Editor’s note: This post is another in our fact-checking series, one that focuses solely within the arena of educational choice. The goal of fact-checkED is to bring clinical precision to complex issues that are easily misunderstood, aiming to counteract incorrect information before it continues to circulate.

![]() An Oct. 30 news story in the Gainesville Sun about the Family Empowerment Scholarship (FES) included an uncontested assertion by the Florida Education Association that the new program will drain money from public schools:

An Oct. 30 news story in the Gainesville Sun about the Family Empowerment Scholarship (FES) included an uncontested assertion by the Florida Education Association that the new program will drain money from public schools:

Researchers from the state’s teachers union say according to their calculations with those averages, the program will pull $1.2 million to 1.3 million from the Alachua County School District and $2.2 million to 2.4 million from Marion County Public Schools.

“It’s a hit to public schools,” said Eileen Roy, Alachua County school board member. “Parents need to know that it’s $1 million less to help their children. This is a very scary move, and we can’t afford to ignore it.”

The article continues:

Shortly after the program passed, the Florida Education Association projected that the scholarships would divert $11 million from Alachua County Public Schools over the next five years. For Marion County, they predicted a $19 million loss.

This is false.

It’s appropriate that this claim was published around Halloween, because it perpetuates what amounts to a ghost story aimed at frightening people.

Leave aside the school board member’s us-versus-them statement that “parents need to know that it’s $1 million less to help their children” – which completely ignores the low-income parents in her county who see the new scholarship as a way to help their children find the right education environment. Do they not count in her social order?

Instead, let’s focus on the math.

Florida has 18 years of financial data from the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship (FTC), on which the new scholarship is modeled. Eight different independent fiscal impact studies have concluded the FTC saves taxpayer money that can be re-invested in public schools. Not a single study has shown otherwise. That’s because the value of the scholarship is less than what taxpayers spend per student in district schools.

A Florida Tax Watch report on the “true cost” of public education, released in March, determined the FTC scholarship in 2017-18 was worth 59 percent of all categories of per-pupil spending for district schools, which Tax Watch calculated to be $10,856.

The new FES vouchers, like the current FTC scholarships, average between $6,775 and $7,250.

Florida will spend about $130 million this academic year to award Family Empowerment Scholarships to 18,000 students. If you add the basic per-pupil funding increases over the last two years to update the Florida Tax Watch calculation from 2017-18, it would cost the state about $200 million to educate the same students in district schools.

It’s worth noting that the Florida Education Association was the lead plaintiff in a years-long lawsuit that sought to kill the FTC scholarship. The Florida Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the suit in 2017, after a lower court found the plaintiffs couldn’t provide any evidence that the program harmed public schools. That included an “analysis” similar to the one the union has trotted out against the FES.

Finally, the state doesn’t pay school districts for empty seats in classrooms, regardless of why students left. If they move to another district, or out of state; if their parents decide to home-school them; or if they leave to attend a private school and their families pay tuition out of their own pockets, the impact on the districts in per-pupil funding is the same.

Oddly, it only seems to become an existential threat to public education when a low-income student takes advantage of a scholarship or voucher to attend the school of his or her choice.

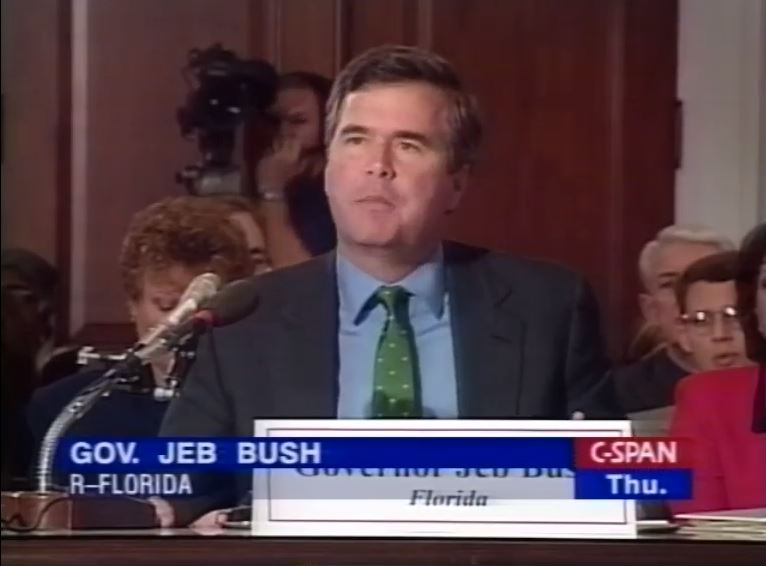

Florida's then-Gov. Jeb Bush testifying before a U.S. House committee Sept. 23, 1999.

