Two states, Maine and Vermont, have devised ways to circumvent the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Espinoza vs. Montana.

States can’t discriminate against religious schools because of their religious identity. But can states discriminate if the school teaches religious things?

If you thought this debate was settled by the U.S. Supreme Court last summer, think again.

Two recent circuit court rulings say yes, states can discriminate against religious instruction. Lawyers for the Institute for Justice briefed the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this month and are waiting to hear if the nation’s highest court will resolve this issue once and for all.

The 2020 landmark Supreme Court case Espinoza v. Montana was supposed to settle the debate over “separation of church and state” in publicly funded education programs. That ruling determined that, “A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.”

Despite this proclamation, Maine and Vermont have found clever ways to ignore the court ruling.

Maine has been offering publicly funded private education through a town tuition assistance program since 1873. The program is available to students living in towns without an available public school. Students may choose to attend a public school in another town or attend a private school. That private school, however, cannot be religious in nature.

But just a few months after the Espinoza ruling, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the religious exclusion in Maine’s program.

The court got clever with the wording. The judges argued that the Espinoza case prohibited states from discriminating against the schools’ religious status, whereas Maine was not discriminating against religious status but prohibiting religious use.

In other words, Maine’s ban on selecting private religious schools was not over the school’s religious identity, but because the religious school taught religious things.

It may be a distinction without meaning.

Could religious schools in Maine receive publicly funded tuition if they did not provide the publicly funded student religious instruction? That is unclear, as Maine’s prohibition appears to be a blanket ban.

The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a similar argument in a case over Vermont’s tuition program earlier this month.

The Institute for Justice, which represented parents, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court to take up the Maine case.

“Maine is discriminating against students that pick religious schools and the High Court should grant review and put an end to such exclusions nationwide,” Institute for Justice managing attorney Arif Panju said in a press release. “By singling out religion—and only religion—for exclusion from its tuition assistance program, Maine violates the U.S. Constitution.”

The U.S. Supreme Court justices will consider on June 24 whether to grant review.

You can read the Institute’s Supreme Court brief here and supplemental brief here.

*Updated to clarify the results of the Vermont case decided on June 2nd.

