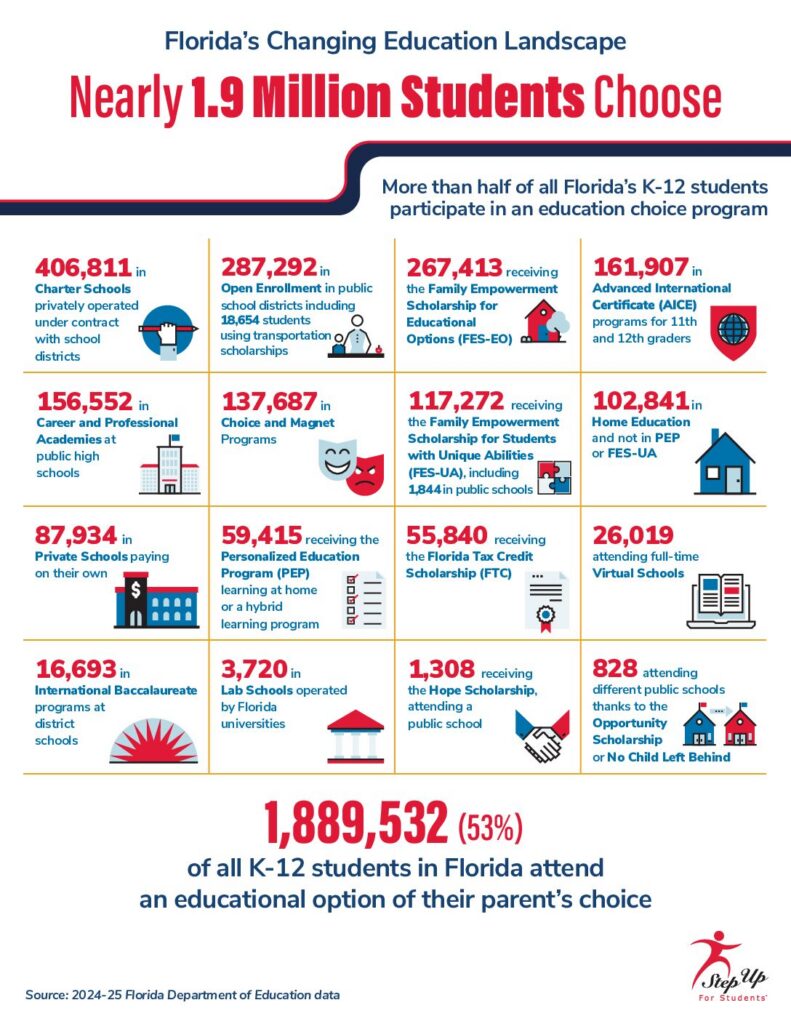

Florida’s K–12 education landscape continues to shift toward choice. During the 2024–25 school year, 53% of all K–12 students — 1,889,532 children — attended a public, private, or home education option of their parents’ or guardians’ choice. Just one year after crossing the 50% threshold for the first time, Florida’s school choice participation grew by nearly 100,000 additional students.

“Each year, Florida families have made it clear that they want more options for their children’s education,” said Gretchen Schoenhaar, CEO of Step Up For Students, the Florida non-profit that administers the state’s education choice scholarship programs.

“Increasingly, parents and guardians are willing to mix and match private and public resources to choose the ones that work best for their family.”

Since the 2008–09 school year, Step Up For Students, in collaboration with the Florida Department of Education, has tracked enrollment across a variety of choice programs. The 2023–24 school year represented a historic milestone: the first time more than half of all K–12 students in the state attended a school of choice. The 2024–25 school year continued that upward trend.

The Changing Landscapes report draws from Florida Department of Education data and removes, where possible, duplicate counts to provide a clearer picture of school choice participation. For example, it adjusts for home education students supported by the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA) and eliminates double-counted students in career and professional programs. It also excludes prekindergarten students in FES-UA and programs such as Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten (VPK), as the report focuses solely on K–12 education.

While many families still choose their neighborhood public schools, Florida’s education system now offers a broad range of options to meet diverse student needs. As in past years, public school choice remains dominant, occupying four of the top five spots in overall enrollment. Charter schools are the most popular single option, followed by district open enrollment programs, the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options (FES-EO), career and professional academies, and Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) programs for upperclassmen.

The largest increases in enrollment occurred in the FES-EO program, which has merged with the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, and the Personalized Education Program (PEP), a scholarship that helps fund education at home.

Among public school options, AICE enrollment grew nearly 17%, career and professional academies grew 6.2%, and open enrollment grew 4.6%. While overall district enrollment appeared to decline slightly, these public school choice options still grew more than charter schools (independent public schools), which grew just 2.3%. This may suggest that school districts could benefit from expanding their own menu of diverse school options to better retain families.

Choice remains strong within Florida’s public school system. More than 1.2 million of the state’s 2.9 million public school students attended a school of choice, while another 688,000 students outside the public system enrolled in private schools or home education programs.

A newer option to keep an eye on is district schools offering classes and services to students on an education choice scholarship, paid for with their scholarship funds. Currently 37 of Florida’s 67 districts have been approved as providers with Step Up For Students, and another 11 are in the process of being approved. These arrangements further blur the line between public and private and emphasize that the focus remains on the individual needs of students.

With so many options available, Florida’s education system has entered a new phase. Choice is no longer an alternative; it is the norm. Families routinely evaluate multiple pathways, and whether they select a different option or remain in their assigned public school, they are making an active choice. The result is an education landscape in which public, private, and home education options coexist and evolve together, reflecting the reality that students and families have different needs, and that those differences matter.

A Tampa Bay area morning TV show kicked off National School Choice Week by highlighting a family who benefits from a state K-12 scholarship.

Arielle Frett appeared on Fox 13’s “Good Day Tampa Bay” program on Monday with her son, AnyJah, a ninth grader at The Way Christian Academy in Tampa. She said she moved to Florida from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, in 2017 to find better educational opportunities for AnyJah, who has severe autism.

“No teachers were able to work with him on his level,” Frett told Fox 13 reporter Heather Healy. “Most of his learning in English and math are on fifth and sixth grade levels now.”

A U.S. military veteran and single mother of two, Frett said she would not have been able to afford a private school for her son without the scholarship.

She said AnyJah, who receives the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities, is “loved, protected, and thriving” at his school, where class sizes of 10 to 12 students allow for more individual attention. He can also receive his therapies during school.

The segment also featured information about Florida’s robust education choice options. Those include traditional public schools, district magnet schools, charter schools, private schools, microschools, homeschools, virtual schools, and customized education programs that allow parents to mix and match.

“We’ve gone from education and funding through the system to now empowering families by putting the money in their hands and allowing them to make the most appropriate educational decisions for families,” said Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, which administers most of the state’s education choice scholarships.

Jacobs has spent the past year working with school districts to provide individual courses to scholarship families whose students do not attend public or private school full time, paid for with scholarship funds. About 70% of Florida school districts are participating.

The scholarship application season for the 2026-27 school year begins Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to learn more and apply.

Gevrey Lajoie visited a School Choice Safari event to learn about options for her son, Elijah. The event was sponsored by GuidEd, one of the many organizations springing up in states that have granted parents the flexibility to choose the best educational fit for their children.

TAMPA, Fla. — Parents, many pushing babies in strollers with school-age children in tow, made their way through the covered pavilion as they surveyed the brightly decorated tables representing 28 local schools.

Their goal: To gather as much information as possible as they try to figure out the best educational fit for their children, either for the 2025-26 school year or beyond.

