ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. – Life, it’s often said, is what happens when you’re making other plans.

Tasia Mathis planned on joining the U.S. Navy Reserve. Then her grandmother, with whom Tasia and her younger brother Jeremiah lived with, died suddenly from complications of kidney failure.

“The papers were signed, but I wasn’t able to go through with it,” Tasia said. “I had to make sure he was OK.”

Tasia, 20 at the time, became her brother’s guardian.

While Tracy Crawford’s passing in June 2023 ended Tasia’s goal of joining the Navy, it didn’t end her goal of a bright future for herself and Jeramiah.

For that, she credits Florida's private school scholarships managed by Step Up For Students.

The scholarships enabled Tasia, now 22, and Jeremiah to attend Academy Prep Center of St. Petersburg for middle school and allowed Jeremiah, 15, to continue his private school education at Admiral Farragut Academy in St. Petersburg, where he is a sophomore this year.

“(The scholarship) gave us the opportunity to go to a school that we probably wouldn't be able to go to,” Tasia said. “It gave us the opportunity to expand our knowledge so good things can come into our lives.”

Tasia is studying to become a phlebotomist and works as a teacher at the Academy for Love and Learning in St. Petersburg.

Jeremiah would like to attend the United States Air Force Academy and work in cybersecurity.

The two, who share an apartment in St. Petersburg, have goals and are working toward them with a determination forged by Tracy Crawford, their grandmother, and reinforced by their years at Academy Prep.

“They don’t let you give up,” Tasia said when asked what she liked about attending Academy Prep. “Even if you had issues, they never let you give up.”

Could you blame them if they did?

Tasia was 8 and Jermiah was three weeks old when their mom died. Staci Crawford was only 34 when she suffered a heart attack. That left the children in the care of their grandmother, whose failing health forced Tasia to find work as a counselor at the Police Athletic League when she was 14.

“I had to help out with the bills,” she said. “By the time I was 16, I was cooking, washing everybody's clothes, helping my grandmother out the best I could.”

So, when asked what it’s like to have his sister as his guardian, Jeremiah said, “It’s kind of all I’ve known.”

Tracy wanted Tasia to attend a school that would challenge her academically and offer a safe environment. That’s why she used the private school scholarship to send her to Academy Prep.

At first, Tasia said, it wasn’t a good match. She was not a fan of the school’s long days (7 a.m. to 5 p.m.) or the fact that she had to wear a uniform.

“It took her a while to buy in, and then once she did, she was a high-achiever, and she set the tone for the other kids,” said Lacey Nash Miller, Academy Prep’s executive director of advancement.

For that, Tracy gets a big assist.

“She made sure my grades were straight, my attitude was straight,” Tasia said. “By seventh grade, it all came together.”

For high school, Tasia attended her assigned school because it offered a BETA (Business, Entrepreneurial, Technology Academy) program that interested her.

Jeremiah attended his assigned elementary school, but Tracy wasn’t a fan of his assigned middle school.

“It wasn’t up to her standards,” Tasia said. “She wanted to challenge him.”

So, like his sister, Jeremiah headed crosstown to Academy Prep, where he said he benefited from the school’s academic environment and the self-discipline the teachers try to instill in the students.

Jeremiah said he became more extroverted during his years at Academy Prep.

“I was naturally a quiet person. I didn’t talk much,” he said. “Now, I talk to people. I try to start conversations.”

He also credited his teachers, specifically Zack Brockett, a science teacher, for guiding him toward being a young adult.

“He pushed us to grow up, so that we can go into high school as mature students,” Jeremiah said.

His teachers at Academy Prep describe Jeremiah as a quiet student who completed his assignments on time, helped out around campus, and amazed them with his drawing ability.

“Jeremiah is very self-driven,” Britanny Dillard, Academy Prep’s assistant head of school, said. “He’s one of those people that you kind of underestimate because he's so quiet that you don't even truly realize the talents that he actually has. He’s not the first to raise his hand, but he knows the answer.”

