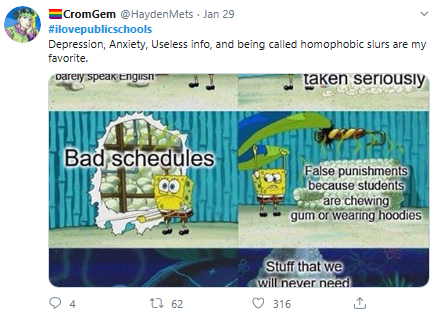

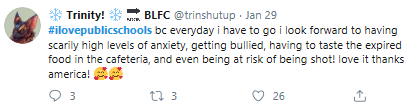

Recently, the hashtag #ilovepublicschools trended on Twitter, but perhaps not in the way intended.

Recently, the hashtag #ilovepublicschools trended on Twitter, but perhaps not in the way intended.

My intent in sharing a sample of what happened when public school students and parents began weighing in is not to bash public schools. I am a public school graduate, my mother worked in the public school system, and all three of the Ladner children have attended public schools. Many people do, in fact, love their public schools, and you can see evidence of that if you visit the hashtag.

But you also will hear from people who are miserable in their public schools.

Several of the #ilovepublicschools participants wrote about being bullied because of their sexual preference or disability status.

Again, I do not present these examples as a gratuitous attack on public schools, but rather to make the point that a great many families desperately need new schooling situations.

A scroll through #ilovepublicschools makes it clear just how profoundly misguided the current media campaign in Florida is to persuade companies not to make donations to scholarship programs. Students suffering from bullying, anxiety and depression often desperately need a new school. LGBTQ students are disproportionately the victims of such bullying. Tax credit scholarships are given to students in an entirely neutral fashion, and LGBTQ students are now using tax credit scholarships to attend schools that work for them.

Students like Elijah Robinson, for instance, who was featured on redefinED in October.

A successful campaign to dissuade companies from donating to the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program will defund the scholarships of thousands of desperate students, students in situations like Elijah’s, and indeed, Elijah himself. If anyone can tell me Elijah Robinson should have been denied the opportunity to attend The Foundation Academy after having been relentlessly bullied at his previous school, the comment section awaits your explanation.

I fear there are people in our society so filled with hate for education choice programs that they would look Elijah Robinson in the eye and tell him, “You can no longer attend The Foundation Academy because of the decisions of unrelated third parties. Go back to the school whose students and staff drove you to the brink of suicide.”

I sincerely hope, dear reader, that you are not one of those people. If you are, I hope that God will shine a light into your soul that will allow you to rediscover your humanity.

Alicia Davis, left, and her wife, Kaitlin Davis, help their 9-year-old twins, Brian and Leah, with their homework. Like Alicia and Kaitlin did when they were students, Brian and Leah are benefiting from education choice options available to Florida families.

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Alicia Davis needed a fresh start after a storm of challenges – including being a teen mom – overwhelmed her in high school. Kaitlin Davis needed a safe place after kids in her assigned middle school tormented her over her sexual identity.

They are adults now, happy, married, and raising a family. For their 9-year-old twins, Brian and Leah, who endured bullying in kindergarten, the Davises turned almost instinctively to the kind of education choice options that are available to parents in one of the most choice-rich states in America. They found a private school, courtesy of a state scholarship, that knew how to navigate their children’s “disabilities” while also understanding their pain.

Brian and Leah Davis are making steady progress at The Foundation Academy. They are pictured here with one of their teachers, Donna Anderson.

When you have options, “You don’t have to sacrifice being emotionally okay to have a good education. You don’t have to sacrifice a good education to be emotionally okay,” said Kaitlin, now 23. “You can have both.”

(Watch the video at the end of this post to hear Alicia and Kaitlin tell their story in their own words.)

Kaitlin and Alicia, 25, have been together five years. They married last year. Kaitlin is a collision adviser at a Toyota dealership. Alicia stays at home so she can best care for their 5-year-old, Emmett, who has diabetes. Kaitlin is pregnant with their fourth child. Their cozy house in a working-class neighborhood is 20 minutes from the school they consider a lifeline.

The Davis’s experience with public education is fast becoming the new normal in Florida. A generation ago, about 10 percent of K-12 students in Florida attended something other than assigned district schools. Today it’s more than 40 percent.

“Multiple choice” families with children enrolled in two or more options are not hard to find. It won’t be long before the same is true of families like the Davises.

