TALLAHASSEE, Fla.– Amanda Thompson said she will be the president of the United States.

Not wants to be or hopes to be but will be.Amanda Thompson said she will be the president of the United States.

Not wants to be or hopes to be but will be.

Just like she will be the attorney general of Florida, the governor of Florida, and the United States attorney general before reaching the Oval Office.

“That’s the plan,” she said. “I’m going to get there.”

Of course, there is some prep work to be done before she begins a career of service to her state and country.

First, Amanda, 17, is set to graduate this May from St. John Paul II Catholic High School (JPII), where she will be class valedictorian. She attends the parochial school in Tallahassee with the help of a Florida education choice scholarship managed by Step Up For Students.

Then it’s off to Harvard University, where she plans to double-major in government and history and earn a degree from its prestigious law school. Along the way, Amanda will pitch for the Crimson softball team with designs on leading the program to its first appearance in the Women’s College World Series.

As that unfolds, Amanda is determined to play softball in the Olympics. She has attended tryouts for Team USA and is a member of the United States Virgin Islands national team.

Taken separately, any one of her goals is ambitious.

But combined?

“She has very, very high expectations,” said JPII Principal Luisa Zalzman. “She’s a go-getter, a high achiever. She has a drive that is very mature for her age.”

“She's done everything she's ever put her mind to,” said Amanda’s mother, Ashley Williard. “She said she wanted to be valedictorian, and I said, ‘OK, go be valedictorian.’ And she did it.”

Amanda is a bundle of energy and confidence. On the softball field, she has a running dialogue with everyone – teammates, opponents, coaches, umpires. In the classroom, she’s involved in every class discussion.

If you had approached her in August 2022 as she took the initial steps of her high school journey and told her she would graduate first in her class and be a member of Harvard Class of 2030, she would have been stunned.

“I would have said, ‘You got the wrong person.’ The difference between me then and me now is astronomical, and I think it’s because I attended this school,” she said. “It has to be.”

Amanda was a star as she rose through the ranks of the Tallahassee youth softball programs. Her parents, Ashley and James Thompson, envisioned their daughter earning an athletic scholarship to college. They were thinking of a high-end academic university like Duke or Notre Dame. That’s how Amanda, who attended her district schools until eighth grade, landed at JPII.

“We wanted a high school that was college-focused,” Ashley said. “Education is what we were looking for, and we could not have done it without Step Up For Students. No way could we afford to put her in that situation.”

There were “little things,” Amanda said, that shaped her academic future.

Her freshman English teacher encouraged her to write outside the margins during tests and essays.

“He said, ‘You don’t have to stay within this box. If you know more, write more on the paper.’ That stuck with me,” Amanda said.

Her freshman world history teacher announced to the class that Amanda scored the highest on the first test of the year.

“He congratulated me,” she said. “I thought that was insane.”

Midway through that semester, Amanda realized she had A’s in all her classes. That’s when she began to believe in herself as a student. Future valedictorian?

“Why not?” she said.

Amanda took AP World History as a sophomore and aced the AP test.

“That’s the class where I learned to learn,” she said.

Also, her love of history and government was born in that class, Amanda said. She can name all the countries of the world, tell you where they are located, and identify the flags.

“I’m working on my capitols,” she said. “It’s my hobby.”

Amanda took Spanish I and II in middle school and passed each, but not with grades that would stand out on a high school transcript. Sara Bayliss, JPII’s college advisor, suggested that Amanda retake those courses.

“She said the grades weren't good enough, that I could do better,” Amanda said.

Amanda retook both classes. She asked Principal Zalzman, a native of Venezuela, for tutoring help. The result was a pair of grades that fit proudly on the transcript Amanda sent to Duke. Duke was her dream school for education and softball.

And then Harvard called.

At midnight on Sept. 1 of her junior year – the first day college coaches can contact 11th graders – Amanda received a phone call from the Harvard softball coach.

“I didn’t even know they had a softball program,” Amanda said.

Intrigued, Amanda accepted a recruiting visit to the university located just outside of Boston. That trip marked the end of her Duke dreams.

“I want to make a difference in this world, and I think Harvard is the perfect school for me,” she said.

Terrence Brown, JPII’s softball coach, has watched Amanda emerge as an Ivy League student and a Division I softball player good enough to attend Team USA tryouts and earn a spot on the national team of a small territory with Olympic ambitions.

“She’s goal-oriented, and she doesn’t let anything get in the way of achieving those goals,” he said. “She’s worked very hard to get to where she’s going.”

Ashley and James are proud parents, but Ashley said they won’t take too much credit for Amanda’s success.

“We have nothing but pride,” Ashley said. “She is self-driven, self-motivated. We try to provide motivation. She’s missed proms and dances because of softball travel and schoolwork, and that was all her decision.

“There are a lot of sacrifices made to go along with this. She’s not afraid of hard work. She says she’s going to do something, and she goes out and does it.”

Step Up For Students, the nation’s largest education choice scholarship funding organization, is pleased to announce it has been renewed as an SFO for the 2026-27 school year following a unanimous vote by the Florida Board of Education.

Step Up has served Florida for more than two decades, starting with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program. The nonprofit currently administers five programs and one stipend with over 520,000 students, and processes 10 million financial transactions.

On Feb. 1, Step Up once again set the new national record in education choice: It received a record 200,000 applications in the first three days of Season Open, and by the 10th day it had received a record 300,000 applications. It is currently nearing 400,000 applications.

