EdChoice has an interesting survey question comparing what sort of school parents would prefer (district, charter, private or home) and comparing the results to actual enrollment patterns. In 2024 it looked like this:

There is a lot happening in that chart, starting with the apparent desire of approximately 50% of the parents of district students to have their students somewhere else. Of course, a great many legal and practical constraints stand between preference and reality, which is why we have an education freedom movement and why we find so much opposition from the insecure K-12 reactionary community. Taking the surveyed demand as a part of a thought experiment around “what would it take to give families what they want?” can be illuminating. Of course, in the real world, these things change only gradually. Arizona has the highest percentage of students in charter schools at 21% or so, but it took three decades to get there for all kinds of reasons, including the need to have school space, which involved a great deal of construction and debt. We live in a world of charter and private school scarcity relative to demand, and keeping up the previous (inadequate) pace of construction may prove difficult.

Using my advanced skills acquired in the Texas public school system between 1972 and 1986, I have used this surveyed demand to calculate an implied demand for an additional 1.1 million charter school spaces. Don’t hold your breath waiting for them. It took almost three and a half decades to reach 3.7 million, and if you’ll now take a look at the first chart above, you’ll see that most of that three-and-a-half-decade period involved relatively low and almost continually declining long term interest rates between 1991 and 2021.

After 2021, both interest and building costs went up for charter school construction. Interest rates of course could go down, but they could also (gulp) go further up. A slowdown in the rate of new charter openings happened before the increase in interest and construction costs:

The little green force mystic taught us “always uncertain the future is,” but it appears to me that circumstances will require the rise of different school models that create seats sans debt. The old expression holds that God doesn’t close a door without opening a window, and the recent rise in interest rates happened almost simultaneously with the rise of pandemic pods and a la carte learning.

Was pandemic learning loss a necessary evil to create a more just society?

One teachers union representative from Richmond, Virginia seems to think so. In an interview with ProPublica, Melvin Hostman, who serves on the Richmond Education Association’s executive board, remarked that “the whole thing about learning loss I found funny is that, if everyone was out of school, and everyone had learning loss, then aren’t we all equal? We all have a deficit.”

When confronted with evidence that learning loss disproportionately affected already-disadvantaged populations, Hostman doubled down, pinning the blame on American society’s intrinsic inequities. “Now people are saying, ‘We’re going back to the way things were before,’” Hostman added. “But we didn’t like the way things were before.”

It’s worth noting that Hostman’s position is extreme and uncommon. The vast majority of educators — including those affiliated with prominent unions — are not only worried about learning loss, but also support traditional methods (like extra instructional time and targeted tutoring) of overcoming it.

However, a disturbing number of union representatives and advocacy groups see the pandemic’s aftermath as an opportunity for social and educational re-engineering. In other words, terms like “learning loss” and merit” are now considered old-fashioned at best and something far more sinister at worst.

If union representatives like Hostman want an honest conversation about reform, they have to stop trying to put lipstick on a pig. School closures were incredibly harmful — particularly for disadvantaged students who needed in-person education the most.

More specifically, learning loss, at least in the 2020-2021 school year, was by no means an inevitability. Kids didn’t fall behind because of structural inequities in the American educational system; kids fell behind because many states and districts made a conscious decision to keep them out of school for extended periods of time.

Salt Lake City didn’t even start reopening their schools until February 2021. Students in other places endured even greater turmoil — for New York City, Washington DC, and many school districts in states like California and Illinois, full reopening wouldn’t come until the 2021-2022 school year.

As a result, private schools, which were much more likely to be open for in-person instruction, saw an influx of students. The greater awareness of alternatives helped fuel parents' demand for more choices and led many states to establish or expand education choice programs.

The results speak for themselves. A Harvard study released last year, which analyzed data from more than 2.1 million students, found that school districts that employed remote learning for longer suffered a higher degree of learning loss. In contrast, students in states like Texas and Florida, which resumed in-person learning as quickly as possible, “lost relatively little ground.”

“Interestingly, gaps in math achievement by race and school poverty did not widen in school districts in states such as Texas and Florida and elsewhere that remained largely in-person,” said Thomas Kane, one of the study’s authors, in an interview with the Harvard Gazette. “Where schools remained in-person, gaps did not widen…where schools shifted to remote learning, gaps widened sharply.”

Taken to their logical end, Kane’s comments directly contradict Hostman’s claim, and confirm that America’s children’s experiences were not “all equal.” Children, many from already disadvantaged backgrounds, were kept out of school unnecessarily and suffered disproportionate learning loss as a result.

I’m not about to claim that the chaos was intentional. I’m sure most school closures were done in good faith, even though the scientific research overwhelmingly backed reopening. However, all policy choices have consequences, and these consequences were particularly severe.

Simply put, Hostman’s claim was just plain wrong. Any debate regarding what to do next must start there.

Garion Frankel is an incoming doctoral student in PK-12 education administration at Texas A&M University. He is a Young Voices contributor, and frequently writes about education policy and American political thought.

