10,623 in 2018. The number of such schools grew to 64 from 50 during that time.

Rubenstein thanked state leaders for approving the legislation that made the scholarship programs possible and enabled the school to open.

“We want to provide for these children and do all these great things, and obviously it costs money,” he said. “I feel it’s important for parents to have that choice, and the scholarships give them that choice.”

Once open, Tampa Torah Academy will be the third Jewish day school in Hillsborough County, joining Hillel Academy of Tampa and Hebrew Academy of Tampa Bay.

There is no Jewish day school In Pinellas County, but the Tampa Bay International School includes a Jewish studies program and receives support from the Jewish Federation of Florida’s Gulf Coast.

For more information about the school and an upcoming open house, call (813) 485-5817 or email info@tampatorahacademy.org.

The mission of First Academy-Leesburg is to equip students spiritually for service in the body of Christ, morally for citizenship in the United States of America, and academically for success in higher education or their chosen vocation.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Sunday in The Villages Daily Sun.

First Academy Leesburg is a ministry of First Baptist Church of Leesburg, but that doesn't mean every student who goes there attends that church, let alone is Baptist.

"I would say 20% of our students attend FBC Leesburg," said Greg Frescoln, administrator for First Academy Leesburg. "Another 60% attend around 80 different Protestant churches. We have students who are Catholic, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim. We even have students who consider themselves atheist."

But regardless of faith system or beliefs, Frescoln said, the students and their parents have one thing in common — a desire for a quality education.

"Parents know that their children are going to be cared for, and the kids know that they will succeed and be loved," Frescoln said. "A lot of our students and parents found out about us through word of mouth, they hear from the community."

First Academy is one of several religious private schools that dot the tri-county area. The schools offer an alternative to traditional public schooling, with an emphasis on faith-based programs and curriculums.

"We started in 1988 with 29 students from kindergarten through second grade," Frescoln said. "We now have 460 students from grades K-12. We will be graduating our 500th student next year."

"Train up a child in the way he should go, even when he is old he will not depart from it." — Proverbs 22:6

According to the Florida Department of Education, 1,681 religious private schools are listed in the state's Directory of Private Schools, which can be found at fldoe.org. Private schools are required by statute to complete an annual online survey to be included in the directory. However, it is possible that some schools have been omitted by the state.

To continue reading, click here.

Killian Hill Christian School in Gwinnett County, Georgia, is one of 831 private schools serving more than 153,000 students in the state. A strong community of parents, faculty and staff are dedicated to preparing students to be Christian leaders of the future.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday on georgiarecorder.com.

A new school voucher bill sponsored by Georgia Senate Pro Tempore Butch Miller moved forward in a Senate committee Tuesday.

Senate Bill 601, or the “Georgia Educational Freedom Act,” would provide a $6,000 scholarship to nearly all of Georgia’s approximately 1.7 million public k-12 students to switch to a private school.

Children should not be limited to the school they happen to live near, said Miller, a Gainesville, Georgia, Republican who is running for lieutenant governor. He argued giving parents the means to send them elsewhere will help them succeed.

“I couldn’t be more thankful for the teachers and employees of our school systems, not just in my community, but around the state,” he said. “However, every child is different, every system is different, and not everyone in our state is blessed with the opportunities my children have had, and I think that we’ve seen through the pandemic that there are more options, parental options for our schools.”

School vouchers have been a perennial issue at the Capitol, with opponents decrying them as a means of funneling public dollars to less accountable private institutions.

Miller argued against that idea with a common talking point in the “school choice” movement. While the proposed law would take away the state portion of the money allocated to educating a transferring student, the school would still receive the local portion of the funding, resulting in a net gain, he said.

To continue reading, click here.

Des Moines Christian School, one of more than 240 private schools in the state, provides kindergarten through 12th grade education programming on one campus. The school’s stated mission is to equip minds and nurture hearts to impact the world for Christ.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday in the Des Moines (Iowa) Register.