“Step Up For Students is grateful for the confidence the Board of Education has shown in our ability to manage the state’s education choice programs,” said Step Up CEO Gretchen Schoenhaar. “There is no initiative of this size, scope and complexity in the country, and we are honored to serve the parents, students, schools, providers and vendors as well as to partner with the DOE and legislature in Florida.”

When Florida in 2023 made all K-12 students in the state eligible for a scholarship program and transformed the programs into education savings accounts (ESAs) that gave parents more flexibility in how they spend their children’s scholarship funds, it unleashed unprecedented demand from families. Step Up has responded with technological innovations and process improvements that have defined the customer experience.

Central to that is Step Up’s Education Market Assistant (EMA), an online platform to manage an ESA program from start to finish, including the onboarding of parents through the online application, the processing of those applications and the reporting features required by the state. EMA also serves as the platform for education service providers, vendors, and private schools to engage with parents.

EMA brings together parents and providers in an efficient marketplace and ensures all ESA funds are spent effectively and efficiently consistent with state law, including preventing fraud. The platform has influenced similar technologies across the nation.

For the second year in a row, Step Up has realized significant improvements in performance even as participation in the state’s scholarship programs continues to grow:

Step Up welcomes continued collaboration with the Florida Department of Education and the Legislature to find solutions to systemic challenges in the education choice scholarship programs.

PALATKA, Fla. — All Risa Byrd wanted to do was start a little preschool. That’s it. But then the former public school teacher got swept up in one of the most epic education stories in American history. Now her fast-growing school is the latest example of what’s possible when school choice is the new normal.

In 2022, Byrd retired from a 26-year teaching career to start Little Sprouts Learning Center. The goal was modest: Get her granddaughter’s academic journey off on the right foot.

A few months later, though, Florida lawmakers passed, and Gov. Ron DeSantis signed, one of the most sweeping school choice bills of any state, ever. Suddenly, every student in Florida was eligible for a state-supported choice scholarship.

Byrd didn’t realize it at first. But her school had caught a wave.

In the fall of 2023, Byrd added kindergarten and first grade, starting with eight students in those grades. She called the school for the higher grades Putnam Classical Academy.

By the fall of 2024, Putnam Classical had 50 students in grades K-5.

By the fall of 2025, it had 234 students in grades K-6, in addition to 60 in preschool.

Now Byrd’s looking for a whole other building to house a separate middle school. When she announced plans via Facebook, 111 students signed up in three days.

“Parents are desperate for their kids to be well educated,” Byrd said, particularly those from underserved communities. “They’ve been written off.”

Byrd is one of hundreds of former public school teachers who have leveraged Florida’s choice scholarships to create their own learning options. They can be found in every corner of the state, even in rural and semi-rural counties like Putnam, where a paper mill is the biggest private employer, the biggest town has 10,000 people, and the best-known landmark may be a blast-from-the-past diner.

The parents driving demand aren’t looking for anything exotic, Byrd said. They just want safe schools with top-quality academics, high expectations, and no drama.

“Parents got the word that we don’t play. That’s the biggest draw,” Byrd said. “They’re fed up. They know kids can’t learn, and teachers can’t teach, if there’s sheer chaos in the classroom.”

Byrd’s story may be a particularly dramatic example of what’s happening in Florida, and particularly symbolic.

More than half of Florida’s 3.4 million students are now enrolled in something other than their zoned neighborhood schools, and more than 1 million are enrolled outside of district schools entirely. Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that Putnam Classical leases a century-old building that once served as the local school district’s headquarters.

Despite the name, Putnam Classical isn’t truly classical yet. Byrd said she and her staff, which includes 20 teachers, will transition to a more recognizable “great books” curriculum within two years.

The first order of business is to establish a higher rate of basic literacy.

A self-described “data nerd,” Byrd is a “science of reading” adherent and a huge fan of Natalie Wexler, author of “The Knowledge Gap” and a leading proponent of using a content-rich curriculum to boost vocabulary and comprehension.

For the early grades, Putnam Classical uses an explicit, evidence-based phonics curriculum developed by the University of Florida. For the higher grades, it uses the highly regarded Core Knowledge curriculum for language arts, science, and social studies.

“If you teach these kids to read, you will change the trajectory of their lives,” Byrd said. “Then they can be an astronaut, a chef, anything they want to be.”

Byrd said as a public school teacher, she earned a reputation for working well with struggling readers, so more and more were sent her way. It became obvious, she said, that many students acted out because they couldn’t read well.

One time, she said, she stopped a 10th grader from disrupting her classroom, then took her out to the hallway to talk. The girl broke down and told her, in between sobs, “I’d rather everyone in that room think I’m a b---- than think I’m stupid.”

In three years, Byrd said she’s expelled two students. The school isn’t orderly because it’s draconian about discipline, she said. It’s orderly because kids are achieving academically and are proud of themselves. “When you learn to read,” Byrd said, “school becomes a lot more fun.”

About half of the students at Putnam Classical are Black or Hispanic; about 75% would be eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch in public school. The school does not charge tuition beyond the amount of the choice scholarship, which averages about $8,000 statewide and is far less than what districts spend.

Most of the students who switched to Putnam Classical were not reading at grade level when they arrived, Byrd said. Some incoming second graders didn’t know their letter sounds.

But now?

