Denise Lever with her students at Baker Creek Academy, a tutoring center in Eagar, Arizona. Photo provided by Denise Lever

Nothing can stop Denise Lever. Not a raging wildfire and certainly not a state fire marshal’s effort to shut down her tutoring center by trying to impose regulations that could have forced her to spend $70,000 on building upgrades.

As one of the nation’s few female wildland firefighters in the late 1980s, Lever survived the hazing that came with being a woman in a male-dominated profession by proving herself and never backing down.

For example, take this story: Lever’s team had been dispatched to a California fire. Roads were closed, and the crew had to climb up a cliff to get into position. Loaded down with their gear, they pulled together and worked through the night.

“It was absolutely brutal,” Lever recalled. “It was hot. It was windy. Our hands were cut up from moving brush, and we lost gloves in the middle of the night, and we couldn’t find them on the fire line because of the debris.

As morning broke and a cold Pacific Ocean breeze stung their faces, the team huddled together in space blankets and reflected on their victory.

“The camaraderie and the sense of accomplishment, they’re irreplaceable,” Lever said.

Lever’s days of battling blazes ended when she got married and became a homeschool mom to three kids, but her trailblazing spirit stayed with her when she became an education entrepreneur.

In 2020, she opened Baker Creek Academy, a tutoring center/microschool to support homeschool families in Eagar, Arizona, just west of the New Mexico state line. The center operates four days a week for five hours per day and serves about 50 students, who attend on different days at various times. Baker Creek provides a host of supplemental services, primarily to homeschooled students, from one-on-one tutoring to limited classroom instruction and group projects to field trips. Students and parents can customize the services that best fit their needs. Baker Creek doesn’t keep attendance records because, Lever said, parents are the ones in charge.

After completing her city’s approval process, Baker Creek began operating in a historic commercial building once occupied by a church, shared with three other independent microschools.

One day, out of the blue, an official at the Arizona Office of the State Fire Marshal left Lever a voice mail message. He wanted to inspect her “school.”

“And I said, ‘No, not really, because we're not a school,’” she said.

As an experienced firefighter, Lever recognized a school designation for what it was: the potential kiss of death for her tutoring center.

Being labeled a school triggers a list of code restrictions intended for campuses that serve hundreds or sometimes thousands of students and often include sports fields, playgrounds, auditoriums, cafeterias, gymnasiums, classrooms, and offices.

On the line are often tens of thousands of dollars in mandated building changes, which are not required for other commercial buildings, such as dance studios and karate dojos.

Levers wasted no time. She contacted the Stand Together Edupreneur Resource Center, which offers guidance, but not legal advice, about regulatory issues. The representative encouraged Lever to contact the Institute for Justice, a national public interest law firm that specializes in education choice litigation and zoning issues.

IJ Senior Attorney Erica Smith Ewing sent a letter to the state’s fire inspector questioning the basis for the inspection.

“Ms. Lever successfully completed a local fire safety inspection in 2023 and has been operating successfully with no problems,” the letter said. “Your request to inspect her property was unexpected. Could you please explain why you wish to inspect her property? We do not currently represent Ms. Lever, and we hope that formal representation will be unnecessary.”

Lever said she faced the possibility of having to spend tens of thousands of dollars upgrading doors and electrical systems. Because the building was smaller than 10,000 square feet, she avoided the order to install a sprinkler system, which can cost $100,000.

However, the timing couldn’t have been worse.

“If the state was going to require some of these upgrades, that was just not going to be possible for (our landlord) to renew our lease,” she said, adding that she used the building to host summer programs and annual meetings for other microschool leaders who use her consulting services.

Lever also wondered why similar businesses weren’t targeted -- for example, a dance studio across the street that taught school-age students and operated similar hours to Baker Creek.

“Because she offered dance instead of math tutoring, her program was considered a trade, and our program was going to be shut down and treated like an education facility simply because we offered more of an academic program,” Lever said.

State officials performed the inspection, but finally backed down, offering only that the situation was a result of “confusion” and the Lever’s business wasn’t under their jurisdiction.

“Forcing Denise to follow regulations designed for sprawling, traditional schools would be both arbitrary and unconstitutional,” Ewing said. “More and more, we are seeing state and local governments hampering small, innovative microschools by forcing them into fire, zoning, and building regulations that never anticipated microschools and that make no sense being applied to what microschools do.”

In Georgia, local officials tried to force a microschool to comply with unnecessary inspections and building upgrades, in violation of state law protecting microschools. They backed down after a letter from IJ. And in Sarasota, Florida, Alison Rini, founder of Star Lab, nearly closed her doors this spring when the city interpreted the fire code to require she install a $100,000 fire sprinkler system, despite operating from a one-room building with multiple exits. Only after a donor provided a generous gift was she able to stay open.