Florida's then-Gov. Jeb Bush testifying before a U.S. House committee Sept. 23, 1999.

Twenty years ago this week, Gov. Jeb Bush spoke before the House Education Budget Committee about Florida’s recently passed A+ Plan and the state’s first voucher, the Opportunity Scholarship Program.

“It’s been fun, in all honesty,” Bush said with a smirk, “to watch the myths that have been built up over time when you empower parents.”

Those myths were shattered, Bush said, though he admitted the program was only just a few months old at that point. Nevertheless, two decades of evidence have proved him correct.

By the time of Bush’s presentation, the Opportunity Scholarship had awarded scholarships to 134 students at two schools in Pensacola. Seventy-six of those students used the program to attend another higher-performing public school, while 58 used the voucher to attend a private school, according to Bush’s testimony.

The first myth Bush called “the brain drain,” which occurs when only the high-achieving kids leave public schools. But according to Bush, the students on the program were no more or less academically advantaged than their peers who remained behind.

The second myth was that vouchers would only benefit higher-income students. “Eighty-five percent of the students are minority,” Bush said. “Eighty-five percent qualify for reduced and free lunch. This is not a welfare program for the rich, but an empowerment program for the disadvantaged.”

The third and final myth he called “the abandonment myth” -- schools where students leave will spiral ever downward.

Twenty years later these myths remain busted.

Eleven years of research on the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship show the critics’ claims ring hollow.

• Students attending private schools with the help of the scholarship are among the lowest-performing students in the public schools they leave behind.

• Today, 75 percent of scholarship students are non-white, 57 percent live in single-parent households, and the average student lives in a household earning around $27,000 a year. Researchers at the Learning Systems Institute at Florida State noted that these students are also more economically disadvantaged than their eligible public-school peers.

• More importantly, scholarship students are achieving Jeb Bush’s goal of gaining a year’s worth of learning in a year’s time.

• Even the abandonment myth remains untrue. Overall, public schools with large populations of potentially eligible scholarship students actually performed better, as a result of competition from the scholarship program, according to researchers David Figlio and Cassandra Hart.

When Jeb Bush took office just 52 percent of Florida’s students graduated. Today 86 percent of students graduate. According to the Urban Institute, students on the scholarship are more likely to graduate high school and attend and later graduate from college. State test scores on the Nation’s Report Card are up considerably since 1998 too. And when adjusting for demographics, Florida, which is a majority-minority state, ranks highly on K-12 education compared to wealthier and whiter peers.

There’s still room for improvement. But the naysayers at the turn of the century have been proven wrong.

Florida's First District Court of Appeal

This is the second of two posts on the judicial history of Florida's Blaine Amendment with regard to public aid to private religious institutions. Part one can be read here. The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to weigh in on the constitutionality of state Blaine Amendments in 2020.

Lawyers defending Florida’s first school voucher program in Bush v. Holmes demonstrated the state historically allowed public funding to flow to many religious organizations providing public services, including through the McKay Scholarship for children with special needs. The First District Court of Appeal refused to acknowledge these programs.

Supporters of the Opportunity Scholarship program also cited several Florida Supreme Court cases which upheld aid to religious institutions as constitutional. But the appellate court found a way to ignore this precedent too.

Koerner v. Borck (1958) dealt with the last will and testament of Mrs. Lina Downey, who had donated a parcel of land to Orange County for use as a county park, but with the provision that Downey Memorial Church be granted a perpetual easement to access the lake for the privilege of baptizing members and swimming.

The court upheld the will, concluding,

“to hold that the Amendment is an absolute prohibition against such use of public waters would, in effect, prohibit many religious groups from carrying out the tenets of their faith; and, as stated in Everson v. Board of Education, supra, 67 S. Ct. 504, 505, "State power is no more to be used so as to handicap religions, than it is to favor them."

In 1959 the Florida Supreme Court heard Southside Estates Baptist Church v Board of Trustees, a case in which the court ruled religious institutions could use public buildings (in this case a public school) for religious meetings.

The court was not persuaded that minimal costs associated with the “wear and tear” of the building constituted aid from the public treasury, and concluded there was “no evidence here that one sect or denomination is being given a preference over any other.”