Now more than 60% are showing average or better growth compared to their peers nationwide, according to the STAR reading assessment Putnam Classical uses. In other words, students who were previously losing ground in their prior schools are now catching up and starting to get ahead.

Dalton Crews chose Putnam Classical for his 5-year-old, Delilah. He said he attended a private elementary school before moving on to public school and thought it built a good foundation for academics and character. He wanted the same for his daughter, and thankfully, he said, choice made it possible.

“I love the teachers. They communicate really well. They always tell me what’s going on,” said Crews, who installs fire sprinklers for a living. “They tear up when the kids leave. That’s love. They’re good people.”

Shentae Roberts said her 10-year-old granddaughter, Ja’Zyiah, was receiving good grades in her prior school, even though it was obvious to her family that she was struggling with basic material.

Her daughter tried contacting the school to get more information, she said, but never got a response. That’s why, in 2024, her daughter switched Ja’Zyiah and younger brother, Hakiem, to Putnam Classical.

“Best thing she did,” Roberts said.

Roberts said her granddaughter initially struggled at Putnam Classical, too. But the teachers gave her the attention and instruction she needed, she said.

The result: Ja’Zyiah “came back 10 times stronger,” Roberts said. “All the staff get to know the children, and they’re responding to them. They’re pulling the children to the next level.”

Byrd said more good things are ahead, not just for her school.

Even though Florida has been a national leader in private school choice for a quarter century, Byrd said she didn’t know much about it until HB 1, the landmark legislation Gov. DeSantis signed in 2023. Now, though, she realizes the game-changing potential not just for families but for teachers.

“Every public school teacher says, ‘If I were the boss, I would do it this way,’ “ Byrd said.

Well, now’s their chance.

By Lauren May and Ron Matus

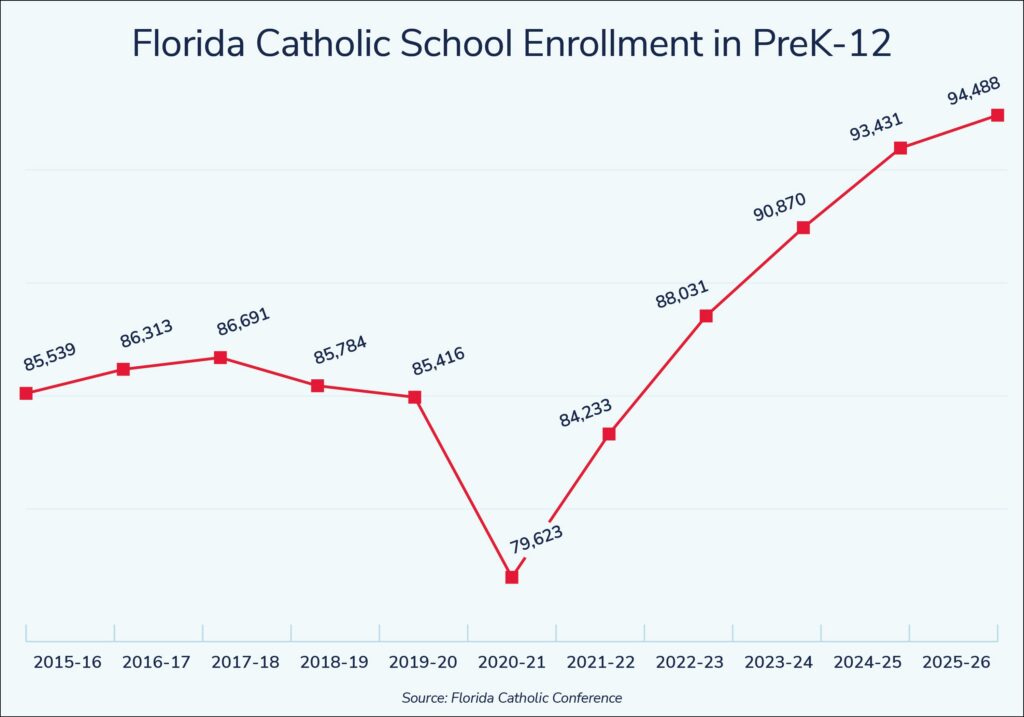

Catholic school enrollment in Florida is up again this year, rising 1.1% to 94,488 students, according to the latest numbers from the Florida Catholic Conference.

The continued growth is likely to bolster Florida’s reputation as the national standout in Catholic schooling. Through last year, Florida Catholic school enrollment was up 12.1% over the past decade. Nationally, it was down 13.2%.

To spotlight the trend lines, we published a special report in 2023, “Why Catholic Schools in Florida Are Growing: 5 Things to Know,” followed by update briefs in 2024 and 2025.

In that spirit, here are five things to know about the 2025-26 numbers:

The trend continues. This year marks five years of consecutive growth. Since 2020-21, when enrollment dipped in the wake of the pandemic, Catholic school enrollment in Florida is up 18.7%.