Jeremiah was a member of the school’s track team. He threw the shot put and discus. At graduation, Jeremiah received the Priscilla E. Frederick Foundation, worth $1,500 toward the balance of his freshman year tuition at Admiral Farragut. Frederick is a former Olympic high jumper who competed for Antigua and Barbuda in the 2016 Summer Games. Her foundation awards scholarships and grants to students raised in single-parent households. Jeremiah was the first Academy Prep student to earn that scholarship.

He is a soft-spoken, unassuming young man with a growing vinyl record collection and an interest in graphic novels and comic books. He will participate in track and field this year and will take an aviation class, which he feels will benefit him when he gets to the Air Force Academy.

Jeremiah spends his high school volunteer hours at Academy Prep. He helps grade papers, organize classrooms, and move supplies around campus.

Jeremiah and Tasia are spoken highly of at Academy Prep. Both Dillard and Nash Miller said they were “heartbroken” when they learned of Tracy’s death, and both admitted they were worried for the future of the siblings.

“They only had each other, and I think it speaks highly of Tasia that she was willing to accept that role,” Dillard said.

Said Nash Miller: “The news that her grandmother passed just gutted me. She had all these plans, and she just cancelled them to be her brother’s primary caregiver. What a superhero to put her brother’s needs ahead of her own.”

If anyone needs more proof that the future of education is in Florida, take a look at the winners of Thursday night’s Yass Prize Awards. Six Florida-based providers, including two finalists who took home $250,000 each, were among the 23 honored for their innovative and scalable programs.

One of the finalists, Pepin Academies, is a charter school network with three campuses in the Tampa Bay area. It offers students with learning disabilities in grades three through 12 an inclusive environment where academics and essential therapies happen together in real time.

“I have always rejected the principle that we have to think outside the box for students with disabilities,” said Jeff Skowronek, executive director of the 25-year-old network. “A truly inclusive society is one that understands how to make the box bigger.”

Pepin stands out for its small class sizes, ESE-certified teachers, and onsite specialists, including mental health counselors, social workers, speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, ESE specialists, and registered nurses, according to Yass Prize offices. This ensures their children receive individualized attention throughout the entire school day. In addition to its schools, Pepin operates a transition program for young adults ages 18-22.

According to Yass Prize officials, the award empowers Pepin Academies to serve students earlier, expand their transition program, and bring their therapeutic model to more families seeking a school that understands and supports exceptional learners at every stage.

The other finalist, WonderHere, is a network of child-centered microschools that focus on play-driven, project-based learning and personalized education to let children learn at their own pace.

“We are so excited and grateful to the Yass family and the Center for Education Reform for selecting WonderHere as a finalist,” said Tiffany Thenor, who opened the first campus in Lakeland after spending seven years in the public education system. She opened WonderHere to challenge the norms of schooling and prove that learning can be more joyful, flexible, and deeply human. A second location opened later in Anderson, South Carolina, and a third is planned for Davenport, Florida, near the original location.

Thenor said the prize money will help her find a permanent location for the Davenport campus and create more space for families to experience the “project-based, family-centered, wonder-filled learning environment” that WonderHere offers.

The following Florida providers were named semi-finalists and received $100,000 each: Archimedean Schools of Miami; Space Florida, Merritt Island; Ecclesial Schools, Oviedo; and GuidEd, a Tampa-based bilingual program that provides free, unbiased information about educational choices to help families determine the best fit for their children.

“GuidEd looks forward to using our Yass award money to enhance our call center capabilities to provide more sophisticated and personalized 1:1 support for families and to reach new families who may be entering the education freedom marketplace for the first time," said Kelly Garcia, who founded GuidEd with her brother-in-law, Garrett Garcia.

The Yass Prize, often called the “Pulitzer of Education Innovation,” began in 2021 to recognize innovative educators who delivered top-tier learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Philanthropists and education choice champions Jeff and Janine Yass established the award and continue to fund the program.