“Teachers shouldn’t need lawyers to teach,” said IJ Attorney Mike Greenberg. “Bureaucrats shouldn’t use outdated and ill-fitting regulations to stifle parents and students from choosing the innovative education options that best suit their needs.”

Lever said the state’s decision to back off sets a precedent that will help other microschools across Arizona.

“I was definitely willing to go forth with the lawsuit,” she said. “At this point, though, we’re going to take our win. We’re going to publicize it so the other microschools will know what their options are.”

EdChoice has an interesting survey question comparing what sort of school parents would prefer (district, charter, private or home) and comparing the results to actual enrollment patterns. In 2024 it looked like this:

There is a lot happening in that chart, starting with the apparent desire of approximately 50% of the parents of district students to have their students somewhere else. Of course, a great many legal and practical constraints stand between preference and reality, which is why we have an education freedom movement and why we find so much opposition from the insecure K-12 reactionary community. Taking the surveyed demand as a part of a thought experiment around “what would it take to give families what they want?” can be illuminating. Of course, in the real world, these things change only gradually. Arizona has the highest percentage of students in charter schools at 21% or so, but it took three decades to get there for all kinds of reasons, including the need to have school space, which involved a great deal of construction and debt. We live in a world of charter and private school scarcity relative to demand, and keeping up the previous (inadequate) pace of construction may prove difficult.

Using my advanced skills acquired in the Texas public school system between 1972 and 1986, I have used this surveyed demand to calculate an implied demand for an additional 1.1 million charter school spaces. Don’t hold your breath waiting for them. It took almost three and a half decades to reach 3.7 million, and if you’ll now take a look at the first chart above, you’ll see that most of that three-and-a-half-decade period involved relatively low and almost continually declining long term interest rates between 1991 and 2021.

After 2021, both interest and building costs went up for charter school construction. Interest rates of course could go down, but they could also (gulp) go further up. A slowdown in the rate of new charter openings happened before the increase in interest and construction costs:

The little green force mystic taught us “always uncertain the future is,” but it appears to me that circumstances will require the rise of different school models that create seats sans debt. The old expression holds that God doesn’t close a door without opening a window, and the recent rise in interest rates happened almost simultaneously with the rise of pandemic pods and a la carte learning.

Star Lab students learn through creative activities like this fishing game. Photo courtesy of Star Lab.

SARASOTA, Fla. – Alison Rini thought her destiny was to be the principal at a traditional public school. She had been the principal at a charter school, the assistant principal at a Title I district school, and the assistant principal at a magnet school for gifted students.

But in the wake of Covid, Rini began to feel “adrift.” The system, in her view, proved incapable of helping students, particularly low-income students, overcome the academic and behavioral deficits left by distance learning. Some students were being promoted, even though they weren’t ready. Others were being labelled disabled, even though they weren’t.

“My path wasn’t leading to where I thought it would,” Rini said. “It felt like they just wanted me to grease the wheels to keep them turning. And people were getting chopped up in the gears.”

“I just felt there’s got to be a better way.”

In 2023, Rini took a leap of faith, one that is becoming common for public school teachers in school-choice-rich states like Florida.

She decided to start her own school.

For other recent examples, see here, here, here, here, and here.

With help from The Drexel Fund, a philanthropy that helps promising new private schools start and/or grow, Rini took a year to plan. She visited successful schools across the country; acquired deeper knowledge about the business side of running a school; and mapped out exactly what she wanted to create. Her vision was based on 20-plus years of learning the best approaches from teaching in all types of schools, from New York City to the Virgin Islands to the Gulf Coast of Florida.

The result is Star Lab, a private microschool that opened last fall with a handful of kindergartners and is now set to expand. It’s housed in the recreation center of an oak-graced public housing complex in Newtown, a historic Black neighborhood in Sarasota.

Watching students walk up on the first day of school in their Star Lab shirts was “an out of body experience,” Rini said.

“It was just such a dream come true,” she said. “And this year has been such a joy, to behold the power of just tailoring something around kids – not around adults, not around the system.”

Star Lab is a rich blend of philosophies and practices that reflect Rini’s background in education and neuroscience. (Rini earned a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience and behavior, and master’s degrees in elementary education and education leadership, all from Columbia.)

Star Lab’s approach to reading instruction is grounded in “science of reading” research. It employes hands-on Montessori materials to help students better grasp some academic concepts at their own pace. It embraces the Finnish approach to student movement, which sees frequent play breaks as optimal for learning. It also emphasizes individualized lessons, mastery learning, lots of direct instruction, and progress monitoring via a custom-built dashboard.

“We're not just educating,” the school website says, “we're preparing future leaders, innovators, and global citizens who are as healthy and mindful as they are intellectually empowered.”