SailFuture, a private high school, started as a mentoring program for at-risk youth by teaching them maritime skills through sailing adventures. It recently was named as one of 32 semifinalists for the $1 million Yass Prize to be awarded in December.

Consulting firm Tyton Partners, in collaboration with the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust, today released a new report, Choose to Learn 2022, that looks at data collected from more than 3,000 K-12 parents and more than 150 K-12 suppliers across all 50 states in the United States.

The report finds that 52% of parents now prefer to direct and curate their child’s education rather than rely on their local school system, and 79% of parents believe learning can and should happen everywhere as opposed to in school alone. Data shows that parents want experiences that make their child happy, above all else, by reflecting their child’s interests and providing individual academic support. However, despite all parents reporting similar goals for their children, regardless of demographics, the study reveals gaps in program participation across income and race. For example, children from underserved backgrounds are nearly two times less likely to participate in learning outside of school than their peers.

Choose to Learn 2022 explores the variety of K-12 options now available to families – inclusive of both in- and out-of-school educational offerings – and how this ecosystem can better reflect families’ broader aspirations for their children. The publication follows recent findings from Tyton Partners’ School Disrupted 2022 series, which highlighted the near 10-percent decline in district public school enrollment due to the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In viewing K-12 through a broad lens, we set out to better understand the issues impacting every family, including more than forty million parents who send their children to public school,” according to Christian Lehr, Senior Principal at Tyton Partners and the lead author of Choose to Learn 2022. “Relative to issues of equity and access, our local public districts play a crucial role for K-12 families. At the same time, families crave a wide variety of learning experiences. It is in this spirit that we examined parents’ aspirations at the intersection of in- and out-of-school learning, and ask: How can the K-12 sector deliver a stronger union of academic, extracurricular, and personal outcomes for all families, regardless of life or economic circumstances?”

Based on these findings and more identified in this study, it is clear now more than ever that parents want an education centered on the needs of their child, yet there is continued work that needs to be done to bridge the gap between aspiration and reality. It is incumbent upon the K-12 system of policymakers, system leaders, and suppliers to introduce new experiences, choices, and outcomes into local school districts and catalyze the growth of programs outside of school and across all demographics.

Choose to Learn 2022 underscores the need for the K-12 system to move towards a more student-centric future and helps readers understand how to:

“We are honored to have the opportunity to drive this pivotal conversation forward, alongside our partners, the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust,” according to Adam Newman, Founder and Managing Partner at Tyton Partners. “There is a clear call for us to collectively build towards a more student-centered future in K-12 education.”

To view the findings and learn more about this study, download Choose to Learn 2022 on the Tyton Partners website.

Editor’s note: The following is the text of a news release issued Monday by the Institute for Justice.

Editor’s note: The following is the text of a news release issued Monday by the Institute for Justice.

ARLINGTON, Va.—Today, the Institute for Justice (IJ) sent a letter to officials in Cobb County, Georgia, calling on them to stop weaponizing building and fire safety code laws to crack down on learning pods and other hybrid education setups.

During the pandemic, learning pods became a reliable way for parents to educate their children while traditional schools were closed. These pods are typically groups of children, organized by parents, who come together for instruction in a location such as a church or a home school setup to supplement either traditional schooling or home schooling.

The programs are so popular that the Georgia Legislature, with help from the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, passed a law in March of 2021 protecting these pods from overly burdensome regulations, including certain building codes and fire safety codes. Despite that, Cobb County’s fire marshal recently informed several different hybrid learning co-ops that if the buildings they were using did not reapply for a different certificate of occupancy by Aug. 8 they would be saddled with daily fines of $1,000.

“Cobb County’s proposed crackdown is a direct violation of the law protecting learning pods,” said IJ Attorney Suranjan Sen, one of the authors of the letter. “Officials should not be using building code laws to deny families the education they feel best fits their children’s needs.”

These pods are all currently using classroom space in different churches, and the churches each have certificates of occupancy for “assembly.” Yet the fire marshal is using a burdensome building code law to say these churches must also receive certificates of occupancy for “education” if they offer more than four hours of instruction per day. At the same time, the marshal is not demanding this of church preschool programs—further suggesting that the requirement is in fact unnecessary.

In order to reapply for the new permit, the churches would need to get an architect and submit site plans to the fire marshal, who would then inspect the buildings. After the inspection, the fire marshal could require the churches to make upgrades to their buildings that could total thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars. One pod, Arrows Academy, already shut down because of the crackdown last week.

“Learning pods provide families with flexible, quality education. Local governments should be making it easier for parents to find these educational options, not trying to regulate them out of existence,” said IJ Senior Attorney Erica Smith Ewing. “If these buildings are safe for mass and Sunday school, they’re also safe for learning pods.”

St. John the Baptist Hybrid School is another school that has come under threat by the fire marshal. The school, which serves 97 students, offers supplemental instruction for home schoolers Monday through Wednesday in Christ Episcopal Church in Kennesaw.