In Johnson v. Presbyterian Homes of Synod of Florida, Inc. (1970), tax collectors for Bradenton and Manatee County challenged a law that gave property tax exemptions to non-profits operating homes for the elderly after a religious organization applied. Presbyterian Homes of Synod, a religious non-profit operating homes for the elderly, maintained a religious atmosphere, offered religious services and employed an ordained Presbyterian minister who conducted services every day except Sunday. Most residents were even practicing Presbyterians.

The Florida Supreme Court determined the tax exemption benefit was available to all, not just Presbyterians, and ruled:

“A state cannot pass a law to aid one religion or all religions, but state action to promote the general welfare of society, apart from any religious considerations, is valid, even though religious interests may be indirectly benefited.”

Nohrr v. Brevard County Education Facilities Authority (1971) dealt with the issue of government issue bonds potentially being received by religious schools. The Florida Supreme Court found no problem here either.

In all four cases the Florida Supreme Court held the law did not violate the constitutional prohibition on direct or indirect aid to religious institutions. In all instances, the court examined who benefited from the aid, and required that the aid benefit the general public and/or required that no religious group be favored over the other.

The appellate court majority brushed aside these arguments, noting that the Opportunity Scholarship was different because the financial aid came directly from the state treasury, making the scholarship “distinguishable from the type of state aid found constitutional.” In fact, it appears the appellate court restricted Florida’s “no aid” provision to “payment of public monies,” though it failed to consider other similar programs such as McKay.

Having crafted itself exemptions to prior state Supreme Court precedent, the appellate court cited cases in Washington (2002), South Carolina (1971) and Virginia (1955) where state supreme courts held that direct subsidies to students were, in effect, benefits to religious schools.

This directly contradicted the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), which determined the benefit to religious institutions from school vouchers were merely “incidental.”

The Florida Supreme Court had even weighed in on whether these benefits were direct or incidental during a 1983 case, City of Boca Raton v. Gilden, which upheld the city’s subsidy to a religiously affiliated daycare provider. The court declared:

“The beneficiaries of the city's contribution are the disadvantaged children. Any ’benefit‘ received by the charitable organization itself is insignificant and cannot support a reasonable argument that this is the quality or quantity of benefit intended to be proscribed.”

The appellate court in Bush v. Holmes failed to understand that the constitutional question hinged not on the method of aid, but who was the intended beneficiary of the aid. Though Florida’s constitutional language may appear clear, its longstanding history of neutrality in funding medical and educational services at secular and religious institutions, has muddied the waters.

Despite being told her son, Brandon, would never learn to read, Donna Berman persisted in her quest to find an appropriate education setting for him where he could thrive. Brandon died Sept. 10, 2017, at the age of 19.

Editor’s note: The Orlando Sentinel recently published commentary arguing that private schools that accept vouchers discriminate against children with special needs. A Volusia County parent of a special needs child begs to differ. Donna Berman's son, Brandon, who had autism and a brain tumor as well as muscular dystrophy and seizures, was denied admission to a local public school. Berman tells Brandon's story in a response to the Sentinel, published Thursday, noting that until Brandon received a Gardiner Scholarship to attend a private school, he was "a space-age kid stuck in a stone-age system."

Special education is a complex topic, dealing with dozens of laws, hundreds of unique needs and thousands of children across the state. It’s a topic that deserves better and deeper discussion than recently presented.

A recent column by Scott Maxwell (“Voucher schools can reject kids with disabilities,” Aug. 7) argued that private schools can discriminate against children with disabilities. However, individual public schools can also reject students with disabilities. I know this from personal experience. Worse still, the column was published while Volusia County public schools are under investigation by the Justice Department for discriminating against students with autism.

Read more here.

To read more about Brandon, click here.

In a historic expansion of school choice in Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis signs into law May 9 a bill creating the Family Empowerment Scholarship, a new, state-funded voucher program.

Editor’s note: The Gainesville Sun editorial board, in an opinion posted July 28, called for greater oversight for private schools that will receive about $130 million this year from the state budget for a new voucher program. The editorial alleges these private schools lack accountability to ensure academic quality, a highly-trained teacher force and policies that prevent discrimination against students. Executive director of Florida Voices For Choices Catherine Durkin Robinson responded in a column the Sun published Tuesday, arguing that school accountability should be a balance between regulations and family choice.

In a recent editorial, The Sun equated regulation of education with quality academic outcomes. It ignores the fact that parental choice is an effective form of accountability — and a vital tool to equalizing opportunity.

For too long, district schools had a monopoly on teaching most of the students within their jurisdiction, and parents had no choice but to send their children to whatever school that district assigned. Since parents had no options, the theory went, schools needed tight regulatory and accountability standards. That’s the only way we’d know how they were working.