***

Alicia Davis didn’t do well in district schools. ADHD made her unruly. Medication for it left her sleepy. Other issues piled on. Making friends was a struggle when her family moved from small-town Ohio. So was coming to terms with her sexual orientation. So were family members who didn’t understand.

In 10th grade, Alicia got pregnant. She didn’t listen to those who advised her to end the pregnancy; abortion violated her belief system. She didn’t listen to dark voices in her own head, either. At one point, she said, she stood on a third-floor apartment balcony for 45 minutes before crawling away. “I said, ‘This isn’t how my life should be for my babies,’ ” she said through tears. “So I talked myself down.”

School, though, didn’t get easier. In her junior year, Alicia was told she couldn’t graduate because she was too far behind to catch up. That’s when her mom went searching for options. She discovered Alicia could get a McKay Scholarship, an education choice scholarship for students with disabilities. By coincidence, Nadia Hionides, the principal of an inclusive, faith-based private school called The Foundation Academy, came calling. Alicia’s school had alerted her that Alicia might benefit from something different.

She did. “Nadia never said no, she never turned her back, she never said I couldn’t do anything,” Alicia said. The non-judgmental atmosphere was key. “Nobody cared that I was a teen mom … nobody cared that I was open with my sexuality,” she said.

Alicia and her classmates worked on a project about coping with schizophrenia. For the community service component, she volunteered at a mental health resource center.

Without all the distractions, she said, she could finally focus on learning.

***

Kaitlin Davis “came out” in eighth grade. The bullies pounced. They called her names, bumped her in the halls. Kaitlin wondered if it would ever end. She didn’t fight back because she didn’t want to risk a suspension. She didn’t tell school officials because, “I felt like it was my battle.”

Silence took its toll. “I was depressed,” she said. “I stayed home from school a lot. I would make up things. I was quote unquote sick a lot.”

Kaitlin worried high school could be as bad if not worse, because she and the bullies were zoned for the same school. By coincidence, Kaitlin’s brother had been attending The Foundation Academy with a McKay Scholarship. Her parents knew it was warm and welcoming.

Kaitlin was not eligible for education choice scholarships. Her parents’ income was too high for the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students, and she didn’t have disabilities to qualify for McKay. Today, she would be eligible for two, newer state scholarships: the Family Empowerment Scholarship for working- and middle-class families, and the Hope Scholarship for bullying victims. (The FTC, FES and Hope scholarships are administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Kaitlin said it hurt her parents financially to pay tuition. Mom’s a nurse. Dad’s a Navy vet and a welder by training. But for a year they found a way. The next year, Kaitlin enrolled in Florida Virtual School. She was in a hurry to get to work, and total immersion in FLVS allowed her to complete two years of schooling in one. She returned to The Foundation Academy for her senior year, to enjoy prom and other rituals of a more typical school. Hionides offered a tuition break in return for Kaitlin’s work as a file clerk and camp counselor.

Had it not been for the school, Kaitlin said, “I would have still been in my shell.”

And probably, she said, a dropout.

***

Brian and Leah have speech impediments, which at times can make them a little hard to understand. But Brian’s kindergarten teacher, Alicia said, heard a kid who couldn’t learn.

The Davis twins’ confidence has increased at The Foundation Academy.

When Brian struggled, the teacher “put him off to the side,” Alicia said, which gave his classmates an opening to pick on him. “Once it started,” Alicia said, “it just never stopped.” On a bus ride home, both Brian and Leah, who defended her brother, ended up with knots on their heads the size of half dollars.

When Alicia complained, she said school officials told her to file a police report. (She refused, given the bullies were 5-year-olds.) When problems with the teacher persisted, she said district officials suggested a transfer. But other district schools either had no openings or other reasons the twins couldn’t be accommodated.

In desperation, Alicia again turned to The Foundation Academy and McKay Scholarships. At the time, she and Kaitlin were living in a neighboring county. But with Brian and Leah in a safe school, the commute – more than an hour each way – was worth it.

Now the twins are in third grade and making steady academic progress. One of their teachers said Brian’s confidence makes him especially smooth at public presentations, and Leah’s makes her a natural leader.

“That school is like a giant family,” Alicia said. And for her and Kaitlin’s family, it has been for two generations now.

