A Tampa Bay area morning TV show kicked off National School Choice Week by highlighting a family who benefits from a state K-12 scholarship.

Arielle Frett appeared on Fox 13’s “Good Day Tampa Bay” program on Monday with her son, AnyJah, a ninth grader at The Way Christian Academy in Tampa. She said she moved to Florida from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, in 2017 to find better educational opportunities for AnyJah, who has severe autism.

“No teachers were able to work with him on his level,” Frett told Fox 13 reporter Heather Healy. “Most of his learning in English and math are on fifth and sixth grade levels now.”

A U.S. military veteran and single mother of two, Frett said she would not have been able to afford a private school for her son without the scholarship.

She said AnyJah, who receives the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities, is “loved, protected, and thriving” at his school, where class sizes of 10 to 12 students allow for more individual attention. He can also receive his therapies during school.

The segment also featured information about Florida’s robust education choice options. Those include traditional public schools, district magnet schools, charter schools, private schools, microschools, homeschools, virtual schools, and customized education programs that allow parents to mix and match.

“We’ve gone from education and funding through the system to now empowering families by putting the money in their hands and allowing them to make the most appropriate educational decisions for families,” said Keith Jacobs, director of provider development at Step Up For Students, which administers most of the state’s education choice scholarships.

Jacobs has spent the past year working with school districts to provide individual courses to scholarship families whose students do not attend public or private school full time, paid for with scholarship funds. About 70% of Florida school districts are participating.

The scholarship application season for the 2026-27 school year begins Feb. 1. Visit Step Up For Students to learn more and apply.

At Master’s Academy in Vero Beach, Florida, the volleyball program seeks to provide a competitive and successful opportunity that points players to Christ and builds the character of Christ within each student athlete.

One of several bills that would let charter school students play sports and participate in extra-curricular activities at willing private schools has cleared the Florida Legislature and awaits Gov. Ron DeSantis’s signature.

In a display of bipartisanship, all 116 of the House members who were present voted to approve SB 190, which was substituted for its companion, HB 225.

Both bills would allow charter school students to play on private school sports teams and participate in private school extra-curricular activities fi a private school agrees. Current law already allows homeschooled students to do this, and these bills would extend the same provisions to those who attend charter schools and Florida Virtual School.

The vote came nearly a month after the Florida Senate gave final approval in a 38-0 vote.

“We are just absolutely thrilled,” said Wayne Smith, head of school at Master’s Academy, a small private Christian school in Vero Beach that served as the inspiration for the bill. He said the outcome could be a good civics lesson for his students, who were demoralized when the Sunshine State Athletic Association disciplined the school for letting students at a nearby charter school to play on its varsity football team.

Under current law, if a specific program isn’t available at a charter school, the only option for those students is to sign up for it at their zoned district schools. The proposed legislation would let charter students choose between the district school and or a nearby private school through a special agreement.

However, the arrangement at Master’s Academy had been going on for years without controversy, based on an interpretation of the law that allowed the homeschoolers to play at private schools.

Last year, someone complained, and the Sunshine State Athletic Association forced the charter school students off the team in the middle of the season and stripped Master’s Academies of its victories up to that point.

Smith said the decision left the students heartbroken but motivated.

Members of school tennis and baseball teams stepped up to fill the vacancies on the football team. Despite the disciplinary action, the school ended up winning the championship.

News about the controversy got the attention of the community’s state senator. Sen. Erin Grall, a Republican whose district includes Vero Beach, responded by sponsoring SB 190.

“The parent makes the decision not to send their child to the public school they’re zoned for and instead chooses to send their child to a charter school,” she said during a committee meeting on the bill. “This lines up the homeschooling statute with the charter school statute … to fix it and make it more clear.”

After years of failing grades, Warrington Middle School in Escambia County, Florida, received a D from the Florida Department of Education for the 2021-22 school year, leading the state Department of Education to issue an ultimatum to convert Warrington into a charter school.

Get it done. Now.

That was the firm directive that the Florida Board of Education gave Wednesday to Escambia County School District leaders who have yet to finalize a deal with a charter school company to take over struggling Warrington Middle School.

“I’m trying to contain the level of frustration that I have right now,” said Education Commissioner Manny Diaz Jr. “This school has been failing students for more than a decade, and it’s inexcusable that we’re still having adult conversations and not focusing on students.”

His comments followed an update showing that despite Warrington receiving D grades from the state since 2012, the Escambia County School District still has not finalized an agreement with Charter Schools USA to assume operations in 2023-24.

The state board said the school must be closed or turned over to a charter school partner if it did not receive at least a C grade. After a pandemic hiatus in grading, Warrington received a final grade of D in 2022. The state board then ordered the school closed or turned over to a charter for the 2023-24 school year.

