The big story: After delivering a one-two punch to Blaine Amendments, the nation’s highest court decided not to take aim at Michigan’s version.

Zoom in: This week, the U.S. Supreme Court declined a request to hear an appeal of a 2021 lawsuit brought by kindergarten mom Jill Hile and four other families in the Wolverine State who sued after they were prohibited from using funds saved through the Michigan Education Savings Program, a tax-exempt 529 plan, to help offset the cost of K-12 private school tuition. The court offered no comment when it announced the decision, taken up during a Sept. 30 private conference preceding its 2024-25 term. The refusal to hear the case lets stand a Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals decision affirming a lower court’s ruling that upheld the constitutional ban on private school support.

The issue: A string of recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings has struck down provisions in other state constitutions that bar direct state  funding of private and religious schools. Michigan takes things to another level by prohibiting state funds from supporting any non-public educational institution. This, according to the Sixth Circuit, includes indirect aid like tax-exempt funds saved through 529 plans. This makes Michigan’s Blaine Amendment, enacted in 1970, among the most restrictive in the nation.

funding of private and religious schools. Michigan takes things to another level by prohibiting state funds from supporting any non-public educational institution. This, according to the Sixth Circuit, includes indirect aid like tax-exempt funds saved through 529 plans. This makes Michigan’s Blaine Amendment, enacted in 1970, among the most restrictive in the nation.

Other states, including Kentucky, have restrictive versions of the Blaine amendment. The Bluegrass State provision has shot down laws establishing private school scholarship programs as well as charter schools. Kentucky voters are set to go to the polls next month to decide whether they want to rewrite part of the state constitution to let the state legislature allocate taxpayer dollars to these educational opportunities.

Yes, but: The Supreme Court’s refusal to hear this case could open the door for other states to use Michigan’s overly broad Blaine Amendment as a blueprint to hinder school choice. However, some legal experts doubt that will happen.

“Politically, that would be an uphill battle in most states with parental choice programs,” said Nicole Stelle Garnett, a law professor and director of the Notre Dame Education Law Project. “It won't stop opponents from trying, of course.”

What they’re saying: “Michigan families are desperate to have more options,” said Molly Macek, director of education policy at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, which teamed up with a Michigan law firm to represent the families in the case. “A child’s educational success shouldn’t be determined by the family’s financial means or ZIP code. We will continue to keep fighting until every family has the ability to choose the best education for their children.”

Next steps: Burdensome rules make repealing Michigan’s Blaine amendment highly unlikely. A two-thirds majority of the state’s lawmakers would have to vote to remove it legislatively. Or supporters could try a ballot signature amendment that would require 446,197 signatures from registered voters to get the issue on the ballot. Another solution would be for Congress to pass a national education choice bill that would make Blaine amendments obsolete – or at least give families a way to bypass them.

Not a cure-all: Legal experts warned that landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions that struck down bans on religious schools from participating in choice programs wouldn’t be a panacea. “Despite the Supreme Court's decisions in Espinoza and Carson, barriers to educational choice remain in a small handful of states with "’public/private’" Blaine Amendments,” said Michael Bindas, a senior attorney of the Institute for Justice who argued the Carson case before the high court. “Although it is unfortunate that the Supreme Court did not use Hile v. Michigan as an opportunity to address the federal unconstitutionality of such provisions, we are confident that the Court will eventually do so.”

Growing pains: Blaine amendments were primarily rooted in bigotry aimed at the increasing numbers of Catholic immigrants entering the United States during the 1800s. Other laws required all students to attend district schools, which at the time promoted Protestantism. A 100-year-old landmark Supreme Court ruling in Pierce v. Society of Sisters abolished forced public school enrollment and declared that parents had the right to direct the education of their children. Education choice opponents’ court challenges to education choice programs, and supporters’ challenges to Blaine amendments will no doubt continue as the nation’s transition to a new era of public education begins.

Michigan businessman and former boxing promoter Franklin Fudail is taking advantage of the flexibility charter schools offer by launching one that will focus on STEM learning while stressing discipline, respect and service in a military-style environment.

A new charter school seeks to capitalize on its proximity to the shores of Lake Michigan as it works to raise critically low math and reading rates.