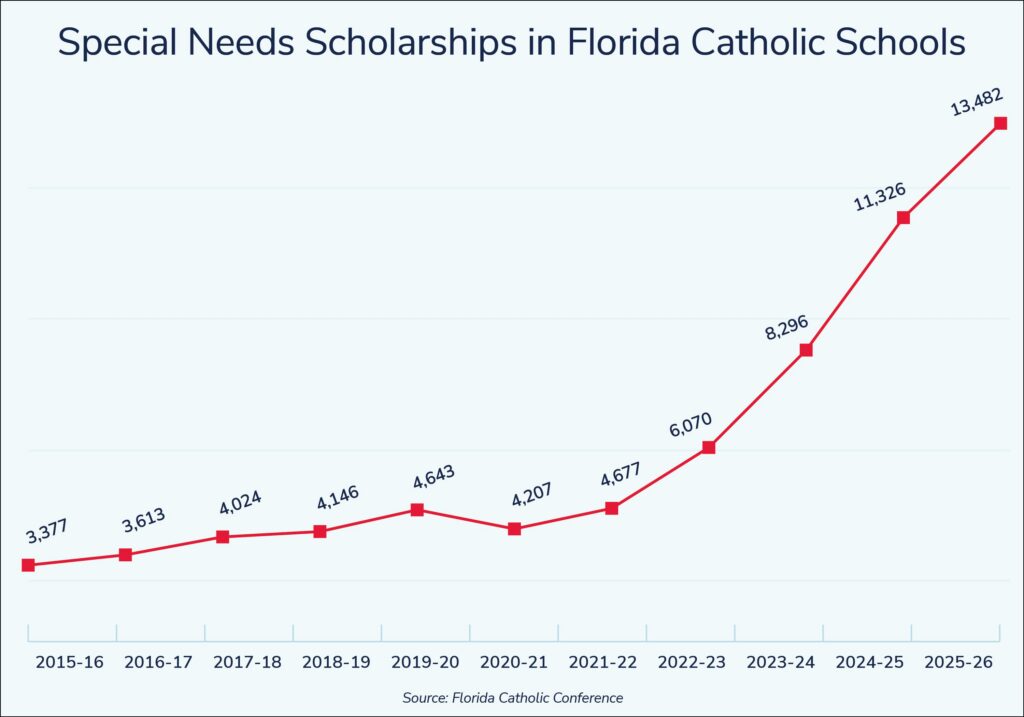

Special needs surge. Students with special needs are a leading factor. This year, Catholic schools in Florida are serving 13,482 students who use the state’s Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities. That’s up 19% from last year and triple the number from five years ago. FESUA students now encompass one in seven of all Catholic school students in Florida.

Non-Catholic students. Catholic schools have a long history of serving a diverse array of students. This year, 20% of students in Florida Catholic schools are non-Catholic, up from 14% a decade ago.

Choice scholarships are critical. In 2022-23, the year before choice in Florida became “universal,” 47.2% of all Catholic school students in Florida used choice scholarships. This year, 92.1% use them.

Context for the trend line. This year’s enrollment increase is smaller than any of the past five years. Time will tell whether that’s an anomaly. But it’s worth noting that except for a la carte learning, K-12 enrollment in Florida is slowing all over:

It’s likely that demographic shifts, including falling birth rates and declining immigration, are significant factors here. With private schools, it’s also possible that barriers such as zoning and building codes are preventing supply from better meeting demand. Last year, a Step Up For Students survey of parents who were awarded choice scholarships but didn’t use them found one in three said there were no seats available at the schools they wanted.

One final note: This post, not to mention our reports on Catholic education in Florida, wouldn’t be possible without the Florida Catholic Conference. FCC Director of Accreditation Mary Camp has been carefully tracking the enrollment and scholarship data for years. We are grateful to partner with the FCC and particularly indebted to Mary.

About the authors

Lauren May is Vice President and Head of the Federal Scholarship Tax Credit Program at Step Up for Students and a former Senior Director of Advocacy at Step Up For Students. As a proud graduate

of the University of Florida, she received her bachelor’s degree in special education

and her master's degree in early childhood education. She then completed another

master's degree in educational leadership from Saint Leo University. A former

Catholic school teacher, early childhood director, and principal, she was honored with

University of Florida’s “Outstanding Young Alumni” award in 2018. As a believer

that parents are the first and best educators of their children, Lauren loves working

with families across the state and beyond to ensure they can find and make

use of the best educational options for their children.

Ron Matus is Director, Research & Special Projects, at Step Up For Students. He

joined Step Up in 2012 after more than 20 years as an award-winning journalist,

including eight years as the state education reporter for the Tampa Bay Times, the

state’s biggest and most influential newspaper.

Updated Feb. 10, 2026

Record breaking interest continues with more than 400,000 students who have applied for Florida’s K-12 education choice scholarships for the 2026-27 school year.

Step Up For Students, the nonprofit organization that administers 98% of the state’s scholarships, opened applications for the 2026-27 school year on Feb. 1. A record 200,000 applied during the first three days.

By mid-day Feb. 10, a total of 300,106 students had applied for scholarships, which represents an 11.7% increase over the same 10-day period last year. By Friday morning, Feb. 27, a total of 401,507 students had applied.

Step Up For Students CEO Gretchen Schoenhaar said last week that the organization’s team and systems were ready for the surge of interest. Step Up’s technology systems processed 15% more applications on the first day this year than at the same time last year. Of the families who called for assistance, more than 90% reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the support they received.

“Another record number of applications on our opening weekend shows that Florida families increasingly value options in their children’s education,” Schoenhaar said. “Step Up For Students smoothly processed the higher demand and is prepared to support families every step of the way.”

During the 25-26 school year, more than 525,000 students have been funded on Florida’s K-12 scholarship programs to access learning options of their choice. If these students were counted as a single school district, it would be the largest in the state and third largest in the country. That makes Florida the national leader in education options.

However, not all students whose families apply end up being awarded or funded.