It feels, she said, like home.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=GHOSmEETzvE

Albert Einstein Academy opened in August 2018 to serve mostly LGBTQ high school students in metro Cleveland. Nearly 40 students enrolled and another 15 signed up to enter as ninth-graders this fall. About 80 percent of the students at the charter school identify as LGBTQ.

Sixteen-year-old Channing Smith of Tennessee killed himself after classmates circulated sexually explicit messages he exchanged with another boy. Fifteen-year-old Nigel Shelby of Alabama killed himself after peers bullied him over his sexual identity and school officials reportedly told him “being gay is a choice.” When 9-year-old James Myles of Colorado came out at his school, fellow students reportedly told him to kill himself. Tragically, he did.

In Florida, Elijah Robinson was harassed to the edge too. But for an educational choice scholarship that gave him an option – a safe, accepting private school – Elijah, 18, said he would no longer be alive.

Channing, Nigel, James and Elijah were students in public schools. That’s not a slam on public schools. It’s just a reminder, which I wish wasn’t necessary, that far too many LGBTQ students are tormented in far too many schools of all types.

Elijah Robinson, 18, a student at Foundation Academy in Jacksonville, Fla., experienced severe bullying at his assigned public school. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

It’s also a plea. LGBTQ students are two to three times more likely to experience bullying than non-LGBTQ students. I hope all of us who want to end that hostility will think twice about a narrative, recently buoyed by legislation filed in Florida, that casts programs that provide private school options as though they are inherently part of the problem. If the goal is ensuring the safety and affirmation of LGBTQ students – and not simply the tarring of educational choice – that doesn’t make sense.

Please consider what LGBTQ students say. According to the most recent survey by GLSEN, 72 percent of LGBTQ students in public district schools said they experienced bullying, harassment and assault due to their sexual orientation, compared to 68 percent of LGBTQ students in private, religious schools, and 60 percent in private, non-religious schools. For bullying, harassment and assault based on gender expression, the numbers in those three sectors were 61, 56 and 58 percent, respectively.

All those numbers are horrifically high. All lead to dark places. LGBTQ students are three times as likely as non-LGBTQ students to suffer from depression or anxiety. They’re twice as likely to experiment with drugs and alcohol. While 15 percent of non-LGBTQ high school students considered suicide over the past year, 40 percent of LGBTQ students did.

Educational options are not an antidote. But they can help.

In Florida, recent scrutiny over a relative handful of private schools that are not LGBTQ welcoming ignores a key point. Students are not assigned to those schools. Their parents can enroll them elsewhere. That’s often not the case for LGBTQ students suffering in assigned public schools. Elijah Robinson endured nearly two years of abuse in his assigned school before a scholarship gave him a way out. “If I had stayed,” he said, “I honestly think I would have lost my life.”

In Ohio, educators concerned about LGBTQ bullying in district schools opened a charter school for LGBTQ students. To be sure, some supporters had mixed feelings. As one parent told me, “We’re saying, ‘You’re so different, you need your own school’.” On the other hand, for many students at this school, having an option was literally a matter of life and death. “There’s a need,” said Henry, a transgender student who considered suicide in fifth grade, “for a school where people can feel like they belong.”

One day, I hope, all schools will be safe and affirming. In the meantime, it’s unconscionable to trap Elijah, Henry or any other student in any school that isn’t.

Elijah Robinson, 18, was relentlessly bullied in his prior school because of his sexual identity but is back on track emotionally and academically thanks to The Foundation Academy, a private school where he’s found a safe haven. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – Every day, they cut him with slurs. Almost every day, they tried to block him from the boys’ locker room. For Elijah Robinson, a soft-spoken kid with mocha skin and almond eyes, the harassment at his high school was cruel punishment for his sexual identity.

It started in ninth grade and continued through most of 10th. It eventually turned physical, with boys pushing and kicking him, hoping to provoke a fight.

At some point, Elijah said, the bullying made him too “scatterbrained” to focus on academics. His A’s and B’s fell to F’s. But bad grades were the least of it.

To hear Elijah's story in his own words, click on the video link at the end of this story. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

The bullying led to depression. Depression spiraled into a suicide attempt.

Once Elijah got out of the hospital, his mom decided to take him out of the assigned public school that had become his nightmare and send him to a place called The Foundation Academy. A friend assured Elijah’s mom that the eclectic little private school was warm and welcoming – to all students.