Muskegon Maritime Academy will open Sept. 6 in a former district elementary school to students in kindergarten through fifth grade, offering water education in a military-style environment. More than 100 students have enrolled at the school which will focus on STEM learning while teaching discipline, respect, and service, according to the schools’ website.

Entrepreneur Franklin Fudail, who founded the academy after establishing a youth boxing club that provided free tutoring services, said he sees the school’s format as an effective way to boost to sagging math and literacy rates.

Figures from the Michigan Department of Education show only 3.5% of Muskegon third graders tested as proficient in math last year on the M-STEP, Michigan’s standardized test; only 4.6% tested as proficient in reading.

Among fourth graders, 3% were proficient in math, while 10.4% showed proficiency in reading. In fifth grade, 4.3% were proficient in math, while 11.2% scored as proficient in reading.

Analysts attributed the declines to the pandemic and the fact that not all students took the tests in 2021, warning not to read too much into the scores. But statewide results from before the pandemic also showed declines, especially among districts with more low-income households.

Fudail said scores were embarrassingly low years before the pandemic.

“For years, test scores have been — pardon my language —in the toilet,” Fudail said, adding that some years, several schools reported zero percent of student as proficient in math.

That’s why he started the after-school youth boxing program, a six-week boot camp that he ran for 11 years to help boys catch up on learning losses in math and language arts and to instill a sense of discipline.

“The boxing was just a draw,” he admitted.

Each student was immediately required to write a letter to his or her teachers to inform them they were in the program, apologize for any misbehavior, and ask for a fresh start at school.

Fudail later added a similar program in the summer for girls. The two-hour-per-day program, which ran five days a week, made a positive difference. Teachers told him of students who had once hated school making turnarounds.

In some cases, Fudail said, his efforts to help students kept many from being placed in special education programs, which happens disproportionately to minority students.

“Most of them just need some extra help,” he said, adding that many were able to do well in math once the teachers he hired figured out where the students had fallen behind and helped them understand the concept that had become a stumbling block.

After closing the after-school program in 2015 to focus on his other businesses, Fudail began the process of opening a full-fledged school in 2019. He said a conversation he overheard one Friday at the boxing club helped spark the idea.

“One young man told another young man, ‘I wish we could go to school here,’” Fudail recalled. “They didn’t know I heard that.”

He said his new project will allow him to help more kids in Muskegon, a coastal community with a population of 38,302 and a poverty rate of about 25%. His plan to focus on STEM – science, technology, engineering, and math – is designed to prepare students for high-wage jobs.

Nolan and Dakota Washington

That came as welcome news to Shanavia Washington, whose kids are not struggling but seeking to get ahead. She recently enrolled her son, Nolan, 7, and his sister, Dakota, 5.

“I hope they become more confident and really pick up on robotics,” she said.

Washington also like the fact that the school will offer Saturday tutoring to those who need extra help.

The water education and leadership training parts of the program will be provided through a partnership with the United States Naval Sea Cadets Corps and will be incorporated into the curriculum. Students also will learn about maritime research.

Fudail says he chose to base his program on the Navy’s youth group because students as young as 10 can participate; other military youth programs such as the Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps don’t start until high school.

Fudail also is partnering with My Dress Rehearsal, a Grand Rapids-based etiquette company, to teach students about proper table manners and communication. Additionally, all students will receive weekly martial arts and self-defense training to develop self-confidence, discipline, and teamwork.

The charter school is authorized by Saginaw Valley State University. The university, founded in 1963, offers 100 academic programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels with approximately 9,000 students from 42 different nations and more than 1,300 faculty and staff members working across five colleges.

Saginaw Valley State has offered $6,000 per year scholarships to students who complete grades 3 through 5 at Muskegon Maritime Academy and who meet the college’s admissions and scholarship criteria.

Fudail said expects to keep his school small, limiting it to no more than 150 students. He said he watched a couple of charter schools open in the late 1990s, only to fold because they got too large and lost their focus.

“They were just going for the numbers,” Fudail said. “This school is not a job for me. I have a job. I want to make a difference in my community.”

Northern Michigan Christian Academy, one of 878 private schools in the state serving more than 143,000 students, aims to develop God-honoring discipline through academics, attitudes, and actions, encouraging students to master all subject matter necessary for completion of their high school diplomas.

Backers of the Let MI Kids Learn petition drive, launched to establish a program in Michigan that would allow donors to contribute to a private scholarship fund and receive tax credits, say there are more than 520,000 signatures on the document filed Wednesday with the Bureau of Elections.