District officials began negotiating in November with Charter Schools USA, which serves 75,000 students in five states. The 26-year-old charter school operator was the only organization to express interest in taking over the Title 1 school, where 80% to 90% of its approximately 600 students live below the federal poverty line.

The parties appeared to be headed toward a May 1 deadline to forge an agreement. However, negotiations hit a snag when district leaders said at an April 13 school board meeting that Charter Schools USA had sent a list of conditions for it to make a long-term commitment to the school.

Terms included a 15-year year contract between the district and Charter Schools USA and a 30-year contract with Charter Schools USA for control of the facility, with the charter organization paying the district $1 per year.

Additionally, new grade levels would be offered each year for the first four years under their control. Some of the grade levels would be zoned for the children living in the Warrington area, while others would be open to all students in the county. By the 2026-27 school year, Warrington would be a choice school for grades K-10, with no zoning.

School Board members expressed concern that a conversion to open enrollment would leave area students without a zoned neighborhood school, requiring them to be bused elsewhere.

Members also expressed concerns that handing over facility control for 30 years could put a future school board in a challenging position, especially because district school construction must meet state hurricane shelter standards. They further said they didn’t want to saddle a future board with debt if the charter company decides to leave.

Yet another concern was that Charter Schools USA had not submitted an application spelling out details of school operations.

Escambia Chairman Paul Fetsko assured state board members that the district is not anti-charter and sponsors nine “really good” charter schools.

“Our students are our number one priority,” he said. “We want them to learn wherever they can best be served. We want to work with Charter Schools USA, but the last-minute non-negotiables have been extremely difficult.”

However, Escambia school leaders garnered no sympathy from state officials, who called the concerns “excuses.”

Diaz said that as a state lawmaker, he included language in a bill that gave school districts flexibility from shelter requirements if the community already had enough shelter space so that should not be a concern.

State board Vice Chairman Ryan Petty criticized the district for expecting an application from Charter Schools USA, which it approved as a partner in the fall.

“So, you picked them and now you’re asking them to jump through bureaucratic hoops of an application? What’s the point?”

Petty said that during a tour of Warrington, he peeked into an eighth-grade classroom where algebra books sat on a shelf while a teacher’s lesson focused on basic arithmetic.

“You’ve been failing these students for over a decade,” he said.

Board member Esther Byrd said given the school’s poor performance, “Can you currently say to the parents of the children at Warrington Middle School that they’re succeeding, and they’re being taught because these numbers don’t say that. I don’t see how another option can be worse than what we have right now.

“This board has expressed a balance of urgency and grace, and I just want to say that as far as I’m concerned, we’re done with grace. So, we’ve got to get this done.”

Smith said the district is working hard to strike a deal.

“We’re not arguing; we’re not making excuses. What we’re saying is we need help getting this agreement across the finish line.”

State Board Chairman Ben Gibson called the repeated failure at Warrington “a bad dream” and said the district has little choice but to accept the terms.

“We’ve been desperate to get a charter operator in there,” he said. “Compromise is really the only option that we have. You don’t have a lot of negotiating power here.”

Charter Schools USA officials did not attend the state board meeting. However, Eddie Ruiz, the organization’s state superintendent, issued the following statement Wednesday to reimaginED:

“We were honored to be asked by the Escambia County School Board for help to turn around Warrington Middle School, which has been failing for decades. When we evaluated the significant problems at the school, we came up with a plan that points to the greatest opportunity for a successful turnaround.

“Unfortunately, the board found the terms to be unacceptable. We know what it takes to turn around failing schools, and we can implement those changes if we are given the ability to make them. One thing that is critical in this process is the cooperation and support of the authorizer, which we clearly do not have at this point.

“We believe all students deserve access to a high- quality education. At CSUSA, we have a relentless commitment to student greatness in school and in life.”

The Master’s Academy football program seeks to improve players’ God-given talents, teach them how to be team players, and learn valuable life skills through the sport of football.

While transformational bills to expand education choice eligibility have taken center stage during the Florida legislative session, other measures that would affect those already participating in choice programs also are under consideration.

Some may not make it to the finish line before the end of the eight-week session, but at least one measure is already on track for approval.

Companion bills HB 225 and SB 190 would allow charter school students to play on private school sports teams and participate in private school extra-curricular activities. Current law already allows homeschooled students to do this, and these bills would extend the same provisions to those who attend charter schools.

A recently approved amendment in the House Choice and Innovation Subcommittee also extended the provision to students enrolled in Florida Virtual School.

Under current law, if a specific program isn’t available at a charter school, the only option for those students is to sign up for it at their zoned district schools. The proposed legislation would let charter students choose between the district school and or a nearby private school through a special agreement.

SB 190 is set to be heard on the Senate floor starting at 1:30 p.m. Thursday; HB 225 won final approval in that chamber on Friday and was sent to the Senate, where it is now in the Senate Rules Committee.