To pay tuition, the single mother and nail salon worker secured a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students. Funded by corporate contributions, the scholarship is used by 100,000 students statewide, two thirds of them black and Hispanic and typically the ones who struggled the most in their prior public schools.

Without it, Elijah’s mom said, she wouldn’t have been able to afford the school.

Without it, Elijah said, he wouldn’t be alive.

“If I had stayed at my previous school,” he said, “I honestly think I would have lost my life.”

Elijah is 18 now, and a senior. The bullying is behind him. His academics are back on track.

The students and teachers at The Foundation Academy “didn’t see me as a label. They saw me for me,” he said. “I definitely am in a better place.”

Elijah’s story would be compelling any time, but it’s especially poignant now as there has been increased criticism of the scholarship program and religious schools with policies adhering to their faith.

According to the most recent survey from GLSEN, 72 percent of LGBTQ students in public district schools said they experienced bullying, harassment and assault due to their sexual orientation, compared to 68 percent of LGBTQ students in private, religious schools. For bullying, harassment and assault based on gender expression, the corresponding rates were 61 percent and 56 percent.

Those numbers speak to an urgent need for more awareness and action across all types of schools. But in the meantime, this fact cannot be ignored: The growing availability of choice scholarships has given more students like Elijah the ability to find a safe haven.

Elijah learned about The Foundation Academy’s drama program from a friend. He values the opportunity the program has given him to express himself and credits it for making him a better actor. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

Elijah is tall and thin, with a shock of hair that makes his mixed-race features even more striking. He likes to jog. He likes to read. He likes “Call of Duty,” and salmon sashimi, and fishing with his uncle. He exudes a quiet confidence that sometimes comes to those who have endured so much, so young.

Elijah thinks he was harassed in his prior school because he liked to wear girl’s jeans and sweaters and was not “acting like the stereotypical guy.” He said he didn’t fight back. Instead, he did what bullied kids are advised to do: tell the adults in charge. The teachers and administrators said they told his tormentors to stop, but they didn’t stop. Elijah said when he continued to complain, the teachers and administrators told him to “just ignore it.”

The Foundation Academy is 15 minutes from Elijah’s old school, but in terms of school culture it’s on another planet. It serves 375 students in K-12, with 86 percent using choice scholarships. Thanks to those scholarships, the school is remarkably diverse, and has served at least two dozen openly LGBTQ students.

In a 2018 story about another LGBTQ student who found refuge at the school, founder and principal Nadia Hionides noted she has a son, a brother and a niece who are LGBTQ. “We love Jesus, and Jesus loves everybody,” Hionides said. “We must affirm and accept everybody.”

Elijah isn’t sure exactly what he’s doing after graduation, but he’s planning on college and wants to be a nurse like his aunt. He likes the thought of helping people in pain. He already knows a lot about hurt and healing.

Kiwie, 14, is an eighth-grader who has endured years of turbulence in public schools because of his LGBTQ status. The only school where he briefly felt accepted was a faith-based school in Jacksonville where most of the students use school choice scholarships.

DAYTONA BEACH, Fla. – Kids walking past the classroom windows would point and yell, like kids in a zoo. “THAT’S A GIRL!” They’d grab his chest and groin, to see if the rumors were true. All day, he’d avoid the middle school restroom, to avoid boys sliding under the stall. “Dyke.” “It.” Maybe it’d have been less hellish if students were his only tormentors. One time, Kiwie got the courage to raise his hand for help, only to have the teacher enunciate the stab. “Yes, ma’am?”

“It felt,” Kiwie said, “like my heart was squished.”

Kiwie is 14. He’s an eighth grader. He faces an uphill battle to get to ninth. No child’s learning experience should be like this. Yet for Kiwie, it’s like this, year after year.

His only reprieve: Two months in a Christian “voucher school.”

***

Kiwie is slim, athletic, stylish. Round-ish frames and a black T-shirt pair with a puff of honey-brown hair. He likes lasagna and Chick-fil-A. He likes Odell and Conor McGregor. His dad is an amateur boxer. His ethnic blend – Italian, Croatian, African-American — turn heads. Maybe it’s no surprise he wants to be a model or a boxer.

Kiwie grew up in Jacksonville, 90 minutes north of Daytona. He struggled from the start in public schools. By the time he was diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD, his mom, Stella, said he’d already been held back in second grade. By then, he hated school. (For security reasons, Stella requested she and Kiwie’s last names not be used.)