Those standards showed us that for millions of low-income, minority children, that system was not working.

School accountability should be a balance between regulations and family choice. And the evidence suggests Florida’s tax scholarship program has found a good balance. Even with far less funding, the lower-income students using the scholarships are generating better academic results.

To read more, click here.

Students and parents advocate for school choice scholarships in a 2015 advocacy event in Tallahassee.

As students begin returning to classrooms, I can’t help but notice that some parents are willing to risk it all for their child’s education.

Many are not satisfied with their current learning environment and have taken extreme measures for a chance to have an equal opportunity. Reports across the United States reveal that parents lie, cheat, and find loopholes to beat the system because they want their children to have a better chance than they did.

![]() Recently, the Chicago Tribune reported that some parents are willing to give up their guardianship in order for their college-bound child to qualify for financial aid. A loophole in the system prevented some qualifying low-income families from not receiving their due funding.

Recently, the Chicago Tribune reported that some parents are willing to give up their guardianship in order for their college-bound child to qualify for financial aid. A loophole in the system prevented some qualifying low-income families from not receiving their due funding.

A few years back, an Ohio mother lied about her address so her daughters could attend better district schools – and ended up in jail. Another mother, homeless and unemployed in Connecticut, was arrested for enrolling her 5-year-old son at an elementary school he wasn’t zoned to attend.

These parents’ actions highlight that policymakers aren’t doing enough to help public education fulfill the promise of equal opportunity.

The fight is not over. And Florida Voices for Choices will help them fight for their children.

Although all children from various socioeconomic backgrounds deserve a quality education, that education will look different for each family – because no one size fits all.

Some families can afford to move into neighborhoods that have A-rated district schools. Other families may opt to send their kids to charter or magnet schools if they are lucky enough to get accepted.

But many families don’t have the means to send their kids where they want. They may have an opportunity to receive a scholarship or voucher, but countless do not. These parents must fight to send their kid to a learning environment that works best for them.

In Florida, the fight continues to end scholarship waiting lists. Step Up For Students, the state’s largest scholarship funding organization, still has a growing waitlist for the Gardiner Scholarship, a program serving nearly 14,000 children with special needs.

More than 20,000 families applied for the scholarship this year, but there is not enough money allocated for the program in the state budget to fulfill demand.

Those parents need certain therapies for their kids, and many traditional schools don’t offer that. A scholarship could help them cover the cost. For years, they shared with lawmakers their desire to see an increase in funding.

Their fight is not over.

Nearly 18,000 other families will be getting off a waitlist this school year to receive the Family Empowerment Scholarship, a program that serves low- and middle-income families that might not have been able to afford tuition at private schools.

One of those parents is Mikekisha Turner, a single mom with three children who struggles to make ends meet in Miami. In Mikekisha’s neighborhood, many things aren’t accessible to all. She wants her children to be in a school with happy teachers. Without a good education, she knows her children will struggle in life. That’s why she believes equal opportunity means having the power of choice.

Mikekisha’s fight is not over.

That’s why training parents to advocate for policies that matters to them makes a difference. Advocate parents are more informed about options available to them and may not have to resort to extreme measures like criminal behavior in order to help their kids.

At Step Up For Students, my team’s role is anchored in grassroots mobilization. Florida Voices For Choices strives to expand the coalition of faith leaders, parents, and other advocates in support of school choice. We educate all advocates on policies, laws and threats that directly impact the scholarship programs. We train advocates to testify before legislative committee hearings, write letters to editors in their local newspapers, and participate in educational campaigns. We work together to help all children have a chance to succeed in varying educational environments.

Why?

Because we know the fight is not over.

SEBRING, Fla. – When it comes to public education, Andy Tuck, the new chair of the Florida Board of Education, is an all-of-the-above kind of guy. His wife is a district schoolteacher. His children attended district schools. They had the option of enrolling in an International Baccalaureate program he approved as a district school board member.

SEBRING, Fla. – When it comes to public education, Andy Tuck, the new chair of the Florida Board of Education, is an all-of-the-above kind of guy. His wife is a district schoolteacher. His children attended district schools. They had the option of enrolling in an International Baccalaureate program he approved as a district school board member.

But Tuck doesn’t think it makes sense to limit educational choice to district options. Charters. Vouchers. Education savings accounts. Giving more parents more access to all of them, he said, is “critical.”