The bills were inspired by an incident last year in Vero Beach, in which a group of charter school students were forced off the Master’s Academy varsity football team in the middle of the season of their senior year after someone complained.

The arrangement had been going on for years based on an interpretation of the law allowing homeschoolers to play for private schools. The Sunshine State Athletic Conference also overturned all of Master’s Academy’s victories at that point, though the private school ended up winning the championship.

“We were heartbroken,” Wayne Smith, the head of schools at Master’s Academy, told Florida Politics in January. “It hurt us, but more than that, it hurt these charter school boys who had nowhere else to play, nowhere else to go, and suddenly they were without a team — kicked off a winning team, nonetheless.”

Smith, whose school has 45 high school students, said the charter students would be unlikely to make the team at their district high schools, “So, they come to us.”

State Sen. Erin Grall, a Republican whose district includes Vero Beach, sponsored SB 190 and said the legislation would create consistency among all students who participate in different forms of education choice.

“The parent makes the decision not to send their child to the public school they’re zoned for and instead chooses to send their child to a charter school,” she said. “This lines up the homeschooling statute with the charter school statute … to fix it and make it more clear.”

When Melissa Ley’s daughters, Allison and Abigail, now attending St. Petersburg Collegiate STEM High School and St. Petersburg College, respectively, were younger, Ley enrolled them in Florida Cyber Charter Academy, where she now serves on the board.

Melissa Ley left her job as a teacher at a public school to let her daughters learn at home after determining the public schools they attended were not the best fit for them. At the time, Ley’s family didn’t qualify for an education choice scholarship, so she enrolled the girls at a district virtual school.

Things went well until district leaders decided to convert from live lessons to an asynchronous education model – one in which educational activities, discussions and assignments engage students in learning at their own pace, on their own time.

Ley moved her children to Florida Cyber Charter Academy, where she serves on the Florida Cyber Charter Academy board. She has become a fixture at legislative committee meetings and advocates for education choice by writing letters to the editor at the South Florida Sun Sentinel and other newspapers.

Ley shared her story with reimaginED to encourage other education choice advocates looking for the best educational fit for children nationwide. Answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q. Please tell me a little about yourself: What was your own K-12 education like? Did you always want to be a teacher or was it something that you felt called to later, during high school or college?

A. I was born and raised in Florida and attended my zoned schools. I knew in high school I wanted to be a teacher. I worked full time in college and attended college while working. Eventually I decided that since I was already making more as an administrative assistant than I would as a teacher, that I was better off where I was and didn’t finish college.

I worked as a corporate recruiter and trainer for years, and after I had my first child, I started re-evaluating what I really wanted to do, so I left my job and went back to school to get my degree in education.

Q. Please tell me a little about your family. Where do your kids attend school?

My husband of 20 years and I have a 19-year-old daughter, Abigail, who graduated from St. Petersburg Collegiate High School (a charter school) in May of last year with her high school diploma and her associates of arts degree. She is attending St. Petersburg College. My younger daughter, Allison, attends St. Petersburg Collegiate STEM High School. It is a brick-and-mortar charter school that will allow her to graduate with her high school diploma, her associate degree, and two industry certifications. Prior to this, she attended a virtual charter school from kindergarten through eighth grade.

Q. How did you know what learning plan was the best fit for them?

Abigail started in a magnet school and in second grade I started seeing some things that had me questioning whether it was the right fit for her. My daughter started coming home saying she was a terrible reader. She wasn’t. She loved to read and was gifted, but when I asked her teacher why she thought Abigail had this impression, and if she noticed her struggling in small group or during class, the only information she could give me was my daughter’s district test score. She had no running records, no feedback on how she read in class, or during small group instruction, no assessments at all. Just that she failed this one test on this one day, and from it related to my daughter she might not pass the grade.

As a teacher in the district, I knew what was expected of me and the data and instruction happening in my classroom with my own students, and I felt like it wasn’t acceptable that there was no data on my child. She was doing well on her report cards, but when I sat down to do her homework with her, it was obvious that there were some gaps in her learning. I figured it was one year, one teacher. I would work with her to fill in the gaps and it would be okay.

The next year, my younger child was in VPK, reading well above her grade level, and academically excelling, and her teacher suggested she go straight to first grade. But socially, we knew she wasn’t ready to skip a grade. I started researching other options for her. Do I work to pay for a Montessori school, or something that was more flexible and able to accommodate all her needs?

Then a few months into that school year, I decided to homeschool them. When looking into homeschool options, I came across a virtual school, and at the time it was through the district. I fell in love with the curriculum and the ability to school my kids at home and be there and see if there was any remediation or acceleration needed.