The group, backed by former U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, plans to put the initiative before the Republican-led Legislature for approval this year. If certified, the Michigan House and Senate could enact the new scholarship proposal despite Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s veto of the program last fall.

“This is the day that parents and families have been working for, and I am excited to know that change is on its way,” said Michigan Sen. Lana Theis. “Every child deserves a chance to catch up on the learning they lost, and the public school system isn’t the only place where that can happen.”

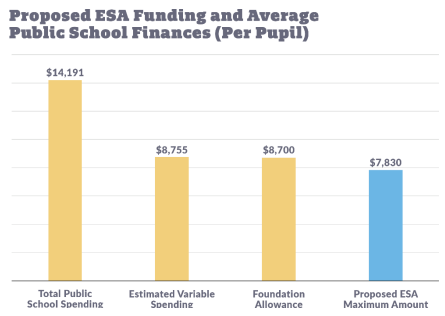

Michigan’s scholarships would go to families making no more than twice the level needed to qualify for free and reduced-price meals. For this year, that's $102,676 for a family of four. The program would cap private tuition at 90% of Michigan’s minimum per-pupil funding amount, which is $8,700 this year.

If the initiative becomes law in Michigan, the state would have one of the largest tax credit scholarship programs among states with similar options. Only Florida would have a higher cap at $874 million.

A press release about the petition issued Wednesday by Let MI Kids features a Michigan parent who says the proposal offers hope and puts education choices in reach for every family.

“These educational scholarships, funded with private contributions, have been extremely successful and popular in other states, and we deserve to have these choices for Michigan children, too,” said Tanya Armitage-Edgeworth. “There are families who could never dream of being able to afford to choose a better school for their kids.”

The measure could face a legal challenge in Michigan, where the state constitution bars the use of public dollars to “directly or indirectly aid or maintain” private education. Proponents of the Michigan initiative have argued the petition language is “well-crafted” and would survive any constitutional challenge.

“It is not the government sending money to a religious or faith-based school or any other school,” DeVos told reporters at a recent promotional event. “The reality is these funds are going to families to decide where to best send their children and find the right fit for them.”

Petition campaign spokesman Fred Wszolek said his group is looking forward to the initiative being swiftly canvassed by the Bureau of Elections and promptly certified by the Board of State Canvassers.

“There is plenty of time for the Legislature to enact these proposals into law before the end of the year,” Wszolek said. “Special interest groups fought hard to keep this day from ever happening. But you can’t stop an idea whose time has come.”

The advocacy group plans to file a separate initiative petition for an income tax credit for scholarship fund contributions.

Grand Rapids Christian Schools provides high quality, faith-based education to Michigan students in preschool through 12th grade on five campuses to educate nearly 2,300 students annually. The school offers programs in Spanish immersion, fine arts, and instructional technology.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Ben DeGrow, director of education policy at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy based in Michigan, appeared Monday on the center’s website.

There is an understandable challenge in writing about Michigan’s attempt to expand parental choice in education. Until recently, journalists who cover state issues and debates have had little reason to investigate the larger movement, even as Michigan remains surrounded by states that have adopted private education choice programs.

Providing accurate coverage of Student Opportunity Scholarship accounts is also complicated by the policy’s numerous moving parts. The proposal is designed to give parents greater flexibility and meet many students’ educational needs. It is also carefully crafted to clear the formidable legal barrier the state maintains through its “Blaine Amendment.” Grasping the full mechanics of the proposal takes significant effort.

As time goes on, though, there’s less justification for labeling the proposal as a “voucher-like” program, as a recent Bridge Michigan article describes it. (Chalkbeat Detroit earlier had to correct misrepresentations in its description of the proposal.)

The term “voucher” elicits a negative reaction from a sizable segment of voters otherwise favorable to choice. Yet Michigan’s proposal differs from school vouchers in two key respects: Funds come from incentivized private donors rather than a government treasury and unlike vouchers, they can be used for a wide variety of educational expenses, rather than just private school tuition.

To continue reading, click here.

The Let MI Kids Learn plan would create K-12 education savings accounts that families could use for tuition at private schools such as Oakland Christian School as well as a wide range of education expenses to customize their children’s education.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Wednesday on detroitnews.com. To read more about the Let MI Kids Learn initiative, click here.

