The passage of HB1, a bill which makes all Florida children eligible for education choice, will benefit low-income children remaining in public school. Arizona’s experience illustrates how this process works.

The passage of HB1, a bill which makes all Florida children eligible for education choice, will benefit low-income children remaining in public school. Arizona’s experience illustrates how this process works.

While choice advocates are celebrating a wave of universal ESA program passages in 2022 and 2023, Arizona lawmakers first passed a form of universal choice in 1994. That was the year that the Legislature passed the nation’s most liberal charter school law and a statute on district open enrollment.

The law required districts to have an open enrollment policy and forbade charging tuition to open-enrollment students. In 1997, the Legislature passed a third universal choice program in the form of the nation’s first scholarship tax credit program. Funding for this program grew over time but remained limited.

The main impact of the tax credit program probably lies in having allowed more private schools to remain open despite the advent of charter schools. Arizona charter schools became very popular, and crucially, were geographically diverse. Arizona has urban-focused charter schools, but charter school models also were embraced in suburban and rural areas of the state.

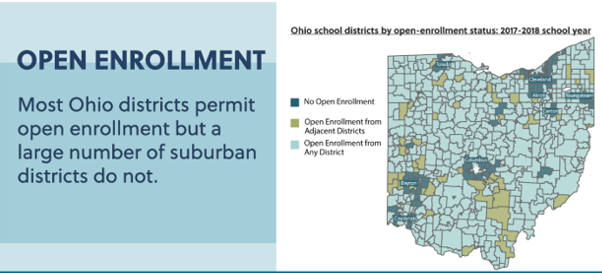

Open enrollment would not become a form of universal choice unless the districts chose to participate.

It is worth noting that in many states with voluntary open enrollment, the suburbs do not participate. See, for instance, this map from Ohio created by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

In 2017-18, every urban area in Ohio was surrounded by suburban districts choosing not to participate in open enrollment. Meanwhile, in Arizona, the growth of choice and the advent of the Great Recession made non-participation in open enrollment untenable.

In 2017-18, every urban area in Ohio was surrounded by suburban districts choosing not to participate in open enrollment. Meanwhile, in Arizona, the growth of choice and the advent of the Great Recession made non-participation in open enrollment untenable.

Arizona has long boasted the nation’s largest statewide charter school sector as a percentage of total enrollment. When the Great Recession hit, statewide enrollment growth stalled for the first time since World War II, and an abundance of suddenly inexpensive property hit the market.

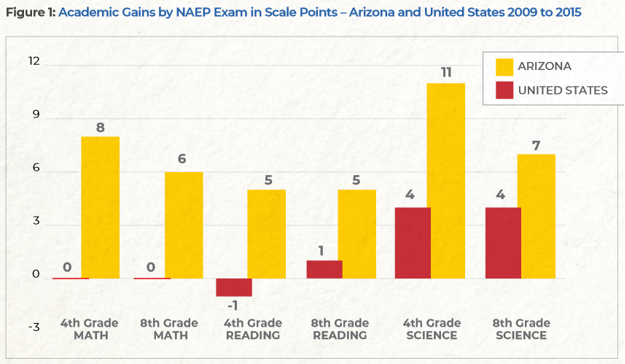

Charter enrollment surged, as did Arizona’s NAEP scores:

Arizona charter schools and private choice deserve credit for this surge, but in part, indirectly. In combination with the fact that enrollment growth stalled, they opened the suburban districts to open enrollment. In the Phoenix area, open-enrollment students outnumbered charter students almost two to one.

Arizona charter schools and private choice deserve credit for this surge, but in part, indirectly. In combination with the fact that enrollment growth stalled, they opened the suburban districts to open enrollment. In the Phoenix area, open-enrollment students outnumbered charter students almost two to one.