Q. What was the reaction when you, a public school teacher, put your children into a non-traditional school?

At first, because we started with a district virtual school, most people didn’t really say much. A few weren’t thrilled that I was “schooling them at home,” but some thought it was amazing. However, when the following year our district virtual school wanted to eliminate the curriculum we were using and the live classes and go to an asynchronous model where a classroom teacher would oversee five virtual school students, we chose to leave and move to a virtual charter school.

Q. Have you always supported education choice and scholarships or was it a view that evolved over the years? If so, what influenced that change?

I have always supported choice, but as with most things, until you personally experience them, you don’t really understand their value. For us, having the option for a virtual charter school was life changing on so many levels. I had no idea the number of people who fought hard for options for students and families or that choosing where you go to school isn’t something that is accessible to everyone.

Living in Florida, we are really privileged with the number of options we have, and I had no idea that this wasn’t the case everywhere. As my own choices were being threatened, I got involved in advocating for choice and realized often those making the decisions to close my school or limit enrollment didn’t understand even the basics of how our school was run.

For example, I spoke to many school board members who had an opinion on the virtual school we attended, but had no idea we had live classes with teachers and students. They kept saying “you mean video recordings.” I also found out they often didn’t know how their decisions impacted those utilizing the school. I also did not realize that those choices are often still threatened and can be taken away.

Q. Please describe your role at Florida Cyber Charter Academy.

I am a board member for Florida Cyber Charter Academy. It is my job to make sure the staff is meeting the needs of the students and families and making sure they are adhering to their charter contract, as well as making sure they uphold all federal, state, and local laws and regulations.

Q. What has inspired your activism when it comes to education choice? Did you start with newspaper letters to the editor or were you engaged in other advocacy as well?

I was asked to be on the board as a parent liaison by one of my daughter’s teachers since I was a very active parent in the school. When I joined the board, I realized that the district was trying to eliminate our charter, and this would leave thousands of kids without the choice that was working best for them, my kids included.

At that time, I started working with the board and the district to try to educate them on how our school really worked and the impact it was having on these families. I served as board chair for a few years, and currently serve as a board member. Then I got involved by writing letters, visiting and speaking with our state and national legislators. I also work closely with other parents to help them learn how to advocate.

Q. What do you think of the education choice expansions in Florida? What about other states, particularly those that have adopted greater spending flexibility in the form of education savings accounts?

Florida has always been a leader in school choice, but with nearly half of Florida’s students utilizing an educational option outside of their zoned brick-and-mortar public school, the Legislature must continue to expand learning options and not roll back options for families. I think we should look to states like Arizona, which has adopted universal ESAs, and to Colorado, which has tons of effective online learning options.

Q. Do you think ESAs would benefit Florida and if so, how?

I do think ESAs will benefit Florida. Many families simply lack the financial resources to pursue other options. Private or homeschooling options are expensive. Other families like ours have made financial sacrifices to shoulder the expense of private school tuition or have given up a parent's income to school at home. If the money follows the student, this opens more options for families and helps alleviate the financial strain on families.

Q. What do you see as the future of education?

I think the future of education can be exciting if we work together to provide options and support to teachers, students and families. The more educated we are as a society about education options, laws, and funding, the stronger we can make opportunities for our children.

Optima Domi, a virtual education provider, will integrate virtual reality into the student experience on a daily basis, bringing the highest quality immersive, classroom-based learning to scholars regardless of their location.

Editor's note: In keeping with our year-end tradition, the team at reimaginED reviewed our work over the past 12 months to find stories and commentaries that represent our best content of 2022. This post from reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie is the sixth in our series. Buie donned a headset and took a virtual journey to learn how an innovative Florida school will use virtual reality to accelerate learning.

“Sorry for the delay in responding to your email,” I told a contact last week. “But I was busy walking on the moon.”

“Sorry for the delay in responding to your email,” I told a contact last week. “But I was busy walking on the moon.”

Of course, that wasn’t literally true. Nor was it true that I literally stood inside the Oval Office, visited Niagara Falls, observed sea life on the ocean floor, and peered out at Florida’s Space Coast from the tip-top of a rocket just before launch.

In actual reality, I was in my teenage son’s game room, experiencing it all from his Oculus Quest II headset.

Yet in virtual reality, I was in those environments and got a glimpse of how they will enhance the learning of students who enroll at Optima Classical Academy a charter school based in Naples, Florida, that uses VR to bring lessons to life for children in grades 3 through 8.

Billed by its founders as “the world’s first virtual reality charter school,” the school is set to open in August.

In half-hour segments punctuated by breaks, students will get to experience the ancient city of Pompeii, top art galleries, the ocean floor, outer space, the White House, and other well-known places via the metaverse.

“People say it’s really hard to describe it unless you’ve experienced it,” said Vince Jordan, who joined the Optima Classical Academy staff about a year ago as its chief technology officer and has been designing environments. He told me this while we sat inside a virtual coffee shop in a city that looked a lot like Chicago.