Step Up is focused on supporting growth. By the end of the year, Step Up expects to process 3 million reimbursements and a total of 3 million MyScholarShop e-commerce transactions.

Current scholarship families have until April 30 to renew their scholarships for the next school year. All families who want a PEP scholarship must also apply by April 30.

Private School and Unique Abilities Scholarship applications will be available through Nov. 15 for families who want a new scholarship.

Applications and more details are available here.

We will continue to update the numbers in this post until applications close.

VENICE – He is not afraid.

Lyra Kerr wants to make that clear.

He is not afraid to climb a ladder that rises 29 feet above ground. He’s not afraid to stand on the small platform near the top of that ladder and reach for the bar that will swing him over the safety net.

Lyra is not afraid to hook his knees on the bar and dangle as he swings.

And he’s certainly not afraid to release his grip and spin once, twice, three times before bouncing to a stop in the net.

Yes, Lyra wears a harness and is assisted by two trained trapeze artists, but he’s 6, and the climb and the swinging and the spinning could be unnerving for a beginner, let alone one his age.

But, said his mom, McKenna Rodgers, “He’s fearless.”

“It’s not scary,” Lyra said. “It’s super fun.”

In fact, he added, it’s “the most super fun” thing he does.

For 90 minutes two days a week, Lyra is the daring young man on the flying trapeze.

He trains under world-renowned trapeze artist Tito Gaona at Gaona’s trapeze academy in Venice. The fee is reimbursed through his Florida education choice scholarship, managed by Step Up For Students.

Lyra, his stepsister and stepbrother each receive the Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program. PEP provides parents with flexibility in how they spend their scholarship funds.

The scholarship enables McKenna to home-educate all three, who are enrolled in Florida Virtual School. She said her stepchildren, both teenagers, have improved scholastically since receiving the scholarship, especially in reading.

Lyra is just beginning his academic journey. McKenna is curious about where it will lead him and how, with PEP, she can tailor his academic needs and interests.

“I’m really happy to have access to it,” she said.

Lyra makes it look easy. (Video courtesy of McKenna Rodgers.)

The scholarship has paid for extracurricular activities for all three, including circus camp in the summer. Lyra is the only one who returned for training classes.

Tito Gaona said that Lyra can go as far as he wants to in the sport.

“Trapeze is a lot of fun, addicting. Once you get on a piece and you really like it, there's no end, because you fall in love with it because it's fun,” he said.

Venice, known as the “Shark's Tooth Capital of the World” for the tiny finds buried in the sand along its beaches, was once known as the “Winter Home of the Greatest Show on Earth.”

From 1960 to 1992, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus brought circus performers, workers, and animals to Venice during the offseason.

McKenna, born and raised in Venice, has fond childhood memories of seeing the performers train during the winter, especially the trapeze artists.

Tito Gaona’s Trapeze Academy is located near the municipal airport. When McKenna drove by with Lyra, she would point at the students swinging through the air and tell him she always wanted to do that when she was his age.

One day, Lyra said he wanted to be a trapeze artist, and McKenna decided she was going to make it happen.

“It wasn't a vicarious thing,” she said. “It was just something we had around here that is not common and is unique to the area. The circus had its winter headquarters here, and should keep it alive in a way. Performance art is important.”

And Lyra did have some practice flying. Sort of. They lived for a time on a houseboat, and Lyra often dived into the water.

“I jumped off the boat,” he said. “Off the roof, really.”

Looking for ways to harness Lyra’s energy, McKenna had already enrolled him in gymnastic classes. Tumbling through the air was a logical next step for a boy who loves to climb trees and dangle from bars in the playground near their Venice home.

Among the many perks of home education is that parents can set the daily schedule. This allows McKenna to keep some mornings free to take Lyra to the beach.

“No one’s there,” she said. “It’s my favorite time.”

Like a typical 6-year-old with boundless energy, Lyra’s interests are all over the place. He loves to swim, fish, play video games, and play with LEGOs. Right now, he is constructing “The Lord of the Rings: Barad-dûr,” the dark tower found in Middle-earth.

He even tried his hand at racquetball.

Nothing, though, beats the thrill of learning the trapeze.

The climbing, dangling, dropping, spinning.

To Lyra, none of it is scary.

It’s the most super fun.

AVE MARIA, Fla. – Toby and Nicole Mickelson were thinking about moving from Minnesota even before they heard about school choice in Florida. The weather, the politics, and the taxes were all getting to be too much, plus Nicole’s parents had recently become snowbirds with a winter home in southwest Florida.

Still, it wasn’t clear which warmer, less expensive, more conservative state they might move to.

But then a friend in Florida posted praise on Facebook for the state’s private school choice scholarships, which the Florida Legislature and Gov. Ron DeSantis had made available to every single student, beginning in the 2023-24 school year and are administered by Step Up For Students.

Toby and Nicole were stunned.

“I said, ‘Can you believe this even exists?’ Nicole said, “He said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ “

“Once we found out about the Step Up money, it (Florida) was a shoo-in.”

This was in the summer of 2024.

In early 2025, the Mickelsons applied to get their kids into Rhodora J. Donahue Academy, a classical Catholic school in Ave Maria, a predominantly Catholic community about 30 miles from Naples. In April 2025, their kids were accepted.

Incredibly, the family found the perfect house in Ave Maria and sold their home near Minneapolis almost simultaneously. By July, they were Floridians, with a month to spare before school started.

“We pinch ourselves every day,” Nicole said. “We’re so grateful to be here.”