Exercise and mindfulness are an important part fo the daily routine at Star Lab. Photo courtesy of Star Lab

Every morning at Star Lab starts with 25 minutes of exercise and five minutes of “mindfulness” activities. Monday through Thursday, the students are immersed in core academics. Fridays are for group activities like drama, field trips, and guest speakers.

Rini guarantees parents that Star Lab students will perform at or above grade level in reading and math. Most of the students in the neighborhood are not at that level, which is why Rini chose to be here. According to the most recent state stats, 38% of Black students in Sarasota County are reading at grade level, compared to 68% of White students.

“I just felt drawn to it,” Rini said of Newtown. “Super wealthy people already have school choice.” But all families deserve the ability to choose, Rini continued.

Every student at Star Lab uses a state choice scholarship and there are no other fees.

Rini could be a poster child for the wave of education entrepreneurs who are rising in Florida and other choice-rich states – both for the promise they represent, and the pitfalls they continue to face.

Due to fire-code complications, Star Lab could only serve five students this year. Rini didn’t learn about the snag until two weeks before school opened, and the remedy – a $97,000 sprinkler system – wasn’t financially possible. A local philanthropy recently stepped forward to help the housing authority pay for the sprinkler system. But Rini’s case isn’t an isolated one, as stories like this one and reports like this one highlight.

With the stars finally lined up at Star Lab, 14 students have already enrolled for this fall, and more are expected.

The draws are many.

For families who live in the complex, the school couldn’t be more convenient. The individual attention is tough to match. (Besides Rini, there’s another teacher and an assistant.) And it’s clear the school is enmeshed in the community.

Last month, the school hosted a “design lab” with local college professors and more than a dozen parents in the neighborhood, so the parents could discuss the educational needs of their children and how they could be better met. A few days later, Star Lab students built a float for the Newtown Easter Parade. In early May, the school hosted an international food festival for the neighborhood, so the students, their families, and their neighbors could, in Rini’s words, “travel the world through their taste buds.”

It’s not just families who are benefiting from the emergence of distinctive new schools like Star Lab.

“If you are not happy at your job, I would say don’t accept that as your fate,” Rini said, referring to other educators. “There are options, and some of them are already out there. And some of them don’t exist yet, but they might be in your head or in your heart.”

With choice, they don’t have to stay there.

Growing up, Adam Tweet loved learning. Until he didn’t.

Kindergarten was amazing, but as he got older, Adam wanted the freedom to pursue things he enjoyed. He loved reading but not books typically found on school reading lists. Comic books and interactive Choose Your Own Adventure books fed his passions.

But teachers told him he couldn’t read those books, even if they sat on school library shelves. He needed to read what they assigned.

“And that just turned me off reading,” Adam said. Now, the former Florida public school teacher and administrator wants to offer a learning environment for kids who were like him, who chafed under rigid rules and found joy by pursuing their passions, which for Adam included soccer and ice hockey.

Adam is one of 50 people across the United States chosen to be part of Primer Microschools’ inaugural Leader Fellowship program.  Likened to an evening MBA program, its goal is to help participants open and run Primer Microschools in their communities. Adam is among 28 fellows across Florida, where universal eligibility for education savings accounts has created a supercharged environment that allows the state to celebrate National School Choice Week with gusto.

Likened to an evening MBA program, its goal is to help participants open and run Primer Microschools in their communities. Adam is among 28 fellows across Florida, where universal eligibility for education savings accounts has created a supercharged environment that allows the state to celebrate National School Choice Week with gusto.

A Minnesota native and self-described “average student,” Adam majored in P.E. and health. After graduation, he found few opportunities to teach those subjects. He fell into elementary school teaching after RCMA Immokalee Community Academy, a Florida charter school that serves primarily migrant farm working families, turned him down for the P.E. job but offered him a position teaching third grade. That started an education career that spanned more than a decade, including a year in Brooklyn, New York, and eight years in administrative roles for the School District of Lee County in Florida.

Then he became a parent, and his perspective changed.

“I was going on with my career and I’m like, ‘Public schools, public schools, I love them,’” he recalled. “And then I had my daughter, and it kind of switched.”

Adam and his wife, Paloma, wanted to examine every option to find the best education for their daughter, Harper, who is now 4 and in voluntary pre-kindergarten.

That exploration included research into microschools, which are intentionally small, teacher-led learning environments. They have been called a modern version of 19th-century one-room schoolhouses.

Florida has a plethora of such schools, including Kind Academy of Coral Springs, which began in 2016 and offers full-time and hybrid homeschool programs. Kind’s founder, Iman Alleyne, started her own 10-week training program for aspiring founders in 2022, with a goal of opening 100 microschools in 10 years. About a half-hour south in Davie, Colossal Academy offers middle school students the chance to spend part of their time on a farm. Partnerships with other nearby providers such as Surf Skate Science, which provides a hands-on approach to learning math, science, and design through the pursuits of surfing and skateboarding. Acton Academy has also brought its brand of student-directed learning to Florida, with 15 schools that put students on a “heroes’ journey.”