Meanwhile, his gender identity was emerging. He never liked girl’s clothes. Never liked pink. “I didn’t know why,” he said. “I just knew it wasn’t me.”

By fourth grade, he was asking teachers to call him Kiwie, a pet name his father gave him. By fifth grade, he was becoming enraged when they botched the pronouns. “They didn’t care,” he said. “They thought I was just confused.”

Rage alternated with depression. At home, Kiwie would bang his head into the wall. He ran a pocket knife across his wrist.

In sixth grade, Kiwie googled “trans.” “I said, ‘Yeah, that’s me.’ ”

When he felt slighted, Kiwie began walking out of class. He flipped a table. Knocked a computer off a desk. One time, police were called. A few times, he was “Baker Acted.”

“I felt like the world was crumbling on us,” Stella said. “Why can’t they just accept him?”

***

Kasey, 14, is one of nearly 40 students enrolled this fall at the Albert Einstein Academy, a charter school serving mostly LGBTQ students in metro Cleveland. (Photo by Ken Blaze.)

LAKEWOOD, Ohio – Last June, Kasey, 14, was walking to the bus stop, en route to an LGBTQ center, when the sign came out of nowhere. It was emblazoned with rainbow colors, in a window of the block-long building that houses a warren of doctor’s offices, a Brown Sugar Thai … and now, a new school.

“Albert Einstein Academy,” it said. “LGBTQ Affirming.”

For Kasey, dreading yet more bullying in a district school, the sign might as well have said, “LIFE SAVING.”

The Albert Einstein Academy is a charter school. It opened in August to serve mostly LGBTQ high school students in metro Cleveland. Nearly 40 enrolled this fall; another 15 signed up to enter as ninth graders next fall. About 80 percent, like Kasey, identify as LGBTQ.

The school’s emergence in a leafy, Midwestern suburb has drawn little attention, but it spotlights a tangle of thorny issues. The high rates at which LGBTQ students are harassed. The fear it could get worse given a national climate growing less tolerant. The extent to which school choice can be part of the solution.

There’s a Florida connection, too. This fall, the Sunshine State began offering a private school choice scholarship for bullying victims – the first of its kind in the nation – that is drawing praise and scrutiny. Praise, because it’s giving desperate students and parents more options. Scrutiny, because while some of those options are LGBTQ friendly, others are not.

These issues aren’t black and white, but they may be life or death. Perhaps nobody understands the complications better than LGBTQ students who’ve been bullied, and whose parents now have options – even if it’s one option – they didn’t have before.

Ultimately, said Henry, an 18-year old junior at Albert Einstein Academy, who’s been in five schools in the past five years, “There’s a need for a school where people can feel like they belong.”

***

Over the past few decades, America has radically changed its attitude about all things LGBTQ. To take views on same-sex marriage as but one indicator: Twenty years ago, Americans opposed the idea 62 percent to 35 percent, according to Gallup. Now they support it, 67 to 31.

Yet for many LGBTQ students, schools are still war zones.

LGBTQ students are two to three times more likely to experience bullying than non-LGBTQ students. The most recent survey from the LGBTQ student advocacy group GLSEN, released Oct. 15, offers plenty of painful details.

Nearly 60 percent of respondents felt unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation, while 45 percent felt unsafe because of their gender expression. One in three missed at least one day of school in the past month because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable. One in 10 missed four or more days. LGBTQ students in public schools reported higher rates of hostility than peers in private schools, including faith-based schools. But it’s clear no school sector is immune.

It’s also clear the repercussions are tragic. LGBTQ students are three times as likely as non-LGBTQ students to suffer from depression or anxiety, and more than twice as likely to experiment with drugs and alcohol. Only a third report being happy. And while 15 percent of non-LGBTQ high school students considered suicide over the past year, 40 percent of LGBTQ students did.

That’s worth repeating.

Every year. Forty percent. Consider suicide.

***

Kasey is tall and slim, with kind eyes, black Converses, and enough lovable slacker aura to conjure Keanu Reeves in “Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure.” It’s hard to imagine how a kid this funny and warm could be so filled with hurt they spent middle school careening from one fight to another. But it’s a fact.

There’s the boy they popped for calling a friend a crack whore. The boy with the wire-rimmed glasses they punched so hard, metal sliced his cheek. The boy they tried to tackle after a lunchroom taunt, “tray lady,” that was meant to demean more than their long hair. (more…)