The Mickelsons aren’t alone.

The Sunshine State has become a magnet for a whole new breed of transplants. We don’t have good numbers to quantify the trend, yet, but it’s easy to find families who moved here wholly or in part because 1) Florida offers generous school choice scholarships to every family, and 2) The education landscape is increasingly diverse because of all that choice, with more options for more families all the time.

At one school for students with special needs in Jacksonville, the families of 24 students — 10% of the entire student body — moved to Florida to access the school and the scholarships. At Donahue, according to the Diocese of Venice, at least two dozen students fit that description. Meanwhile, at a school for students with autism in the Tampa Bay area, a half dozen families moved from other countries or Puerto Rico.

The Mickelsons said families in Minnesota who hear about Florida’s choice scholarships initially “don’t believe it,” Nicole said. “They think it’s too good to be true.”

But, as the Mickelsons learned, they’re real.

Toby is an occupational safety manager for a commercial kitchen company and a member of the Air Force Reserves. Nicole is the vice president of sales for her family’s long-distance trucking business.

In Minnesota, they sent their kids to classical Catholic schools. For a big family, that wasn’t a breeze financially. Tuition per child averaged nearly $10,000 a year. “You can’t sustain that,” Nicole said.

Commuting was a challenge, too. One school was 20-30 minutes each way; the other, 30-40 minutes. “We lived in our cars,” Toby said.

The Mickelsons had some familiarity with Florida.

Four years ago, Nicole’s parents bought a home in Fort Myers, where they live for half a year. And three years ago, the Mickelsons visited Ave Maria University while they were checking out colleges with their oldest child. The university is also in the community of Ave Maria.

It was then that they learned about Donahue Academy, which is also a classical school.

Classical schools “teach a lot of classic books, like Dante’s ‘Inferno,’ not New Age-y things,” Toby said. For Donahue to also be a classical school was “icing on the cake.”

At the time the Mickelsons applied, Donahue had 440 students and a long waiting list. The Mickelsons weren’t sure they had a shot. But thankfully, the school was also in the midst of a huge expansion that would allow it to serve 615 students.

Donahue could be the poster child for another Florida-centered education trend, the revival of Catholic schools. Unlike Catholic schools in much of the country, Catholic schools in Florida are growing again. No region of Florida is showing more growth than the Diocese of Venice, which includes the cities of Fort Myers, Naples, Sarasota, and Bradenton.

“My husband said, ‘Let’s apply, let’s do the paperwork. If they get in, that’s our sign to move,'" Nicole said.

After praying and fasting, they got a thumbs up.

The Mickelsons have seven children. The oldest is in college. The next-oldest is homeschooled. Four attend Donahue, in grades 9, 7, 5, and 2, respectively. The youngest is a year old.

Nicole said school choice wasn’t the only reason for the move to Florida, but she put it at the top of the list, followed by politics, taxes, weather, and her parents living nearby. She said Donahue probably wouldn’t have been affordable without the choice scholarships.

In Ave Maria, the Mickelsons no longer worry about the long commutes, either. They live a few blocks from the school, so the kids bike there. “It’s like a dream,” Nicole said.

The plan is for the kids to graduate from Donahue, then attend Ave Maria University.

Nicole and Toby are both able to work remotely. And now that everything in Florida is working out so well, word is getting back to their friends in the Gopher State.

One family recently pulled their kids out of Catholic school because they could no longer afford it. For now, they’re homeschooling. But thanks to school choice, Florida looks mighty enticing.

Said Nicole, “I have a lot of Minnesota friends who want to move to Florida now.”

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Luz Acosta-Pandolphi was happy to be among the crowd gathered in the state Capitol courtyard Thursday afternoon to celebrate National School Choice Week. For her family, education choice is multigenerational.

Her daughter went to an Avant School of Excellence, which serves students in elementary, middle and high school at locations in Tallahassee and Florida City near Miami. Now, her two grandsons attend the school.

“It is a school where they fit in perfectly,” she said. One grandson has dyslexia and now can read at grade level, thanks to Avant, she said. State K-12 school choice scholarships make it affordable to send both boys.

“We wanted to be here to support choice,” Acosta-Pandolphi said.

She wasn’t alone. About 1,000 students showed up with their parents and school leaders to celebrate Florida’s many learning options and the fact that the Sunshine State is a national leader in education choice.

They sang the national anthem. They listened to a group of students at a classical charter school recite Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1837 poem “Concord Hymn,” which includes themes of sacrifice and freedom. They danced.

Several state lawmakers joined the celebration. As bills were being debated inside, it was all harmony in the paved courtyard. Only smiles, red and yellow balloons, and a celebration of the right of families to choose the best education for their children.

“How meaningful it is to stand here with you today, surrounded by families and students and teachers and education leaders whose lives are shaped every day by the power of the right educational fit,” said state Rep. Jennifer Canady, R-Lakeland. “Here in Florida, we are doing something truly special.”

Canady, a former teacher who holds a master's degree in special education, is the chairperson of the House Education & Employment Committee and was elected to be Florida’s first female House speaker in 2027.

Other state representatives who spoke included Reps. Michelle Salzman, R-Pensacola; Alex Rizo, R-Hialeah; and Yvette Benarroch, R-Marco Island.

School leaders stood up and praised state leaders for realizing that when it comes to education, one size does not fit all, and for empowering parents to direct their children’s education.