The top winner takes home a $1 million prize. This year, it went to Chesterton Schools Network, a national network of classical high schools rooted in Catholic values. Though headquartered in Minnesota, Chesterton has Florida schools in Orlando, Pensacola, Sarasota, and Vero Beach, with a fifth set to open in 2027 in Melbourne. Primer Microschools, which began in Florida and has expanded to other states, won the grand prize in 2024. That year, it announced the establishment of Primer Fellowship, which provides paid training for edupreneurs seeking to open Primer Microschools in their communities.

When Florida lawmakers debated HB 1 earlier this year, the discussion largely focused on how the legislation would dramatically expand education choice through universal eligibility and flexible spending options for families.

Another part of the bill inspired far less discussion but got the attention of school district leaders across the state: a review of public school regulations.

By Nov. 1, the state Board of Education must develop and recommend “potential repeals and revisions” to the state’s education code “to reduce regulation of public schools.”

“This is a great step towards keeping our public schools competitive” in an era of expanded options, said Bill Montford, a former Democratic state Senator from North Florida who heads the Florida Association of District School Superintendents.

“Traditional, neighborhood public schools have been, and will continue to be, the backbone of our K12 education system,” he

Bill Montford

said. “We want our schools to be the first choice for parents, not the default choice, and to do that we need to reduce some of the outdated, unnecessary, and quite frankly, burdensome regulations that public schools have to abide by,”

Before they propose any changes, state board members must consider feedback from a diverse group that includes teachers, superintendents, administrators, school boards, public and private post-secondary institutions and home educators.

To fulfill that requirement, board members set up a survey link that will accept suggestions through today. A group of superintendents submitted a recommendation list that covers topics that include construction costs, budgets, enrollment, school choice, instructional delivery and accountability. Their pitches included proposals to:

"We’d like for them to recognize all parental choice equally and give school districts the same flexibility and opportunity to innovate provided to other publicly funded options,” said Brian Moore, general counsel for the superintendents association that Montford leads. He added that the superintendents would like to see more cooperation between school districts and the Department of Education.

This effort isn’t the first the state has made to provide school districts with relief from what they see as burdensome regulations. But to some leaders the process seems more like a game of Whac-A-Mole, with new regulations soon replacing the ones that get repealed.

Ten years ago, Gov. Rick Scott signed SB 1096, which repealed some regulations based on the recommendations of a group of superintendents, including Montford. The bill repealed a requirement approved in 2010 that all public schools and universities gather and report statistics showing how much material each had recycled during the year. It also ended a 2002 requirement that schools submit plans for teaching foreign languages to kindergarteners.

Other efforts to ease the regulatory burden have targeted schools that meet certain conditions. Since 2017, schools with strong test scores and consistently high letter grades could be qualified as “Schools of Excellence,” which grants their leaders more flexibility.

Moore said he hopes things work out this time around, but said the key is allowing changes to apply across the board, not to certain schools or districts, and to carefully consider future regulations and their potential effects.

Christina Sheffield’s son, Graham, was soaring ahead of classmates. She wanted a learning environment that challenged him, so she created one herself.

She pulled him out of a private school and created a customized education plan. Using her know-how as a certified elementary virtual school teacher, she enrolled him in a hybrid homeschool co-op and designed projects to enhance the curriculum his former private school as using.

But there was a missing piece in her son's custom education plan: Their neighborhood public school.

That changed when the Tampa Bay area mom received the results of her son’s test for academic giftedness. Now officially identified, Graham, like other gifted homeschoolers, was able to access services offered by his local school district. He started going to a weekly gifted class at his zoned elementary school.

“It was his favorite day of the week,” Sheffield recalled. “After I picked him up on the first day, he said, ‘Mom, I finally feel like I fit in.’ That made my mom’s heart happy.”

Other students in similar circumstances might not be so lucky. Florida law allows homeschoolers to enroll in dual enrollment classes that lead to college credit, free of charge. Students participating in the state's growing array of educational choice options have access to extracurriculars at their local public schools under the state's "Tim Tebow law." But that same guaranteed access does not extend to math class.