"St. John the Baptist Hybrid is an 'accredited with quality' educational program for Catholic home school families. We are a group of home school parents who came together with the primary goal of providing exceptional classes to supplement our home school experiences,” said Sharon Masinelli, the school’s administrator. “Our facility has passed all standards for a certificate of occupancy for assembly and was inspected by the fire marshal, who deemed this appropriate one year ago. Our hybrid program and facility have undergone rigorous evaluation by our accreditation agency. We sincerely hope the regulations which are newly imposed on facilities hosting home school groups will not deprive our families of school choice."

IJ is the nation’s leading advocate for educational choice. Earlier this year, IJ won a landmark 6-3 ruling before the U.S. Supreme Court which held that states may not prohibit families that participate in educational choice programs from selecting schools that provide religious instruction. Two years prior, IJ won another massive school choice case before the nation’s highest court.

At KaiPod Learning Centers, eight to 10 online learners or homeschoolers come together in person to work on their coursework and collaborate with their peers, supported by a highly-qualified KaiPod coach. Parents choose the curriculum that works best for their child delivered in a two-, three- or five-day plan.

Originally tagged “pandemic learning pods,” as though once the COVID-19 emergency had passed, so would these traditional education alternatives, the micro-school phenomenon appears ready to shed its born-of-the-moment modifier.

No longer regarded as the educational equivalent of mushrooms after a thunderstorm — ephemeral and generally undesirable — learning pods have rooted like oaks, with parents and students alike happily sheltering beneath their reliable canopies.

By spring 2021, a majority of parents (55%) and teachers (68%) who had started using learning pods were interested in continuing, according to a study by the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Among these likely here-to-stay enterprises is KaiPod Learning, a Boston-based startup founded by Amar Kumar, former chief product officer of Pearson Online Learning.

Designed to professionalize the learning pod/micro-school model typically cobbled together by parents, KaiPod centers provide safe, secure gathering places for small groups of students who pursue the online or homeschool curriculum of their choice under the guidance of a learning coach, usually a certified teacher.

“For years, families have been coming together to support their home schoolers and their online learners,” Kumar says. “We used to call these co-ops, or maybe sometimes, pods.”

Typically, parents, few of whom were trained instructors, provided oversight.

“What we are trying to do,” Kumar says, “is help create more structure around that segment.”

That the first KaiPod Learning center was spawned in Newton, Mass. — a half-hour ride from Fenway Park — in March 2021, while COVID-19 was still shuttering schools across America, is scarcely more than coincidence, Kumar says.

As Pearson’s CPO, he’d witnessed annual consumer turnover of more than 40% before COVID reshaped the landscape. The most common misgivings had nothing to do with academics; instead, parents decried the lack of friend-making opportunities, as well an absence of enrichment curricula — art, music, photography, design, and so on.

“The need existed before the pandemic,” Kumar says. “COVID just brought it to the forefront for everyone to be aware of what it means to be an online learner, to be a homeschooler.”

Does all this sound vaguely familiar? A gathering space for people who find their workaday experiences as keyboard-bound Jeremiah Johnsons isolating, monotonous, and otherwise unfulfilling? Hang on. Is KaiPod simply WeWork for students?

Ryan Holmes’ practiced wince indicates it’s not the first time he’s endured the analogy. As KaiPod’s chief academic officer, Holmes concedes it’s not an entirely inapt comparison. Both KaiPod and WeWork provide alternatives to unsatisfying go-it-alone screen stare-downs. But here’s where the comparison breaks down: WeWork presents the possibility of human interaction, team-building, and bonding; KaiPod actively cultivates it.

“We figure out what our kids are interested in, what they want to learn about, how they want to spend some of their free time,” Holmes says. “They want to play basketball, they want to learn a musical instrument, they want to work on crafts, then we'll … build [those] into our schedule.”

The multifaceted upside: “Kids can learn the new skill and through that process — it's socialized — they become friends and have a joyful experience.”

KaiPod’s approach is at least partly guided by the lessons emerging from loss of unstructured time in traditional school settings. When even recess comes with an agenda, Holmes laments, the school day is simply over-programmed.

“We intentionally built in an hour, at least, each day, for the kids to be kids,” he says. “We tell them, ‘Please don't be on your phone or computer. Go hang out with each other.’ ”

To facilitate the icebreaking, KaiPod centers are stocked with board games and multiplayer puzzles, facilitated by the onsite coach, who acts as sort of a cruise director.

KaiPod’s organizers also pride themselves in the program’s flexibility. While each center keeps regular business hours each weekday through the customary school year — generally 8 a.m.-3 p.m. — parents and students choose the schedule that suits them. Some attend all day, every day. Others select mornings three days a week, or even each Tuesday and Thursday afternoons.

The need for scheduling elasticity caught Kumar by surprise. He thought families would opt for five days a week, but he and his team were able to reshape their plans without disrupting their founding vision.