A ballot initiative creating a tax-incentivized scholarship program that could be used for private school tuition plans to continue collecting signatures in the coming weeks, missing a Wednesday deadline that would have guaranteed review of signatures ahead of the November election.

The Let MI Kids Learn ballot committee said it would continue collecting signatures over the next few weeks to ensure the total collected could stand up to expected challenges, but the group maintained it had met the minimum of 340,047 signatures.

"But we also know the well-funded special interest groups and school unions that oppose these scholarships will conduct a no-holds-barred effort to stop them from becoming law," said Fred Wszolek, a spokesman for the group. "It’s sad that some will put their self-interest over the needs of children, but we won’t let them win."

Opposition group For MI Kids, For Our Schools argued Wednesday that a lack of support for the proposal was driving organizers to circumvent the November ballot in favor of later passage by the GOP-led Legislature.

"They’ll continue to try to force their latest anti-public education voucher scheme on the people of Michigan, and we will continue to fight it, alongside the majority of Michiganders," said Lonnie Scott, executive director of liberal advocacy group Progress Michigan and a spokesman for For MI Kids, For Our Schools.

The delayed submission of signatures puts the ballot initiative at somewhat of a disadvantage compared with other ballot initiatives planning to submit their signatures to the Bureau of Election by the Wednesday deadline.

Submission of signatures by Wednesday requires the Bureau of Elections to review the signatures ahead of the November election, so that the measure may be placed on the November ballot.

To continue reading, click here.

Established in 1954, South Christian High School in Grand Rapids, Michigan, is a private school dedicated to educating young people from a Reformed Christian perspective, incorporating Christian values and principles into rigorous academic study and extracurricular challenges.

Michigan’s tax-credit-funded education savings account program could save state and local governments as much as $386 million a year, according to new research from the Mackinac Center for Public Policy.

The paper, “Michigan Student Opportunity Scholarships, Overview and Fiscal Analysis,” by Ben DeGrow and Marty Lueken, provides several estimates relating to the program’s cost and savings. On the lower end, the researchers estimate the program costing the state as much as $106 million.

The program also has the potential to save between $90 million and $386 million a year. Estimates depend on the average size of the awarded scholarship and the percentage of students switching from public schools to private ones.

Michigan’s ESA initiative, currently stuck in limbo following a veto of the legislation by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in November, would provide students with scholarships averaging $7,830. Eligible students would come from low- and middle-income households averaging less than $98,000 a year for a family of four. Students with disabilities or students in foster care also qualify.

Individual and corporate donors receive a 100 percent tax credit for their contributions, but total tax credits are limited to $500 million each year. The law allows scholarship-granting organizations to keep 10 percent of the funds raised to cover administrative costs.

Parents would be able to use the scholarship accounts to pay for private school tuition, tutoring, dual enrollment classes, AP courses, afterschool programs, special-needs therapies, career counseling, and transportation to and from school.

Opponents argued the voucher program will siphon upward of $50 million a year away from public schools, a relatively small fraction of the state’s $17 billion public school budget.

After Whitmer’s veto, proponents, including, Let MI Kids Learn, assembled a petition that could potentially bypass the veto. The petition will need 340,000 signatures.

Michigan ranks 10th in the nation on the Education Freedom Index, thanks to its home education and charter school systems. DeGrow and Lueken argue that ranking is held back by the state’s constitutional ban on school vouchers.

Michigan is the only state to expressly forbid school vouchers thanks to a voter-approved constitutional amendment dating back more than 50 years. Michigan’s constitutional ban on direct or indirect subsidies to private schools is one of the strongest in the nation, though a portion of the amendment was struck down in Traverse City School District v. Attorney General (1971).

Recent U.S. Supreme Court cases, such as Espinoza v. Montana, have also called into question outright bans on school choice scholarships.

The National School Choice advocacy team reports that Michigan is one of the most constitutionally restrictive states for school choice, with no state-run scholarship opportunities that make private school more accessible to Michigan families.

Editor’s note: This article from Ben DeGrow, director of education policy at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, appeared Thursday on the center’s website.

The evidence is in: Demand for private school enrollment is growing in Michigan, reversing a years-long trend. For those concerned that this trend might worsen educational gaps between rich and poor, voters have a solution right now.