That’s why I decided to take a virtual tour myself after interviewing the school’s founder, Erika Donalds, an entrepreneur and education choice advocate. A former public school board member, Donalds already had developed a charter school in Naples, which is her hometown.

Besides, I saw the movie “Ready Player One” with my son a few years ago and was curious to see if the real metaverse lived up to the hype.

It did.

After creating a login for the Engage app and choosing an avatar – a slightly enhanced version of my “actual” self – I met Jordan via his avatar in the lecture hall. After virtually shaking my hand and giving me an overview, he whisked me away.

When my screen returned — it goes dark during the transports — I found myself on the launch pad at the Kennedy Space Center. I looked around and found I was standing a few feet from a rocket. According to a tourism website featuring things to do in Orlando and Central Florida, the closest a spectator can get to a launch is about 7 miles. But in the metaverse, not only can you walk around the base of the rocket; you can ascend to the very top to see the actual shuttle.

Jordan explained that I was looking at the Saturn V Rocket, which was used in 1969 during Apollo 11 to transport astronauts to the moon. At 363 feet tall, it’s equivalent to the height of a 36-story building and about 60 feet taller than the Statue of Liberty. It’s hard to believe the spacecraft is such a small part of the rocket, Jordan pointed out.

Then, after a few seconds of darkness, my virtual eyes opened. I was, standing in the Oval Office right next to the Resolute Desk, where numerous presidents worked. The experience was so real I could hear the crackle of wood burning in the fireplace.

Seconds later, I left the Oval Office for the moon, where I stood on its gray, cratered surface. I could see a lunar roving vehicle – a moon buggy – in the distance, one of several that astronauts have been left behind. While there is plenty of moon video to watch, it’s so much more vivid to feel like you’re actually in outer space. It’s also cool to look down at your hands and feet and see them clothed in a space suit.

After walking on the moon, I descended to the ocean floor where I saw a variety of sea life, including a great white shark. I also watched a 3-D video in an auditorium that rivaled an IMAX theater.

For a Star Trek nerd like me, the experience was like being on the holodeck, an environment used for virtual vacations but also for education and training.

For students, especially those of modest means who have not had the opportunity to travel much farther than their back yards, such a learning environment can be especially engaging. It also can be useful for teaching skills through simulations.

For now, Optima Classica Academy is a tuition-free charter school. Donalds chose that route in compliance with Florida law, which limits private schools that accept education scholarships to in-person instruction at brick-and-mortar locations.

However, Donalds has said she would consider converting to a private school model if the law changes to allow for universal education savings accounts, a flexible model that allows parents to customize their child’s education.

Toward the end of the demo, the headset started to feel a bit heavy, which is why the virtual school is limiting sessions to 30 minutes and adding breaks for students to work on assignments.

Jordan, who started his tech career working on large mainframe computers and has seen the industry evolve, says that will be temporary as newer headgear will be lighter and eventually look like eyeglasses.

“And if Elon Musk has his way, it could someday be in your brain,” he said.

Which sounds a little scary, unless it means I get a free trip to a vacation destination to some place quiet – like the moon.

Imagine School at Broward is a tuition-free public charter school in Coral Springs, Florida, one of 712 charter schools in the state serving about 360,000 students. Imagine Schools is a national non-profit network of 51 schools in seven states and the District of Columbia.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Amber M. Northern, senior vice president for research at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, and Nathaniel Grossman, an editorial and program associate at Fordham, written expressly for reimgainED, explores the myths and misperceptions about charter schools.

More than two years ago, a Florida newspaper editorial board made two incriminatory claims: “Charter school companies feast at the public trough,” and “There’s no consensus on whether charters are doing as well, better, or worse than the traditional model in educating children.”

That would be a big deal, if true. Florida has over 600 publicly-funded charter schools, so it’s imperative that parents, students, educators, and the larger public know whether these claims have merit. However, research conducted in the last several years says otherwise—and it’s a problem that these misconceptions continue to fester.

Let’s first clarify the term “charter school companies.” Like those nationwide, public charter schools in Florida are governed and regulated by public agencies and must operate as non-profit organizations run by their own boards. Those boards may—and many do—opt to enter into contracts with for-profit or non-profit management organizations that provide specific services for one or more schools.

This is done in the interests of quality and efficiency, just as traditional public schools obtain various administrative and academic supports—payroll, accounting, hiring, and so on—from their central offices, and everything from cafeteria food to teacher professional development from outside vendors. Charter schools that enter into contracts with for-profit organizations are often wrongly referred to as “for-profit charters,” despite the fact that they are non-profit schools.

Let’s now turn to the claim that these organizations are “feasting at the public trough.” Make no mistake, fiscal impropriety exists in every school sector—both traditional and charter—and it’s obviously unacceptable. But no one has access to the internal budgets or earnings reports of the for-profit organizations contracted to help schools in the Sunshine State. Moreover, we’re not opposed to reasonable levels of transparency (versus trying to overregulate the sector out of existence), including public reporting of data pertaining to expenditures and profits. But until we have that—in the traditional school sector, too, we might add—accusations of profiteering in Florida’s charter schools are simply unfounded.