“We’re all over the place with which school,” said Gevrey Lajoie of South Tampa. Her son, Elijah, is only 3, but she said it’s not too early to begin looking at options. A mom friend told her about the School Choice Safari at ZooTampa at Lowry Park. It would give her a chance to check out many schools all in one place and learn about state scholarship programs.

Lajoie isn’t alone. For this generation of Florida families, gone are the days of simply attending whatever school they’re assigned based on where they live. Families actively shop for schools; schools actively court them, and districts perpetually create new programs.

And while the benefits are clear, some families end up feeling adrift in a sea of choices.

New organizations are springing up to help families find their way. "A variety of options are out there, and the number is growing, but families don’t know how to navigate them. There was no place for them to go to get help,” said Kelly Garcia, a former teacher who serves on Florida’s State Board of Education.

New organizations are springing up to help families find their way. "A variety of options are out there, and the number is growing, but families don’t know how to navigate them. There was no place for them to go to get help,” said Kelly Garcia, a former teacher who serves on Florida’s State Board of Education.

In 2023, the Tampa Bay area resident and her brother-in-law, Garrett Garcia, co-founded GuidEd, a nonprofit organization that provides free, impartial guidance to help families learn about available options so they can find the best fit for their children.

The organization hosts a bilingual call center where families can get information about all options in Hillsborough County, from district and magnet schools to charter schools, private schools, religious schools, online schools and even homeschooling. GuidEd also helps families sift through the various state K-12 scholarship options. The group also hosts live events, such as the School Choice Safari, to connect families and schools.

Organizations are cropping up all over the country, especially in areas with lots of choices. Their specific missions and business models vary, but they are united by a common theme: They help families navigate an evolving education system where they have the power to choose the best education for their children

Jenny Clark, a homeschool mom and education choice advocate, saw the need for a personal touch in 2019 when she launched Love Your School in Arizona.

“One of the most important aspects of our work is knowing how to listen, evaluate, and support parents who want to talk to another human about their child's education situation,” said Clark, who had seen parents struggle with the application process surrounding the state’s new education savings accounts program. The program has since expanded to West Virginia and Alabama.

Clark’s nonprofit provides personalized support through its Parent Concierge Service, which offers parents the opportunity for phone consultations with navigators. Love Your School also provides free online autism and dyslexia guides and details about the legal rights of students with disabilities, and it hosts an online community where parents can get support.

“Our services are unique because we pride ourselves in being experts in special education evaluations and processes, which are required for higher ESA funding, public school rights and open enrollment, experts in the ESA program law and approved expenses, and personalized school search and homeschool support,” Clark said.

Kelly Garcia, GuidEd’s regional director, has hosted several in-person events that feature free snacks, face painting, magicians, and prize giveaways in addition to booths staffed by schools and other education providers. During the recent event, parents could visit a booth to learn more about the state’s K-12 education choice scholarship programs.

Garcia, whose organization prioritizes neutral advice about all choices, including public schools, advises parents to start by assessing their child’s needs and then identifying learning options that would best serve them. GuidEd’s philosophy is to trust parents to determine the best environment for their kids.

At the School Choice Safari, families got to check out private schools, magnet schools and charter schools.

“There’s a school out there for everyone,” she said.

Students at New Springs Schools, a STEM charter school that serves students ages 5-14, show off some recent class projects at the School Choice Safari in Tampa.

During the zoo event, Garcia personally escorted parents with specific questions to the tables where they could get answers.

One of them, Hugo Navarro, recently moved to Tampa from Southern California to start a new job for a national investment firm. His wife, who had remained with their three kids in California, had already started researching schools online, but Navarro wanted to get an in-person look at providers and learn more about state education choice scholarships before their 7-year-old son starts school in August.

On his wish list: academic rigor, a focus on the basics, and a diverse student body.

“Academic ratings, that’s our number one thing,” he said.

A Catholic school that offers academic excellence was also a contender, though a secular school wouldn’t be a dealbreaker if it had a reputation for strong academics.

Garcia and Clark both said that as new generations of parents grow more comfortable selecting education options, they see the navigators’ role becoming more relevant, not less.

“Parents can use online tools like google to search for schools, but the depth of what parents actually want, and our highly trained knowledge of a variety of educational issues means that as choice programs grow, the need for our parent concierge services will continue to grow as well,” Clark said. “There are exciting times ahead for families, and those who support them.”

As the number of schools and a la carte learning options grows, Garcia said, families will need information to better customize learning for their children.

“This is a daunting task, even for the most seasoned parents,” she said. “At GuidEd, we see a growing need for unbiased education advisers to ensure a healthy and sophisticated market.”

Garcia compared the search for educational services to buying a home.

“A family is not likely to make a high-stakes decision, like buying a home, by relying on a simple Zillow search,” she said. “Instead, they use the Zillow search to help them understand their options and then rely on a Realtor to help guide them through the home- buying process, relying on their trusted, yet unbiased expertise. We see ourselves as the "Realtor" in the school choice or education freedom landscape.”

Public education in the United States is transitioning from its second to third paradigm.

Paradigm shifts in public education occur when larger societal changes force public education to change to meet these new conditions. Current technological advances and the accompanying social changes are pushing public education into a new paradigm and a third era.

To best meet society’s current and future needs, this third paradigm aspires to provide every child with an effective and efficient customized education through an effective and efficient public education market.

A paradigm: The lens through which communities do their work

In his 1962 book, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn described a paradigm as the lens through which a community’s members perceive, understand, implement, and evaluate their work. A paradigm includes a set of assumptions and associated methodologies that guide how communities construct meaning and determine what is true and false and right and wrong.

A paradigm shift occurs when inconsistencies, which Kuhn called anomalies, begin to occur, and some community members begin to question their paradigm’s veracity and effectiveness. As these anomalies accumulate, community members begin proposing new ways of understanding and implementing their work and a prolonged contest emerges between the existing paradigm and proposed new paradigms. If a majority of the community ultimately decides a new paradigm enables them to resolve the anomalies and better understand their discipline, this new paradigm is adopted. In scientific communities, Kuhn calls these paradigm shifts scientific revolutions.

Paradigm shifts are disruptive and revolutionary because they require community members to reinterpret all their previous work and adopt new ways of conducting and evaluating their future work. Senior community members are particularly resistant to changing paradigms because their status comes from applying the existing paradigm over many years. Consequently, paradigm changes are rare and require several decades to complete.

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GTR) was a new physics paradigm that challenged Newtonian mechanics and Newton’s law of universal gravitation (i.e., the dominant physics paradigm at the time). It took over 40 years before GTR gained wide acceptance among physicists. Einstein never won a Nobel Prize for GTR because the Swedish physicists on the Nobel committee refused to accept his new paradigm.

Although Kuhn’s work focused on the role of paradigms in scientific communities, his description of how paradigms function and change is relevant for all communities, including public education. The struggle in U.S. colonial times to transition from a monarchy to a democracy was a paradigm shift. It was a revolutionary change in how government works, was fiercely resisted by those in power, and took decades to complete.

Public education’s first paradigm

Public education’s first paradigm began before the United States was a country, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the “Old Deluder Satan Act” to ensure the colony’s young people learned scripture. As the name of that early legislation implies, this first era prioritized basic literacy and religious instruction. Most children were homeschooled, and formal instruction tended to be ad hoc, improvised, and organized around the agricultural calendar.

Religious organizations provided most of the structured instruction outside the home in the 1700s and early 1800s. Children and adults attended Sunday schools, and communities organized what today we would call homeschool co-ops, which allowed rural children to receive instruction when their chores permitted.