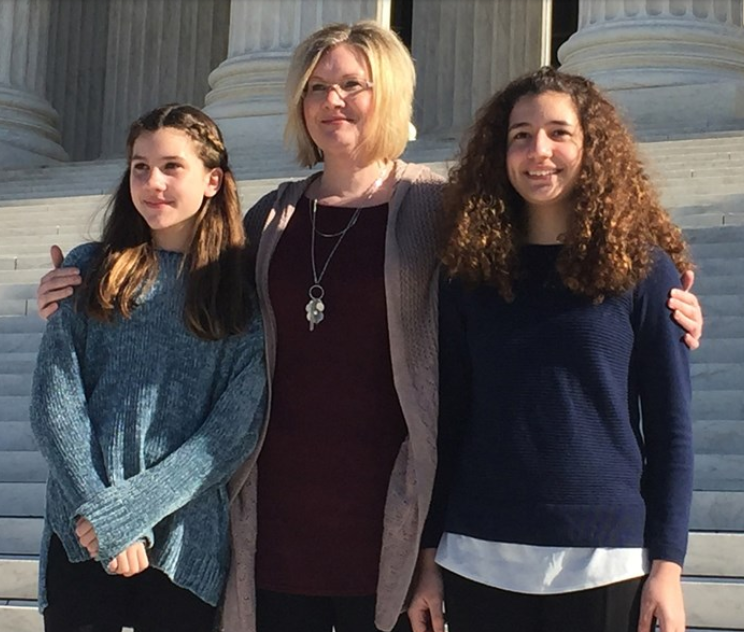

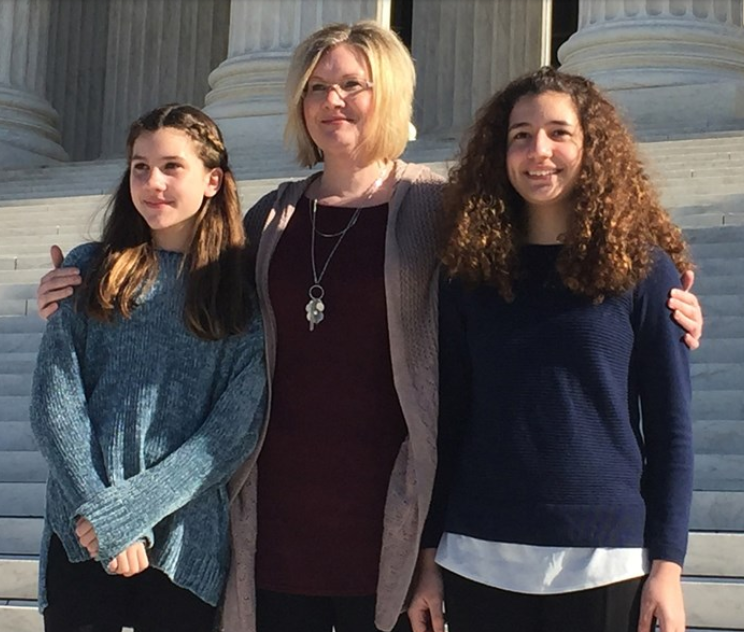

Kendra Espinoza of Kalispell, Montana, lead plaintiff in the case, with her daughters Naomi and Sarah outside the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., in January.

Editor’s note: During the holiday season, redefinED is reprising the "best of the best" from our 2020 archives. This post originally published June 30.

![]() In a landmark decision today on school choice, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Montana Department of Revenue’s shutdown of a tax-credit scholarship program for low-income students is unconstitutional, potentially opening the door for states to enact such programs for students to attend private faith-based schools.

In a landmark decision today on school choice, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Montana Department of Revenue’s shutdown of a tax-credit scholarship program for low-income students is unconstitutional, potentially opening the door for states to enact such programs for students to attend private faith-based schools.

The court said in its 5-4 decision on Espinoza vs. the Montana Department of Revenue, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, that the Montana Department of Revenue cannot disqualify religious schools simply because of what they are.

“A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious,” the opinion said.

The ruling also stated:

“Drawing on ‘enduring American tradition,’ we have long recognized the rights of parents to direct ‘the religious upbringing’ of their children … Many parents exercise that right by sending their children to religious schools, a choice protected by the Constitution.”

Roberts was joined by Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch. Dissenting were Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer.

“The Supreme Court delivered a major victory to parents who want to choose the best school for their children, including religious schools,” said Institute for Justice senior attorney Erica Smith, who was co-counsel on the case. “This is a landmark case in education that will allow states across the country to enact educational choice programs that give parents maximum educational options.”

Organizations that support education choice praised the decision.

“It’s a good news day for those who love the freedoms we enjoy in this country and seek to advance and preserve those freedoms,” said Leslie Hiner, leader of the Legal Defense & Education Center for the nonprofit advocacy group EdChoice. “Today the Supreme Court has re-affirmed its role as the guardians of our Constitution. The Montana Supreme Court has disregarded the U.S. Constitution, and in particular the First Amendment’s clause protecting our right to the Free Exercise of whatever faith we choose as individuals, when it struck down a modest school choice program that allowed parents to choose any school, religiously-affiliated or not, for their children’s education.”

The case started in 2015, when the Montana Legislature enacted a program that provided a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for taxpayers who donated to a Student Scholarship Organization. That meant a Montana resident could donate to a scholar organization, and in turn, would receive a tax credit for the donation.

The Student Scholarship Organization used the donated money to provide scholarships to students to attend private schools, including private schools affiliated with a religion.

Shortly after the program was enacted, the Montana Department of Revenue promulgated an administrative rule (“Rule 1”) prohibiting scholarship recipients from using their scholarships at religious schools, citing a provision of the state constitution that prohibits “direct or indirect” public funding of religiously affiliated educational programs.

Kendra Espinoza and the two other mothers filed a lawsuit in state court challenging the rule. The trial court determined that the scholarship program was constitutional without the rule and granted the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment. On appeal, the Department of Revenue argued that the program is unconstitutional without Rule 1. The Montana Supreme Court agreed with the Department and reversed the lower court.

At issue in the case are Blaine Amendments, also called “No Aid” clauses, which are provisions in 38 state constitutions, including Florida’s, that bar public aid to religious organizations. They get their name from James G. Blaine, a congressional representative and later senator and presidential nominee from Maine who unsuccessfully attempted to amend the U.S. constitution in 1875 to include “anti-aid” language onto the end of the first amendment. Where he failed at the federal level, many states inserted Blaine Amendments into their constitutions. As a result, Blaine Amendments frequently act as state-level barriers against school choice.

“I am thrilled that the courts ruled in favor of the Constitution and maintained a parent’s right to choose where their children go to school,” Espinoza said in a news release issued by the Institute for Justice. “For our family, this means we can continue to receive assistance that is a lifeline to our ability to stay at Stillwater. For so many other families across America, this will potentially mean changing lives and positively altering the future of thousands of children nationwide. What a wonderful victory.”