A recent Bridge Michigan piece highlights the resurgence of students attending private education options. In the two years since reaction to the pandemic disrupted normal routines, private religious schools have welcomed an extra 3% to 5% of students. This represents less than half of the losses Michigan private schools experienced in the previous decade.

A driving factor for the rebound is that these schools consistently kept classrooms open, in clear contrast with many school districts’ remote instruction programs.

Over the last two years, public school enrollments have dropped at about the same rate as their private school counterparts have risen. Districts that denied students in-person options for most of 2020-21 experienced some of the biggest declines.

University of Michigan education professor Kevin Stange, who has been researching the state’s school enrollment trends, observes that most families who switched from public to private education have not returned.

The Bridge article cited Stange’s concerns about expanding achievement gaps because more affluent families can find a way to pay tuition. Private school is “not an option for lower-income families,” he said.

To continue reading, click here.

Two Michigan education choice advocacy groups, Let MI Kids Learn and Great Lakes Education Project political action committee, are using a provision in the state constitution they say will take power away from unions and the governor and put it in the hands of families.

Two vetoed bills that would empower education-minded families for the first time in Michigan’s history are getting another chance to become law, thanks to a provision in the state constitution.

Michigan’s Republican-controlled legislature approved the bills last year that would have established an education savings account program to offer choice to families who meet income eligibility guidelines or who have children in foster care or with special needs.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer vetoed both bills, which were opposed by the state’s teachers’ union.

Education choice advocacy groups, however, have refused to give up. Let MI Kids Learn and Great Lakes Education Project political action committee are using a provision in Michigan’s constitution that allows petitions that garner 340,000 signatures to be put up for a legislative vote.

Measures that are approved by voters bypass the governor and become law.

“The Let MI Kids Learn proposal would put parents back in charge. It’d create new Student Opportunity Scholarships so kids can get the extra tutoring, transportation, Internet access and other resources they need to succeed inside and outside the classroom,” wrote Beth DeShone, executive director for the Great Lakes Education Project.

As of last week, the groups have gathered more than 70,000 signatures since the campaign kicked off in February. The deadline for submitting signatures to the state is June 1.

The first Let MI Kids Learn petition would change Michigan tax law to allow donors to give money to “scholarship-granting organizations,” or newly created nonprofits that would provide parents and families funding for students who match certain criteria.

The funding could be used for tuition or fees to attend a private school, tutoring, or extracurricular activities and other educational resources. Public school students who are eligible based on income could get up to $500, while students with disabilities could receive up to $1,100.

The second petition allows donors to claim tax breaks on their contributions to the scholarship program. Residents or corporations making donations would be eligible for income tax credits equal to their donations. Let MI Kids Learn set a $500 million maximum in tax credits that could be claimed.

Despite being the home state of former U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who has strongly supported choice for decades, Michigan has never had a robust choice program. Most of the choice that does exist is in the form of district magnets, specialized programs, and inter-district programs.

Charter schools have fared better, especially in the state’s urban areas, said Ben DeGrow, director of education for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a Michigan free market think tank.

(For a deep dive into the history of education choice in Michigan, click here.)

For Michigan, the state constitution has been a double-edged sword for education choice. The same document that allows for a possible gubernatorial workaround also includes language that has been used to oppose choice.

A 1970 Blaine amendment in Michigan’s constitution prohibits any “payment, credit, tax benefit exemption or deduction, tuition voucher, subsidy grant or loan of public money” from being provided “directly or indirectly to support the attendance of any student at any nonpublic school.”

An attempt to change the constitution to let the state grant scholarships to Michigan students in struggling district schools failed in 2000 with only 30% in favor. The latest choice initiative is different in that it relies not on state funds but on tax-credit donations from private donors.

In 2017, choice supporters saw a possible opening to challenge the Blaine amendment when Congress approved the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Before the new law, families could spend their 529 savings plans – tax-advantaged investment vehicles designed to encourage savings for future higher education expenses – only on college expenses.

Now, they can use the savings plan to pay up to $10,000 in tuition expenses at K-12 public, private or parochial schools. Supporters say the change puts Michigan’s constitution at odds with federal law.

In response to the new federal law, the Mackinac Center Legal Foundation sued the state in September on behalf of five families who say they want to provide the best education possible for their children by using the federally administered accounts to send their children to private schools. Hile v. Michigan is pending in the U.S. District Court of West Michigan.

