Editor’s note: William Mattox, director of the Marshall Center for Educational Options at the James Madison Institute and author of a new study related to this topic, provided this commentary exclusively for reimaginED.

Editor’s note: William Mattox, director of the Marshall Center for Educational Options at the James Madison Institute and author of a new study related to this topic, provided this commentary exclusively for reimaginED.

Any Florida education leader sitting down to watch tonight’s college football championship game may be tempted to bask in the glory of his or her own accomplishments. After all, Florida has become to K-12 education what the Alabama Crimson Tide has long been to college football – the standard by which everyone else measures themselves.

Florida recently received the nation’s No. 1 ranking in parental involvement in K-12 education according to the Parent Power Index, a state-by-state compilation from the Center for Education Reform. The title follows the Sunshine State’s recognition as No. 1 in K-12 education freedom by The Heritage Foundation.

And it adds to Florida’s recent year top rankings in state-by-state comparisons made by the American Legislative Exchange Council, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and others. Yet, all this success begs an important question: Could the accolades Florida keeps receiving prove to be what Alabama football coach Nick Saban likes to call “rat poison”?

Saban has memorably invoked this term whenever football analysts have lavished mid-season acclaim on his team. He fears that fawning praise will go to players’ heads and diminish their drive for sustained excellence. Saban’s 2022 team did nothing to ease his fears.

Alabama’s 2022 team received all sorts of glowing headlines early in the season when pollsters crowned them the prohibitive favorite to win it all. But as the season wore on, the Crimson Tide failed to make consistent improvements. Ultimately, the team finished out of the college playoffs and in a ho-hum bowl game against a three-loss Kansas State team.

Bah. Humbug.

How can Florida’s education leaders learn from the Crimson Tide’s 2022 cautionary tale and continue their drive for sustained excellence?

Three words: Keep making improvements.

First, Florida needs to keep making improvements in providing scholarship opportunities for K-12 students. More than two decades after Florida’s first school choice programs were created, some Florida students remain ineligible for scholarship assistance – even though their parents pay taxes and the state will fund their education if they attend a public school.

The Florida Legislature ought to fix that in 2023. School choice scholarships should be available to all students. Yes, every kid.

Second, Florida needs to keep making improvements by encouraging K-12 innovation. Specifically, Florida needs to greatly expand its flexible scholarship programs so that families can take advantage of all sorts of emerging educational options including microschools, learning pods, virtual learning programs and hybrid homeschools.

Thanks to the Naples-based Optima Foundation, Florida is home to the first-ever classical school using immersive technology. Wearing virtual reality headsets, students travel back in time to witness re-creations of famous historical events and debates. (You can read a reimaginED feature on the school here.)

Openness to creative innovation like this ought to be the rule rather than the exception in K-12 education. Expanding flexible scholarships, known as education savings accounts, can help Florida continue to immerse itself in educational progress.

Finally, Florida needs to keep making improvements in the way that it helps students from disadvantaged communities. Specifically, policymakers need to give attention to addressing what Harvard scholar Raj Chetty calls the dearth of “positive neighborhood effects” in many lower-income communities.

One way to do this would be for Florida to work with the federal government to transform the Title I program into a weighted scholarship that funds students, not systems. This would give strong families an incentive to remain in and help revitalize disadvantaged neighborhoods rather than fleeing to higher-performing school districts, as has been the historic pattern.

If Florida can keep making improvements, the state can continue to be a leader in K-12 education. It can continue to sustain the excellence it has demonstrated in recent years. And it can continue to offer the hope of a better future to more and more Florida students.

As tonight’s kickoff approaches, let’s hope Florida education leaders learn a lesson from the 2022 Crimson Tide. Let’s hope they heed Nick Saban’s warning about “rat poison.”

As public school leaders began delving into the details of what went wrong following last week’s release of dismal NAEP reports, Catholic school leaders paused briefly for a victory lap before looking into how they can continue to up their game.

As public school leaders began delving into the details of what went wrong following last week’s release of dismal NAEP reports, Catholic school leaders paused briefly for a victory lap before looking into how they can continue to up their game.

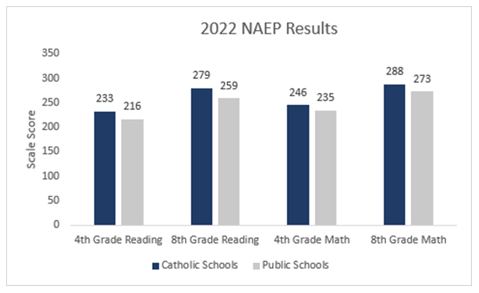

They had good reason to celebrate. Figures from the National Assessment of Education Progress, also known as the Nation’s Report Card, showed Catholic schools outperformed their public school counterparts in almost all categories.

The average score among fourth graders in Catholic schools was 233, 17 points higher than the national public school average, or about 1½ grade levels ahead. In eighth grade reading, the average score for Catholic school students was 279, 20 points higher than the national public school average, or about two grade levels ahead.

Although Catholic school students experienced a statistically significant 5-point drop in eighth grade math, Catholic school students’ average scores remained 15 points higher than the average scores of their public school eighth grade peers.

When broken down by race, Catholic schools showed significant gains since 2019. Achievement among Black students increased by 10 points (about an extra year’s worth of learning), while Black students in public schools lost 5 points.

On the eighth grade reading test, Hispanic students gained 7 points while Hispanic students in public schools lost 1 point.

Catholic schools led the nation for Hispanic achievement on each of the four tests and led the nation in Black student achievement on three of the four. They also ranked first in eighth grade reading and third in both fourth grade reading and fourth grade math for students who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch.

“Today, the divergence between Catholic schools and public ones is so great that if all U.S. Catholic schools were a state, their 1.6 million students would rank first in the nation across the NAEP reading and math tests for fourth and eighth graders,” wrote Kathleen Porter-Magee, superintendent of Partnership Schools, a management company that runs 11 Catholic schools in New York City and Cleveland.

(You can read her opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal here.)

State and local Catholic school scores were not released, but administrators praised the overall results, which they said reflected the benefits of a Catholic education.