Advocates pushing for more state aid for private schools crowded into the Iowa Capitol rotunda Tuesday as Republican lawmakers determine whether they have enough support to pass Gov. Kim Reynolds' hallmark education priority.

The rally featured remarks from national proponents, including a pair of former students who used private school voucher programs in Florida and Ohio. The duo, known as the School Choice Boyz, now travels the country to lobby for similar measures.

They were joined by parents of private school students in Iowa and state Republican legislators supportive of the proposal. Many speakers talked about how access to private schooling was important to support their Christian faith.

Alana Gentosi, a parent of students at Des Moines Christian School in Urbandale, said she and her husband have been able to make it work with their careers to pay for a private school education but are passionate about expanding school options in Iowa.

To continue reading, click here.

Rutland Area Christian School in Rutland, Vermont, one of 126 private schools in the state, is an independent, interdenominational Christian school guided by principles and values revealed in the Bible.

Editor’s note: This commentary from John McClaughry, vice president of the Ethan Allen Institute and former vice chair of the Vermont Senate Education Committee, appeared Tuesday in Vermont’s Bennington Banner.

This year and the ensuing biennium are likely to be landmark years for the future of parental choice in education in Vermont.

In June 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Espinoza v. Montana that if a state offers education tax credits, it must offer them to students choosing sectarian schools as well as public schools. The court said that excluding sectarian schools burdened the plaintiffs’ right to the free exercise of their religion.

That ruling triggered at least three similar cases by Vermont plaintiffs seeking to use state tax dollars to benefit their children in independent and sectarian schools.

The Valente case argues that parents in tuition towns should be able to have their school districts pay their children’s tuition directly to a religious school. Last month, parents filed another suit (Williams) to require Barstow Unified Union District to pay tuition for two children attending the same Roman Catholic school.

Another case from Glover argues that if any student is allowed to take school district tuition funding to a sectarian school, then all students, not just tuition town students, should also enjoy that “common benefit”. Meanwhile, a very similar case (Carson v. Makin) has made its way from Maine to the U.S. Supreme Court, which held oral argument in December.

But the government school lobby is urging the Legislature to put a stop to what could be a costly hemorrhage of students – and money – out of public schools. The four defenders of government schooling are the Vermont School Boards Association, Vermont Superintendents Association, Vermont Principals Association, and the Vermont-NEA teachers’ union.

Their Feb. 23 joint letter to the Senate Education Committee sets out their argument that expanding parental choice brings “a morass of complicated legal and logistical questions.” Their central message comes through loud and clear: Forget funding of children. Fund only public schools.

To continue reading, click here.

Cole Valley Christian School in Boise, Idaho, is one of 143 private schools in the state that serve 17,626 students. Its mission is "to develop each student’s body, mind and spirit in the hope he or she will impact a lost world for Jesus Christ."

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday on idahostateman.com.

Idaho lawmakers on Tuesday narrowly shot down a bill that would create scholarship accounts that families could use for students’ tuition and fees at private grade schools. The motion to hold the bill in committee passed 8-7 after multiple lawmakers and members of the public raised concerns that it would harm public schools and wasn’t a constitutional use of state dollars.

The bill would have allocated an estimated $12.7 million of Idaho public schools’ budget in the first year for the scholarships. Families with children in kindergarten through 12th grade would have been able to receive about $5,950 in state funds, according to the current estimates.

The funds could then be used for expenses including tuition and fees at private schools or non-public online learning systems, certain tutoring services and technology.

Under the bill, parents would have had to apply for the scholarship through the State Department of Education and promised not to enroll their student in public school during the time they’re receiving the funds.

To continue reading, click here.

Two states, Maine and Vermont, have devised ways to circumvent the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Espinoza vs. Montana.

States can’t discriminate against religious schools because of their religious identity. But can states discriminate if the school teaches religious things?