Districts can offer homeschoolers access to career and technical courses, or services for exceptional students, included gifted programming for students like Graham. And a new law allows districts to receive proportional funding for any student who chooses to enroll part-time while participating in other educational options.

But they are not required to offer this opportunity.

A new analysis by the advocacy group yes.everykid. evaluated policies in all 50 states and found that states vary widely in policies that grant students access to their local public schools, regardless of where they live or whether they want to enroll full-time.

Florida's policies place it in the top 10 among states, but it has not yet guaranteed that every student has the right to access public schools on their terms.

Among the findings:

Florida tied with Alaska for ninth place when it came to allowing nonpublic and homeschool students access to public schools. Idaho, which met every criterion used in the rankings, was No. 1, followed by Iowa and Minnesota, which tied for second place.

Though HB 1 codified the option for Florida public school districts to offer part-time enrollment options and receive prorated state funding, it left the decision whether to participate up to the individual districts.

Districts may be reluctant to embrace this new flexibility, and some state policies make this understandable. For example, state class size limits may add to the staffing headaches for districts hoping to accommodate students who enroll part-time.

The new law also creates a process for districts to identify regulatory barriers that are preventing them from responding to the needs of students and families.

For decades, some districts have resisted the oncoming tsunami of new education options. Others have chosen to ride it, and now have new flexibility at their disposal. The question is whether they will capitalize on that flexibility to meet the needs of their students.

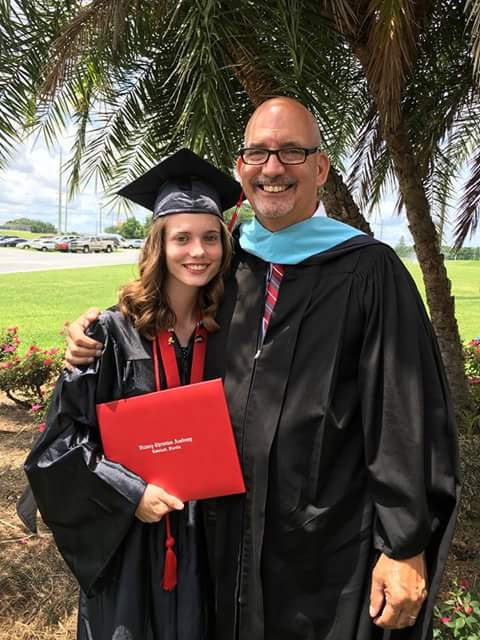

Ashley Elliott of Florida and her principal after her high school graduation. Elliott now serves as coordinator of the Future Leaders Program at the American Federation for Children.

Editor's note: This commentary by Mark LeBlond, policy director of EdChoice, was originally published in the Washington Examiner.

Ashley Elliott was one of the “hard cases.”

Born addicted to drugs and raised by her single grandmother, life was hard for Ashley. She struggled in school — until 10th grade. After years of fighting, bullying, and poor grades, Ashley found refuge in Lakeland, Florida , when a private Christian school admitted her on a tax credit scholarship. There she found teachers who cared about her, who believed in her.

In turn, Ashley began to believe in herself. Ashley thrived, graduating high school, then college, and embarking upon adulthood as an education advocate.

A thousand miles to the north, Pennsylvania policymakers are grappling with a related policy problem. How can the government guarantee a thorough and efficient education to all students, regardless of their background, socio-economic status, or zip code?

In a case dating back to 2014, William Penn School District v. Pennsylvania Department of Education, the plaintiffs argued the state fell short of its constitutional guarantee, and further, that an overhaul of the school funding system is the only solution. After years of wrangling over the role of money in Pennsylvania public education, the courts finally ruled earlier this year.

The Commonwealth Court ruled that Pennsylvania’s present education funding model is broken, yet stopped short of prescribing a fix, instead leaving solutions to the legislature and governor. In her opinion, Judge Renee Jubelirer emphasized that reform does not have “to be entirely financial ... The options for reform are virtually limitless. The only requirement, that imposed by the Constitution, is that every student receives a meaningful opportunity to succeed academically, socially, and civically, which requires that all students have access to a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary system of public education.”