“I’m not surprised,” said Father John Belmonte, superintendent of schools for the Diocese of Venice, which includes 16 Catholic schools in 10 Southwest Florida counties. He said while many public schools across the nation shut down for extended periods, Catholic schools remained open.

“Now you’re seeing the difference in-person education makes,” he said.

Enrollment in diocese schools was up 26% last year, with much of that due to what he called “COVID refugees” moving in from out of state to escape shutdowns. He also credited state education choice scholarship expansion, which granted automatic eligibility to children of law enforcement officers and military members

He said a common criticism of private schools is that they can be selective, while public schools must take all comers. However, the data showing that Catholic schools were near the top in learning outcomes for students receiving free and reduced-price lunch demonstrates their commitment to those who economically disadvantaged.

Chris Pastura, superintendent for the Diocese of St. Petersburg, which includes 46 schools in the Tampa Bay area, said he was “thrilled” with the results, which he reflected are a testament to how well Catholic schools handled the pandemic and their overall approach to education.

“It really underscores the power of Catholic schools and the power of education that looks to serve the whole child,” he said, adding that Catholic schools embed academics with the faith and hope that allow people to move through challenges.

Jim Rigg, superintendent of the 62 schools in the Archdiocese of Miami, was so delighted with the NAEP results that he sent a letter to teachers and staff at his schools to express his gratitude.

“We could cite many reasons for the success of our schools,” he wrote. “Catholic schools benefit from strong parent involvement, vibrant communities, and a commitment to serve the whole child. However, I know that the most important reasons our schools succeed is because of the talents, dedication and faith of our Catholic school teachers and other employees. You are our ‘secret sauce’, the real reason our schools rise above others.”

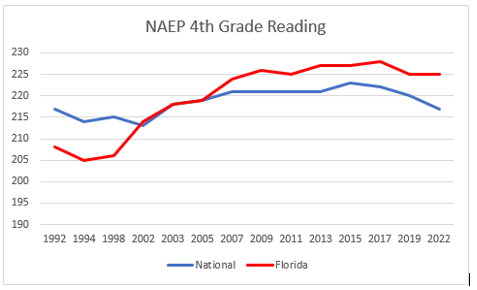

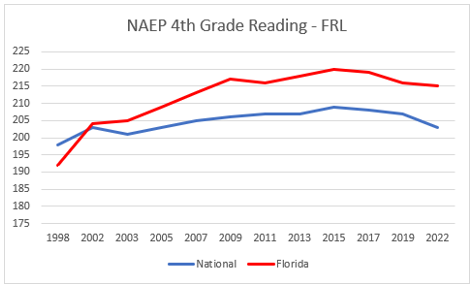

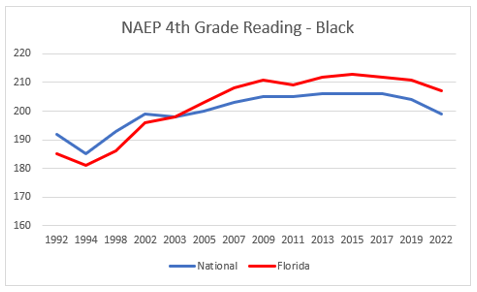

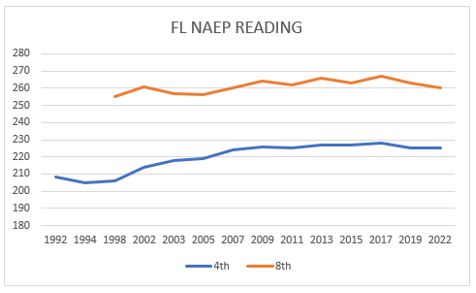

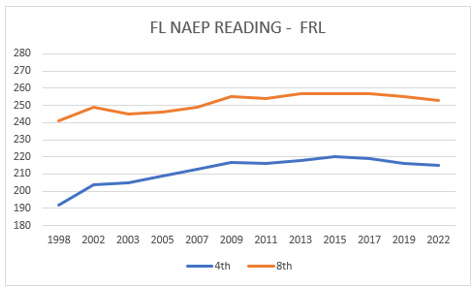

Results from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) aren’t pretty, but Florida does have some bright spots. The state’s students continue to excel at reading, especially when viewing the results demographically, and in particular, by free and reduced-price lunch eligibility, an indicator of poverty.

Results from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) aren’t pretty, but Florida does have some bright spots. The state’s students continue to excel at reading, especially when viewing the results demographically, and in particular, by free and reduced-price lunch eligibility, an indicator of poverty.

Comparing overall results isn’t entirely fair, since Florida is a majority-minority state, a term used to refer to a subdivision in which one or more racial, ethnic and/or religious minorities make up a majority of the population. Florida also has a larger than average low-income student population.

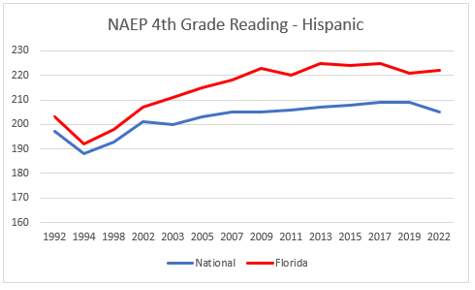

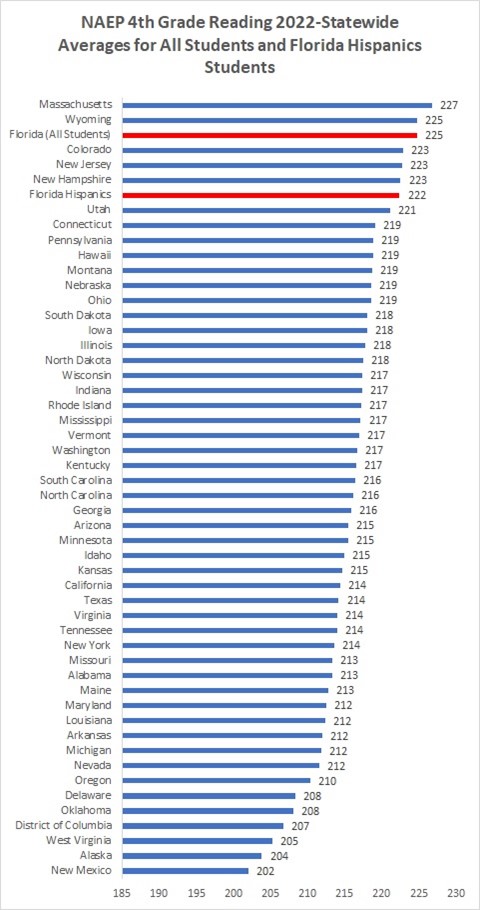

With that in mind, Florida’s fourth-grade Reading results continue to demonstrate that the Sunshine State punches above its weight, showing that the state’s efforts to improve education in elementary grades has paid dividends, allowing Florida to top the nation in NAEP rankings in those early grades no matter how you slice the data.