The lawsuit argues, among other things, that the original 1970 amendment was motivated by religious bigotry. According to the complaint, the amendment was adopted "in response to a modest proposal to appropriate $150 per student in funding for private schools, which were then more than 90% religious, spurred on by an antireligious ballot sponsor (the 'Council Against Parochiaid') and by anti-religious, especially anti-Catholic, advertisements, campaign literature, and letters to the editor."

DeGrow said recent court victories related to education choice such as Espinoza v. Montana, along with a more conservative U.S. Supreme Court, gave education choice supporters hope for a similar victory in Michigan.

If that happens, choice opponents would have more difficulty challenging laws that establish education choice programs.

Tuition at the approximately 900 private schools in Michigan, such as North Bridge Christian Academy in Howell, averages $7,235 per year. Supporters of school choice in Michigan are battling on two fronts to open the door to school vouchers, taking their fight to the courts and the state Legislature in a renewed push for additional education choice.

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on nationalreview.com.

Jessica Bagos is the kind of mom who may be on the verge of transforming K–12 education.

“I grew up in public schools, and I’ve always been a proponent of the public-school system,” she says.

Then came the COVID9 lockdowns. The public schools closed in Royal Oak, Mich., the Detroit suburb where she lives. When her twin sons were ready to enter kindergarten at the beginning of the last school year, the schools stayed closed. Her boys could connect with a teacher by video conference, but they couldn’t attend class in person.

“You can’t put five-year-olds in front of monitors for hours and hours every day,” she says.

Yet for months, her daily challenge was to stop them from wrestling with each other and instead keep them fixed to screens while she tried to hold down a full-time job from her home.

“I used to cry in the mornings,” says Bagos. “Then I got mad.”

Last September, she and her husband sued Michigan’s government in federal court, joining several other parents who had suffered from their own frustrations. They seek to overturn an amendment to their state’s constitution that forbids them to pay for private education with money from a state-sponsored savings plan. For more than half a century, the amendment has blocked Michiganders from enjoying any form of school choice (apart from the kind paid for with personal funds) outside the public-school system.

Meanwhile, other parent activists in Michigan have launched a petition drive that could create a $500 million program of educational savings accounts, allowing families to pay for more kinds of education expenses for their kids, such as transportation costs, speech therapy, and tuition at Catholic schools and cosmetology colleges.

Ben DeGrow, of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, the state’s free-market think tank, says that these combined efforts may lead to a watershed moment: “Everything about education in Michigan could change this year.”

To continue reading, click here.

Detroit Country Day School, with campuses in Bloomfield Hills and Beverley Hills, Michigan, is a private, independent, non-denominational school serving children from preschool through Grade 12 with a focus on a well-rounded, college preparatory liberal arts education.

Both the Michigan House and Senate are advancing bills, introduced last week, that would provide tax credits to residents who contribute to a scholarship program for students to use at schools of their choice.

Under the legislation, individuals could contribute money toward scholarship-granting organizations under the Student Opportunity Scholarship program. The program would be capped at $500 million in contributions each year.

Republican Sen. Lana Theis, who sponsored the bills alongside Republican Sen. Tom Barrett, said that after a “year unlike any other,” it’s time for the state to rethink education.

"There is no reason our kids can’t be among the most successful in the country, but doing things in the same way over and over again will not lead to success," Theis said.

Students eligible to receive a scholarship would include those in households with an income under 200% of the financial eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch, have some sort of disability, are in the foster care system or have someone else in their household receiving funds through the Student Opportunity Scholarship program.

Money could be used for tuition or fees for public or private school education, online learning programs, tutoring, extracurricular programs, textbooks and instructional materials, computer hardware, uniforms, standardized test fees, summer school, after-school programs or childcare, dual enrollment, transportation, sports fees and career technical programs.

Funding for public school students would be capped at $500, or for a public school with a disability, at $1,100. For nonpublic school students, funding would be capped at 90% of the minimum foundation allowance spent on public school students, minus three-eights of the percentage that the household income exceeds free or reduced-price lunch eligibility criteria.

Nonprofits wising to participate in the program will be able to apply to the Michigan Department of Treasury to become a scholarship-granting organization.

Since the bill packages are separate, one or the other must be approved by the opposite chamber before heading to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer for her signature.