What we do know, however, is that public charter schools typically educate students for less money than traditional district schools. For example, in Florida, charter schools received an average of $6,500–$7,400 per student in the 2019–2020 school year, below the average of $7,672 for traditional schools. We also know that so-called “for-profit charter schools” in Florida that belong to a network spend 11 percent less than schools with non-profit management organizations, and do so without cutting expenses on instruction.

A recent study published by our organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, likewise found that charter schools in Ohio that outsource work to for-profit entities tend to spend more money on classroom instruction than traditional public schools. In other words, they receive less public funding but keep dollars where they belong: in the classroom.

This leads to the second dubious claim that there’s “no consensus” on the effectiveness of charter schools. The Fordham study mentioned above also found that both non-profit and for-profit charter schools tend to outperform traditional public schools, even with less funding per student. Furthermore, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that attending a school operated by the National Heritage Academy, the fourth-largest for-profit charter network in the nation, is associated with higher student achievement in math.

As for Florida, a 2017 Stanford University study praised its hybrid schools—in which a charter management organization chooses the school operator—for their “exceptional success” in driving student achievement in math and reading. Across the 26 jurisdictions in the study, Hispanic students who attended hybrid charter schools gained what amounted to 74 additional days of math growth and 63 additional days of reading growth per year over similar peers who attended traditional public schools. As explained in the study, these large effects were driven “primarily by the exceptional success of the Hybrid schools in Florida and Michigan.”

What’s more, the benefits of charters aren’t limited to the students that they enroll. At least a dozen rigorous academic studies have now shown that competition from charters has positive effects on the academic achievement of students who remain in traditional schools. In fact, another recent Fordham study found that these effects are so profound and broadly shared that they benefit entire metropolitan areas, especially those students who are low-income, Black, and Hispanic. Still another study we recently released showed that teachers in charter schools tend to have higher expectations for students than do their counterparts in traditional public schools, which research shows can lead to a host of improved outcomes for students, including greater high school graduation and college completion rates.

Every school has room to improve, and that certainly includes the charters that partner with for-profit companies for services. But on average, the evidence leads us to believe that public charter schools—in all their forms—can be beneficial to students. So try to keep an open mind when you hear about that popular misnomer otherwise known as for-profit charter schools.

Students at Wimauma Community Academy work with a drone provided by a donor.

The students at Wimauma Community Academy were so determined to win an online math competition that they came to school over the weekend to stay at the top of the leaderboard. At a school where about 95% of the students live below the federal poverty level and don’t have Wi-Fi at home, that was the only way they could compete for the $15,000 prize

Despite their challenges, the students are excelling thanks to Redlands Christian Migrant Association, which established two Florida charter schools in 2000 for children of migrant farmworkers.

“We’re proud that we’re a public charter school and that we are nonprofit,” said Juana Brown, the organization’s director of charter schools. “Some of these babies who started out in our migrant Head Start programs are actually teaching in our schools. It’s a beautiful thing to come full circle.”

The students won the math competition and took home the prize, which school leaders used to build a pavilion on their campus in a rural area southeast of Tampa, Florida. The victory earned them local media attention.

This year, Redlands, which operates the Wimauma school and another charter school in the rural southwest Florida community of Immokalee, has attracted national attention as one of 32 semifinalists for the Yass Prize. Philanthropist Janine Yass founded the awards program in 2021 to reward the innovation in education that resulted from the pandemic with a focus in underserved populations.

Since last year, the awards program, formerly known as the STOP Awards, has broadened its scope to innovation beyond the pandemic. It also included more grants as well as an accelerator to help the entrepreneurs learn from experts and each other.

(John F. Kirtley, founder and chairman of Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, is part of a blue-ribbon panel of Yass Prize winners from last year and supporters of education choice who are evaluating this year’s entries.)

The 64 quarterfinalists, announced in October, each received a $100,000 award. Those who went on to be named semifinalists received $200,000. The finalists will be announced Dec. 14 and receive $250,000. The overall winner will receive the $1 million Yass Prize. (You can read about last year’s top winner here.)

Wimauma Community Academy serves students in kindergarten through eighth grade whose parents are migrant farmworkers. A sister charter school, Immokalee Community School, serves students in kindergarten through seventh grade.

RCMA Immokalee Academy is one of two charter schools founded by Redlands Christian Migrant Association in 2000. RCMA is one of 32 semifinalists for the $1 million Yass Prize and has received $200,000, which leaders plans to put toward expansion.

RCMA’s mission focuses on improving the quality of life for Florida migrant families through education from “the crib to high school and beyond” and wraparound care that includes training and social services.