The National Microschooling Center estimates 95,000 microschools across the United States served more than 1 million students last year. With the passage or expansion of education savings accounts, microschools are expected to grow more in 2025.

When Adam and Paloma discovered Primer Microschools, they liked what they saw: competency-based learning with no age-based groups and with dedicated time for students to pursue passion projects that can range from setting up an art gallery to making and selling lip gloss. As a former P.E. teacher, Adam also liked the emphasis on outdoor activities.

Adam could also relate to Primer founder Ryan Delk’s story growing up as a homeschooler in central Florida. Delk’s mom, a teacher, wasn’t satisfied with the low-rated zoned school after moving to his grandparents’ home in 1996. So, she started a small homeschool for him, his siblings, and a few neighborhood kids. Rather than relying on textbooks, Delk’s mom made learning an adventure. She took them on field trips to historic sites to learn about the American Revolution and created a network of cardboard tunnels for students to crawl through to learn how the human digestive system works.

Adam wanted that experience for his daughter. And himself. Last summer, while his car was being serviced, he decided on a whim to fire off a text to Delk asking about the launch of a new fellowship program to help teachers start their own Primer Microschools.

To his surprise, Delk responded immediately.

“We talked for about 10 to 15 minutes,” while the mechanics worked on his car, Adam said.

Delk was moved by Adam’s sharing his sadness at watching once wide-eyed kids gradually lose their love for learning as they progressed through the traditional model and invited him to apply for the fellowship program.

“I really believed in what he was doing,” Adam said. “Academics are certainly important. Mastering reading, mastering math. But their project-based learning is amazing. Behavior problems are non-existent. Engagement is through the roof.”

Adam applied and was accepted. Primer is funding the program with a $1 million Yass Prize last year and is working to scale its established networks beyond South Florida and Arizona, and into new locations throughout Florida — from the Gulf Coast to the Panhandle — and into Alabama.

Fellows attend weekly live virtual training and work toward key milestones, such as finding a location. A new Florida law that Delk helped get passed last year eases certain zoning rules for those opening in locations such as religious buildings, libraries, community centers, former schools, and even theaters.

Fellows also receive a $500 monthly stipend. Training is held during the evenings to enable participants to continue their day jobs.

When they open their schools in August, they will become Primer employees and receive a salary and benefits.

Adam, who has enrolled his daughter for next year, plans to start his school in Fort Myers. His goal is to enroll 45 students, with three groups, one for kindergarten through second grade, another for grades three through five, and a third for grades six through eight. His school, like other Primer Microschools, accepts state school choice scholarships. Primer also works with qualified families to secure other need-based financial aid.

Now, Adam and the other fellows are working hard to prepare. They are learning from Primer leaders about the school’s proprietary software, its instructional methods, how to recruit students and navigate real estate matters.

Adam said the software program is “very user-friendly” and allows parents to keep track of what their kids are working on and their daily progress. The best thing, however, is being able to ask questions, share ideas, and celebrate wins with other fellows through a Slack group.

“Having the community of Primer has been incredible,” Adam said. “I don’t feel like I’m doing it alone.”

He looks forward to being able to “help other families in our community whose kids are similar to mine – they have passions but where they’re at now is not meeting those passions.”

Adam said he is working to finalize a location and anticipates an August opening.

Mornings will be devoted to core academics, while each afternoon, students will have an opportunity to pursue dreams that could include learning to code, creating podcasts, baking cakes or writing songs.

Adam’s classroom will be well stocked with reading materials, including lots of Choose Your Own Adventure and comic books.

Years ago, I was getting what remained of my hair cut in Prescott, Arizona. My barber was telling me about the old days in Arizona, and that he had grown up in the old mining town of Jerome (once known as “the most Wicked Town in the West”) before the town died in the 1950s when the massive copper mine closed. He told me that as a young man he had assisted his older brother in tearing down four abandoned homes and hauling the lumber down the mountain to build a house and a barn, where his brother still lived. The barber asked me “Do you know how hard it was to get the permits to do that?” I responded, “No sir, how hard was it?” He replied:

It wasn’t hard at all; we didn’t need a permit back in those days. In those days we were free!

Can we live free these days? In 2018, I wrote an introductory post as executive editor of this blog, which concluded as follows:

Funding for public education is guaranteed in the Florida Constitution and is as close to a permanent institution as you get in American society. It’s here to stay. Florida, however, has the chance not just to practice the form of public education, but to fulfill its actual promise. Much divides our society, but Americans still unite on crucial issues, including education. We desperately want an education system that gives students the knowledge, skills and habits needed for success and to responsibly exercise democratic citizenship. We – left, right and center – commonly and fiercely desire a system of schooling which serves as an engine of class mobility. Florida has moved the needle in this direction by setting families free to pursue opportunities that would otherwise be denied to them. More of this is needed and the next step will be to develop a consensus around setting educators free as well.