“There is a magic of kids coming together,” Kumar says. “There was actually a lot more energy there than I was expecting. … They instantly start to connect. … Now we hear kids say, ‘This is my tribe.’ ”

Here’s your analogy, then: KaiPod is the Golden Gate Bridge of education, a flexible span of learning opportunities suspended from the centers’ sturdy support structure. And, like any good suspension bridge, KaiPod’s blueprint is endlessly replicable.

Launched in Newton, Mass., KaiPod Learning Centers have expanded to Roswell Ga., (pictured) and Harrisburg, Pa.

Beyond Newton, KaiPod Learning centers are operating in Harrisburg, Pa., and Roswell, Ga. Scheduled to open in August are centers in New Hampshire (Manchester and Dover) and Arizona (Gilbert, Glendale, Scottsdale).

Attending KaiPod centers comes with a price tag, up to about $300 a week for a full-time, five-day schedule. Instructively, Arizona’s Legislature is considering an expansion of its empowerment scholarship accounts for all 1.1 million of the state’s K-12 students. New Hampshire’s Education Freedom Accounts plan allows eligible families earning up to 300% of the poverty line to steer some of their child’s state education funding to pay for private school tuition, tutoring, online learning programs, and other education-related expenses.

As the national mood for dollars funding students, rather than institutions, grows, Kumar is feeling optimistic, if not downright bullish, about the elasticity of KaiPod Learning’s future.

“I’d love in five years for us to have a national network of learning centers that are targeted to … helping these kids get the academic support, the enrichment, the socialization that they need,” Kumar says.

A network, he adds, that “helps more parents say, I can make this work for my kid.”

Service Learning Micro-school is a private K-12 school with a foundation firmly rooted in service to humanity, steered by goals such as the elimination of prejudice, economic justice, equality of men and women, balance of science and religion, individual investigation of the truth, oneness of humanity and unity in diversity.

CLEARWATER, Fla. – Before all the buzz about learning pods and micro-schools, some folks were already creating learning pods and micro-schools.

Jaime Manfra went down this path 10 years ago.

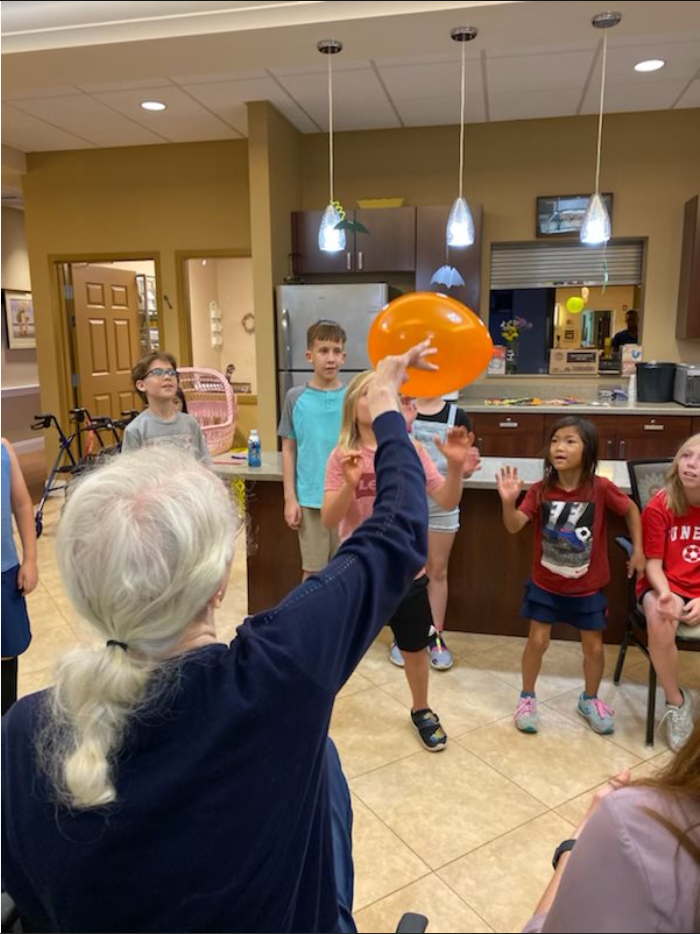

Her Service Learning Micro-school (SLS) is all about flexibility, diversity, community service. Students here spend a lot of time helping others, whether it’s making sandwiches for the homeless, volunteering at a horse rescue, or playing balloon volleyball with residents at the assisted living facility next door.

“Service is love in action, it’s virtue in action,” Manfra said. Students “need concrete ways of applying kindness.”

SLS isn’t for everybody. But with education choice, it shows what’s possible for everybody. Options that can be created and customized. For and by families and educators. To address whatever needs they feel are paramount.

To be sure, hurdles remain. SLS, for example, wrestled for years with finding a good facility. But policies to maximize flexibility for families and educators continue to get traction.

As they do, more problem-solvers like Manfra will find a way.