The federal government supported public education through the U.S. Postal Service by subsidizing the distribution of magazines, pamphlets, books, almanacs, and newspapers, and establishing post offices in rural communities. By 1822, the U.S. had more newspaper readers than any other country.

Public education’s first paradigm started failing in the early 1800s as innovations in transportation and communications began connecting the country and promoting more industrialization and urbanization. About 90% of Americans lived on farms in 1800, 65% in 1850, and 38% in 1900.

This transition from rural to urban created childcare needs. Increased industrialization necessitated a more highly skilled workforce. And concerns about social cohesion grew as the growing country welcomed immigrants from Ireland and later from Southern and Eastern Europe. These were demands the informal, decentralized, and family-driven first public education paradigm was ill-equipped to meet.

Public education’s second paradigm

In 1852, Massachusetts passed the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law. This accelerated public education’s shift from its first to second paradigm.

The massive influx of European immigrants beginning in the 1830s was a primary reason Massachusetts decided to make school attendance mandatory. The U.S. experienced a 600% increase in immigration from 1840 to 1860 compared to the prior 20 years. Most of these immigrants were illiterate, low-income, and Catholic. Massachusetts’ mandatory school attendance law was intended to help turn these new immigrants into “good” Americans, meaning they needed to be literate, financially self-sufficient, and well-versed in Protestant theology.

Protestant hostility toward Catholic education in the U.S. continued deep into the following century and included the infamous Blaine Amendments that many states adopted in the late 1800s to forbid public funding of Catholic schools, and the 1922 constitutional amendment in Oregon that required all students to attend Protestant-controlled government schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Oregon amendment unconstitutional in its 1925 decision Pierce v. Society of Sisters, ensuring every American family had the right to choose public or private schools for their children. This ruling would later help make public education’s transition to its third paradigm possible.

By 1900, 31 states had passed mandatory school attendance laws. While these laws were not initially well enforced, they did significantly increase school attendance, which created management challenges.

As David Tyack chronicles in “The One Best System,” a history of how this first paradigm shift unfolded in America's cities, a new class of professional administrators, known as schoolmen, set out to modernize public education practice and infrastructure. One-room schoolhouses serving students were no longer adequate, so public education began adopting the mass production processes that enabled industrial manufacturers to create large numbers of products at lower costs. The most famous example was the assembly line that Henry Ford created to mass produce affordable Model Ts.

This new industrial model of public education replaced multi-age grouped students with age-specific grade levels that functioned like assembly line workstations. Just as Ford’s assembly line workers were taught the skills necessary for their workstations, public school teachers were trained to teach the skills associated with their assigned grade level, and children were moved annually from one grade level to the next en masse.

Mississippi became the last state to pass a mandatory school attendance law in 1918. By then the bulk of multi-aged one-room schools were being replaced with larger schools that reflected the best practices of 19th century industrial management. This was the paradigm through which government, educators, families, and the public were now seeing and understanding public education. This change marked U.S. public education’s second paradigm.

Ford famously told customers they could have any color of Model T they wanted provided it was black. Public education adopted this one-size-fits-all approach to increase efficiency. Car consumers began demanding more diverse options over the next several decades, and so did public education consumers. The auto industry diversified its offerings much quicker than public education because it faced competitive pressures the public education monopoly did not. But in 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required all school districts to begin adapting instruction to serve special needs students. This was the first instance of government requiring public education to provide a large group of students with customized instruction.

Public education’s third paradigm

This expansion of instructional diversity accelerated in the late 1970s and early 80s as school districts started creating magnet schools to encourage voluntary school desegregation. The school district in Alum Rock, California even experimented with a short-lived voucher program that fostered an ecosystem of small, specialized learning environments that today would be called microschools.

Most of the beneficiaries of early magnet schools were white middle-class and upper middle-class families who were attracted by the additional resources and high-quality specialized instruction. But magnet schools created for desegregation could serve only a limited number of students. In response to political pressure from influential constituents, school districts began creating magnet schools unrelated to desegregation, which expanded and normalized specialization and parental choice within school districts and accelerated the transition to public education’s third era.

Florida added significant momentum to this transition with the passage of its 1996 charter school law, the founding of the Florida Virtual School in 1997, and the 2001 creation of the nation’s largest tax credit scholarship program.

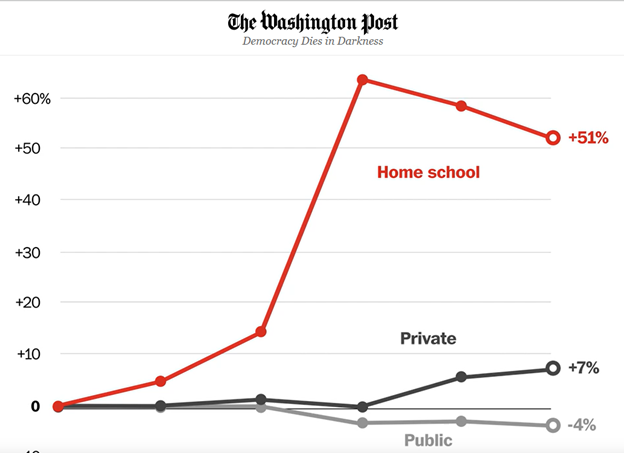

Two decades later, the COVID-19 pandemic further hastened public education’s current paradigm shift. Magnet schools, virtual schools, charter schools, homeschooling, open enrollment, homeschool co-ops, and tax credit scholarship programs were already expanding nationally when COVID arrived in March 2020. The pandemic turbo charged the growth of these options and newer options such as microschools, hybrid schools, and education savings accounts (ESAs).

Just as 19th century innovations in communications, transportation and manufacturing led to public education’s first paradigm shift, the rise of digital networks, mobile computing, and artificial intelligence are transforming all aspects of our lives, including where and how we work, communicate, consume media, and educate our children. These technical and societal changes are driving a decline of trust in institutions that no longer enjoy a monopoly on public information. They are also driving increased demand for flexibility to determine when, where, and with whom teaching and learning happen. Public education has begun to adopt a paradigm more aligned to 21st century demands, which include parents gaining more power to decide how their children learn.

Government’s changing role

Government’s role in public education will be impacted by a new public education paradigm that reflects these ongoing technical and cultural changes. Under the second paradigm, government had a near-monopoly in the public education market. This quasi-monopoly undermined public education’s effectiveness and efficiency because it failed to take full advantage of the knowledge, skills and creativity of students, families and educators.

In public education’s third era, government will regulate health and safety and help facilitate support services for families and educators but will no longer be the dominant provider of publicly-funded instruction. This regulatory and support function is like the role government currently plays in the food, housing, health care, and transportation markets. Most of the responsibility for how children are educated will shift from government to families and the instructional providers families hire with their children’s public education dollars.

Shifting government’s primary role from instructional monopoly to market regulator and supporter will require operational changes. Families will be able to choose from a plethora of instructional options and will need access to information that allows them to make informed decisions, as well as education advisers who can help them evaluate their child’s needs and develop and implement customized education plans to meet these needs. Government will need to ensure data accuracy and truth in labeling – much as it currently ensures food labels accurately describe what’s in the package.

Third paradigm issues

Providing each child with a high-quality customized education through a more effective and efficient public education market will require public education’s stakeholders to rethink all aspects of how it operates. Here are some issues we will need to address.

Public education’s third paradigm has old roots

In 1791, Thomas Paine proposed an ESA-type program for lower-income children in “The Rights of Man.”