“I felt like my children got a first-class education at Sebring High School … Our choice was to leave our children in the traditional public school. But don’t think for minute I wouldn’t have had a different choice had I needed to,” Tuck, 49, said in a podcast interview with redefinED. “We need to continue to expand options. I don’t think that’s something we ever need to stop.”

Tuck is an orange grower in Highlands County, where the biggest city has 10,000 people and the school district and Walmart are among the biggest employers. He grew up a free-and-reduced-price lunch kid. He was the first in his family to earn a college degree.

He’s got a good story about why he became engaged in education issues. He’s got another about why he became a fan of school choice. We could tell you, but sitting in Cowpoke’s Watering Hole on U.S. 27, Tuck tells it better himself.

Tuck doesn’t fit neatly into anybody’s box. He views educational choice as nonpartisan. He thinks rural areas could use more of it (despite the prevailing narrative that choice won’t work there). And while it’s unclear where Florida is headed on boosting teacher pay (intriguing hints here), he’s all for finding ways to do that now.

“We have a world-class education system here, and we’re going to need to show that in our compensation,” Tuck said.

Enjoy the podcast.

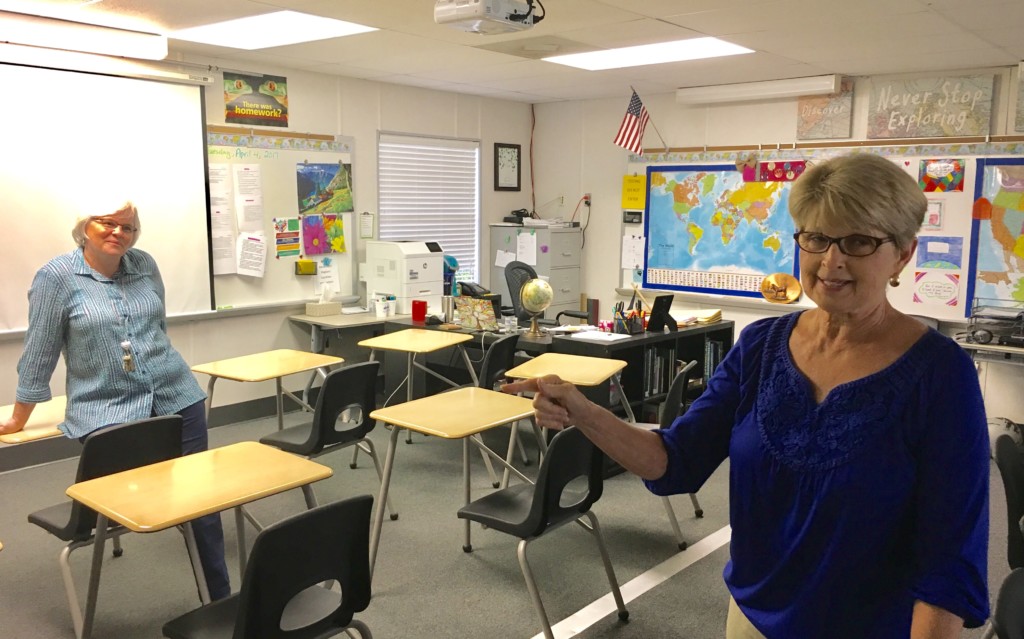

School choice can't work in rural areas? Tell that to Judy Welborn (above right) and Michele Winningham, co-founders of a private school in Williston, Fla., that is thriving thanks to school choice scholarships. Students at Williston Central Christian Academy also take online classes through Florida Virtual School and dual enrollment classes at a community college satellite campus.

Editor’s note: Throughout July, redefinED is revisiting stories that shine a light on extraordinary schools. Today’s spotlight, first published in April 2017, demonstrates that education choice can thrive in rural counties, where parents and educators are every bit as devoted to students as those in urban areas.

Levy County is a sprawl of pine and swamp on Florida’s Gulf Coast, 20 miles from Gainesville and 100 from Orlando. It’s bigger than Rhode Island. If it were a state, it and its 40,000 residents would rank No. 40 in population density, tied with Utah.

Visitors are likely to see more logging trucks than Subaru Foresters, and more swallow-tailed kites than stray cats. If they want local flavor, there’s the watermelon festival in Chiefland (pop. 2,245). If they like clams with their linguine, they can thank Cedar Key (pop. 702).

And if they want to find out if there’s a place for school choice way out in the country, they can chat with Ms. Judy and Ms. Michele in Williston (Levy County’s largest city; pop. 2,768).

In 2010, Judith Welborn and Michele Winningham left long careers in public schools to start Williston Central Christian Academy. They were tired of state mandates. They wanted a faith-based atmosphere for learning. Florida’s school choice programs gave them the power to do their own thing – and parents the power to choose it or not.