More on that later.

Grim challenges lie ahead for Florida. I’ll lay out the latest on some of them in coming posts. We should never, however, make the mistake of underestimating human ingenuity – and especially of betting against a wildly inventive state in the world’s most creative nation. Your challenges will be great, but you have been more than equal to them thus far.

Go and amaze us. Where Florida leads, others will follow.

A recent article in Politicio called 'Microschools' could be the next big school choice push. Florida is on the cutting edge made it clear that over the past six years Florida has done a great deal to free teachers to create and control their own schools to pursue their vision of a high-quality education. This is incredibly exciting, but great promise and peril lie ahead. From the Politicio article:

Florida appears to be one of the few states so far to ease restrictions for private schools, joining Utah in passing a law that clears a path for more microschools — a move opponents fear strips power from local communities.

While Florida's law doesn’t explicitly address microschooling, the new policy permits private schools to use facilities owned or leased by a library, community service organization, museum, performing arts venue, theater, cinema or church under the property’s current zoning and land-use designations. The private school does not have to pursue any rezoning or seek a special exception or land-use change to operate in those spaces.

Now, I live thousands of miles away from Florida in a distant and pleasant patch of cactus. I am, however, willing to wager that, sadly, Florida probably is not immune from the phenomenon of petty little dictators. The “little Platoons” that de Tocqueville wrote so approvingly of find themselves hamstrung today by the need for traffic studies and HOA regulations.

A golden age of schools controlled by Florida teachers and shaped by the voluntary associations of Florida families beckons. The same reason many of us find this exciting, others will see it as terrifying: because it is outside the control of control freaks. Bossy McBossypants and Petty L. Tyrants of various sorts will not be pleased. All the better in my view. Give them something to cry about.

Politicio certainly has this right: Florida is on the leading edge. I will simply reiterate to my Florida friends: Go forth and amaze us. Where Florida leads, others will follow.

Go down, Moses

Way down in Egypt's land

Tell old Pharaoh

Let my people go

The Texas House of Representatives closed out the 3rd special session by filing a deeply flawed ESA bill but never held a hearing on it. Stay tuned for further developments. Meanwhile, the Texas Tribune filed a fantastic piece featuring three Dallas Black mothers who support a choice program in order to allow themselves and others in their communities to run and sustain their own schools. This is an amazing piece of journalism that looks past spokespeople with dueling sets of talking points in Austin to talk to real people and explore their concerns. You should read it and share it widely.

An earlier post on this blog described the era of peonage, whereby private interests availed themselves of convict labor at below-market rates. Described by some as “neo-slavery” this was a morally repugnant institution but one which benefited powerful interests. It lasted far longer than it should have, but eventually earned a well-deserved spot in the dustbin of history.

The parallel here is not to public schooling per se but rather to ZIP code assignment. ZIP code assignment to schools effectively reduces children into indentured funding units. Powerful interests in today’s society financially benefit reducing children into indentured funding units. Like southern plantation owners and railroad magnates from a bygone era, they are not going to let peonage go away without a fight.

The Tribune piece can be understood in this light: a struggle for a more humane system, one that acknowledges and respects the need for pluralism and variety in schooling. My heart sang when the story of these heroic women included a description of the aid they had received from their fellows in Arizona:

"In Arizona, 40 Black moms gathered in 2016 with the same worries for their children, ready to dismantle what they call the school-to-prison pipeline. Their kids were bullied in school and did not feel supported by the teachers. The moms started by pushing school districts to form a re-entry-after-suspension plan and find alternatives to suspension as a disciplinary measure.

By 2021, they had opened their own microschool, also known as outsourced home schooling. The Arizona microschools depend on the state’s education savings account program for sustainability.

“The public school system that was in place was not doing what it was supposed to do. Our children were not reaping the benefits,” said Janelle Wood, the founder of Black Mothers Forum in Arizona. “And so we needed a tool to help us fuel our vehicle of the microschool in order for us to grow."

Choice provides families with the tools to chart their own path and determine their own future. It gives teachers like those featured in the Tribune the opportunity to create their own schools. Choice gives families the opportunity to find a school that is a good fit for their children. Texas legislators must decide between clinging to an antiquated past or embracing a brighter future.