***

SLS began as a pod in 2012.

Manfra’s son Ajay turned out to be too much of a square peg for public school. So Manfra, who once taught classes in natural medicine, began homeschooling Ajay & a handful of other students.

Teacher-created activities demonstrate the inspiration a teacher feels, sparked by the students they work with. These adaptable lessons are balanced with the Edgenuity online school platform, which allows for measurable progress available to parents. Homework is optional and students are encouraged to spend after school hours with their families and friends, pursuing sports or other interests.

Word spread. The pod grew.

Now SLS has 44 students in K-12, most in middle & high.

All but two use school choice scholarships.

About 75 percent attended public schools. Many left because of peer pressure and bullying. Others left because of an academic environment their parents described as stifling.

At SLS, they found smaller classes, a competency-based approach, and far less pressure.

“I don’t see my children suffering anymore,” said Soji Jacobs, who enrolled her three children in SLS last fall. “They’re no longer ruled by grades, like it was decided who you were in life based on a grade,” continued Jacobs, a floral designer and former private school teacher. “They feel at home. They’re accepted for who they are. They’re genuinely loved.”

Barbara Warne enrolled her daughter Elizabeth into SLS six years ago, after six years at a highly touted magnet school. The school has a long waiting list, but for Elizabeth, who has ADHD, it never worked.

“I was brainwashed into thinking that this was the best school choice,” said Warne, a stay-at-home mom whose husband is an Army veteran and airplane mechanic. “Every day, they made her feel like a failure. It started to get to her mentally.”

Warne said she was sold on SLS as soon as she and Elizabeth attended an open house. She watched her daughter interact with Manfra and other students and immediately “start coming out of her shell.”

“It was unfolding in front of me,” Warne said. “I was getting my kid back.”

***

For Manfra, finding a good facility was the biggest hurdle.

Facilities are an issue for many on the education frontier. Official definitions of “school” can be a challenge for smaller, harder-to-define operations. There’s a hodge podge of zoning rules and building codes regulating “schools.”

Facility one for the pod that became SLS was in a house. But the pod outgrew it.

Facility two was in a community rec center. But it wasn’t ideal. School supplies and equipment had to be moved to and from the facility every day.

Facility three was another house. At this point, the pod had nine or 10 students. But the pod couldn’t stay because the house did not meet building codes for “educational occupancy.” Getting the pod up to code would have cost at least $50,000, Manfra said. And there was still the possibility local officials would not approve a zoning change and building use exemption.

Facility four was in a church. But if the pod wanted to become a private school – so it could accept school choice scholarships and be accessible to more families – the church would need upgrades.

Facility five was in another community rec center. It did meet requirements for a private school, so SLS could now accept scholarships. But when the center got a grant to renovate, it didn’t renew the lease.

Facility six is SLS’s current home. It’s a 4,600-square-foot commercial building that once housed a day care and construction company. Manfra had to be persistent to get a building use exemption, but in the end, SLS got what it needed.

***

SLS’s motto is “unity in diversity.”

Half the students are students of color. Nearly all are from working-class families.

A fifth are from military families.

Although the school encourages students to choose their battles, staff do not seek to prevent conflict or difference of opinion, seeing it as an opportunity for development, and assist with consultation when necessary.

They are Christian, Muslim, atheist, agnostic. Manfra & her two kids are Baha’i.

School choice enabled SLS to be diverse and different.

“Without the scholarships, only one type of family would be here,” Manfra said. “School choice scholarships make it so all families can be here.”

SLS occasionally holds “diversity BBQs” for its families.

Parents and students debate hot topics. Race. Religion. Politics.

The students “need to know that someone that doesn’t believe the same as you, or look the same as you, does not make them a bad person,” Warne said.

“I want my kids to hear all sides,” continued Warne, a registered Republican. People may disagree on some issues but “we’re trying to get somewhere, together.”

Things can heat up at the BBQs. But there is mutual respect and friendship.

The BBQs ends in hugs.

***

SLS is now seeking to help other micro-schools grow – and avoid the mistakes it made.

This year Manfra helped a former private school teacher in Tampa start her own micro-school. It’s a dual language school.

But there’s no end to the variety teachers can create, Manfra said.

“Give them their space, give them their freedom,” she said, “and they will show you what they can do.”

With education choice in the mix, the same is increasingly true for anybody with a good idea.

Manfra said if she can do it, anybody can.

“I’m not special,” she said. “There’s a lot of me’s.”

The MU Early Education STEAM Center, located on the campus of Marshall University in West Virginia, offers a “natural pod” learning environment to promote a child-initiated, teacher-supported curriculum in which children’s curiosities about the environment are supported.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Saturday on West Virginia’s herald-dispatch.com.

Gov. Jim Justice on Wednesday signed into law allowing “microschools” and “learning pods” of unlimited size to operate in West Virginia.

The new law, Senate Bill 268, says these would be sparsely regulated schools or groups of students that could combine concepts from homeschooling, private schooling and online schooling.