The win and the promise of continued scholarships is a significant boost to Espinoza, who has had to work multiple jobs, including cleaning houses and doing janitorial work, to afford her daughters’ tuition payments at a private Christian school in Kalispell. Kendra transferred her two daughters to Stillwater Christian School after they struggled in their public school. Montana’s scholarship program has helped Kendra and families across the state keep their children in the school that works best for them.

“It’s been a century-and-a-half since the bigoted Blaine movement took root in state constitutions throughout the country,” IJ Senior Attorney Richard Komer, who argued the case before the Court said in the news release. “Today’s decision shows that it is never too late to correct an injustice, even one with as long and ignoble a pedigree as this one.”

Today’s decision will affect most of the 14 states that have strictly interpreted their state constitution Blaine Amendments to bar scholarships to children at religious schools. For decades, the creation and expansion of school choice programs have been inhibited by legislative concerns that they might conflict with state constitutions. Those concerns are now removed with today’s decision in Espinoza.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Ben DeGrow, director of education policy for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Midland, Mich., published Monday on The Hill.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Ben DeGrow, director of education policy for the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Midland, Mich., published Monday on The Hill.

The once-forecasted political “blue wave” offered labor leaders and their partisan allies the hope of rolling back educational choice, but that wave never arrived. With Democrats unable to take over new state levers of power, they and union officials instead may be facing a torrent of new initiatives to give students and families more opportunities.

In this most unusual year, the coronavirus pandemic has opened many parents’ eyes to the brutal shortcomings that pervade K-12 education, and voters returned to office more policymakers who are willing and able to take a stand on parents’ behalf. Labor leaders and bureaucrats accustomed to running the school system should brace themselves for a jolt of parent power.

Using emergency CARES Act funds, some states already have revealed new strategies to fund students directly during the pandemic. For example, Texas and Ohio authorized $1,500 microgrants to families to help them supplement the special education services their disabled children receive while in-person instruction is unavailable.

Friendly leaders in the nation’s capital have demonstrated an unprecedented level of backing for choice over the past four years. It’s one issue that increasingly resonates with voters across the political spectrum — almost 70 percent favor expanding choice.

Ten years ago, a “red wave” handed over the keys to many state legislatures and governors’ mansions to a political party not beholden to teachers unions. That fresh burst of lawmaking energy turned 2011 into the Year of School Choice, as state leaders across the country adopted 18 new voucher, tax-credit scholarship and education savings account programs. Many thousands of students experienced new opportunities as a result.

This month, dozens of pro-school choice officials won election in a number of key states, according to the American Federation for Children. A growing and diverse coalition of frustrated parents may prompt these lawmakers to open new approaches to help children succeed. They could expand private school choice programs like the ones formed a decade ago, and add fresh kinds of aid that enable families with lesser means to work directly with teachers in setting up learning pods.

Parents’ hopes are also backed by a powerful legal precedent. Last June’s groundbreaking Espinoza ruling at the U.S. Supreme Court bars state courts from using archaic constitutional provisions to block parents from choosing private, religious schools when they use publicly funded scholarships. In fact, the state where the Espinoza case originated soon may be part of the vanguard. The election of a new Montana governor places state control entirely in Republican hands, opening up possibilities for more robust programs than the small 2015 scholarship initiative that triggered the case.

As states take up the cause, choice supporters should look to Florida to see where legislative work could lead. A statewide nonprofit there recently handed out the millionth scholarship to a low-income K-12 student, in a story that stretches back nearly 20 years. Those scholarships are funded by corporate donations that receive tax write-offs, the result of a 2001 law adopted under then-Gov. Jeb Bush. The scholarships help many academically struggling students rise to the educational level of their more advantaged peers.

The votes of Black mothers whose children benefit from Florida’s K-12 scholarships put Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis over the finish line during the 2018 election. With lawmakers from both parties, he has worked to deliver more choice to families in a state where accessible education options already are common.

While a few states may be ready to follow in Florida’s steps, school choice survived an onslaught in a different state. The union-supported “Red for Ed” movement aimed to scale back one of the nation’s most robust array of educational choices in Arizona. Yet voters, who appear to have narrowly rejected both the president and the incumbent Republican U.S. senator, also dashed Democratic hopes of taking over either chamber of the legislature.

Across the continent, in a state President-elect Joe Biden won easily, New Hampshire completely reversed a 2018 Democratic takeover that, last year, prompted efforts to squash a smaller version of a Florida-style scholarship tax-credit program. With the proposed repeal now on ice, a fresh batch of legislators soon will have the chance to expand educational opportunity in the Granite State.