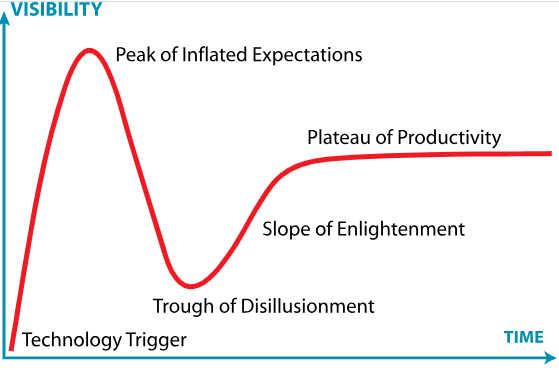

If there was any doubt about where microschools currently stand in the hype cycle, critics on the left are now being joined by worriers on the right.

Daniel Buck of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute recently reflected on his visit to a conference hosted by Harvard University that highlighted the rise of microschools and other learning environments that defy the conventions of schooling.

He describes seeing "much to love" about these small independent learning communities, but also notes a troubling "ideological undercurrent" among many of the educators who animate it, including an infatuation with progressive and student-led pedagogies.

In a compelling piece a few months ago in these pages, veteran homeschooling mom Larissa Phillips details the movement’s infatuation with unschooling, a theory of education (if we could call it that) that postulates that, if we just let kids be, they’ll follow their own passions to success. She details parents arguing about whether kids should be expected to follow basic rules, attend classes that they don’t like, or bother getting out of bed if they didn’t feel like it that day.

. Inquiry learning, project-based learning, self-directed learning, and other models of a similar stripe abound. The center’s founder argues that this preference for self-direction is inherent in the model’s rejection of systematization. In an interview with the New York Times, Jerry Mintz, the founder of Alternative Education Resource Organization, an institution that supports microschools and independent schools, shares a similar sentiment: “Kids are natural learners, and the job of the educator is to help kids find resources; they are more guides than teachers.”

Color me skeptical.

The philosophy drawing Buck's skepticism was famously summed up by Plutarch: "The mind is not a vessel that needs filling, but wood that needs igniting."

There's a reason this kind of thinking takes root among microschools, homeschoolers, and others operating outside the public education system.

If the past 200 years of American public education were a battle between the vessel-fillers and the fire-igniters, the vessel-fillers have won in a rout. Compulsory schooling laws, accountability systems tied to standardized tests, and a grammar of schooling that assumes teachers lead classes of students with desks lined up in rows are all victories of the bucket-fillers.

The fire-lighters have been pushed to the margins, where they wage a guerilla campaign that waxes and wanes over decades. The last great insurgency came during the '60s and '70s, when the "freed school" movement spawned a proliferation of small independent learning communities across the country.

Scholars who documented free schools noted they appeared to have two major flavors: One led by hippy types committed to progressive student-directed pedagogies, the other led by African Americans who critiqued a public education system that they felt mistreated their children. The former were committed fire-lighters; the latter were more amenable to vessel-filling.

The freedom school movement died off over the past few decades (though a few live on). Both its major strands are present in the new wave of microschools, hybrid homeschools, and other small learning communities operating outside public education that has gained momentum after the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the current wave includes other ideological currents, some of which conservatives like Buck will likely find more amenable, like commitments to religious instruction or classical education.

A crude account of the appeal of classical education is that it critiques public education from the direction opposite the progressive fire-lighters, arguing conventional schools fail to instill virtue in young people or fill their vessels with sufficient knowledge of the great cultural works of Western civilization.

In short, the educational philosophies animating the current microschool movement are all over the ideological and pedagogical spectrum. But they have one important thing common: They reject some of the prevailing norms in public education. They are intentionally creating models that are, in some way, different.

So, while Buck makes important points about the need for educators operating in permissionless learning environments to continually examine their methods and improve their practice, it's also essential to recognize that the movement is likely never to reach consensus on some fundamental beliefs about what education ought to look like. That's a feature, not a bug.

Microschools have been having a moment, garnering positive headlines in the Christian Science Monitor, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post and other mainstream outlets. They're one of the hottest topics on social media and the education conference circuit.

So it's no surprise the inevitable backlash is brewing.

Before we get into it, I'd like to make one stipulation. The term "microschools" defies tidy definitions.

Often, but not always, microschools are smaller than typical learning environments. Often, but not always, they operate outside the aegis of the public school system. Sometimes, but not always, they rely on adults who don't hold traditional teaching credentials. Sometimes, but not always, they blur the lines between schooling and homeschooling, hosting students around living room tables or on farms or in the woods.

Two different people may use the term microschool and have completely different learning environments in mind. Neither would necessarily be wrong.

Now for the backlash, via education blogger Peter Greene.

When someone asks hard critiques like "This voucher you're offering me won't cover the cost of any private school" or "When this voucher program guts public school funding, families in our rural area will have no choices at all" then microschools are the handy choicer answer.

Can't get your kid into a nice private school with your voucher? Well, you can still pool resources with a couple of neighbors, buy some hardware, license some software, and start your own microschool! Microschools allow choicers to argue that nobody will be left behind in a choice landscape, that vouchers will not simply be an education entitlement for the wealthy. (Spoiler alert: the wealthy will not be pulling their children out of private schools so they can microschool instead).