The organization operates childcare centers in 21 of Florida’s 67 counties. In addition to providing a safe place for children to learn while their parents are working, the centers also serve as community hubs, linking families to social services such as health care and providing training in such subjects as GED classes, nutrition, parenting, language, and household management.

A group of Mennonites founded the organization in 1965 after seeing young children having to spend all day in unsafe conditions while their parents picked produce in the fields. Kids were being exposed to pesticides and the pests they were targeting. One child died after falling into a drainage ditch.

“Children were sleeping in trucks,” Brown said. “There was no accessible and affordable child care.”

After opening a childcare center to serve the families and seeing few takers, the Mennonites decided to train migrant mothers and employ them to staff the center. After that, the families poured in.

As more families requested expanded education opportunities for their school-aged children, RCMA opened the two elementary schools in 2000.

Ten years later, RCMA added a middle school, RCMA Leadership Academy, to its Wimauma campus. Both Wimauma schools serve a total of 300 students.

Wimauma Academy third graders scored in the top 20 in the state in math. At RCMA Leadership Academy, 29 of the seventh- and eighth-grade scholars entered high school this year with Algebra I credits and nine with Algebra I and geometry. In civics, the seventh graders’ proficiency scores beat the state and county, and eighth graders topped the state and county in science.

Like the school in Wimauma, the Immokalee School received a “B” grade from the state. In May, the Florida Board of Education designated RCMA as an operator in its Schools of Hope program. The designation allows RCMA to open schools in neighborhoods where a traditional public school has been persistently low-performing and/or is within a Florida Opportunity Zone.

The designation makes RCMA eligible for state funds and low-interest loans as the 57-year-old nonprofit organization expands its charter school operations.

“This is the first year our sixth-graders are taking algebra,” Brown said. “We believe our students are extraordinarily talented and gifted and with the right support can be successful.”

In addition to core academic subjects, the schools offer families fresh produce, which ironically is not accessible or affordable to them even though they harvest it.

“Most of them live in food deserts,” Brown said.

So, the students planted their own vegetable gardens to help families with nutritional needs. In Wimauma, the school brought in chickens to help with pest control. Students who cared for the fowl called their group “The Chicken Tenders.”

The organization features alumni success stories on its website. One of its former students, Zulaika Quintero, attended the University of Florida on a full academic scholarship and now is principal at the Immokalee Community Academy.

The Charter School Growth Fund, the largest funder of high performing charter schools in the country, pledges a $1.275 million investment over four years to help RCMA expand its schools.

RCMA plans to open the K-8 Mulberry Community Academy for the 2023-2024 school year, followed by another K-8 school in Immokalee and a K-8 school in Miami-Dade County. But RCMA doesn’t plan to limit its growth to the Sunshine State, Brown said. The nonprofit’s goal is to provide support for those seeking to establish programs in other states to help immigrants.

“I believe our model is one that serves families that are making that transition, and I think we have an educational model that supports the children and the families,” said Brown, who came to the United States from Cuba when she was 7 and knew no English. “We can give you some things we believe can make a big difference.”

Ninety-eight percent of the 361 students at AcadeMir Charter School Middle in Miami, designated a National Blue Ribbon School, are Hispanic. The school promotes self-motivation in all subject areas, especially mathematics, science, reading and technology.

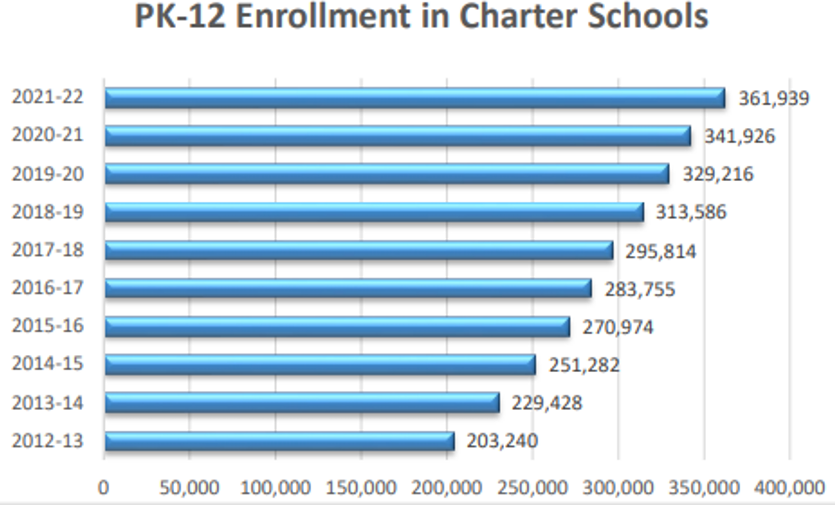

Charter school enrollment in the Sunshine State increased by 20,013 students in the 2021-22 school year according to data released by the Florida Department of Education.

