Hope, Caleb and Mary Hayes attend school on Florida's Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education at the Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, and Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, appeared Saturday on orlandosentinel.com. You can listen to reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s podcast with Emily Hayes here.

As a mother of five children, Emily Hayes knows that every child has different needs. And she is keenly aware that these needs change over time.

This means life at home must change as children grow and, so does life at school — or wherever a child is learning.

This is a lot for any parent to handle. Especially parents of children with special needs.

As a mom living in Port St. Lucie, though, Emily had access to K-12 education savings accounts — formerly known as Gardner Scholarships and now called Family Empowerment Scholarships for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA).

These flexible scholarship accounts allowed Emily to choose different education products and resources at the same time for her children, from textbooks to personal tutors and beyond.

The accounts “have the flexibility to change with the kid,” Emily says, which has allowed her and her husband to specifically meet each of their children’s needs with personal tutors and therapy services and in recent years, a private school. “Each of [my children] has so many different needs. And it changes year-to-year as they progress year to year,” she says.

Two of her children are on the autism spectrum; another has complications related to brain and spinal development.

Emily’s children are among the 25,000 Florida students using these accounts. Another 84,000 are using vouchers to attend K-12 private schools, and 80,000 more attend private schools using scholarships funded by charitable contributions to scholarship-granting organizations, such as Step Up for Students.

With the breadth and depth of Florida’s private education landscape, the state is ranked first in a new Heritage Foundation survey of all 50 states and Washington, D.C., in the areas of education choice, academic transparency, low regulations on schools, and a high return on investment for taxpayer spending on education. In three of the four categories examined Florida ranks among the top three nationwide.

For education choice, Florida ranks third behind Arizona and Indiana. All three states offer families numerous pathways to choose the learning environment that works best for their children. Studies find that education choice policies lead to higher levels of achievement and educational attainment as well as greater civic participation and tolerance, and lower levels of crime.

But for parents to choose well, they need information. That’s where the Sunshine State truly shines, earning first place for academic transparency. Earlier this year, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill that allows parents to see a list of materials that teachers are using in classrooms and view the catalogue of school library books. State officials also approved a proposal saying teachers and students must be free to engage in debates in class, but no one can be compelled to believe ideas, such as the idea that — because of their skin color — individuals deserve blame for past actions committed by others.

The high degree of transparency enables parents to hold schools accountable directly. Instead of trying to ensure quality through top-down regulations and red tape, Florida relies on bottom-up accountability, which is why it ranks second in the nation for regulatory freedom.

Schools and teachers have a high degree of freedom to operate as they see fit, within the boundaries set by age-appropriateness and civil rights laws, and parents provide accountability through their freedom to choose the schools that work best for their kids.

Florida lawmakers’ embrace of choice, transparency and regulatory freedom has produced one of the highest returns on investment in the nation, ranking seventh nationwide. While keeping spending within reason, Florida has steadily improved its performance on the National Assessment for Education Progress over the past two decades, rising to 17th nationwide in its combined fourth-grade and eighth-grade math and reading scores.

As for Emily, she says that “the kids are thriving.” The school aligns with her family’s values and has provided “targeted therapy” for each child — a winning combination.

But it took more than a single assigned school to help her and her children find success.

“Not every school is going to meet the needs of every kid,” Emily says, which makes education choice essential.

If an assigned school anywhere in the country is not meeting a child’s needs, parents should point to Florida and ask their lawmakers, “Why can’t we have more options, too?”

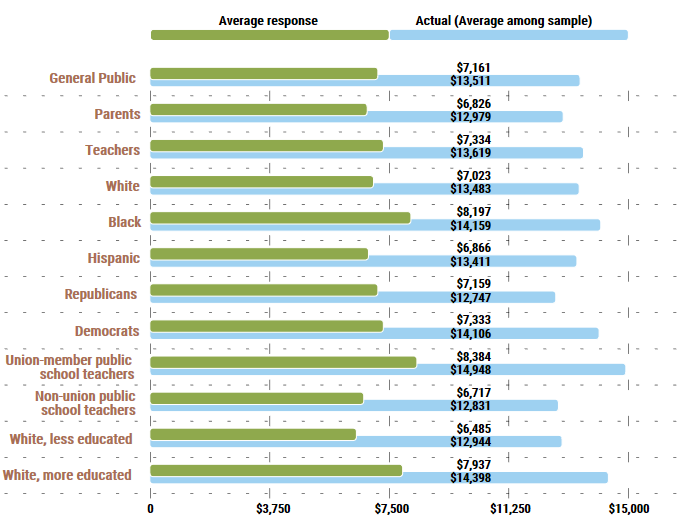

A recent Education Next poll found the general public, parents, teachers, Republicans and Democrats underestimate per-student spending by approximately $6,000.