In other words, microschools do not solve any educational problems. They solve a policy argument problem. They do not offer new and better ways to educate children. They offer new ways to argue in favor of vouchers. Well, all that and they also offer a way for edupreneurs to cash in on the education privatization movement.

Greene is right about one thing. Often, but not always, microschools aren't competing with elite private schools. It's a safe bet that most parents shelling out upwards of $30,000 a year for tuition are not about to abandon their exclusive cloisters for a repurposed farmhouse that charges a few hundred bucks per month. Recent reports by the VELA Education Fund on community-created learning environments (which sometimes, but not always, take the form of microschools) and the National Microschooling Center suggest that the typical microschool family is decidedly middle class. These are families who could never contemplate the likes Andover or Gulliver Prep. They might be able to scrape together modest tuition payments, but an $8,000-per-year scholarship could make a big difference in what they can afford.

I'm on the record as a pre-pandemic microschool enthusiast and spent time during the pandemic studying learning pods (which often, but not always, shared many features with microschools). So, I'd like to offer a response to Greene's question, which recalls the technological skepticism of Neil Postman: What is the problem to which microschools are the solution? And whose problem is it?

For pandemic pods, the answer was simple. Schools shut down, and families needed a place their kids could go.

But many families discovered other benefits they weren't getting in conventional schools. Teachers could be more flexible with their time, and therefore, more responsive to the needs of their students. Students enjoyed more humane learning environments in big and small ways. Children with disabilities received more individual attention. Students could freely grab a snack when they wanted. Community assets, from the neighbor with a knack for carpentry to the museums and community groups previously confined to afterschool programs, could play a more central part in the schooling experience. Adults from more diverse backgrounds, like parents or community volunteers who loved working with kids but lacked a teaching certificate, found new opportunities to share their passions. And the small size allowed for a far wider array of diverse options catering to families' unique preferences than were typically possible.

Many parents abandoned their podding experiences once schools reopened. Conventional schools still offered countless advantages (a large and diverse group of peers, guaranteed childcare outside the home, reliable special education services, no out-of-pocket costs).

But other families latched on to the growing array of microschools that, at least for the educators who created them or the families who used them, solve any number of the problems plaguing public education: youth mental health is in crisis, teacher morale is flagging, voluntary community associations are desiccated, students are often disengaged if they're showing up at all, bonds of trust between schools and families are fraying.

It takes a special kind of cynic to imagine the current blossoming of small learning environments where teachers are free to realize their peculiar vision for what learning could look like and partner with families to make it happen is the brainchild of a few voucher advocates. Notably, most of the learning environments catalogued by Vela say they don't access public funding at all.

And it's no surprise legions of researchers, journalists, advocates and program officers at education foundations have all latched on to microschools at the same time. They see previous education reform fads (teacher evaluations, personalized learning) sucking wind. They're peering desperately for beams of light amid the post-pandemic gloom. And when they actually visit microschools or talk to educators who work in them, they see what I've seen: The kids are happy. The teachers are energized. Families and community groups, often sidelined in schools, are pulled into the center of the learning experience. If you ask a student what they're doing and why, they’ll tell you, often enthusiastically. These are things we should hope to find in any learning environment. The fact that they stand out underscores the extent of the current malaise.

If microschools are following Gartner's hype cycle, they're probably coasting somewhere between the peak of inflated expectations and the trough of disillusionment.

Gartner's Hype Cycle (via Wikimedia Commons)

To reach the plateau of productivity, they're going to have to grapple with questions about financial stability and methods for reporting student outcomes. They'll need to devise new ways to provide special education services, transportation, and other essential infrastructure that ensures they're accessible to all students.

But I'm willing to bet that anyone who actually visited these learning environments, or spoke to the educators who worked there, would come away with their cynicism punctured and a belief that these bottom-up efforts are getting so much attention precisely because they're positing novel solutions to countless different problems facing young people and public education.

When it comes to education, a rising tide lifts all boats, Florida’s education commissioner told a national audience of school choice supporters and education entrepreneurs.

Look at Miami-Dade County, where leaders saw the tsunami coming and grabbed their surfboards.

“The district figured out that movement in South Florida was coming so fast and becoming so popular that the only way they could survive was to improve their services, (and) to improve their offerings,” Manny Diaz Jr. told those attending a conference sponsored by Harvard University called “Emerging School Models: Moving from Alternative to Mainstream.”

Despite the dire warnings that opponents have repeatedly issued since Gov. Jeb Bush and Florida lawmakers first began stirring up that school choice wave in 1999, none of the predicted devastation has come true, Diaz said.

Now, 70% of students in Miami-Dade attend a school of choice in the nation’s third-largest public school district. Those include charters, magnets, public schools with open enrollment policies and specialty academies, as well as the nation’s largest education choice scholarship programs.