“Public schools do not answer the general purpose of the poor. They are chiefly in corporation towns, from which the country towns and villages are excluded; or if admitted, the distance occasions a great loss of time. Education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot; and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this, is to enable the parents to pay the [sic] expence themselves.”

Paine’s recommended funding method was, “To allow for each of those children ten shillings a year for the expence of schooling, for six years each, which will give them six months schooling each year, and half a crown a year for paper and spelling books.”

Over 150 years after Paine’s proposal, Milton Friedman proposed a similar but more comprehensive plan in 1955. Many of the third paradigm’s core ideas existed in the 1700s prior to the industrial revolution. But they were not technically or politically feasible.

Thanks to modern technology and a growing acceptance of families’ rights to direct their children’s education, these ideas are viable today. We can now provide every student with an effective and efficient customized public education. While all students will benefit from customized instruction in a more effective and efficient public education market, lower-income students will benefit the most because they have historically been the most underserved by the current government monopoly. Underserved groups always benefit greatly when the markets they rely on for essential goods and services are more effective and efficient.

Public education’s transition to its third paradigm is happening faster in Florida than in other states. Over 500,000 students using ESAs is rapidly improving Florida’s public education market. Floridians are seeing in real time the creation of a virtuous cycle between supply and demand. More families using ESAs is encouraging educators to create more innovative learning options, which in turn is causing even more families to use ESAs, which in turn is causing even more educators to create more learning options. These rapidly expanding options increase the probability that all students, but especially lower-income students, can find and access learning environments that best meet their needs.

Public education’s first paradigm shift took about 100 years to complete (1830-1930). This second transition began around 1975 and will likely also take about 100 years to complete nationally. Like all paradigm changes, this one is proving to be a long slog. But larger societal changes will help ensure this transition’s success.

Perun, the rock star of Australian defense economists doing awesome hour-plus hour PowerPoint presentations on YouTube, recently did two such presentations on “game-changing” weapon systems in the ongoing Ukraine-Russian war. Perun observed:

It seems like every time a new weapon system, be it Russian or Western, is sent to Ukraine, there are always going to be at least some voices in the media that amp this thing up as the next great game-changer, the system that will finally change the dynamics of this long and bloody war. For some systems the hype dies out, whereas for others it builds and builds until eventually the system arrives in Ukraine, and reality and expectations finally collide.

Some get to Ukraine and turn out to be utter disappointments. Others turn out to be solid, useful performers that do the job they were intended to do, but don’t exactly quickly or efficiently move the needle. And others swing in like a damn wrecking ball and on their first day of operations wreck two Russian airfields and deal the Russian aerospace forces their worst single day defeat since they were the Soviet Air Forces during the Second World War.

Inspired by the great Perun, we will here rank policy interventions designed to increase family options in K-12:

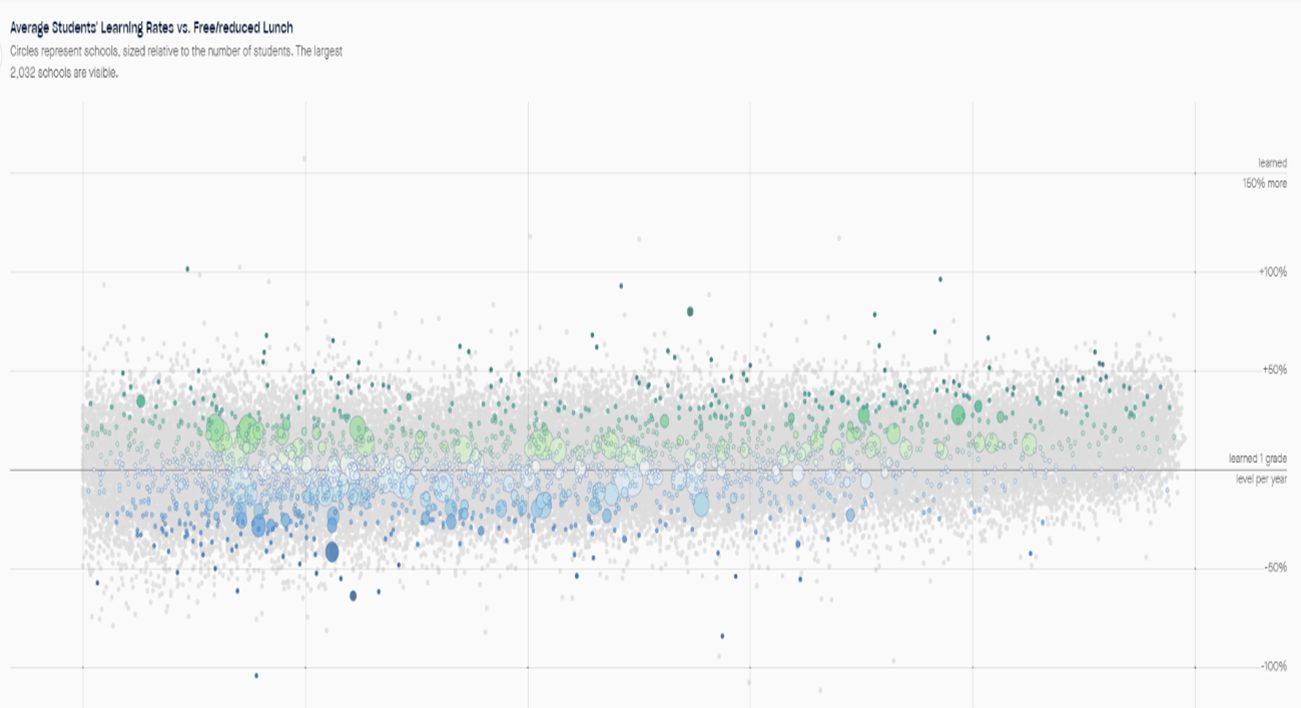

Magnet Schools: Introduced in the 1970s in the hopes of reducing racial segregation in public schools. Below is a placement of every magnet school in the nation with data included in the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project on Grades 3-8 academic growth:

That’s a lot of schools, but their average rate of academic growth is approximately equal to the nation as a whole (half above and half below the “learned one grade level in one year” line. There are many fantastic magnet schools, but the system suffers from a fatal flaw: the schools are ultimately under the control of elected school boards. Many magnet schools have waitlists of students, but districts, for the most part, do not replicate or scale high-demand schools. Unless someone can demonstrate otherwise, let’s assume that Political Science 101 is controlling here and the people working in other district schools don’t want to scale high-demand magnet schools for the same reason they dislike other forms of choice: they view it as a threat. RANKING: TAME HOUSE PET