The celebration was co-sponsored by Americans for Prosperity Foundation and the National School Choice Awareness Foundation, both 501c3 organizations. Shenell Ellerbe, said choice had made a difference for her daughter, Subi, who attends the Digital Academy of Florida, a virtual school that Ellerbe said best fits Subi’s unique needs.

“It also provides flexibility, which is good because we travel,” Ellerbe said. She said Subi, who is in high school, is thriving and wants to attend college and study botany. She said having the ability to choose the best fit for Subi has made a significant difference for her academically.

“We felt it was important to come out here and show our support for choice,” Ellerbe said. The season open for scholarship applications for the 2026-27 school year is Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to apply.

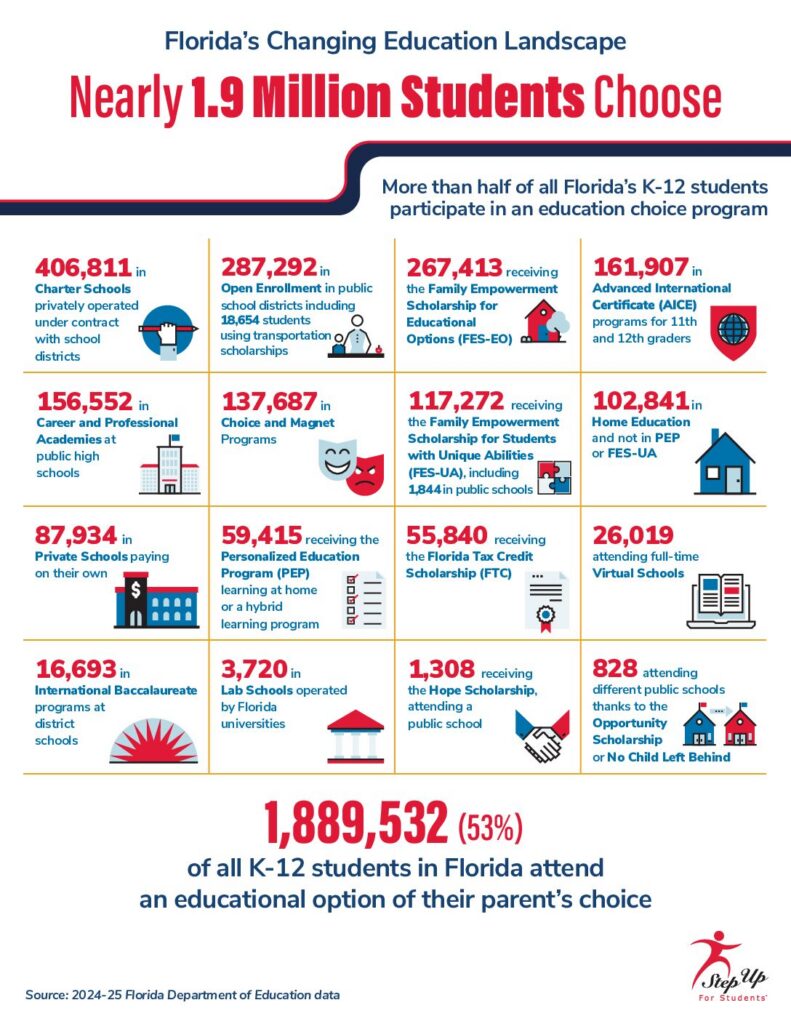

Florida’s K–12 education landscape continues to shift toward choice. During the 2024–25 school year, 53% of all K–12 students — 1,889,532 children — attended a public, private, or home education option of their parents’ or guardians’ choice. Just one year after crossing the 50% threshold for the first time, Florida’s school choice participation grew by nearly 100,000 additional students.

“Each year, Florida families have made it clear that they want more options for their children’s education,” said Gretchen Schoenhaar, CEO of Step Up For Students, the Florida non-profit that administers the state’s education choice scholarship programs.

“Increasingly, parents and guardians are willing to mix and match private and public resources to choose the ones that work best for their family.”

Since the 2008–09 school year, Step Up For Students, in collaboration with the Florida Department of Education, has tracked enrollment across a variety of choice programs. The 2023–24 school year represented a historic milestone: the first time more than half of all K–12 students in the state attended a school of choice. The 2024–25 school year continued that upward trend.

The Changing Landscapes report draws from Florida Department of Education data and removes, where possible, duplicate counts to provide a clearer picture of school choice participation. For example, it adjusts for home education students supported by the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA) and eliminates double-counted students in career and professional programs. It also excludes prekindergarten students in FES-UA and programs such as Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten (VPK), as the report focuses solely on K–12 education.

While many families still choose their neighborhood public schools, Florida’s education system now offers a broad range of options to meet diverse student needs. As in past years, public school choice remains dominant, occupying four of the top five spots in overall enrollment. Charter schools are the most popular single option, followed by district open enrollment programs, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options (FES-EO), career and professional academies, and Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) programs for upperclassmen.

The largest increases in enrollment occurred in the FES-EO program, which has merged with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, and the Personalized Education Program (PEP), a scholarship that helps fund education at home.

Among public school options, AICE enrollment grew nearly 17%, career and professional academies grew 6.2%, and open enrollment grew 4.6%. While overall district enrollment appeared to decline slightly, these public school choice options still grew more than charter schools (independent public schools), which grew just 2.3%. This may suggest that school districts could benefit from expanding their own menu of diverse school options to better retain families.