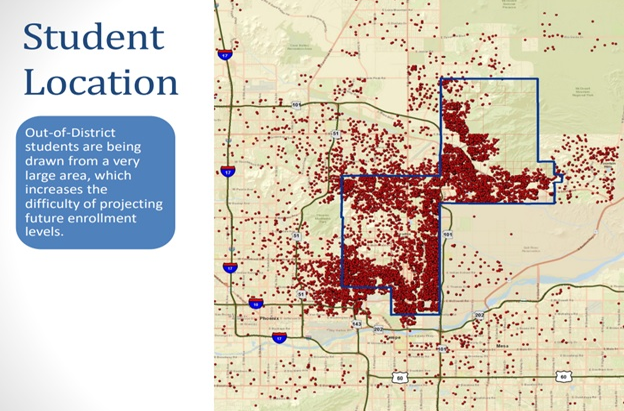

The first image in this post is an enrollment map of Scottsdale Unified. Each red dot is a student, and the blue line is the district attendance boundary. Scottsdale Unified enrolls 4,500 students from outside the district because 9,000 students who live inside the boundary go to school somewhere else – other districts, charter schools, private schools and home schools.

In combination, the competitive pressure of these options transformed Scottsdale Unified from a guarded fortress into a choice operator.

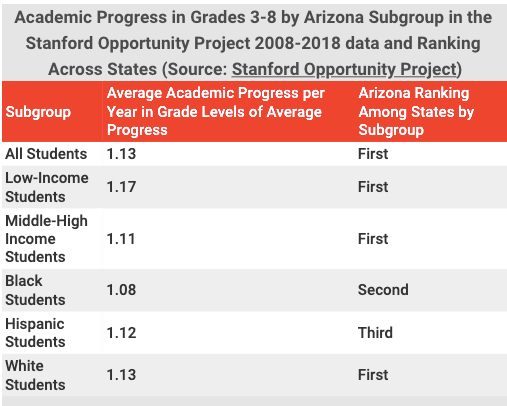

Florida lawmakers have laid the groundwork for a dynamic system of schools in which families collectively will shape which schools expand, which replicate, and which lose students. This model worked very well for Arizona students, including for disadvantaged subgroups.

Austrian and British economist and philosopher Friedrich August von Hayek, who was known for his defense of classical liberalism and free-market capitalism against socialist and collective thought, wrote:

Austrian and British economist and philosopher Friedrich August von Hayek, who was known for his defense of classical liberalism and free-market capitalism against socialist and collective thought, wrote:

“Our freedom of choice in a competitive society rests on the fact that, if one person refuses to satisfy our wishes, we can turn to another. But if we face a monopolist we are at his absolute mercy.”

It is vital to give disadvantaged students access to private and charter schools, but if you really want to improve their rate of learning, you also need to give them access to leafy suburban district schools. The embrace of universalism in our choice programs represents a major advance for low-income students.

Florida charter school students are out-scoring and out-gaining their traditional public school counterparts in more than 150 comparisons on the state’s standardized tests, according to a state-mandated report released by the Florida Department of Education Thursday.

Florida charter school students are out-scoring and out-gaining their traditional public school counterparts in more than 150 comparisons on the state’s standardized tests, according to a state-mandated report released by the Florida Department of Education Thursday.

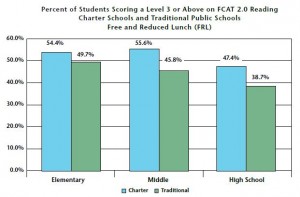

In 156 of 177 comparisons, charter school students scored higher, made bigger gains and had smaller achievement gaps.

The department compared the two sectors by looking at students overall, and by comparing white, black, Hispanic, high-poverty and disabled students, as well as English language learners. It broke down results into elementary, middle and high school categories.

The state based its analysis on more than three million scores from last year's reading, math and science FCAT tests and Algebra I end-of-course exam. Only students who attended traditional public schools or charter schools for the entire year were included. The report did not break down results by district.

Charters did particularly well with low-income middle schoolers. In reading, 55.6 percent of FRL kids in charter middle schools scored at grade level or above, compared to 45.8 percent for their traditional school peers. In math, the corresponding percentages were 54.8 and 44.5.

DOE press release here. Initial coverage from Gradebook and South Florida Sun Sentinel.

Tweaks coming to teacher evals? Gradebook: “Patricia Levesque, executive director of Jeb Bush's education foundation and a key voice in state education legislation, meanwhile, is floating a draft bill that would alter the evaluation system, too. She sent an e-mail to superintendents last week seeking input.”

Tony Bennett on charter schools. In a Q&A with the Orlando Sentinel, Bennett is asked whether lawmakers should tighten scrutiny on charter schools. His response: “When the charter movement began, the intent of charter schools was to trade increased freedom and flexibility for a higher level of accountability. Somewhere along the way, we lost track of that, and in too many cases, charter schools are held to lower standards than traditional public schools.”