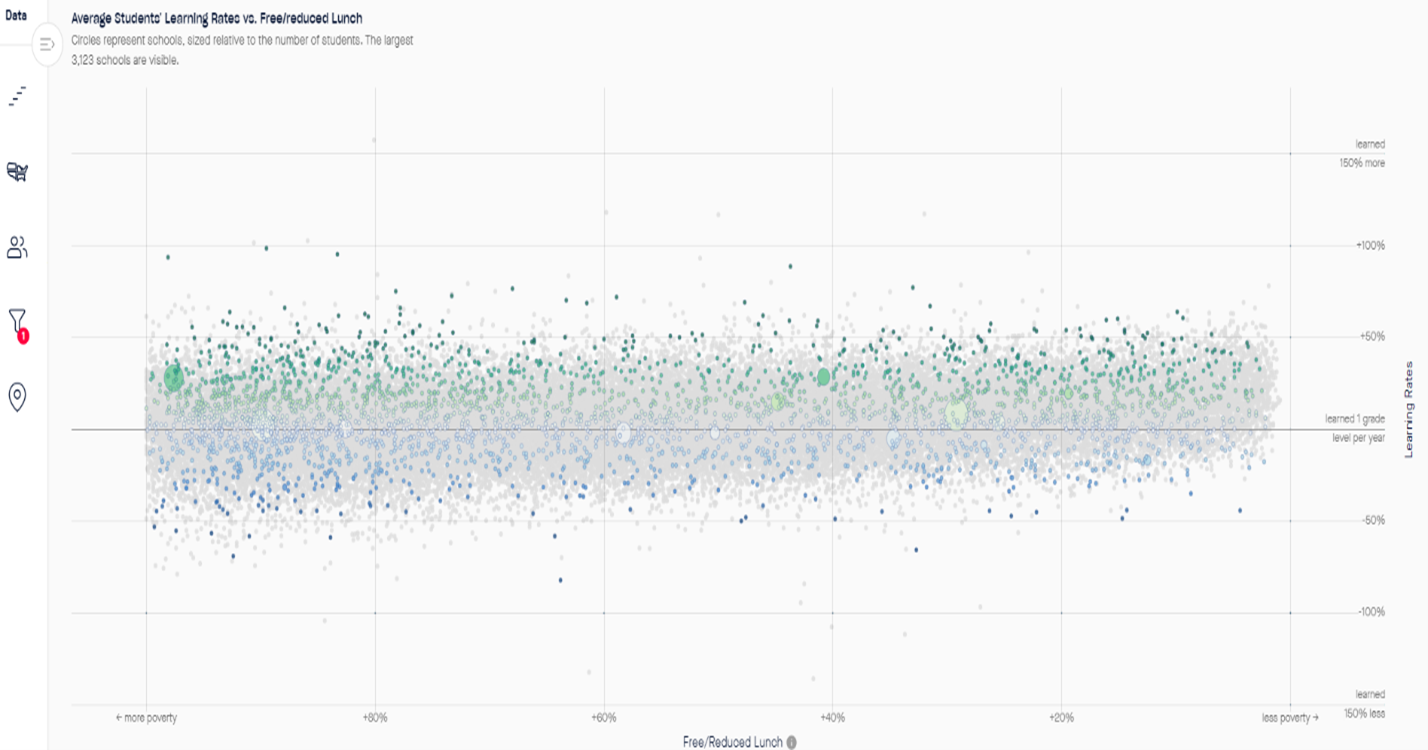

Charter Schools Introduced in the early 1990s by Minnesota lawmakers, charter schools eventually overtook magnet schools in numbers of schools, as you can see in the same chart as above for charters nationally:

Charters were the leading form of choice for years after their debut, but more recently, it has become sadly clear that they suffer from a problem not terribly dissimilar from magnet schools: a political veto on their opening. Sometimes this veto is delivered by the same districts that fail to replicate high-demand magnet schools, in other instances, it happens because of Baptist and Bootlegger coalitions controlling state charter boards. What the Baptist and Bootleggers started, higher interest rates, building supply chain issues and the death of bipartisan education reform seems to have finished. RANKING: Varies by state but mostly TAME HOUSE PET

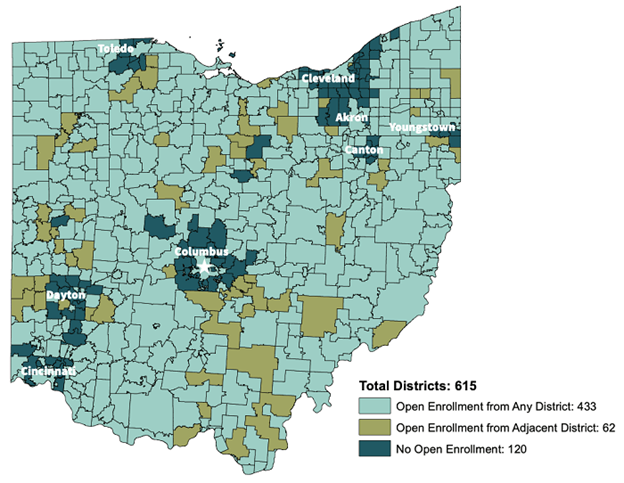

District Open Enrollment: Potentially an immensely powerful form of choice, but one which only realizes that potential if other forms of choice create the necessary incentives to get districts to participate. In most places, it looks far too much like this:

See any fancy suburbs willing to take urban kids in this map? Me neither. RANKING: Varies by state but mostly TAME HOUSE PET, could grow to become much, much more

School Vouchers/Scholarship Tax Credit: The modern private choice movement debuted in Wisconsin in 1990, the year before the first charter school law passed in 1991. Voucher adoption proceeded more slowly than charter school laws, and one of the accomplishments of the voucher movement may indeed have been to make charter schools seem safe by comparison. Scholarship tax credits, first passed in Arizona in 1997, expanded around the country more quickly than vouchers. While lawmakers passed several voucher and scholarship tax credit programs, few of them were sufficiently robust to perform critical tasks such as spurring increased private school supply, which requires either formula funding or regular increases in tax credit funding.

Scholars performed a tremendous amount of research on voucher and tax credit programs, and those programs led directly to the creation of education savings accounts (discussed next). Overall, however, these programs did not in and of themselves move the needle, although at times, the deployment of strong private and charter school programs did move the needle. RANKING: Vital Intermediate Step

Education Savings Accounts: First passed by Arizona lawmakers in 2011 and going universal only in Arizona and West Virginia in 2022, ESA programs remain a work in progress. The flexibility of accounts contains the prospect of a less supply-constrained form of choice, less dependent upon the creation of one-stop shopping bundles known as “schools.” The largest first-year private choice programs have all been recently passed ESA programs, which seems promising. ESAs, however, have yet to become a teenager, and the technologies necessary to administer them at scale remain an evolving work in progress. RANKING: Promising but To Be Determined

Barely Off the DRAWING BOARD PLATFORM

Personal Use Refundable Tax Credits: Older but tiny programs exist that deliver small amounts of money and accomplish little. Oklahoma passed a more robust program of this type last year, but it remains far too early to draw any conclusions. RANKING: Totally TBD

Homeschooling:

The homeschool movement has grown quickly is sufficiently organized to make lawmakers think long and hard before starting a quarrel with its supporters and has become more accessible with the advent of homeschool co-ops, which provides a measure of custodial care. RANKING: Wrecked two Russian airfields on the first day of deployment, unclear how high the ceiling will reach.

Conclusion: You should be seeking a combined arms operation in your state rather than a panacea-like super-weapon system that will deliver instant victory. You will know you are winning when your fancy, suburban districts start taking open-enrollment students. You will never achieve this with means-tested or geographically restricted private or charter school programs.

Nearly half of all parents are seeking new schools for their children in the 2023-24 school year. The data comes from a new survey by National School Choice Week, which found that 45.9 percent of parents want to enroll their child in a different learning environment this fall.

Of those parents, about 17 percent are still considering their options; 13 percent enrolled their student in a new school; 8.4 percent applied, and 7.5 percent chose homeschooling. That leaves 54 percent of parents keeping their child in their current school.