Such a win-win situation didn’t stop the teachers unions and other school choice opponents from sounding the same alarms when he sponsored education choice legislation as a state senator.

“When we passed House Bill 1, they said the sky was going to fall,” Diaz said. “They were completely wrong.”

Over more than two decades, the legislation has created new options, including multiple scholarships with different funding sources that serve students with a variety of needs.

HB 1 was the latest advance. Signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis in 2023, it granted scholarship eligibility to all families regardless of income and converted all traditional private school scholarship programs to education savings accounts. The change allows parents the flexibility to spend their student’s allocation on tuition and fees, curriculum, part-time tutoring, and other approved expenses.

Diaz said the key to Florida’s success is its continuous quest for improvement, which at times has involved the passage of new expansions each year.

“It is a relentless chase of continuing to push,” he said. “The best defense is to be continually on offense.”

Local zoning codes often create hurdles for entrepreneurs such as Tia Howard, center, who wants to open a microschool in a rural area near Mesa, Arizona. Photo courtesy of the Institute For Justice

In Arizona, an education entrepreneur can’t open her microshool because of zoning codes that bar private schools, but not public schools, from operating in residential areas.

In Nevada, a retired Navy officer and engineer who holds two college degrees is being told he can’t open a secular private school because state occupational license rules require a teaching degree or a teacher or administrator license but exempt religious schools.

“It’s all super arbitrary,” said Jon England, education policy analyst at Libertas Institute, a Utah libertarian think tank that supports rule changes to make it easier for new forms of education to flourish.

England has heard it all, from rules that classify private schools as businesses and limit their ability to locate in certain areas, only to apply stricter school occupancy requirements when they try to open in locations built for businesses, as well as and those that allow religious instruction but bar secular education in the same building.

“So, 10 kids can go to Sunday school, but teach a math class to the same 10 kids, and you’ve now violated occupancy,” he said. “It’s silly things.”

England met last year with a dozen education entrepreneurs who cited zoning and occupancy rules as their biggest hurdles.

One of them, Paul Tanner, shared the back-and-forth he endured with city officials before being allowed to open his school, Choice Academy. He initially wanted to open his school in a residential area, but city officials told him that he was a private business, which zoning did now allow there. He found another location at a small office building, only to have city officials inspect the building as if it were a school and apply stricter rules.

Despite the demand for alternatives to traditional education sparked by many state legislatures’ recent establishment or expansion of education choice, England said school founders have found little relief from barriers put up by local governments.

“It’s still a big issue,” said England, who thinks the number of discouraged entrepreneurs is greater than people think. “A lot of those we talked to are the ones who fought and kept going. I have no idea how many started and ran into so many barriers and said it’s not worth it and gave up.”

Though startups have made most of the headlines lately, they aren’t the only ones encountering stumbling blocks put up by local governments.

Traditional private schools, which were not always included in relief legislation passed for charter schools, still must struggle with zoning and occupancy codes that can require costly renovations.

Steve Hicks, chief operating officer for Center Academy, which operates 11 Florida college prep schools for students with learning differences, said he had to overcome many obstacles over the years. He recalled easily opening a school, only to have the fire marshal come back a year later and require adjustments to doors because new fire codes prohibited doors that opened into hallways.

The school had to spend $25,000 to recess all the doors. At another school, he had to raise the floor 21 inches soon after moving in because the floodplain maps had changed.

Still, Hicks said some local government rules are critical to health and safety. However, he said he sees no reason that private schools shouldn’t be provided the same land-use exemptions that Florida charter schools receive and that were extended last year to private -tutoring centers serving up to 25 students.

“Not all private schools can go buy 20 acres of property to build their schools,” he said.

England said education choice supporters backed a bill last year that would have granted the same relief to privately run microschools that Utah charter schools received a decade ago. That legislation allowed charter schools in every zone, though cities can require setbacks, traffic studies and other conditions. The microschool version failed to pass the Senate, but supportive lawmakers plan to bring it up again when the legislative session begins in January.

Passage would put Utah’s policies on par with Wyoming, which in 2019 passed a law requiring local governments to apply the same rules for public school zonings to private schools.

The State Policy Network has also put out a report on ways states can encourage education entrepreneurship. Recommendations include easing zoning restrictions and creating “innovation tracks” for licensing.

As founders in states that lack relief wait on reforms, some, like Tia Howard of Arizona, are receiving help from the Institute for Justice, a public-interest law firm that defends education choice policies and education entrepreneurs. Institute attorneys recently sent a letter asking Pinal County officials to allow her microschool in a rural area near Mesa or face a possible court challenge.

“We understand that most zoning regulations were written without regard to the existence of micro schools,” the letter said. “But micro schools are here now, and they are here to stay.”