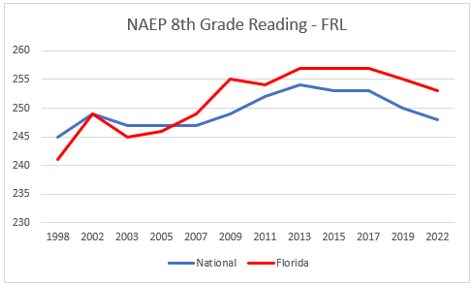

Florida’s low-income students had a modest decline during the COVID-19 pandemic, but that decline was much smaller than the 2017-19 decline. Nationally, low-income students suffered a far more severe decline in fourth-grade Reading outcomes to the point where Florida’s students are now a grade level ahead of their counterparts.

Florida’s low-income students had a modest decline during the COVID-19 pandemic, but that decline was much smaller than the 2017-19 decline. Nationally, low-income students suffered a far more severe decline in fourth-grade Reading outcomes to the point where Florida’s students are now a grade level ahead of their counterparts.

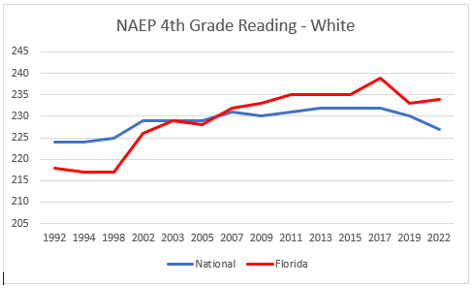

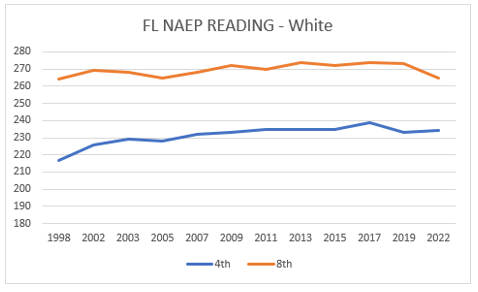

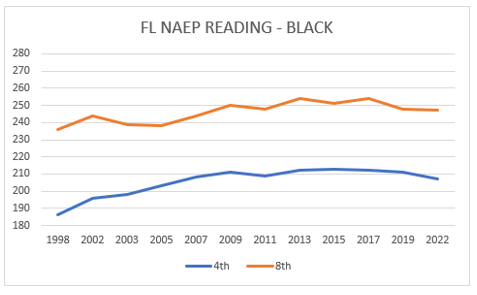

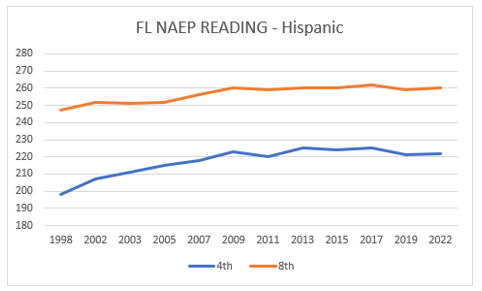

Florida’s fourth graders didn’t suffer as badly as the rest of the nation. White and Hispanic students in fourth grade bounced back from 2019 results, while Black students saw a decline that mirrored results of the rest of the nation.

Florida’s fourth graders didn’t suffer as badly as the rest of the nation. White and Hispanic students in fourth grade bounced back from 2019 results, while Black students saw a decline that mirrored results of the rest of the nation.

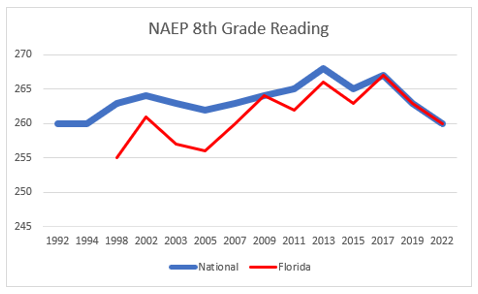

Florida’s fourth grade students are about a grade level ahead of students nationally. When adjusting for demographics and poverty, Florida ranks No. 1 in the nation for fourth grade Reading but drops to around eighth for eighth grade Reading. Without this adjustment for poverty and race, Florida’s eighth-grade Reading results appear to be just average.

Eighth grade Reading declines were sharp, but no worse than the national average. Remember, though, the national average is both whiter and wealthier than the average student in Florida.

Low-income student performance declines mirrored the rest of the nation, but economically-disadvantaged children are still better off in Florida than in the vast majority of states.

Low-income student performance declines mirrored the rest of the nation, but economically-disadvantaged children are still better off in Florida than in the vast majority of states.

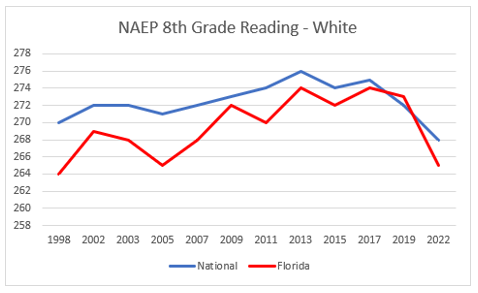

It’s impressive to see how big the drop was for Florida’s white eighth grade students between 2019 and 2022. Why this occurred is a mystery, but it is the driver behind Florida’s sharp (but entirely average) decline in eighth grade Reading results.