Newly energized by students and parents in need, reform-minded policymakers across the nation are poised to expand the bounds of learning opportunities. If their actions make possible a new wave of successful students and satisfied parents, they could transform education in the U.S. for decades to come.

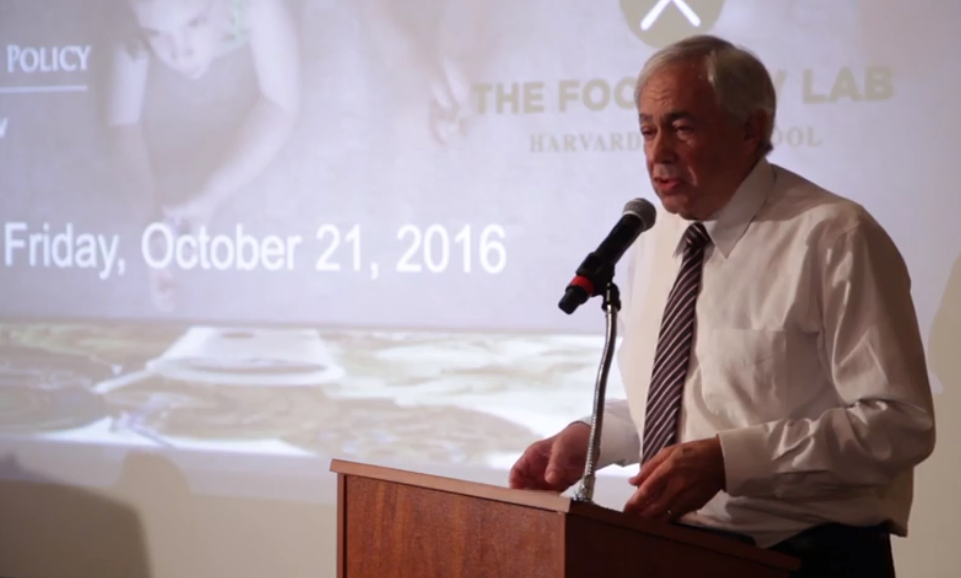

Berkeley Law giant Stephen Sugarman, an icon of the education choice movement, speaks about constitutional and regulatory frameworks at a Resnick Program and Harvard Law Lab’s conference in October 2016.

In the last of a three-part podcast series, Tuthill and Berkeley law professor Sugarman discuss the landmark Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue Supreme Court decision.

The June 2020 decision made it clear that a state cannot exclude religious schools from receiving funding from a program created by the state to fund private education. Chief Justice John Roberts clearly echoed Sugarman’s writing in the 5-4 decision.

In Sugarman’s analysis, there is a fundamental disagreement between the judges as to how the Court will continue to resolve the tension between the Free Exercise and Establishment clauses of the Constitution.

“Montana lawyers relied on (their interpretation of) the Blaine Amendment. They said, “not only do we not want to help these Catholic schools, we cannot. … and the Supreme Court said no; the Free Exercise Clause trumps ... the Blaine Amendment.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

· The history behind anti-Catholic sentiment after the Civil War that fueled the adoption of “Blaine Amendments” all over the country

· How Chief Justice Roberts’ decision in Espinoza echoed Sugarman’s argument for allowing faith-based organizations to operate charter schools

· Justices Breyer, Thomas and Alito’s writings in the Espinoza decision and the tension among different opinions

· How America differs from other modern countries that fund K-12-aged religious schools if they meet regulations

· Charles Glenn’s research suggesting that allowing families to educate their children in schools that reflect their religious faith strengthens the cohesion of democracy

LINKS MENTIONED:

Sugarman – Is it Unconstitutional to Prohibit Faith-Based Schools from Becoming Charter Schools?

Notable SCOTUS education choice decisions - Locke v. Davey

Notable SCOTUS education choice decisions -Trinity Lutheran v. Comer

Listen to Part 1 of Tuthill’s conversation with Sugarman here.

Listen to Part 2 of Tuthill’s conversation with Sugarman here.

Berkeley Law professors John C. Coons, left, and Stephen Sugarman, circa 1978.

On this episode, Tuthill continues his conversation with education choice pioneer Stephen Sugarman of Berkeley Law School. The two discuss Sugarman’s 2017 article in the Journal of Law and Religion in which Sugarman argues that prohibiting faith-based schools from becoming charter schools is unconstitutional under the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.

Sugarman’s argument that it’s unconstitutional to exclude faith-based organizations from participating once a state has chosen to fund alternative education options was echoed earlier this year in the landmark Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue. On the podcast, he reviews the history of two notable U.S. Supreme Court cases, Locke v. Davey and Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, and how their precedents laid the groundwork for the Espinoza decision.