A learning pod is defined in the law as “a voluntary association of parents choosing to group the children together” for a prekindergarten-12th grade school as an alternative to other schooling.

A microschool is defined as “a school initiated by one or more teachers or an entity created to operate a school that charges tuition.”

Public dollars will be able to go toward these pods and microschools if the 2021 non-public school vouchers law survives a current legal challenge.

The voucher program, called the Hope Scholarship, provides families public money for every child they remove from pubic schools.

Families can then use this money on a nearly unlimited range of public school alternatives, including traditional private schooling, traditional homeschooling, online schooling and these pods or microschools.

To continue reading, click here.

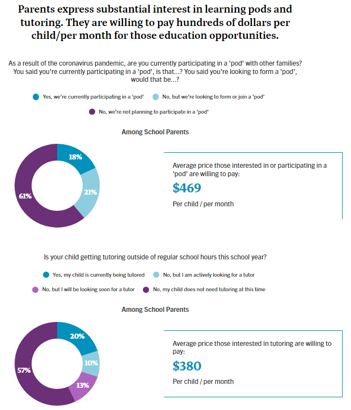

National School Choice Week The year 2022 arrived just after the second anniversary of the first American COVID-19 case being announced. A great deal has changed over the last two years, including a very large rise in multi-vendor education in the form of pods and tutors:

The year 2022 arrived just after the second anniversary of the first American COVID-19 case being announced. A great deal has changed over the last two years, including a very large rise in multi-vendor education in the form of pods and tutors:

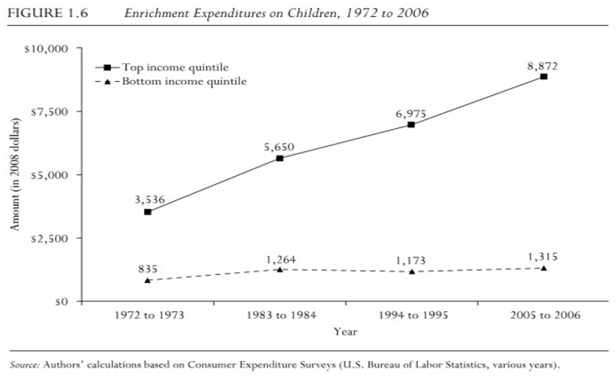

This is very significant and accelerated a pre-existing trend. For decades upper income Americans enrolled their children in custodial schools but spent more and more on enrichment outside of school.

This is very significant and accelerated a pre-existing trend. For decades upper income Americans enrolled their children in custodial schools but spent more and more on enrichment outside of school.

These families used custodial schools but they didn’t entirely rely upon them: their children got tutoring, participated in club sports, and a variety of extra things. When the pandemic struck families discovered they couldn’t necessarily rely upon the public education system at all, and families created supplemental pods in order to combat the deficiencies of impromptu digital learning.

These families used custodial schools but they didn’t entirely rely upon them: their children got tutoring, participated in club sports, and a variety of extra things. When the pandemic struck families discovered they couldn’t necessarily rely upon the public education system at all, and families created supplemental pods in order to combat the deficiencies of impromptu digital learning.

About 15% of parents switched schools during the first pandemic, about twice the normal rate, and matters continued to evolve from there. Home-schooling surged. Lawmakers, responding to constituent demand, passed a variety of new choice programs and expanded existing programs. Charter schools gained 240,000 students in the first year, while districts lost 1.45m.

Pods, both supplemental and full time, have joined the mix of options available to American families. While many decry the advent of pods citing equity concern, the issue is not that well-to-do families have access to them, but rather that low-income families have less access. Public policy changes will be needed to equalize access, but many American parents aren’t waiting on the glacial pace of state politics.

Stay tuned to this channel for further updates. The best is yet to come.

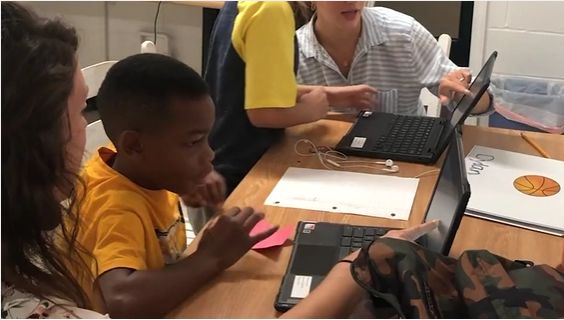

Students study in a pandemic learning pod organized by a group of South Carolina churches, business, nonprofits and individuals in underserved communities.

As the pandemic gripped the nation in the spring of 2020, American schools shut down and sent students home to finish the semester through online learning. The hastily organized programs were thought to be short-term solutions.

But as the rising numbers of coronavirus cases ended administrators’ hopes of fully reopening in the fall, Allan Sherer, a member of the pastoral staff at an Upstate South Carolina church, saw trouble ahead, especially for low-income minority students who had suffered academically in the spring.