To continue reading, go here.

Among Ilen Perez-Valdez’ many accolades: National Honor Society member, Immaculate-LaSalle’s Spanish Honors Society president, Science Honors Society vice president, and English Honors Society treasurer.

MIAMI – Nery Perez-Valdes wanted to become a doctor, but life got in the way.

She fled Cuba for Miami with her mom when she was 11 and found herself working at 14 to help pay the bills. Nery would become a single mom and for a long stretch worked two jobs to keep the lights on and food on the table.

Nery always wanted a private school education for her daughter, Ilen, and a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship made possible by corporate donations to Step Up For Students allowed that to happen.

“I was a single mom since I was three months pregnant, and when I’m saying, ‘single mom,’ I’m telling you ‘single mom.’ No child support. No help. No nothing. Period. The end,” Nery said. “Thanks to Step Up For Students, Ilen was able to get the education I wanted for her.”

Ilen has made the most of that opportunity – and then some.

She graduated this spring near the top of her class at Immaculate-LaSalle High School, a prestigious Catholic school in Miami. She has a scholarship to the University of Miami and plans to major in neuroscience and double minor in business administration management and Spanish. Her goal is to attend medical school and become a pediatric oncologist.

“My mother never received a college education. She was barely able to graduate high school. All she has done since she got (to the United States) is work, work, work,” Ilen said. “She came here looking for the American dream. I feel like if I succeed, she can live out her American dream through me.”

Ilen has received a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship since kindergarten. She said she’s grateful for the opportunity to receive a quality education – first at Saint Agatha Catholic School, and then at Immaculata-LaSalle.

“It was really difficult to make ends meet when I was younger, so I wouldn’t have been able to attend a private school where I received such an excellent education,” she said.

To continue reading, click here.

On this episode, reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie talks with Sue Luther of Largo, Florida, a former private school teacher and single parent of two military-dependent sons. Both boys have received state K-12 scholarships over the years.

Her older son, Alexander, 15, was diagnosed at age 2 with severe autism spectrum disorder and currently receives the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities. His younger brother, Miles, 13, attends a charter school. The different uses of education choice earn Luther and her kids the title “multiple choice family.”

Luther discusses how she felt after Alexander, at the time a third grader, qualified for what was then the Gardiner Scholarship and how it helped her design a customized plan at home for him and later allowed her to send him to a private school for students with autism.

As a sibling, Miles qualified for what was then an income-based scholarship. Luther used it to pay private school tuition until Miles began attending a charter school, which, though privately run, is publicly funded. Florida law classifies charter schools as public schools.

Luther loved what the private specialty school offered Alexander, but as a single parent, she will not be able to cover the difference between tuition and what the scholarship pays next year. So, she plans to use scholarship for a customized home-based program.

“It helps you have accessibility to so many resources, and it covers so many of the expenses that it takes to homeschool your kid. With technology nowadays, you have to have laptops and computers and cell phones, or tablets of some kind to help them. And it really helps to cover those things so that you feel like you're still giving your child the best opportunity to learn, just like their peers.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

Archdiocese of Miami Virtual School, owned and operated by the Archdiocese of Miami, offers full- and part-time enrollment, introducing students to Catholic virtues and principles while enhancing learning for participants across the country.

When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed HB 1 into law, he praised it as “the largest expansion of education choice not only in this state but in the history of these United States.” During committee hearings, lawmakers called it “transformational.”

The sweeping legislation extended eligibility for the Sunshine State’s 20-year-old school choice program to every student regardless of income. It also gave parents more control over their children’s education by converting traditional scholarships to education savings accounts.

The accounts, called ESAs, allow funds to be spent on pre-approved uses such as curriculum, digital materials, and tutoring programs in addition to private school tuition and fees.

But despite the greater opportunities for customization, one thing was not included: religious virtual schools. Under the new law, students may use funds to attend non-sectarian virtual schools, such as Florida Virtual School, and traditional in-person religious schools, but not a combination of the two.