In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, Viola asks to see the face of Olivia, a grieving countess who wears a veil.

“Is’t not well done?” asks Olivia. “Excellently done, if God did all,” Viola replies, slyly suggesting Olivia’s good looks would be impressive if they were natural and not due to the generous application of makeup.

Last week in the Washington Post, the University of Virginia’s Robert C. Pianta got his facts wrong, and he could not add enough color to the supposed benefits of socioemotional learning or the shortcomings of No Child Left Behind to obscure this simple truth: K-12 spending has not decreased over time.

And whether due to pressure exerted through social media (more on that below) or otherwise, the Post issued a correction to the spending claims this week. But Pianta’s position that increased spending should drive policy choices still drives his column and weakens some of his otherwise sensible proposals.

Pianta’s argument begins naturally enough. He points to the same examples of low test scores and uninspiring examples of student performance on the Nation’s Report Card and international tests that are cited by nearly every commentator on K-12 district schools in the U.S. (“ever-growing achievement gap,” “public schools in a state of crisis,” etc.).

Then come the cosmetics, poorly applied.

“This issue has been recognized for decades,” he says, but “politicians neglected to consider the thing that might improve education the most but never emerged as part of a far-reaching solution set: investing more public money in our teachers and children.”

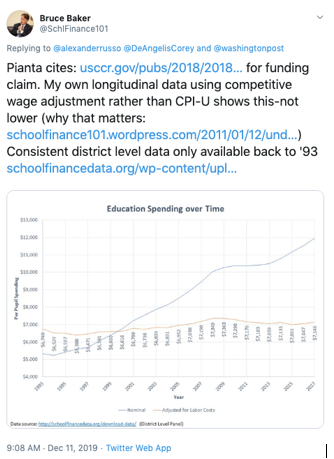

“The biggest problem plaguing U.S. public schools,” he says, is “a lack of resources.” Funding has decreased since the late 1980s, Pianta said in the original column and cited a study by Rutgers Professor Bruce D. Baker—who proceeded to refute Pianta’s contention via twitter:

Baker’s comment is notable because he has argued that spending does matter in order to improve student outcomes, but even he took issue with this part of Pianta’s analysis.

In fact, Baker’s figures are too tame. After adjusting for inflation, K-12 spending per student has nearly doubled since 1980 and is nearly four times greater than 1960. Spending has increased in every category, from administration to instruction to plant operations. The financial crisis more than a decade ago temporarily stalled annual increases, but the downturn did not erase years of increases, and spending graphs are pointing up again (in May, the U.S. Census announced “U.S. Spending Per Pupil Increased for Fifth Consecutive Year”).

Even with the Post’s correction, Pianta’s column still says schools “have been starved for funds.”

Still, Pianta is not alone in his error. A nationally representative poll finds the general public, parents, teachers, Republicans, and Democrats underestimate per student spending by approximately $6,000. Borrowing from the Bard again: In Pianta’s hit, he misses. Once actual spending numbers are provided, fewer survey respondents say that we need more money in education.

Despite his creative accounting, Pianta closes with a welcome call for teacher unions “to become more responsive toward performance evaluations.” If policymakers want to increase teacher pay and benefits—which make up some 80 percent of school budgets—then taxpayers and parents should have better ways to measure teacher effectiveness. Across-the-board pay raises, as awarded recently in San Diego and in states where teachers went on strike earlier this year and last, are sloppy ideas that reward poorly-performing teachers as much as effective teachers. District officials should treat educators like professionals and compensate them accordingly.

And we should put this debate to rest. Pianta’s inaccurate claims of K-12 spending cuts cannot support his sensible plea for compromise over teacher evaluations and some of his other ideas, such as “inspiring talented people to enter the teacher workforce.”

The countess Olivia assures Viola that her good looks are natural and says, “’Tis in grain, sir, ‘twill endure wind and weather.” Pianta’s claims that K-12 spending has decreased were clearly less robust. Spending has increased over time, and the ways in which school leaders and lawmakers use these resources still matters more for student success than how much is spent.