It’s impressive to see how big the drop was for Florida’s white eighth grade students between 2019 and 2022. Why this occurred is a mystery, but it is the driver behind Florida’s sharp (but entirely average) decline in eighth grade Reading results.

Florida’s white students saw a staggering 8-point drop from 2019, while the national average was a 4-point drop. This was far more severe than the decline for Hispanic and Black students in Florida and nationally.

Florida’s white students saw a staggering 8-point drop from 2019, while the national average was a 4-point drop. This was far more severe than the decline for Hispanic and Black students in Florida and nationally.

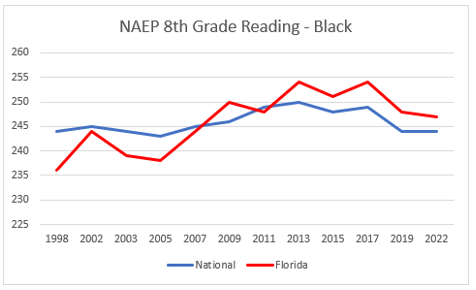

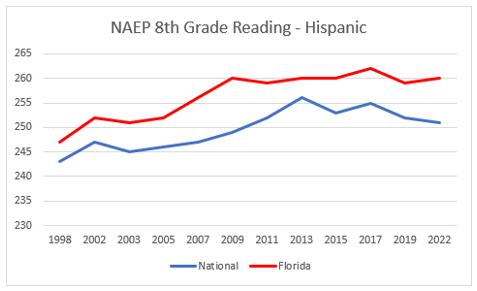

Both Black and Hispanic students continue to beat the national average on eighth grade Reading results.

Both Black and Hispanic students continue to beat the national average on eighth grade Reading results.

One final point: everything learned in fourth grade is a building block for later grades. Florida’s students don’t peak in fourth grade just because the state’s results top the charts. Florida’s fourth graders are, on average, a grade level ahead of their counterparts nationally.

One final point: everything learned in fourth grade is a building block for later grades. Florida’s students don’t peak in fourth grade just because the state’s results top the charts. Florida’s fourth graders are, on average, a grade level ahead of their counterparts nationally.

Without those early big gains in fourth grade, Florida’s eighth grade results would be much worse than “just average.” (And again, that “average” is compared to all incomes and races nationally, despite Florida’s status as a majority-minority state with a larger than average population of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.)

Florida’s students are still getting about a year’s worth of learning in a year’s time between fourth and eighth grades. On average, Florida students gained 35 points in four years, a roughly 3.5 grade level growth.

Low-income students gained 38 points between fourth and eighth grades, roughly four years’ worth of learning in four years’ time.

Low-income students gained 38 points between fourth and eighth grades, roughly four years’ worth of learning in four years’ time.

Florida’s white students are driving underperformance by eighth grade, gaining just 31 points between fourth and eighth grades, which is about three years of learning in four years’ time.

Florida’s white students are driving underperformance by eighth grade, gaining just 31 points between fourth and eighth grades, which is about three years of learning in four years’ time.

Florida’s Black students gained 40 points between fourth and eighth grades, meaning they gained a grade level of learning for each grade completed.

Florida’s Black students gained 40 points between fourth and eighth grades, meaning they gained a grade level of learning for each grade completed.

Meanwhile, Florida’s Hispanic students gained 38 points in four years, roughly a year’s worth of learning in a year’s time for each grade.

Meanwhile, Florida’s Hispanic students gained 38 points in four years, roughly a year’s worth of learning in a year’s time for each grade.

Coming up next week: the breakdown of the NAEP Math results.

Coming up next week: the breakdown of the NAEP Math results.

NAEP released 2022 state and large urban district data early this morning. Scores dropped in all four tested subjects (fourth and eighth grade math and reading) almost across the board. Nationally the drops were -3, -3, -5 and -8 points on fourth grade reading, eighth grade reading, fourth grade math and eighth grade math, respectively, from 2019. On these exams 10 points approximately equals a grade level of average progress, and the scores in 2019 were also generally down.

Florida’s scores fell in both math exams, held steady on fourth grade reading and declined modestly on eighth grade reading.

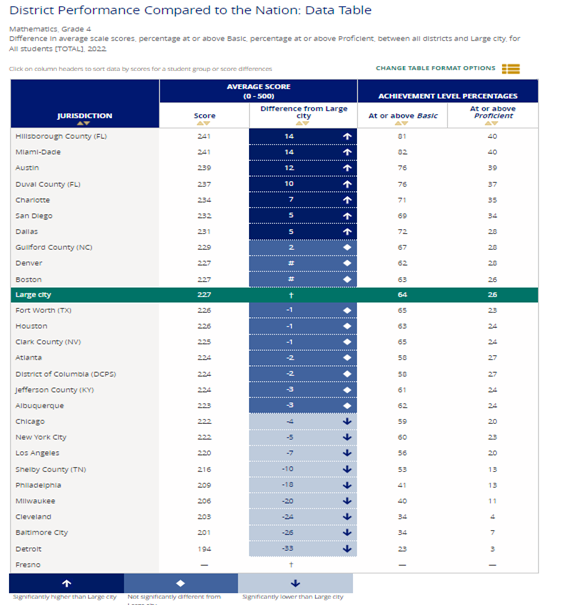

Some bright spots: Florida’s fourth grade reading performance still shines. For example, on the Trial Urban District Assessment (TUDA- the NAEP for select large urban districts) the three Florida districts ranked first, second and third with differences 14, 14 and 10 points above the national average for large cities nationwide. Florida students ranked third on fourth grade reading in 2022, and if Florida’s Hispanic students ranked seventh compared to statewide averages for all students.

Charter school students and students with disabilities also appear to be relative bright spots for Florida, but the overall challenge on the math front is considerable. And nationally the news is nothing short of a catastrophe, as you can see in the chart below by state:

If there is a silver lining here, it is that math is not as difficult to remediate as reading. Given these huge deficits and the even more gigantic amounts of unspent COVID-19 funding, let’s just say that a sense of urgency has been noticeably lacking. If you have children or grandchildren, I would advise you to get them to a math tutoring service ASAP- don’t give the system the chance to let them down again. Florida pioneered a micro-grant for the purposes of reading remediation; lawmakers would do well to do the same for mathematics.