That language means that schools such as Archdiocese of Miami Virtual Catholic School and Families of Faith Christian Academy International, which offers a private virtual school option, are excluded from participating in the state’s K-12 education choice scholarship programs. However, families who are using personalized education plans under HB 1 are allowed to use ESA funds to buy curriculum from ADOM Virtual Catholic School, even though they can't use the money to enroll at the school.

The Lakeland-based school is working on passing inspections for a campus on property owned by Epic Church, according to its website. Students who attend the in-person campus full time will be able to use scholarships. Before the pandemic, the school offered a blend of traditional and home-based instruction for homeschool families.

However, when Covid-19 made online education more popular, the school focused more on its virtual offerings.

Jim Lawson, the administrator at Families of Faith, hopes that closing the loophole will be on the lawmakers’ list when the 2024 session begins.

“With all the good that is included in HB 1, which we support, the Florida Legislature has continued to limit a wide range of high-quality educational options,” said Lawson, administrator for Families of Faith, who co-founded the school in 1994 with several other homeschool families.

“Parents can choose a high-quality campus-based program that aligns with the academic needs of their students while not conflicting with their faith. But they are not given the same choice to choose a high-quality accredited virtual program for a faith-based private school. The foundational principle of school choice is to have the same menu of options that families who choose the public school system, which includes FLVS, available to them from the private sector.”

Jim Rigg, superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese of Miami, which has a virtual Catholic school that offers full- and part-time programs, has a similar perspective.

“We favor efforts that maximize the ability of families to choose the school that best fits their child’s needs,” Rigg said. “This would include faith-based virtual schools, such as the ADOM Virtual School used by hundreds of students throughout Florida and across the world.”

Some say the language puts HB 1 in conflict with the First Amendment’s free exercise clause cited in recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions Espinoza v. Montana and Carson v. Makin, which forbade Maine and other states from discriminating against religious schools in state education choice scholarship programs.

In Espinoza, the high court ruled that a state “need not subsidize private education” but that once it “decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

In Carson, the high court ruled that states could not ban faith-based schools from participating in state scholarship programs because the schools engage in religious activities. The case involved town tuition programs offered in some Northeastern states that offer students in rural areas funding to attend private schools where there are no district high schools.

“Likewise, a state need not subsidize families choosing virtual learning, but once it decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some virtual learning providers solely because they are religious,” Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, wrote in a recent analysis.

Shawn Peterson, president of Catholic Education Partners, a national organization that promotes greater access to Catholic education, agreed, saying that although he applauds the passage of HB 1 and welcomes the wealth of options it offers, he hopes to see some changes.

“We hope that lawmakers om the Sunshine State will fix the legislation to ensure that all providers to ensure that all providers can participate in the new program,” he said.

Bedrick urged lawmakers to tweak the bill by inserting language clarifying that notwithstanding any other provision in Florida statute, families using education savings accounts may choose virtual providers that offer religious or secular instruction, and that the language should specify that virtual learning counts toward regular attendance regardless of whether students are enrolled in brick-and-mortar schools.

“Florida has an opportunity to reclaim its mantle as the leading state for education freedom and choice,” Bedrick wrote. “With just a few small but important tweaks, the Sunshine State could adopt a policy on universal education choice that will be a shining example for other states to follow.

Any tweaks will have to wait until the 2024 legislative session, which begins Jan. 9.

When the doors of the former Warrington Middle School open in August, students will enter a new School of Hope.

When the doors of the former Warrington Middle School open in August, students will enter a new School of Hope.

Members of the State Board of Education unanimously approved Renaissance Charter School’s application to be a School of Hope operator in Escambia County, the westernmost county of the Florida Panhandle. Renaissance, a non-profit organization, is managed by Charter Schools USA, a for-profit company based in Fort Lauderdale that serves 100 charter schools across the United States.