Arming teachers? Teachers don’t like the idea, floated in the wake of Newtown, reports the Tampa Bay Times. Miami Herald columnist Fred Grimm agrees. Brevard schools go into lockdown after a man makes threats referencing Newtown, reports Florida Today. Rumors of violence in Hillsborough, reports the Tampa Bay Times and Tampa Tribune. More security discussions in Broward, reports the Miami Herald. A stranger trespassing on an Alachua middle school campus raises questions, reports the Gainesville Sun. Florida parents are among those ordering stacks of $300 bulletproof backpacks, reports the Orlando Sentinel. (Image from americablog.com). “Schools can’t be prisons,” editorializes the Pensacola News Journal.

Arming teachers? Teachers don’t like the idea, floated in the wake of Newtown, reports the Tampa Bay Times. Miami Herald columnist Fred Grimm agrees. Brevard schools go into lockdown after a man makes threats referencing Newtown, reports Florida Today. Rumors of violence in Hillsborough, reports the Tampa Bay Times and Tampa Tribune. More security discussions in Broward, reports the Miami Herald. A stranger trespassing on an Alachua middle school campus raises questions, reports the Gainesville Sun. Florida parents are among those ordering stacks of $300 bulletproof backpacks, reports the Orlando Sentinel. (Image from americablog.com). “Schools can’t be prisons,” editorializes the Pensacola News Journal.

More contracting issues. Four employees in the Division of Blind Services, which is under the Department of Education, are ousted after an audit reveals a sweetheart deal in the works over a contract, reports the Tampa Bay Times.

A day in the life. Orlando Sentinel columnist Beth Kassab spends a day with a teacher.

More poor kids. In Broward and Palm Beach counties, reports the South Florida Sun Sentinel.

Budget cuts. Brevard Superintendent Brian Binggeli recommends $39 million in cuts in the wake of a failed sales tax referendum. Florida Today.

Fallout over LGBT vote. SchoolZone.

Editor's note: Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill wrote the following letter, which was published this morning in the Tampa Bay Times. It's in response to this Times editorial about testing for students in Florida's tax credit scholarship program and recent comments from Gov. Rick Scott. Some recent news stories have also suggested that testing for scholarship students is limited or nonexistent.

Florida's public education system is so rich with learning options that last year 1.3 million students chose something other than their assigned neighborhood school. So the debate about how best to hold these diverse programs accountable for student progress is important.

Florida's public education system is so rich with learning options that last year 1.3 million students chose something other than their assigned neighborhood school. So the debate about how best to hold these diverse programs accountable for student progress is important.

Unfortunately, the manner in which the Times questioned testing for one of those programs — a Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income students — was incomplete and misleading. While it is true scholarship students are not required to take the FCAT, that doesn't mean the test most of them take annually, the Stanford Achievement, is irrelevant. This test is considered the gold standard in national exams, and has now been administered for six years with two consistent findings: 1) The students choosing the scholarship were the lowest performers in their district schools; and 2) They are achieving the same test gains in reading and math as students of all incomes nationally.

The expansion of options such as magnet programs, charter schools, virtual schools and scholarships for low-income children strengthens public education. These options all undergo rigorous academic evaluation, and the new national Common Core standards will hopefully make comparative evaluations even easier for parents and the public.

Ryan Wallace left his big, cliquish high school last spring for The Foundation Academy, a non-denominational Christian school with vegetable gardens and an aquaponic farm. “I wanted a chance to try something new,’’ said Ryan, now a 17-year-old junior planning a dodge-ball fundraiser for his class president campaign.

Boys in Aaron Unthank's single-gendered fifth- and sixth-grade class learn from each other, too. The setup gives Unthank more freedom to cater classes to meet boys' learning styles.

Twelve-year-old Marc’Anthony Acevedo came to the academy as a second-grader after being bullied at his old school. This year, he’s part of a single-gendered class of fifth- and sixth-grade boys. “Sometimes we have arguments, but we get over it,” he said. “We’re all friends.’’

For Cori Hudson, the Foundation was his last shot at a diploma. He messed up at the school district’s option of last resort. “I come to school every day now,’’ said the 16-year-old. “I feel like school is the most important thing to me.’’