Choice remains strong within Florida’s public school system. More than 1.2 million of the state’s 2.9 million public school students attended a school of choice, while another 688,000 students outside the public system enrolled in private schools or home education programs.

A newer option to keep an eye on is district schools offering classes and services to students on an education choice scholarship, paid for with their scholarship funds. Currently 37 of Florida’s 67 districts have been approved as providers with Step Up For Students, and another 11 are in the process of being approved. These arrangements further blur the line between public and private and emphasize that the focus remains on the individual needs of students.

With so many options available, Florida’s education system has entered a new phase. Choice is no longer an alternative; it is the norm. Families routinely evaluate multiple pathways, and whether they select a different option or remain in their assigned public school, they are making an active choice. The result is an education landscape in which public, private, and home education options coexist and evolve together, reflecting the reality that students and families have different needs, and that those differences matter.

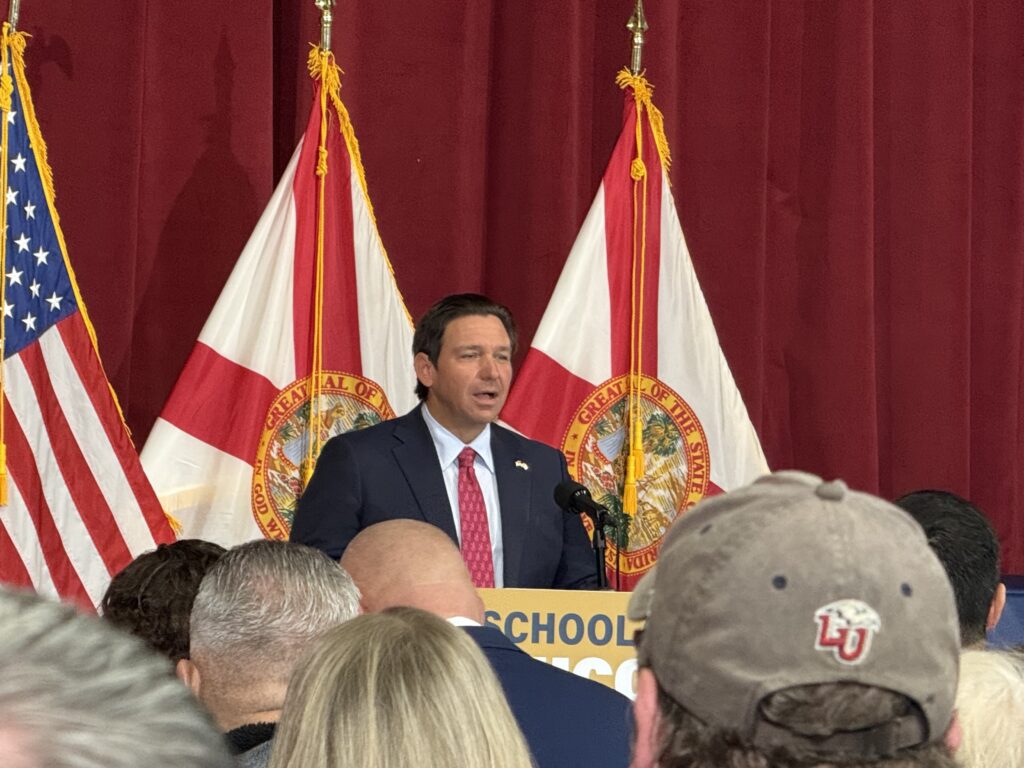

VALRICO – Gov. Ron DeSantis announced Wednesday morning that Florida will opt in to the nationwide Federal Scholarship Tax Credit program established in August by the Trump Administration.

The federal program, which will launch in 2027, is designed to bring education choice to families across the country. In doing so, it will give families from coast to coast what those in Florida have enjoyed for more than 20 years – the final word in the education of their children.

“The great stuff we're doing here probably is going to be pretty groundbreaking in states that have not yet gone down the road of school choice,” DeSantis said. “But here we are, further empowering residents and families to be able to make the most around the country.”

The federal program allows individual taxpayers to contribute to approved scholarship granting organizations, enabling students from a wide range of backgrounds to pursue the learning environment and educational resources that best fit their needs. Students in both public and private schools will benefit from resources that support tuition, tutoring, educational tools, technology, and special academic programs.

Step Up For Students, the Florida non-profit that manages the state’s education choice programs, will participate in administering the federal program by establishing the Step Up, Step Further Scholarship Fund, a separate 501c3 non-profit.

DeSantis made the announcement at Grace Christian School in Valrico as part of National School Choice Week. The school has 682 students on a Florida choice scholarship. The governor stood at the dais behind a sign that read, “School Choice Success. Florida is leading the nation.”

Anastasios Kamoutsas, Florida’s Commissioner of Education, followed DeSantis to the dais and said more than 1.4 million students in Florida benefit from a school choice option. More than 500,000 students receive one of the education choice scholarships.

DeSantis mentioned that Florida was the pioneer in education choice scholarships for students with unique abilities and for families who want to homeschool.

“Where do we rank in homeschooling? Do you know? At the top,” DeSantis said. “So we do good in homeschool because we embrace it and we empower.”

Kamoutsas said the purpose of National School Choice Week is to celebrate the freedom and opportunities that come with it.

“In Florida, that principle guides all that we do, and our students are better off because of it,” he said. “This week has been a time to showcase Florida's leadership in building the largest and most comprehensive school choice program in the nation.”