The approval came a week after the Escambia County School Board approved a contract with Charter Schools USA and Renaissance to take over operations at Warrington Middle School, which has struggled academically for more than a decade and has not received a state grade higher than a D during that time.

The designation, allowed by a law passed in 2017, includes several conditions that allow charter operators to be named Schools of Hope. Those include charter schools that are approved to take over struggling district schools that are in the state turnaround process. It also gives the charter operators access to additional state funding.

The most recent designation in this category was granted to Somerset Academy, Inc., which took over the Jefferson County School District in 2017 after the district’s long string of failing state grades. After its five-year contract ended, Somerset turned the schools back over to district officials.

“This is not just a name; it’s just not a designation with bragging rights,” said Adam Emerson executive director of the Florida department of Education’s Office of Independent Education and Parental Choice. “It also does come with some significant resources, startup resources, that can get help get them off the ground for a successful start this fall because the first day of school is only a few months away.”

Emerson said the state education department would take an active role in helping Renaissance Charter School as it reopens the former Warrington Middle campus and will provide updates at each monthly state Board of Education meeting.

“This has been the bane of our existence for quite some time,” board member Monesia Brown said. She pointed out that the district’s messaging during the contract negotiation process had been primarily negative and asked that future communications from the state reassure parents that “this is an investment to make sure their children get the quality of education they deserve.”

The approval of the contract between the Escambia County School District and Charter Schools USA marked the end of two months of tense negotiations over the school’s future enrollment policies, fees and long-term lease issues.

District leaders also faced the wrath of state officials and board members who criticized them for failing to make progress in reaching an agreement with the charter organization.

In a surprise move shortly after voting to approve the contract, the Escambia County School Board fired the superintendent.

Emerson said now that the contract has been signed, the community is coming together, and that a recent meeting “struck a collaborative tone to move forward.”

David Facey, who attends a private school in Florida using a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, cheers for the Tampa Bay Lightning at a game in Tampa during the 2022-23 hockey season.

PINELLAS PARK – David Facey remembers sitting in his Language Arts class last year hoping for salvation. Hoping someone would pull the fire alarm. Drastic, yes, but anything to bring class to an end.

The other students were nearly finished with their writing assignment. David had written only three words.

His teacher noticed. She wasn’t happy.

“David, what’s wrong with you?” she asked. “You need to concentrate.”

David wanted to scream.

It’s not a lack of focus. It’s dysgraphia, a neurological disorder that affects his ability to write. David can’t write within the lines. He can’t properly space letters. It took him nearly the entire class to write those three words. His hand cramped. He had a headache. He could no longer remember what he was writing about.

The topic was the ocean. David can talk for hours about the ocean. He just can’t write about it. That led to a confrontation with the teacher, a trip to the principal’s office, and a phone call to David’s mom.

David’s biological mother used drugs throughout the pregnancy, said Betty Facey, who along with her husband, Arlen, adopted David when he was 3. David was born addicted to those drugs. As a result, he has dysgraphia and dyscalculia, another neurological disorders where he struggles with numbers and math. He has atypical cerebral palsy, which affects his core strength and fine motor skills. He struggles with anger management.

“His are more hidden disabilities,” Betty said.

David, 14, didn’t have a problem in school until the Faceys moved from Michigan to Pinellas Park in 2021. Betty learned the teachers at his assigned school were not following his individual education plan. He couldn’t understand assignments. He couldn’t complete them. He couldn’t keep up with his classmates.

And when confronted by his teachers, he couldn’t control his anger.

“I would act all crazy and stuff,” David said.

With the help of an education choice scholarship, Betty enrolled David at Learning Independence For Tomorrow (LiFT) Academy in Seminole. LiFT is a private K-12 school that serves neurodiverse students.

“I would say if Florida didn’t have this (education choice) option, he would be stuck in (his assigned school) school,” Betty said. “He’d have to put up with the stuff they were dishing out. … He would hate school. He would probably not have a chance to graduate.

“To me, to be able to get him in a place like LiFT, which really is the perfect place for him, is sort of like a miracle.”

To continue reading, click here.