These transformations are exactly what principal Nadia Hionides hoped for when she started the academy near Jacksonville Beach, Fla. nearly 25 years ago.

With a style that’s part Montessori, part Waldorf, the Foundation offers hands-on, project-based learning with a college-preparatory curriculum based on the philosophy that everyone learns differently.

The school has 280 students in kindergarten through 12th grade; 100 are in high school. They share a 23-acre campus that Hionides and her husband, a ship deck builder and painter, bought in 2008 for $600,000. The couple spent another $5 million for eight, prefabricated steel structures, which include a front-office foyer where the floor is made from vinyl records.

Tuition starts at $6,000 a year. But 81 students receive tuition assistance from Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that administers Florida’s tax-credit scholarship program for low-income kids and co-hosts this blog.

The academy separates students into groups of two grade levels - kindergarten and first-graders, second- and third-graders, etc.

“Because that’s real life,’’ Hionides said. Also, “they push each other to shine.’’

It seems to work in the fifth- and sixth-grade boys’ class – for the students and their teacher.

“It’s fantastic,’’ said Aaron Unthank, a longtime private school music teacher and baseball coach. “There’s a different kind of camaraderie as a class and there’s a lot more freedom I have as a teacher to talk about guy things.’’

The younger boys learn from the older boys, and the older boys gain confidence, Unthank said. He paraphrased Einstein: “You don’t know a thing well enough unless you can talk about it.” (more…)

More Broad Prize coverage. As we noted yesterday, the Miami-Dade school district won this year’s Broad Prize, which goes to the urban district with the most academic progress. More from the Orlando Sentinel, Christian Science Monitor, Associated Press, Education Week. The Palm Beach school district was a finalist, which is also impressive. All this is more reason to routinely compare achievement data district by district in Florida. Also worth noting: Miami-Dade is a poster child for the new definition of public education, with a broad menu of learning options and huge numbers of parents embracing them.

Charter school issues in Volusia. The Volusia school board approves improvement plans for two F-rated charter schools, reports the Daytona Beach News Journal.

PTA doesn’t like it. The Florida PTA pans the Board of Education’s decision to set steeper improvement goals for low-income and minority students, reports the Gradebook blog.

More on Amendment 8. The Tampa Bay Times gets credit for going into detail about the legal case that’s at issue here – a case that has nothing to do with vouchers. ICYMI, our take on Amendment 8 here and here.

So the Democrat supports vouchers? In this state senate race in Central Florida, yes, notes the Orlando Sentinel.

For the Miami-Dade school district, the fifth time's the charm. After being a finalist four other times, Florida's biggest school system finally won the Broad Prize in education today, given to the urban district making the most progress in student achievement. "Miracles are possible, even when you have to wait five years," Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said as he accepted the award, according to the Miami Herald.

For the Miami-Dade school district, the fifth time's the charm. After being a finalist four other times, Florida's biggest school system finally won the Broad Prize in education today, given to the urban district making the most progress in student achievement. "Miracles are possible, even when you have to wait five years," Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said as he accepted the award, according to the Miami Herald.

The prize is well deserved. Miami-Dade has a greater percentage of low-income and minority students than any big district in Florida. And yet, as we've noted many times on redefinED (like here and here), no big district has made bigger gains over the past decade. The judges at the Broad Foundation took note. So did U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan: "I commend the entire Miami-Dade community for establishing a district-wide culture of results that empowers teachers and students, puts more resources into helping children in the lowest-performing schools, and is helping narrow the opportunity gap."

Carvalho listed a number of strategies to explain the district's success, including a focus on teacher quality and struggling schools, and an expansion of learning options. All of those reforms together helped lift the kids in Miami-Dade. All of Florida should be proud.

As a group, low-income students struggle more than their wealthier peers. But in Florida, poor kids in some districts do a lot better than poor kids in others.

In Seminole County, for example, 56 percent of third graders eligible for free- and reduced-price scored at grade level or above on this year’s FCAT reading test, according to new state Department of Education data. In Duval County, meanwhile, 39 percent did. Among the state’s biggest districts, Seminole has one of the lowest rates of low-income kids. But so does Duval. And the low-income kids in Miami-Dade, which has the highest rate (nearly 20 percentage points higher than Duval), easily outpaced their counterparts in Duval. They did so in every tested grade, by an average of nine percentage points.