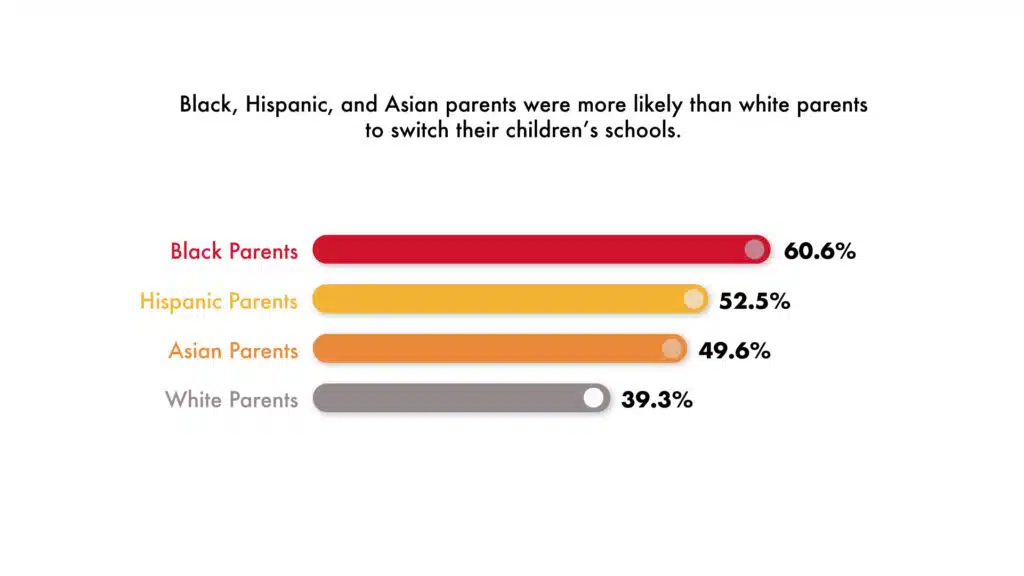

Though just under half of all respondents wanted to enroll their student in a new school, minority parents were far more likely to seek options than white ones. Black parents (60 percent) were far more likely to search for new school options than white parents (39 percent). Most Hispanic parents (53 percent) also sought new options.

Despite the large number of parents who are seeking to change schools, many thought schools were as good as or better than last year. About 45 percent of parents thought their student’s education was better than last year; 34.4 percent thought it was about the same and just 20.5 percent thought it was worse.

Despite the large number of parents who are seeking to change schools, many thought schools were as good as or better than last year. About 45 percent of parents thought their student’s education was better than last year; 34.4 percent thought it was about the same and just 20.5 percent thought it was worse.

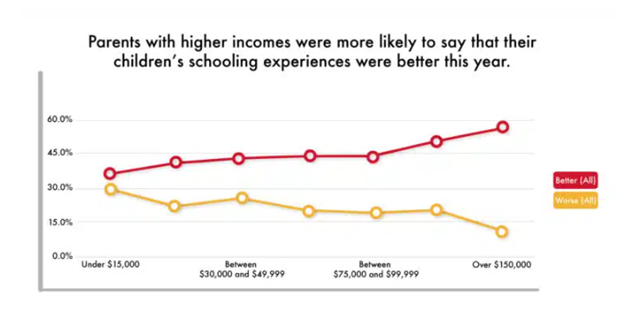

Wealthier parents, not surprisingly, were more satisfied with their educational choices than lower income parents.

The survey, by National School Choice Week, was conducted in May 2023 with more than 2,400 parents responding. Check out the full survey here.

North Hollywood High School Zoo Magnet in North Hollywood, Calif., is the 2023-23 recipient of Magnet Schools of America’s Dr. Ronald P. Simpson Merit Award of Excellence. The school is recognized by the American Association of Zookeepers as one of six high schools in the nation partnered with a working zoo.

Magnet Schools of America, a national nonprofit education association that represents more than 4,340 magnet schools serving nearly 3.5 million students across 46 states and the District of Columbia, named two Florida educators as awards recipients at the 2022-23 National Conference on Magnet Schools.

Pasco County Schools superintendent Kurt S. Browning is the association’s School District Superintendent of the Year. Browning has been the driving force behind an education choice transformation in the district, implementing innovative magnet programs at all grade levels.

The group praised Browning for providing the appropriate support to ensure quality, equity, and success for the district’s magnet programs.

The association’s website notes that leadership, commitment, and involvement are the three descriptors that capture the essence of what the group seeks in candidates for MSA Superintendent of the Year. Eligible candidates must have served as superintendent within the district in which they are being nominated for two years; must be a member of Magnet Schools of America at the time of nomination; and must include a letter of nomination in their application packet.

The organization named Daniel Mateo, an assistant superintendent for Miami-Dade County Public Schools, National Magnet School District Administrator of the Year. The group praised Mateo for his deep understanding of the unique needs and challenges of magnetMSA, a national nonprofit professional education association whose members are schools and school districts.

Nominees for Administrator of the Year must embody leadership, support and community. They must have served as a district level magnet administrator for a minimum of two years and be an active member of Magnet Schools of America at the time of nomination.

“These awards are a significant achievement for all magnet schools,” said Ramin Taheri, CEO for Magnet Schools of America. “All of our award recipients competed with a large number of schools and individuals. We are honored to have acknowledged their great work.”

Other 2022-23 award recipients include:

If a lottery on admissions were imposed at Irma Lerma Rangel Young Women’s Leadership School in Dallas, its majority Hispanic population would change significantly.

Editor’s note: This commentary is an exclusive to redefinED from Sean-Michael Pigeon, who recently graduated with a B.A. in political science from Yale University. He works as a journalism mentor at a magnet school in New Haven, Conn. His writing has appeared in USA Today, the Washington Examiner and the Washington Times.

The number of magnet schools has grown steadily over the last two decades, further increasing the control parents have over their child’s education. Many argue the most important point of magnet schools is that they allow parents to choose where and how their child is taught.

But in response to recent critiques, selective magnet schools have begun restricting enrollment by implementing zip code quotas. Not only does this cut against the goal of magnet schools; its focus is misguided.

One of the critiques levied at magnet school is that magnet schools are not diverse enough, either racially or economically. This is an important criticism for magnet schools to address, given that they were implemented in part to help desegregate school systems.