Williston Central began with 39 students in grades K-6. It now has 85 in K-11. Thirty-one use tax credit scholarships for low-income students. Seventeen use McKay Scholarships for students with disabilities.

“There’s a need for school choice in every community,” said Welborn, who taught in public schools for 39 years, 13 as a principal. “The parents wanted this.”

The little school in the yellow-brick church rebuts a burgeoning narrative – that rural America won’t benefit from, and could even be hurt by, an expansion of private school choice. The two Republican senators who voted against the confirmation of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos – Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine – represent rural states. Their opposition propelled skeptical stories like this, this and this; columns like this; and reports like this. One headline warned: “For rural America, school choice could spell doom.”

A common thread is the notion that school choice can’t succeed in flyover country because there aren’t enough options. But there are thousands of private schools in rural America – and they may offer more promise in expanding choice than other options. A new study from the Brookings Institution finds 92 percent of American families live within 10 miles of a private elementary school, including 69 percent of families in rural areas. That’s more potential options for those families, the report found, than they’d get from expanded access to existing district and charter schools.

In Florida, 30 rural counties (by this definition) host 119 private schools, including 80 that enroll students with tax credit scholarships. (The scholarship is administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog.) There are scores of others in remote corners of Florida counties that are considered urban, but have huge swaths of hinterland. First Baptist Christian School in the tomato town of Ruskin, for example, is closer to the phosphate pits of Fort Lonesome than the skyscrapers of Tampa. But all of it’s in Hillsborough County (pop. 1.2 million).

The no-options argument also ignores what’s increasingly possible in a choice-rich state like Florida: choice programs leading to more options.

Before they went solo, Welborn and Winningham put fliers in churches, spread the word on Facebook and met with parents. They wanted to know if parental demand was really there – and it was.

But “one of their top questions was, ‘Are you going to have a scholarship?’ “ Welborn said.

Cathy Lawrence, a stay-at-home mom, said her daughter Destiny needed options because of an age-old problem: Bullying that got so bad in middle school, Destiny’s academics began to suffer. Lawrence and her husband, a welder, couldn’t afford private school on their own. But using tax credit scholarships, they enrolled Destiny and her brother in the new Williston school, where they remain four years later.

“The scholarship gives them the advantage, now, to excel academically – to be in a proper environment, and not be subject to all that stuff in a crazy world,” Lawrence said.

Williston Central embodies educational choice beyond scholarships. More than 30 students take online classes through Florida Virtual School. A half dozen take dual enrollment courses at a community college satellite campus. Innovative choice initiatives like course access and education savings accounts could supplement such programs, and be especially useful for rural students.

The school has proved its resourcefulness in more traditional ways. It secured hand-me-down desks from a public school that was moving into new digs, and its parents sanded and painted them anew. The school also raises about $170,000 a year beyond tuition, Welborn said, to ensure the quality its parents demand.

Many of those parents are the backbone of Levy County’s working class: farmers and firefighters, nurses and deputies, hair stylists and day care workers. Public school educators are in the mix. So are private-pay parents, including a doctor, a banker and an accountant. Most of them attended local public schools. But there’s a shared belief among them that when it comes to raising children, there needs to be a consistent message – a “united front,” Winningham said – from parents, teachers and pastors.

That doesn’t mean academics take a back seat. The school is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools and the Florida League of Christian Schools. Its teachers are certified and have at least bachelor’s degrees. Most have deep roots in Levy. “We’re very selective about our teachers,” said Winningham, from nearby Archer (pop. 1,118). “We wanted teachers who would go beyond teaching, who would connect with families.”

Lawrence said the parents go above and beyond, too, because they know they have a good thing with the school and the scholarships. “If you want to see how many of us would be up in arms,” she said, “try taking it away.”

![]() Editor’s note: One of the most pervasive of all education choice myths is the one that claims schools that accept scholarships are not held accountable to the public for their success -- or failure. We looked at the "no accountability” myth last week but take a deeper dive in today's post. You can see more myth busting here, or by clicking the link at the top right-hand corner of this page.

Editor’s note: One of the most pervasive of all education choice myths is the one that claims schools that accept scholarships are not held accountable to the public for their success -- or failure. We looked at the "no accountability” myth last week but take a deeper dive in today's post. You can see more myth busting here, or by clicking the link at the top right-hand corner of this page.