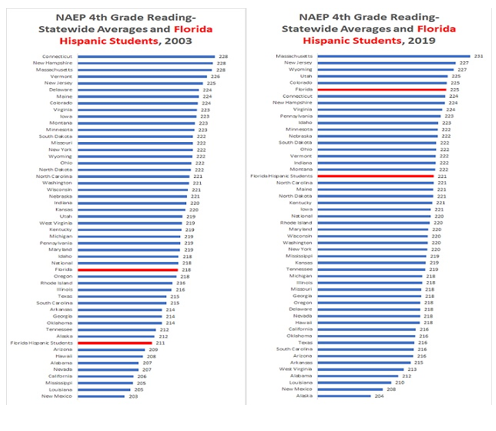

It is Hispanic Heritage Month, and Floridians have cause to celebrate a radical improvement in Hispanic literacy seen over the last two decades.

It is Hispanic Heritage Month, and Floridians have cause to celebrate a radical improvement in Hispanic literacy seen over the last two decades.

Quick reminder: Florida’s Hispanic students outscore most statewide averages on NAEP’s fourth grade reading test. Yes, the one given in English.

The chart on the left shows how Hispanic literacy already had looked promising in 2003; the chart on the right shows how the promise had unfolded into a full-blown rout by 2019.

If it humiliates you to see Florida’s Hispanic students outscoring your statewide average, and you’re not doing anything about it, you should feel humiliated. Back in the late 20th century, a non-profit dedicated to assisting Black students attend college coined the phrase “a mind is a terrible thing to waste.” This was true then, and it will become increasingly, acutely true in the future.

If it humiliates you to see Florida’s Hispanic students outscoring your statewide average, and you’re not doing anything about it, you should feel humiliated. Back in the late 20th century, a non-profit dedicated to assisting Black students attend college coined the phrase “a mind is a terrible thing to waste.” This was true then, and it will become increasingly, acutely true in the future.

If we are betting on the future, I’m going all in on the state that had a great deal of success in improving basic literacy.

Meanwhile, some of Florida’s fellow mega-states, like California, Illinois, New York and Texas, seem to have embraced the Judge Elihu Smails theory of education. (Smails was the comical bad guy in the 1980 comedy Caddyshack, played by actor Ted Knight, a pompous snob with a fondness for white pants, yachting caps and golf.)

Meanwhile, some of Florida’s fellow mega-states, like California, Illinois, New York and Texas, seem to have embraced the Judge Elihu Smails theory of education. (Smails was the comical bad guy in the 1980 comedy Caddyshack, played by actor Ted Knight, a pompous snob with a fondness for white pants, yachting caps and golf.)

One of his infamous lines: “Well, the world needs ditchdiggers, too.”

With the baby boomers reaching age 65 at the rate of 10,000 per day clip and sticking their children and grandchildren with their underfunded entitlement bills, the future needs all the help it can get. The baby bust that started in 2007 makes improved literacy rates even more vital.

The 2022 NAEP will be released in the next few weeks; stay tuned to this channel. I have a feeling the red line will be going higher up the list.

Geography lies at the heart of New York’s success almost as much as it does for the United States as a whole.

Geography lies at the heart of New York’s success almost as much as it does for the United States as a whole.

With the completion of the Erie Canal, water transport of goods from deep into the interior of the United States could reach New York City via the Great Lakes, the canal and then the Hudson. From New York City, they could reach the world.

Of course, it took money to finance such activities, and New York City became at first a national center of the finance industry. By the mid-20th century, New York City had become a global capital of finance and culture, primus inter pares among cities.

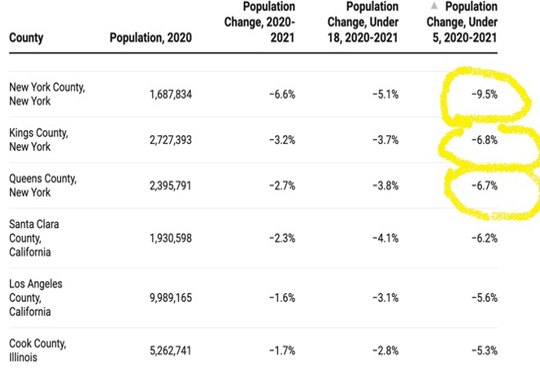

These days, however, we are witness to the city’s sad decline; the K-12 education situation continues to nudge the city ever further from its glorious past.

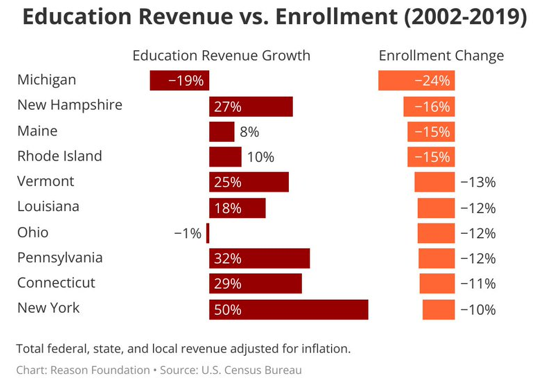

The decline started long before the pandemic. This chart from the Reason Foundation shows that New York’s statewide K-12 enrollment fell by 10% between 2002 and 2019, but inflation-adjusted K-12 spending increased by 50%. New Yorkers bore an ever-growing tax burden for a school system that enrolled fewer students over time.

The decline started long before the pandemic. This chart from the Reason Foundation shows that New York’s statewide K-12 enrollment fell by 10% between 2002 and 2019, but inflation-adjusted K-12 spending increased by 50%. New Yorkers bore an ever-growing tax burden for a school system that enrolled fewer students over time.

This considerable increase in the tax burden might have paid dividends if the average quality of schooling in New York had improved. Instead, the long-standing migration destination for New Yorkers – Florida – improved its K-12 outcomes despite relatively constrained spending.