The effort Sherer and his church made to educate low-income students over the course of the past two years received national recognition, placing as a semi-finalist for a $1 million STOP Award from Forbes Magazine and the Center for Education Reform.

Sherer’s North Hills Church, a non-denominational suburban congregation that draws 2,000 weekly worshipers, had sponsored academic summer camps for the past nine years. These camps focused on students in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods with the goal of preventing the annual summer learning slide. Now, with the pandemic sending students home permanently, Sherer feared these disadvantaged students in would suffer learning losses so steep that they would never recover.

“We heard numerous stories of children who, when sent home with Chromebooks, never even turned those Chromebooks on,” said Sherer, who has overseen local and global outreach for 15 years at the church in Greenville, S.C. The Palmetto State’s sixth-largest city, Greenville has a population of 70,720 and includes former textile mill villages that sit one county away from BMW’s first North American manufacturing plant, which has brought more than 11,000 jobs and contributed other economic development to the state. Still, intergenerational poverty remains an issue.

After seeing stories about how affluent families were banding together and hiring teachers to deliver in-person instruction to their kids, Sherer immediately thought, “Why shouldn’t children who do not have the means for pods like this also be served?”

Allan Sherer, pastor of missions and outreach at North Hills Church and leader of pods project

Sherer’s vision quickly led to the start of Come Out Stronger, an initiative to offer learning pods in the most underserved communities of the city. North Hills already had relationships with churches in those communities, including Black churches, community organizations and individuals committed to making a difference.

Less than six weeks later, the group raised more than $300,000, identified more than 40 staff members, and set up 10 Covid-compliant locations, each of which was able to serve as many as 24 public school virtual learners.

Sherer said the initiative succeeded because of two major factors: an unprecedented awareness of the intractable gap minority and low-income families face; and a unifying belief that those who have the least opportunity receive an excellent education. The fact that so many community members stepped up in a state that flew the Confederate battle flag on the statehouse grounds until 2015 is a testament to the efforts made toward racial progress in recent years.

“As a faith-based institution leading the way in this initiative we found no resistance or even hesitancy among businesses, public school administrators, predominantly white or African-American churches, and other community stakeholders to coalesce around doing whatever it takes to make sure children were not irreparably left behind,” Sherer said.

In Judson Mill community, which derives its name from the former textile plant there, 76% of children live in homes below the poverty line, placing it in the lowest .3% of comparable communities in the United States. Organizers identified it as a great place for a pod, and the community came together to help make it and other pods a reality.

A regional gas station chain provided financial support while also providing breakfast each day. The lead counselor in the community’s Title I school went door-to-door to persuade parents to place their children in the pod. A Black church offered its building and recruited volunteers of color to help. A white Presbyterian church supplied “a phenomenal reading specialist” who tested each student at the beginning of the school year, laid out personalized plans for reading development and then re-tested students at the end to gauge progress.

“Every child experienced significant reading improvement over the course of the year,” Sherer said.

Each pod was designed to serve 12 children at one time, with one group attending Monday and Wednesday and the other attending Tuesday and Thursday. Students arrived each day at 7:45 a.m. Trained staff helped children log into their school e-learning platform and stay on task with their work. The pods also provided tutoring, structure, snacks, and recreation. Most ended at 2 p.m. Each pod had a budget of $25,000.

The biggest challenge, Sherer said, was the uneven and inconsistent delivery of virtual learning.

For example, one first-grader was expected to log into four different learning platforms to complete her work. Each platform had its own log-in routine and its own method of completing and uploading work.

“This child lives with her grandmother, who cares for three other primary-age children,” Sherer said. “The challenge of navigating these platforms was immense.”

Sherer said establishing standard performance metrics also proved difficult.

“Because of the chaotic nature of the school year, with schedules shifting and children at times coming in and out of our pods it was not feasible to create an evidence-based measure of our success,” he said. “Anecdotally, we have dozens and dozens of stories of children who had never been successful in school who made the A-B honor roll.”

A few examples of that success can be found in the personal stories shared by staff on a video.

One student, described as a “quiet hoodie kid” who had nothing to say, came from a single-parent home and claimed affiliation with a local gang. His grades were all failing.

“We began to speak to him and love him and tell him who he could be,” said staff member Miriam Burgess. She said being around her son, who works in the pod, offered the student a positive male role model.

Within a couple of weeks, his “F’s” became “B’s” and “A’s” and he started talking.

“Now he runs through the pod like he owns it,” Burgess said. The boy’s mother told Burgess that he renounced his gang affiliation and “his whole demeanor is different.”

When another student joined one of the pods, he had been to class only four times since the beginning of the pandemic. He had forgotten how to read, did not know his math facts, and could not remember the order of the alphabet.

“He has gone from reading 35 words per minute to 102 words per minute,” said pod staffer Brittany Meilinger.

Then there were the three siblings who were in the custody of grandparents who also were raising a set of kindergarten twin siblings.