Many cultures around the world have a common trope: a mythical creature parents invoke to scare their children into behaving. It goes by different names – the bogeyman, Baba Yaga, El Coco – but the admonition is usually the same: “If you don’t do as I say, so-and-so is going to get you!”

Critics of education choice deploy their own bugbears to frighten the masses.

For years these critics have argued that voucher programs divert tax dollars from public schools to “unaccountable” private schools. That’s been a popular talking point for opponents of Florida’s new Family Empowerment Scholarship:

“There are no systems in place for accountability.” “A wild west of unregulated, unaccountable voucher schools.” "Tens of millions of public dollars each year for primarily religious private schools that have no public accountability."

(This is on top of other terrifying rhetoric such as, "The way Florida sells 'choice' relies heavily on gaslighting its citizens.")

Cue the spooky organ music.

In reality, voucher schools are subject to two forms of accountability: the top-down regulatory model, albeit with a lighter touch than what public schools receive; and the kind you get from the bottom-up through parental choice, something few public schools face.

The debate shouldn’t be whether voucher schools should be regulated and held accountable (they are). Rather, it should be about finding the right mixture of different methods.

Public schools face large degrees of government regulatory accountability, from standardized testing, to curriculum, to teacher certification, to restrictions on how they can spend funds, and on and on. Private schools aren’t “unregulated,” as many critics claim. Florida law, for example, includes nearly 12,000 words of regulations governing schools that participate in the state’s tax credit scholarship program.

Those schools must provide parents information about teacher qualifications; test students in grades 3-10 in reading and math on state-approved national norm-referenced tests; and conduct annual financial reports if the school receives more than $250,000 from any scholarship source, to name just a few. Schools are also subjected to health, safety, fire and building occupancy inspections. Starting in 2019-20, new participating schools must be inspected by the Florida Department of Education before accepting any scholarship students.

Regulations that are burdensome can deter private school participation in voucher programs, which limits choices (and the quality of those choices). Making private schools subject to the same regulations as public schools would defeat the purpose of choice, which is to eliminate sameness and encourage diversity and innovation, allowing parents to customize their children’s education.

There’s a compelling argument that district schools are overregulated, often made by the stakeholders themselves. Teachers and parents complain about too much testing, too much paperwork, too much programmed instruction. “Just let me teach!” is the cri de coeur of many educators.

Like private and charter schools, public schools should be allowed more flexibility to operate, so they can better meet the needs of their students. It’s not about favoring one system over another. It’s about choosing students over systems, and allowing their families to seek the best options.

Putting that choice in the hands of parents represents the most direct and effective form of accountability. Their decision to attend or not attend a school serves as the ultimate oversight. If a school fails to deliver, it loses students and resources as dissatisfied parents look elsewhere.

This form of accountability is in short supply in public schools, particularly in low-income areas, where parents generally can’t afford to move to a neighborhood with a better school or pay tuition for a private school. They are stuck attending the school they are zoned for, regardless of whether it is working for their child.

These district schools are supposed to be accountable to their government overseers, but the consequences can’t match the immediacy of a parent’s decision to act now. How many public schools are closed for non-performance? How long does the process take? When public schools are deemed to have performed poorly, the response often is to advocate spending more money on them, in the misguided correlation between inputs (dollars) and outputs. What kind of accountability is that?

Letting parents decide has demonstrable benefits. For 10 consecutive years, Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students – who are among the most economically disadvantaged and lowest- performing students in the public schools they leave behind – have achieved the same solid test score gains in reading and math as students of all income levels nationally. In addition, an Urban Institute study released earlier this year found that students using the scholarship are up to 43 percent more likely to enroll in four-year colleges than their peers in public schools, and up to 20 percent more likely to earn bachelor’s degrees.

Regulatory accountability can be a blunt instrument. A school’s overall positive grade can’t account for the individual students who aren’t benefiting, for whatever reason. It may not even be related to academics. Parents evaluate their children’s success and satisfaction with schools on far more criteria than test scores. They need a variety of options, and the means to exercise that choice.

To make informed choices, parents need as much knowledge about schools as possible – relevant data (graduation rates, curriculum, turnover in students and faculty, etc.), as well as consumer feedback, i.e., a Yelp or TripAdvisor for schools.

But they already know better than any technocrat what makes their child tick. Self-interest is a powerful motivator – and an effective antidote to the hobgoblins and phantasms aimed at undermining it.

Mitchell and Kamden Kuhn spent two years on a waiting list to adopt a child. The couple saw it as their mission to adopt a child in need from a developing country.