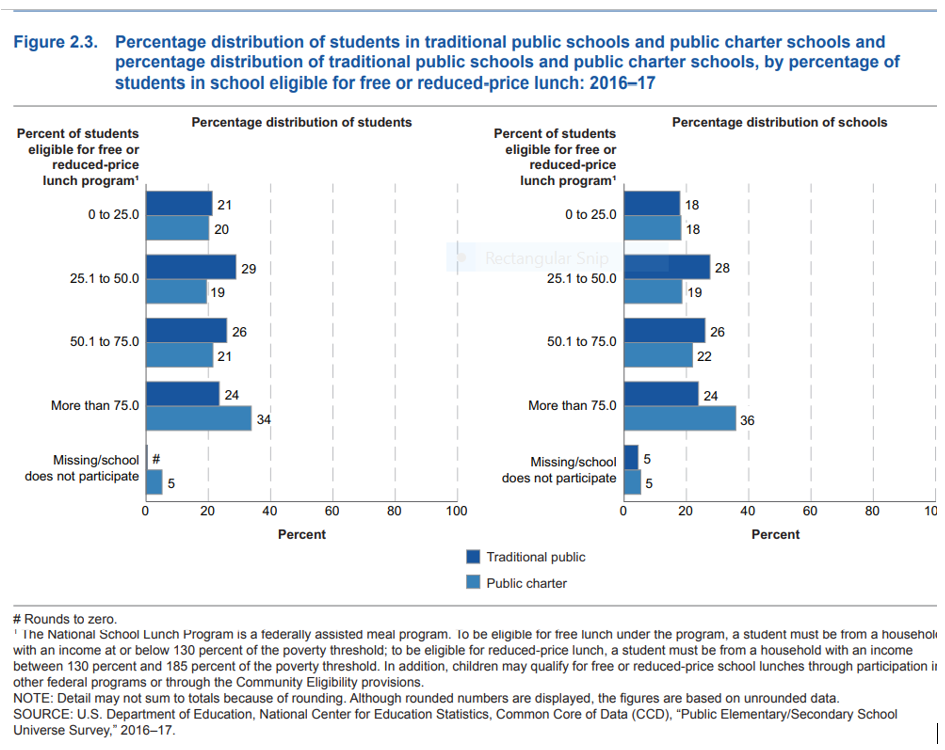

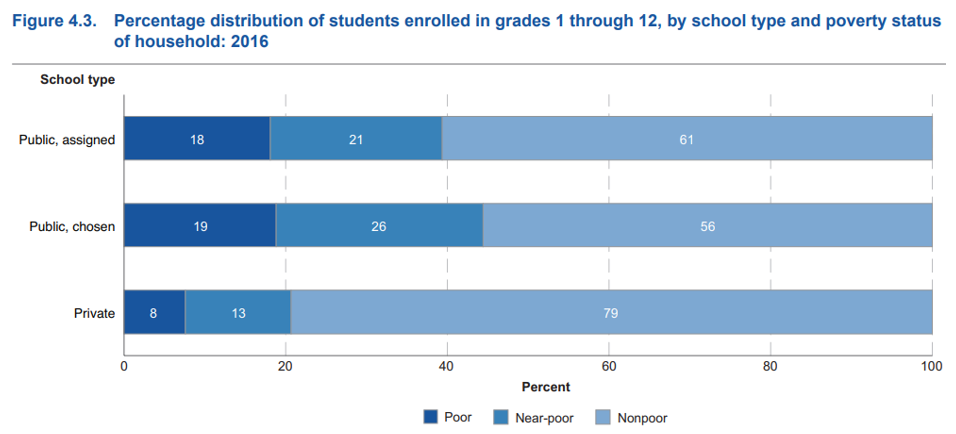

Yet the most recent evidence suggests magnet schools incorporate more ethnic minorities than traditional public schools or private schools. A 2019 U.S. Department of Education report found that a higher percentage of public charter school students were Black or Hispanic (See Figure 2.3.) In this case, “public charter” includes both magnet schools and charter schools. The report also found that “chosen public schools” had a higher percentage of poor and “near-poor” students than either traditional public schools or private ones (Figure 4.3).

This means there is no evidence that magnet schools, on average, do a better job of integrating different racial and socio-economic communities than either assigned public schools or private schools. Nevertheless, certain highly selective magnet schools have come under fire for using test scores to determine whether a student is admitted.

This means there is no evidence that magnet schools, on average, do a better job of integrating different racial and socio-economic communities than either assigned public schools or private schools. Nevertheless, certain highly selective magnet schools have come under fire for using test scores to determine whether a student is admitted.

Some parents argue that changing magnet schools’ admissions to a lottery system is long overdue. It is true that the student body of Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (the top high school in the nation, and a magnet school), skews disproportionately Asian. However, there are many minority-majority magnet schools that also are high-performing magnets.

For example, Irma Lerma Rangel Young Women's Leadership School (ranked No. 15 in the nation and No. 2 in Texas) has a student body that is overwhelmingly Hispanic, at 79%. If a lottery were implemented for Irma Lerma’s admission based on Dallas County, which is majority white, the ethnic makeup of the student body would change significantly.

Equity advocates should be wary that their efforts do not undermine the ability of magnet schools like Thomas Jefferson and Irma Lerma to nurture a school environment that has proved effective. Just because a school has a minority-majority student population, it doesn’t necessary follow that its admissions process needs dismantling.

We do not need to imagine what instituting racial quotas would do for magnet school admissions. Take, for example, University High School of Science and Engineering, a magnet school in Hartford, Connecticut. To promote desegregation and racial equality, the school is required to limit Black and Hispanic enrollment to under 75%. Connecticut courts have upheld the policy that schools like University High cannot decrease the percentage of white students required for diversity, causing widespread frustration.

One city mom was devastated that her son could not attend University High. “I was told,” she says, “‘Well, white kids from the suburbs have to apply for him to get in.’”

A recent lawsuit lobbied by Virginia parents that argued the new practices set up by Thomas Jefferson High School purposefully discriminated against Asian Americans was allowed to proceed. While those parents await the outcome, we must ask why parents must appeal to the courts to send their children to a school they would otherwise be qualified to attend.

Chosen public schools, like magnets, have proved effective in achieving learning goals while serving more minority and low-income students than any other form of schooling. Throughout the difficult 2020-21 academic year, many magnet schools led the way in transitioning to virtual learning. Other magnet schools helped students deal with mental health problems by crafting innovative solutions to isolation.

Barring high-performing and/or willing students from attending a magnet school simply because of where they live or their ethnicity is antithetical to the very point of such schools. It would be foolish to sacrifice the success of magnet schools across the country to target a problem not in sight.

Since Alberto Carvalho became Miami-Dade County Public Schools superintendent a decade ago, the number of charter school students in his district has tripled to nearly 70,000, while the number of low-income students using state scholarships to attend private schools has jumped five-fold, to 26,272. Parents in America’s fourth-largest school district now send their children to 570 non-district schools that didn’t exist or weren’t accessible 20 years ago.

So what’s a big district to do?

In the case of Miami-Dade, it’s ride the wave.

In a videotaped address for the American Federation for Children conference in May, and released by AFC Tuesday, Carvalho turned to a metaphor he’s used to powerful effect a few times before (see here and here):

“We anticipated this tsunami as it was approaching, and we made a determined decision,” says Carvalho, the National Superintendent of the Year in 2014 and National Urban Superintendent of the Year in 2018. “We decided and recognized that trying to swim under that tsunami of choice would only bring about our own demise. If we decided to outrun it, we would lose. If we allowed quite frankly to let choice be the trademark of others rather than ourselves embracing it, we would not be participants in the educational process of our students.

“So we embrace choice. We recognized that choice was powerful to every single community, every single family, every single child. So we developed a choice portfolio unlike any in the country today.”

Sixty-one percent of Miami-Dade students are enrolled in district choice – magnets, career academies, “international” programs like International Baccalaureate and Cambridge, etc. – up from 30 percent 10 years ago. Add charter schools and choice enrollment reaches 69 percent. Throw in private schools and it tops 70 percent. For context, consider that in Florida as a whole, 47 percent of students in PreK-12 now attend something other than assigned district schools.

Those who applaud the district’s theory of action don’t think it’s coincidence that academic trend lines are rising as choice is expanding. Among other notables, the district earned an A rating for the first time last year; hasn’t had an F-rated school in two years; and was a standout on the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress.

“School systems of today, that rely and bank on one single approach to deliver education to their students, are losing the potential of choice,” Carvalho says in the video. “They’re losing the powerful relevance, rigor and relationships that choice brings to school. Our choice is an umbrella approach that reflects the ambitions, the dreams, the aspirations and quite frankly the opportunities that every single kid, regardless of the zip code they’re born into, should have. This is no longer a privilege. This is a right every single child in America must have.”

As fate would have it, Education Next also put a bit of a spotlight on Miami-Dade this week, with Paul Peterson, director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard, interviewing yours truly about the district for The Education Exchange podcast. At the risk of jinxing both, I said Miami-Dade may be to big urban districts what the Tampa Bay Rays are to Major League Baseball: Low-cost (relatively speaking), innovative, fun to watch – and maybe even thriving amidst the competition.