“Their grandmother had no hope of keeping up with all five children and their assignments,” pod staffer J.P. Camp said. “The pod has been life-changing for this family.”

Success stories like those earned the project a place on the list of 20 semi-finalists for the STOP Award. Sponsored by the Center for Education Reform and Forbes, it awarded a $1 million prize to an education provider, exceptional group of people, or organization that demonstrated accomplishment during the coronavirus pandemic by providing an education experience that was “Sustainable, Transformational, Outstanding, and Permissionless.”

Despite the success, Sherer’s pandemic pods ended when local schools reopened in August 2021. Although the pods were closed, church volunteers continued their work in education, logging more than 400 tutoring hours at local public schools so far this year.

Sherer said the experience offered valuable insights about the future of education and inspired the Greenville pod organizers to think even bigger.

The coalition is now working to open a network of private, hybrid, community-based schools that will serve the poorest regions of South Carolina.

“These smaller networks have the potential to drive a new era of innovation. We are re-imagining the entire in-person learning experience, and our partners are lining up,” Sherer said.

Space of Mind, A Modern Schoolhouse in Delray Beach based on the learning pod model, saw an uptick in the number of inquiries from families in the weeks leading up to the new school year.

Editor's note: reimaginED is proud to reintroduce to our readers our best content of 2021 such as this commentary from guest blogger Jonathan Butcher.

As students head back to school, we can check some predictions made last year about how COVID would change K-12 classrooms.

As students head back to school, we can check some predictions made last year about how COVID would change K-12 classrooms.

First, teacher unions forecast that schools would close in large numbers without additional federal spending. In June 2020, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten told Fox News, “We need the money for PPE [personal protective equipment],” and “We need the money for extra teachers; we need the money for extra cleaning and extra buses.”

Washington obliged. Since March 2020, the federal government has committed some $200 billion in COVID relief funds to K-12 schools.

Apparently, the schools didn’t need it. Or if they did, they had a funny way of showing it. According to research from Dan Lips at FREOPP, $180 billion of those funds remain unspent.

That’s a point worth emphasizing: Schools around the country opened this month, even in the midst of the uncertainties caused by the Delta variant, and they still have not spent most of the money teacher unions said would be required to get schools running again.

We can safely say this first prediction was wrong.

Second prediction: Public, private, and homeschool operations won’t return to normal anytime soon.

As Heritage Foundation research tracked last year, some of the largest districts in the U.S. saw significant enrollment declines in the 2020-21 school year. Arizona reported that 50,000 students “vanished” last fall, while Massachusetts saw a 4% enrollment decline statewide. New York City officials reported 3% fewer students, and enrollment declines also were documented in Montana, Wisconsin, Missouri, and North Carolina.

While schools were shut, parents created learning pods, and many state legislatures adopted proposals that gave parents and students more options in education. Combine those phenomena with surveys demonstrating that homeschooling is on the rise during the pandemic, it was easy to predict that 2021-2022 was not going to be like the prior school year.

The results of one recent study may be signs of things to come. Enrollment figures from 319 Indiana private schools show that 288 reported increases over the last three years. Nearly half (154) reported increases between the last school year and this one. In some instances, enrollment increases were phenomenal; 49 schools reported increases of at least 150%.

Indiana lawmakers expanded the state’s private school voucher program, which could account for some of the change, but reporter Anthony Kinnett cites parent dissatisfaction with mask policies and curriculum choices as two other reasons parents often gave in explaining their decisions to move to private schools.

A sifting of parents and students into different learning environments continues as the virus persists, and there are unmistakable signals that traditional public school enrollment is trending down. Contrary to the first forecast, this one appears to be coming true.

Finally, learning pods are here to stay, and some predicted this in 2020. Though state leaders in places like Pennsylvania and Maine tried to regulate the pods, parents have proved resilient.

At the beginning of this school year, with positive COVID tests still a concern for educators, parents and lawmakers are turning to pods again — but this time, participants have the benefit of experience.

In New Hampshire, state officials partnered with Prenda, a learning pod company based in Arizona, and are awarding grants to school districts to create learning pods. Two weeks ago, the New Hampshire Department of Education announced that four districts had been awarded grants to launch pods.

News reports from New Jersey and Florida say parents are forming pods again this year, while school officials in Arkansas say they are using small group sessions similar to learning pods in classrooms to start the year.

One new prediction for 2021-22: Parents will not wait to make choices about their child’s learning. Districts dithered over reopening plans last year, even as research demonstrated that schools were not COVID super-spreaders. Meanwhile, parents found solutions such as pods to meet their child’s needs.

Some state officials continue to respond to parent preferences by helping them access a different school if a child’s school closes or adopts a COVID policy (read: masks) that parents disagree with. Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey announced such a choice policy on Aug. 17.

It is safe to expect that parents will not wait — because they will not have to wait — for districts to decide if or when to reopen in the face of COVID this fall. They will just leave.