Editor’s note: This month, redefinED is revisiting stories that shine a light on extraordinary students. Today’s spotlight, first published in August 2016, tells the story of an orphaned, medically challenged child whose life was transformed by loving foster parents and a Gardiner Scholarship for students with special needs .

For nearly three years, starting before his third birthday, Malachi lived in an orphanage in Adama, in central Ethiopia. Born with spina bifida, a birth defect that causes leg weakness and limits mobility, he had to crawl across the orphanage’s concrete floors.

The orphans shared clothes from a communal closet and he rarely wore shoes causing his feet to become covered with callouses. At night he slept in a crib in a shared room with five other orphans. They ate communal meals prepared by their caretakers over a wood-burning fireplace. With his doctor more than an hour away in Addis Ababa, the capital, he rarely had access to much-needed medical attention.

His caregivers did their best with what little resources they had, but Malachi was only surviving. It seemed impossible that he would one day stand on his own — much less walk, or go to school.

All of that changed last year, when Malachi arrived in Florida where he now lives with two adoptive parents, and, with the help of a revolutionary scholarship program, has begun pursuing an education.

Kamden Kuhn and her husband, Mitchell, decided to adopt a child before they were married eight years ago. Their faith inspired them to seek out a child in need from a developing country.

“God has rewarded us,” she said. “We can attempt to show love in a similar way.”

The Kuhns spent the next two years on a waiting list for a healthy infant. As they waited, they realized they’d drifted from their mission to adopt a child in need.

Each month the adoption agency sent them a “waiting child list” full of older children who were struggling to find homes. One month, they received a description of a four-year old boy with spina bifida named Malachi.

The Kuhns talked to parents with children with special needs to learn about educational opportunities, insurance and medical care. One family friend told them about the Gardiner Scholarship, a state education savings account program for children with special needs. (Step Up for Students, which publishes this blog and pays my salary, helps manage the accounts of students on the Gardiner Scholarship program.)

After three years of searching, two trips to Ethiopia, mountains of paperwork and $42,000 in expenses, the Kuhns brought Malachi home to Ruskin, Fla. on Sept. 21, 2015.

They applied for the Gardiner Scholarship and enrolled him in Ruskin Christian School. Kamden Kuhn said the nearby public school was good, but she didn’t want her son pulled out of class time for therapy. She wanted Malachi to have the same amount of class time as the other students. The Kuhns used funds left over after paying his tuition to purchase after-school physical, occupational and behavioral therapy.

His mother said the therapists provided instruction and therapy through play.

“I’m not the best educator for my son,” Kuhn said. “But this allows me to shop around for the best educators and best therapists. I can decide what is best, because I know him best.”

Malachi needs a stable, predictable environment where he can thrive. His parents and the teachers at the school worked together as a team.

“He made so much progress in the first nine months,” Kuhn recalled. He quickly started to learn to speak English and to stand upright with the aid of a walker. Now stronger than ever, he uses a forearm cane to walk.

“Ms. Stacy helped me learn to walk, and Ms. Colleen helped me get in control,” Malachi said of his physical and occupational therapists. In a telephone interview, he said phonics is his favorite subject because he loves learning letters and how to put them together to make words.

One day, according to his mother, his class was learning about firefighters. As the children went into a field and pretended to battle make-believe blazes, Malachi’s walker got stuck. A teaching assistant (Ms. Shelly) carried him out to the other children, allowing him to join in the fun. He still recalls that day fondly.

“I like Ms. Nichter because she helps me, and I like Ms. Shelly because she carried me,” he said of his teachers.

Malachi has access to care and support that would have been unthinkable at a cash-strapped orphanage in one of the poorest countries in the world. Ethiopia’s per-capita gross domestic product ranks 208 out of 229 countries, according to the CIA. Still, it has a long history and is now home to one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. His parents say they hope he’ll learn more about his home country and take pride in his roots.

Now six years old, he is starting his second year on the Gardiner Scholarship at a new school, Holy Trinity Lutheran, after his family moved north to Tampa.

The Kuhns recently visited his new school to meet the teachers.

“I’m really excited,” he said about his new school.

“He’s been saying this nonstop all week,” his mom added.

Raising a child with special needs isn’t easy. In fact, “it’s way, way harder than we ever thought it would be,” said Kuhn. “But we are confronting the challenge, knowing the blessing that he is.”

Spina bifida can limit people’s physical mobility, but with proper support care they can often excel in school, participate in other activities, and lead full lives. Malachi has realized that anything is possible. Not content with just walking, he now dreams of soaring when he grows up. Asked about his future career goals, he said: “I want to drive an airplane!”