New York’s failure to improve eighth grade reading achievement was not an isolated failure. The state failed to show much improvement in outcomes in any of the main NAEP exams. Thus, New Yorkers had fewer students educated at a 50% higher fiscal burden with little to no improvement in education quality.

Strangely enough, people began finding better value propositions in other states, especially Florida. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated many pre-existing trends, including the one where people noticed that it was not in their family’s best interest to live in New York.

James Q. Wilson in his 1975 book “Thinking About Crime” related how many American cities fell into a cycle of decline after the creation of the interstate highway system. As people gained the opportunity to work in a city but live in a suburb, the tax base, and perhaps just as crucial in Wilson’s view, the informal community policing practices that followed, caused cities to respond in two ways: they either raised tax rates to make up for the lost tax revenue or the cut services.

Regardless of the choice made, the effect was to alienate people and increase the lure of the suburbs. Many cities thus fell into a cycle of decline.

A third option and a path out of this dilemma went undiscussed by Wilson: Cities could innovate and provide better services for lower taxpayer costs. This, however, is precisely what the unions who play a powerful role in municipal elections wished to avoid at that time.

It is precisely what the American Federation of Teachers seeks to avoid in New York and elsewhere today. Perhaps New York will correct its course at some point, but in the meantime: Welcome to Florida!

Oliver Wiseman’s recent City Journal article on Miami paints an optimistic picture from urban America.

Oliver Wiseman’s recent City Journal article on Miami paints an optimistic picture from urban America.

Miami is the unofficial capitol of Latin America, and unlike many large cities Miami is politically competitive rather than mono-partisan. Wiseman describes anti-communism as being a part of Miami’s cultural DNA and Francis Suarez, Miami’s Republican Mayor, has become famous for attracting business to the city.

It seems to be working: both finance and tech firms have been moving in.

“We are a city that believes in capitalism,” Wiseman quotes Suarez. “That believes in innovation as a means of democratizing opportunities.” It seems to be working:

Away from the flashy tech hub sales pitch, he pushes an agenda that focuses on low taxes, combating homelessness, and encouraging school choice and a well-funded police department. In January, Suarez takes over as chairman of the Conference of Mayors, an organization of city leaders. From that position, he hopes to push his center-right brand of urban policy on a national stage.

Some of this, he concedes, is not replicable—palm trees wave outside his office, as if a reminder of the city’s natural advantages were needed—but part of it is. “Miami has changed in the last ten years,” says Suarez. “It’s become the prototypical city, the city that you want to be like.”

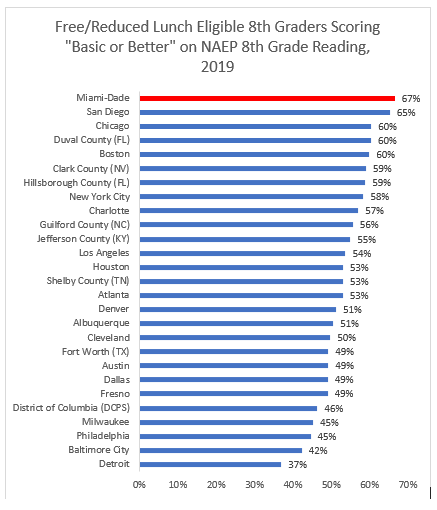

Many city leaders talk a good game on opportunity and class mobility, but then something gets lost in the execution. Miami however has scoreboard, such as the data from the Trial Urban Assessment NAEP that collects academic data from large cities.

Texans should note of where Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth and Austin rank on the below chart compared to Miami.

State Senator Ileana Garcia sums it up with a very telling quote: “What motivates us is freedom: freedom to live your life according to your values, freedom to do what you want with your money and freedom to live in a country where you don’t have to have government hovering over you and telling you what to do all the time.”

Miamians are living in America, they feel good, and they are helping themselves to your state’s talent.

I’ll take a Miami for my state por favor!

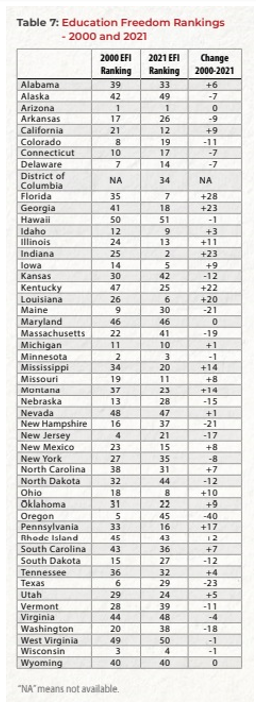

A recent editorial in the Wall Street Journal focused on the work of researchers at the University of Arkansas’ School Choice Demonstration Project that measured school choice environments in the states and Washington, D.C. The Education Freedom Index considered offerings for private school choice such as vouchers and tax credit scholarships, homeschooling, public school choice and charter schools.

A recent editorial in the Wall Street Journal focused on the work of researchers at the University of Arkansas’ School Choice Demonstration Project that measured school choice environments in the states and Washington, D.C. The Education Freedom Index considered offerings for private school choice such as vouchers and tax credit scholarships, homeschooling, public school choice and charter schools.

The original Education Freedom Index, written by Jay Greene in 2001 and published by the Manhattan Institute, captured broad elements of public-school choice, private choice and home-schooling, and found a positive statistical relationship between choice and state academic performance.

I had the opportunity to work with Greene and his associates Patrick J. Wolf and James D. Paul on the updated index. Once again, a positive association was found between education freedom and outcomes after controlling for other factors.

Journal editors were curious about how these regression coefficients might translate into student outcomes. They wrote:

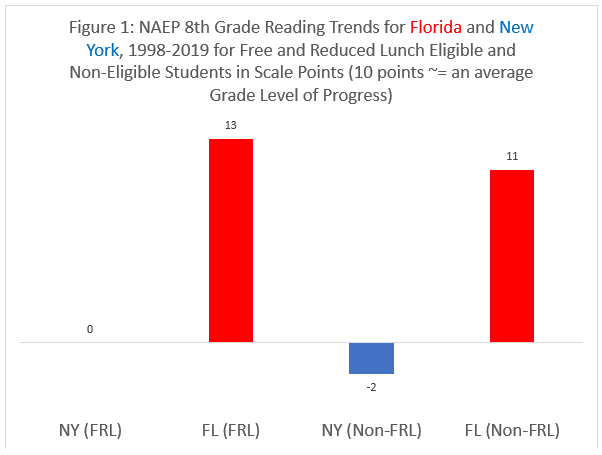

How could this translate in the real world? Study author Jay Greene says to consider a student about to enter kindergarten in New York, which ranks 35th in the Education Freedom Index.