So what gives?

I’m not sure. But I think it’s worth a closer look.

We compare schools to each other so we can learn from those that make more progress. Ditto for states. Education Week’s annual Quality Counts report puts states side by side. It’s thoughtful and useful. It’s time for a similar spotlight on Florida school districts, which include some of the nation’s largest urban districts and an average enrollment among the top 10 of 165,000 students. Anybody could take the lead in setting that up – the press, parent groups, researchers, lawmakers, state education officials, maybe even the districts themselves.

Even with state mandates, districts have considerable leeway. Taking a closer look at achievement data district by district would spark more discussion about which ones are employing policies and programs that make the biggest difference for kids. The variation is endless. Some districts put more disability labels on minority students. Some put a premium on career academies. Some focus on principal development. Some have stronger superintendents. Some face more competition from charter schools and tax credit scholarships. How do things like that factor into district-to-district gaps? I’m sure it’s difficult to sort one from another, and impossible to draw definitive conclusions. But we won’t develop better hunches without looking at the data and talking about it.

A deeper dive into FCAT scores is one place to start. Most of the data I’m referring to is posted every year by the DOE, a few months after FCAT scores are released in late spring and early summer. It’s fascinating stuff – a breakdown of scores by district, subject, grade, FCAT level – and by all kinds of subgroups. I’ve talked to enough bona fide researchers about these numbers to know they raise fascinating questions.

Take Duval again. (more…)

Florida’s next education commissioner will inherit a job that makes juggling chainsaws look easy. He or she must get under the hood of a complicated accountability system, ride herd on a historic shake-up of public education, dodge slings and arrows while walking a political tight rope and leap tall buildings in a single bound.

Florida’s next education commissioner will inherit a job that makes juggling chainsaws look easy. He or she must get under the hood of a complicated accountability system, ride herd on a historic shake-up of public education, dodge slings and arrows while walking a political tight rope and leap tall buildings in a single bound.

And yet, the job remains so compelling. Florida is the nation’s most promising bridge to an education system that can more fully give teachers and parents real power to help kids live out their dreams. In the last 10 to 15 years, no state has focused more on the low-income and minority students who are now a majority in Florida public schools. Simultaneously, no state has opened the door more to alternative learning options – options that have both empowered parents and multiplied the potential for educators to innovate. The result has been both dramatic and nowhere near enough. The next commissioner must find ways to continue the momentum.

To that end, we hope he or she can nimbly rotate hats long enough to also assume the role of explainer-in-chief. We know this won’t be easy; education reformers in Florida operate in an environment that is particularly tense and, in the past couple of years, has become downright ugly. But we can’t help but think that maybe, just maybe, the temperature will drop a few degrees if fair-minded people can be persuaded that not every education idea and not every education reform is a zero-sum proposition. Sometimes, they really can work in harmony with the other parts.

This is especially true with school choice. The sincere goal here isn’t “privatization,” it’s personalization. It’s about expanding options so more kids can be matched with settings that maximize their potential, and yes that includes private and faith-based options.

There’s no reason, and so far in Florida no demonstration, that these options have to come at the expense of traditional schools. It’s entirely possible – and many of us think it’s absolutely necessary – to support traditional public schools at the same time we push for additional options that, for individual students, may work better. (more…)

From the better-late-than-never file:

The percentage of Florida students eligible for free- and reduced-price lunch rose for the fifth straight year last year to 57.6 percent, according to the state Department of Education.

In total, 1.54 million of the state’s 2.69 million students were eligible, marking the third straight year a majority of Florida students reached that threshold, says a report posted on the DOE web site over the summer (I stumbled on the latest numbers over the weekend, and as far as I can tell, no traditional news outlets have reported them).

The report shows 78.7 percent of black students were eligible for free- and reduced-price lunch last year, compared to 71.5 percent of Hispanic students and 38.2 percent of white students.

Among the state’s biggest districts, Miami-Dade led with the highest percentage, at 71.9 percent, followed by Polk at 68.3 percent and Lee at 64.2 percent.

Since the 2003-04 school year, Florida schools have also been majority minority. Last year, 57 percent of Florida students were minorities.

Despite the challenging demographics, Florida has over the past 10 to 15 years been among the leading states on key academic indicators, including progress on NAEP, performance on Advanced Placement tests and improvement in graduation rates.