More than 360,000 students enrolled in one of 703 charter schools, a growth of 5.8% over the prior year.

Unlike private schools, which suffered the first enrollment declines in a decade during the COVID-19 pandemic, charter schools, which are privately run tuition-free public schools, never saw a dip during that time, growing by 3.8% in the first year of the pandemic while home education grew by 35.2%.

The Department reports that of the 51% of charter school students who qualify for free or reduced-price meals, 45.1% are Hispanic, 29.6% are white, and 18.8% are Black.

The Department reports that of the 51% of charter school students who qualify for free or reduced-price meals, 45.1% are Hispanic, 29.6% are white, and 18.8% are Black.

Like district-run public schools, charters are subject to state A-F grades. Forty-five percent of charter schools earned an “A” grade, 32% earned a “B,” and 26% earned a “C”. Only eight schools earned an “F” grade.

Unlike district-run public schools, charters can be shut down for consecutive “F” grades.

In 2021, 80 organizations applied to start a new charter school. Only 51.3% of those applications were approved according to Department. Charter schools are approved by their competing school districts but may appeal to the State Board of Education.

Karen McCabe, a former director of the South Santa Rosa Center at Pensacola State College, has been selected as principal of Pensacola State College Charter Academy. In its inaugural year, the academy is serving 150 students from military families and students deemed at risk of dropping out.

As the rising cost of college continues to push higher education out of reach, programs that allow high schoolers to earn college credits are soaring in popularity. Many dual enrollment programs traditionally have been offered within public and private high schools, while others have allowed students to attend classes on the campus of the participating college.

Now, colleges such as Pensacola State College in Florida’s Panhandle are bringing entire high schools to their campuses for dual enrollment, offering students the chance to earn an associate degree alongside a high school diploma.

Pensacola State College Charter Academy opened Aug. 8 on the college’s Warrington campus to about 150 students from military families and students deemed at risk of dropping out.

"(Military) children may be in one school for two years, another one for two years, another one for two years. Their parents are always looking for quality opportunities for their children, so this gives them another choice," Capt. Tim Kinsella, base commander of Naval Air Station Pensacola, told the Pensacola News Journal.

"It gives them an opportunity that is something more than just a high school because of the opportunities that this presents. It's almost an attraction for military families to come here."

Pensacola State College Charter Academy’s inaugural class is comprised of high school juniors and seniors; sophomores will be accepted in the fall of 2024. About 80% of students were required to meet charter school entry requirements, while 20% of the space was reserved for students specifically at risk of dropping out. Military families are exempt from meeting the entry requirements.

Authorized by the Escambia County School District, the academy got a funding boost with a $100,000 donation from the Gulf Power Foundation toward a technology innovations center, housed within the school, which will offer students access to virtual simulations of various types of careers.

"It'll be more than just access to the internet,” academy president Ed Meadows said.

Karen McCabe, a former school principal in New York and director of the South Santa Rosa Center at Pensacola State, was tapped to be principal at the new charter academy. During her tenure at the Santa Rosa Center, she worked with two of the largest local high schools to offer dual enrollment with the college and helped to increase participation.

The academy will focus heavily on careers, particularly those grounded in science, technology, engineering and math. Students will be required to complete a capstone project related to their desired career path prior to graduation.

“They will do some heavy research with an individual in that field and possibly shadow them,” McCabe told Pensacola’s WEAR-TV.

Pensacola State College Charter Academy is part of the dual enrollment boom that has taken the nation by storm in recent years. Between the 2002-03 and 2010-11 academic years, the number of high school students taking college courses for credit increased by 68% to nearly 1.4 million according to federal data. By 2015, nearly 70% of high schools offered dual enrollment, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Hailed as game-changers for lower-income students, the programs have allowed many to get a free head start on a college degree they otherwise might not be able to afford. The programs also help local colleges, which have seen enrollments plummet since the end of the Great Recession in 2010.

In Florida, an 8-year-old legal glitch that left no funding for nonpublic schools to provide dual enrollment resulted in a 60% drop in enrollment among independent and faith-based schools. The Florida Legislature in 2021 corrected the problem by passing SB 52, which set aside $15.5 million in state money to cover the costs for homeschooled and private school students who participate in dual enrollment programs by taking courses from a partnering college or university.

The legislation was a top priority of private school leaders, who had been forced to stop offering dual enrollment at their high schools because of the costs. Many, including Steve Hicks, vice president of operations for Center Academy, which operates 10 campuses in Florida for students with learning disabilities, praised lawmakers for passing the legislation.

“Studies clearly show that students who have an opportunity to take dual enrollment courses are more likely to attend a college after high school,” Hicks said. “The fact that so many families, like the ones we serve, were not able to take advantage of this opportunity due to financial or other reasons was extremely frustrating.”