If his family chose to move to Florida—which ranks 7th—for the child’s K-8 education, the child would climb 10 points on the NAEP (e.g., to the 60th from 50th percentile in achievement) by the time he reached eighth grade compared to if he had stayed in New York. If the family moved to Arizona, the child would see an 18-point improvement. That’s using the researchers’ most conservative model.

Is this possible?

Outside evidence points in this direction (discussed below) but also the need for caution. Many factors influence academic achievement, both within school and outside of school. Scholars have, for instance, begun to quantify the level of education enrichment spending going on in America. Wealthy families were spending more than $9,000 per child per year in 2006.

We were not able to control for this or for other potential factors in the analysis. New York is the home to far more well-to-do families than either Arizona or Florida, and it is impossible to estimate the role this and other outside factors play in achievement.

We also don’t understand the lags involved between policy changes and outcomes changes. Arizona ranked first in the 2001 index and first again in 2021. Indiana ranked second in 2021, but Indiana’s choice programs are much younger than Arizona’s. Choice in Arizona debuted during the first Clinton administration; it came much later in Indiana.

Divining the drivers of academic achievement is more like a mystery with clues than a science lab with test-tubes. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s warning should always be borne in mind: “It is quite possible to live with uncertainty, with the possibility, even the likelihood that one is wrong. But beware of certainty where none exists. Ideological certainty easily degenerates into an insistence upon ignorance.”

In that spirit, I will note there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in any regression analysis.

With that said, both Arizona and Florida made large amounts of academic progress during the period between the two Education Freedom Index studies, New York not so much despite spending far, far more per pupil than either. Arizona’s choice system may have (uniquely?) reached a point of being primarily driven by school districts.

Arizona has the nation’s largest charter school sector at 20% of students, but district open enrollment transfers outnumber charter students nearly two to one in a study of enrollment patterns in the Phoenix area – 31% for open enrollment to 16% for charter schools. Arizona may have achieved, after decades and multiple policies, a sort of escape velocity relative to other states.

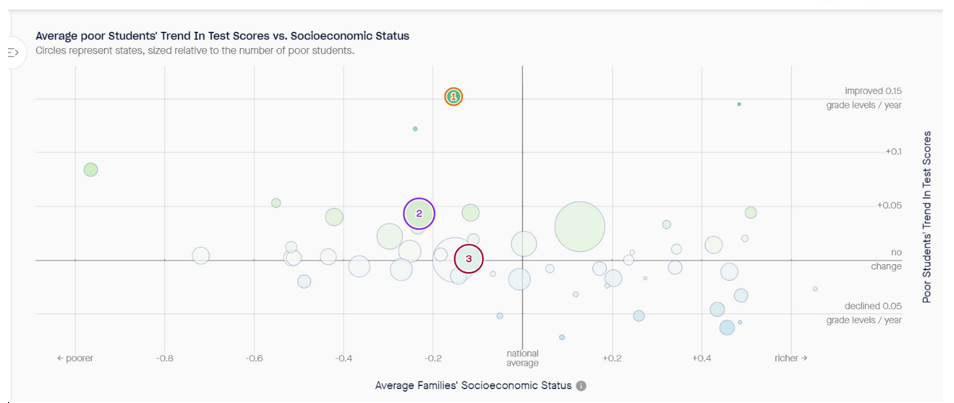

The chart below shows the trend in test scores of low-income students in grades 3-8 versus socioeconomic status between 2007 and 2018.

The reader should note that this period starts after Florida’s sizeable improvement in NAEP scores between the late 1990s and 2007 but covers the period of Arizona’s NAEP surge (2009-2015 with mixed results after 2015). If this chart had been available for 1998 to 2009, Arizona and Florida’s positions likely would be reversed. New York’s NAEP scores, meanwhile, show a broad pattern of stagnation and decline after 2003.

The horizontal axis measures the relative socio-economic status of low-income students in each state (most disadvantaged in Mississippi on the far left, most advantaged in New Hampshire on the far right). The vertical axis measures the trend in academic achievement for low-income students in percentages of a grade level gain or decline per year.

The average poor student in Arizona (1) gained .15 grade levels per year during this period, the nation’s highest. Low-income students in Florida (2) gained .04 per year grade levels per year, in New York (3) zero.

See: https://media.tenor.com/images/82136cbb2661bfbc7f079bb3cab40b97/tenor.gif

In New York, high demand charter schools seeking to create more seats for students must battle a mayor determined to make life tough for them. Even in Arizona, the pace at which high demand district schools expand or replicate has been glacial (although that may be changing), and charter schools face practical obstacles like paying for facilities out of operating budgets while receiving fewer public dollars per pupil.

Arizona parents practice frontier justice style accountability with charter schools, closing them down without pity if they don’t desire them. Districts, however, keep many low-demand schools open, with school boards fearful of community backlash accompanying a closure.

A similar political dynamic keeps districts from expanding or replicating high demand schools; the low-demand schools in the district feel threatened by it, keeping it off the table for consideration in most districts. The problem, as always, lies with politics. The status quo is deeply flawed and inequitable, but powerful groups benefit from inertia and resist change.

No state has yet captured anything close to the full potential benefits of choice. The struggle continues.

In the meantime, New York families should take the Wall Street Journal’s hint and move to Arizona or Florida. Super high-cost schools that do too little to teach kids suit certain interests just fine, but they are a terrible deal for you as a taxpayer and parent.

The Manhattan Institute published a study by Jay Greene in 2001 called the Education Freedom Index, which created a state-by-state comparison featuring measures of state charter school sectors, private choice, homeschooling and ease of transfer between districts. The study found a positive correlation between a state’s Education Freedom Index and academic performance.