If you thought this debate was settled by the U.S. Supreme Court last summer, think again.

Two recent circuit court rulings say yes, states can discriminate against religious instruction. Lawyers for the Institute for Justice briefed the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this month and are waiting to hear if the nation’s highest court will resolve this issue once and for all.

The 2020 landmark Supreme Court case Espinoza v. Montana was supposed to settle the debate over “separation of church and state” in publicly funded education programs. That ruling determined that, “A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

Despite this proclamation, Maine and Vermont have found clever ways to ignore the court ruling.

Maine has been offering publicly funded private education through a town tuition assistance program since 1873. The program is available to students living in towns without an available public school. Students may choose to attend a public school in another town or attend a private school. That private school, however, cannot be religious in nature.

But just a few months after the Espinoza ruling, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the religious exclusion in Maine’s program.

The court got clever with the wording. The judges argued that the Espinoza case prohibited states from discriminating against the schools’ religious status, whereas Maine was not discriminating against religious status but prohibiting religious use.

In other words, Maine’s ban on selecting private religious schools was not over the school’s religious identity, but because the religious school taught religious things.

It may be a distinction without meaning.

Could religious schools in Maine receive publicly funded tuition if they did not provide the publicly funded student religious instruction? That is unclear, as Maine’s prohibition appears to be a blanket ban.

The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a similar argument in a case over Vermont’s tuition program earlier this month.

The Institute for Justice, which represented parents, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court to take up the Maine case.

“Maine is discriminating against students that pick religious schools and the High Court should grant review and put an end to such exclusions nationwide,” Institute for Justice managing attorney Arif Panju said in a press release. “By singling out religion—and only religion—for exclusion from its tuition assistance program, Maine violates the U.S. Constitution.”

The U.S. Supreme Court justices will consider on June 24 whether to grant review.

You can read the Institute’s Supreme Court brief here and supplemental brief here.

*Updated to clarify the results of the Vermont case decided on June 2nd.

PHOTO: Institute for Justice

The Institute for Justice appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in March, asking the justices to hear the case of three Maine families wishing to send their children to private religious schools.

The issue to decide: Can the state’s school choice program discriminate against private religious schools based on what they teach?

Maine’s town tuition program, created in 1873, requires towns without public schools to send local children to other public school districts or pay for private school tuition. However, Maine’s program prohibits towns from paying tuition at private religious schools.

The plaintiffs in the case, Carson, Gillis and Nelson v. Hasson, argue Maine’s law violates the U.S. Constitution and the recent Espinoza decision. The 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, however, rejected that argument last year.

Under Espinoza, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could not prohibit religious schools from participating in publicly funded programs due to their religious status.

Maine’s law requires participating private schools to be “nonsectarian.” The state courts and 1st U.S. District Court of Appeals argue this does not violate Espinoza.

The state’s law under § 2951(2) simply states that the school must be “a nonsectarian school in accordance with the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.”

Exactly how the First Amendment defines nonsectarians schools is not clear, but the state of Maine comes up with a rather clever way to defend its discrimination: “While affiliation or association with a church or religious institution is one potential indicator of a sectarian school, it is not dispositive. The Department's focus is on what the school teaches through its curriculum and related activities, and how the material is presented,” the state’s department of education claimed.

According to the state, prohibiting religious instruction does not violate the U.S. Constitution or the recent Espinoza decision because they are discriminating against religious uses, not religious status.

The 1st U.S, Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, arguing that Maine’s requirement of “nonsectarian” schools is not a prohibition on the religious status of a school, but a prohibition on religious uses.

Under this interpretation, a religious school could participate in Maine’s town tuition program so long as it didn’t teach religious things.

“The state flatly bans parents from choosing schools that offer religious instruction. That is unconstitutional,” says IJ senior attorney Michael Bindas.

Several groups, including a coalition of 18 states, filed amicus briefs urging the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case.