Editor’s note: This feature originally appeared in redefinED just over five years ago on Jan. 22, 2014. At that time, the school served 270 students from kindergarten to eighth grade. Today, its award-winning program offers two tuition-free schools in Tallahassee, the second serving kindergarten through fourth-grade students. It maintains its status of being among the highest ranked schools in Leon County and is in the top 10 percent of schools in the state based on Florida School Rankings. It also has been recognized as one of 10 excellent charter schools in Florida by the Florida Charter School Conference.

Teacher Julie Sear looks on as her students at The School of Arts and Sciences in Tallahassee, Fla. test out a Rube Goldberg contraption they created.

Julie Sear is the lone science teacher at The School of Arts and Sciences, a K-8 charter school in Tallahassee. It’s trim and modest, a clutch of red and yellow brick nestled among oak-draped hills. There’s no library, no gym, no lunch room, no computer lab. The school is so unassuming and half-hidden beyond all the moss, even many locals don’t know much about it.

Which is too bad for them. Last year, 95 percent of Sear’s students passed the state’s eighth-grade science exam (it’s only given in fifth- and eighth-grade). That’s double the state average. Only 29 of the state’s 600-plus middle schools managed a pass rate above 80 percent. Only 10 cleared 90 percent.

It’s true the demographics for the 270 students at SAS aren’t the most challenging. Forty-one percent are minorities, 21 percent are eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch. The state average is 59 percent for both. But it’s also true SAS leaves more affluent schools in the dust, including three in the same district where science pass rates came in at 58, 66 and 75 percent.

What makes the difference?

Sear, 42, is a 14-year teaching veteran who taught in district schools before she joined SAS, for less pay and no tenure, in 2006. She’s a Midwesterner with a biology degree, a resume that includes six years on a boat and enough proud geek in her to wear a shirt that says, in Star Wars font, “May the Mass Times Acceleration Be With You.” (Physics joke!)

Ask her the difference-maker question, and she offers a list.

For starters: independence, autonomy, flexibility. Unlike many district schools, there is no pacing guide at SAS, no rigid calendar that dictates what must be taught and when. Asked a week before a reporter’s visit what she’d be teaching that day, Sear emails back: “I can’t plan that far ahead!!” “I have total control,” she says in an interview. “I look at all the standards and I get to say where I’m going to teach things, and how I’m going to teach it.”

Then, there’s this: SAS is small and close-knit and … nimble. It was founded in 1999 by teachers and parents. It’s not bound by convention. Sear has 88 students in classes that include sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders. That means a wider range of skill level. But it also means more familiarity with how students learn, where they’re coming up short and what can get them up to speed. “I got a pulse on them that is really strong,” Sear says.

SAS is also tough to get into. Not because of special admission standards (beyond living in the district, there are none), but because of demand. Every year, more than 200 students apply for 15 to 20 open slots, leaving the school with 750 to 1,000 on its waiting list. That, Sear says, leaves SAS teachers with leverage many district teachers don’t have.

***

A Matchbox car. A tack taped to its hood. A trio of middle school boys.

In Sear’s first period, a project: Make a Rube Goldberg contraption with at least five energy transfers. Boy one nudges the car towards a balloon, which butts up against one of those pendulums with a series of spheres on strings, which is next to another toy car, which is tracked towards a marble, which is then supposed to dribble off the edge of the counter into a cup on the floor. Car rolls. Balloon pops. Pendulum swings. The second car rolls, but stalls before it can ram the marble.

“Not enough force,” Sear says. “What can you do different?”

Next try: Car rolls. A bigger balloon pops. The pendulum swings. The second car rams the marble. The marble rolls … and rolls … and (hold your breath) … stops at cliff’s edge. Ahhhh, the boys groan.

But they smile, too.

“We fail a lot,” shrugs seventh-grader Mahir Rutherford. “That’s just part of the experiment.”

Sear’s class at SAS is noteworthy for what it doesn’t have. No textbooks. No lavish equipment. No admonitions to get this right because it’s going to be on the FCAT (the dreaded state test). No fear of failure. And usually, no force-fed information.

Sear’s class at SAS is noteworthy for what it doesn’t have. No textbooks. No lavish equipment. No admonitions to get this right because it’s going to be on the FCAT (the dreaded state test). No fear of failure. And usually, no force-fed information.

“Who agrees? Who disagrees?” Sear says during a class debate. The topic: data reliability in an experiment involving the speed of toy cars and marbles on very short ramps. She points to a girl at random: “Defend.”

“I’m not going to tell you any right and wrong answers,” Sears says a few minutes later, as she invites others to offer explanations in front of the class. “You’re going to have to deal with that.”

They do. And they love it. Asked what accounts for their success, the students offer many of the same answers as their teacher. Many were in district schools before SAS. Many gush about the school they're in now.

“We do more hands on. It’s not like, ‘Okay, get your textbooks.’ ”

“Instead of just memorizing things, we learn how to figure them out.”

Several echoed variations on the leverage theme.

“If we don’t do something with enough enthusiasm, Miss Julie reminds us that we chose to be here.”

***

Florida has yet to get the credit it deserves for pace-setting gains in reading and math. But it hasn’t gotten the same traction in science. Some school choice supporters see potential for growth there.

For example, charter schools, freed from the complications of collective bargaining, theoretically could embrace meaningful differential pay – a potentially useful tool for luring and keeping STEM teachers. There’s also a small but growing number of charter schools, such as the high-minority, high-performing Orlando Science School, that put STEM front and center. Parents are drooling over them.

Coincidentally or not, schools of choice lead the Florida pack in science. Ten of the 29 highest-performing middle schools are charter schools. Seven are magnet schools. On the other hand, there’s no doubt some district schools excel in science, and that they too have rock-star science teachers.

In Sear’s case, then, how much of her success hinges on SAS being a school of choice in general, or a charter specifically? Is there something about charter schools or other choice schools that makes them more likely to create the conditions that maximize teaching talent?

Sear’s principal says yes. So does a parent at the school. So does one of Sear’s colleagues, a science teacher at a district school, even as he and the others acknowledge Sear would probably soar anywhere.

“I am not micromanaging her,” says the principal, Julie Fredrickson, who taught in district schools for 14 years. “Districts are more likely to feel the need to have more control.”

A charter school “takes the big boss off your shoulder,” said Susie Merkhofer, who has two kids at SAS.

In district schools “teachers tend to homogenize their curriculum,” said Charles Carpenter, a 15-year physics teacher in the district where SAS is located.

Carpenter is on sabbatical and working at Florida State University, on a professional development program that helps teachers increase their physics knowledge. He said research vouches for Sear’s approach to science instruction – yet, for reasons that befuddle him, many district schools have yet to follow suit.

***

So does Sear think it’s better in a charter school?

She won’t say yes or no. Instead, she put her thoughts down in a lengthy email, pointing to a combination of things that she says makes a difference.

To make a long story short ... our school does a fabulous job of making me feel VALUED and empowered. I feel that my efforts are appreciated, that my voice is heard, and that my opinions matter. …

Yesterday, I mentioned to you that leadership is key. I don't know if "charter" is the key. Maybe, in the charter schools led by national management companies, the small school feeling is lost in the top-down leadership. It would be interesting to find out more about the other high performing charters. Are they led through big management companies or are they more grass roots in nature? Does that make a difference?

Basically, does teacher value/empowerment equate to successful teaching and learning?

And as a result, when teachers feel valued/empowered, are we able to help the kids feel more valued/empowered?

Very interesting way to start my morning!