The Manhattan Institute published a study by Jay Greene in 2001 called the Education Freedom Index, which created a state-by-state comparison featuring measures of state charter school sectors, private choice, homeschooling and ease of transfer between districts. The study found a positive correlation between a state’s Education Freedom Index and academic performance.

Some 20 years later, I had the opportunity to work with Greene and his associates Patrick J. Wolf and James D. Paul to update the index. What we see are some big moves up and down the list, one consistent leader, and, once again, a positive correlation between the index and academic performance.

The rankings in both 2000 and 2021 are presented in this graphic:

A few things to note: A great deal has changed since 2000. Arizona ranked No. 1 in 2000 based on a liberal and growing charter school sector and the early stirrings of private choice. A state with the amount of choice exercised in the Arizona of 2001, however, probably would rank as middling in the 2021 rankings. While Arizona ranked first in 2001 and first in 2021, the amount of choice being exercised by Arizona families today is far greater than it was in 2001.

A few things to note: A great deal has changed since 2000. Arizona ranked No. 1 in 2000 based on a liberal and growing charter school sector and the early stirrings of private choice. A state with the amount of choice exercised in the Arizona of 2001, however, probably would rank as middling in the 2021 rankings. While Arizona ranked first in 2001 and first in 2021, the amount of choice being exercised by Arizona families today is far greater than it was in 2001.

A recent release of data from the Stanford Opportunity project found Arizona students had the highest rate of academic growth both overall and for low-income students between 2007 and 2018. The predictions of doom which routinely accompanied each expansion of choice in Arizona are impossible to square with Arizona’s actual record of improvement.

Florida gained more than any other state in the rankings, moving from 35th in 2001 to 7th in 2021. We can’t firmly understand the relationship between education policy and outcomes, the lags such policies have before influencing outcomes, and associated mysteries. Life doesn’t often happen in a random assignment study, after all.

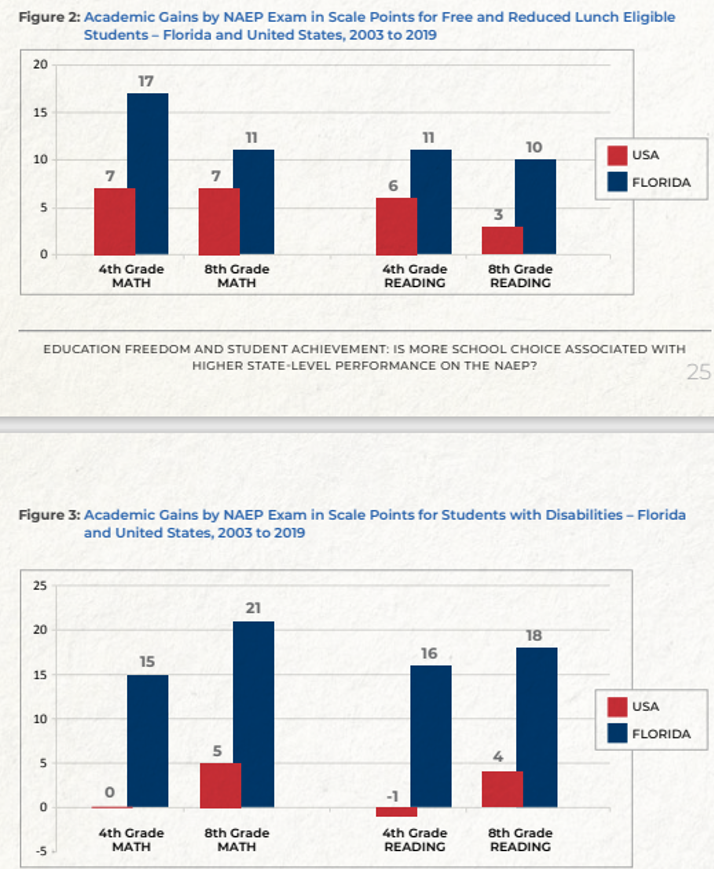

The two student populations with the most choice in Florida during the period between the studies – low-income students and students with disabilities – show the outsized progress on NAEP compared to the national average.

Check out the study, judge for yourself, live long and prosper.

Check out the study, judge for yourself, live long and prosper.

Editor’s note: This commentary, which compares Kentucky’s scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress to Florida’s, appeared earlier today in the Paducah Sun and was circulated nationally by the American Federation for Children.

Editor’s note: This commentary, which compares Kentucky’s scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress to Florida’s, appeared earlier today in the Paducah Sun and was circulated nationally by the American Federation for Children.

Does offering parents the option of sending their children to public charter schools or providing them with scholarships to assist with private school tuition harm public education?

No, solidly no.

But the correct answer is solidly “no” if you’re interested in the facts offered by credible sources like the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), known as “the nation’s report card.”

Just for fun, let’s try doing something far-left opponents of educational liberty rarely do: Consider unvarnished history and accurate comparisons of Kentucky, which offers no parent-controlled school choice, with other states that have such alternatives.

Consider, for example, the difference in educational trajectories between Florida and Kentucky since the early 1990s when neither state had school choice offerings and now, when nearly half a million students in the Sunshine State are being educated in public charter and private schools — including more than 100,000 via scholarship tax-credit policies — chosen by their parents rather than assigned by bureaucrats.

If school choice opponents’ theory that offering parent-controlled options on where to educate their children decimates public education holds up, shouldn’t Florida’s public system be devastated by now?

Yet, the NAEP indicates the opposite has occurred, sometimes even in dramatic fashion.

In 1992 — four years before Florida passed its first school choice law, which was a charter school bill — 26 other states outscored the Sunshine State’s fourth graders in reading while only four states and Washington, D.C., performed more poorly.

Flash forward to 2019, where only one state scored higher than Florida while 32 others and D.C. finished lower.

Similar shifts occurred in fourth-grade math and eighth-grade results in these same subjects.

While Florida was implementing a multitude of school choice policies while also improving its educational outcomes, Kentucky’s academic trajectory remained stagnant and — relative to other states — even declined in some academic areas.

To continue reading, click here.