"There should be some room (for education choice funding) between what is forbidden by the Establishment Clause and what is required by the Free Exercise Clause. Funding choice (does) not violate the Establishment Clause.

EPISODE DETAILS:

· Sugarman’s 2017 article on the constitutionality of faith-based charter schools

· Locke v. Davey and Chief Justice Rehnquist’s explanation of the “play-of-the-joints” between the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses of the Constitution

· How teacher union hostility toward charter schools has caused the public to mistakenly think they’re private rather than public schools

· How a faith-based organization can operate a charter school by state policy while continuing to practice religious observances outside of classroom time

LINKS MENTIONED:

Sugarman: Is it unconstitutional to prohibit faith-based schools from becoming charter schools?

podcastED: SUFS President Doug Tuthill interviews education choice icon Stephen Sugarman – Part 1

You can watch Part 1 of Tuthill’s interview with Sugarman here.

If all want sense, God takes a text

And preaches patience.

The Church Porch, Geo. Spencer

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has given us a decision in Espinoza v. Montana, suppose that one day the state of Montucky were to adopt a broad and inviting program of subsidies for lower-income parents to choose among private schools that are free to teach religion. One systemic effect of such an act would be new pressure on the public school to begin behaving in ways that attract parents who would no longer be conscripts, but rather, free customers.

In a word, there would be competition.

Experience already tells us that one substantial effect of choice is to lure to the private sector parents who have religious beliefs that could at last be served and celebrated in private school. Plainly put, the governmental sector of schooling would be at some disadvantage in a market where, by law, it could not serve such families’ preferences by teaching about God as the parent would have it.

There seems little prospect of the Court in any future decision allowing public schools to compete simply by adding religion to its ordinary curriculum. Which religion(s) would they teach, and what of the rights of dissenting and atheist parents? Are there options for P.S. 42 – that is, could public schools at least do something that would recognize the importance of the intellectual, spiritual and moral issues involved without favoring any particular belief over others?

Could they do something more than offering an hour’s “release time” once a week with some unpaid priest, pastor or rabbi who sets aside all other distracting duties for this one, for which he or she may be poorly prepared?

The alternative available to the public school may be awkward, but I should not give up on making religion, agnosticism and atheism all teachable with enthusiasm in the basic curriculum – and without violating the establishment clause of the First Amendment. There is, I think a way for the classroom teacher (or better, a certified and scheduled specialist), in the regular curriculum to do justice to contrary ideas without betraying his or her own convictions; it would have its occasional moments of disaster, but no more frequently or damaging than the available alternatives.

Moreover, it could open young minds to ways of thinking and of respectful disagreement on this world’s most fundamental issue.

This method that I have I mind is very old and always imperfect, but I think it a plausible exit from the public school’s looming problem of keeping those families who would now have become its free customers. The effective teaching of religion in public elementary and high school should be taken seriously as part of the teacher training for the Master of Arts, and at least some graduates should finish sufficiently adept that their handling of the transcendental could claim neutrality.

Without settling upon a “correct” answer for the pupil to memorize, the child would at very least be helped to understand that there is a crucial question all humans have faced since the beginning – from Eve in the Garden of Eden to politicians in the Rose Garden.

This method that is plausibly lawful is generally labeled “Socratic,” thus paying tribute to that old Greek who left us nothing written but who gave philosophy and law a way of separating ideas that are either mutually opposed or simply different, and to do so without taking a side.

And here is a confession: I draw upon forty-plus years of experience teaching law to (mostly) young adults and not to children (except our own five) and that experience may be too remote from childhood and adolescence to justify my pontificating about the ideal pedagogy for elementary or high school pupils.

Whether Socrates ever visited his style upon children, we don’t know. But were I teaching in the public schools of 2040, I would at least give the old Greek – and myself – a serious try.

“Like to one more rich in hope.”

“Like to one more rich in hope.”

Twelfth Night, Shakespeare

The media are calling the long-awaited U.S. Supreme Court decision in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue a victory for “conservatives.” The Court has liberated a few low-income Montana families from conscription by the state and the teachers union, and yet we hear this rescue is “conservative.”

It is, I concede, an act of conservation, preserving the basic legal authority of the poor over their own children. These parents are, to a limited degree, made free to participate in the great school market. It is a victory for the lower-income family – but conservative?

Could it be that our English language is, for this scenario, simply lacking in resource to describe the reality? If you don’t like the judicial outcome of some dispute, you are free to call it whatever you think will give it a black eye in your own intellectual neighborhood. Hence, “conservative” we shall hear.

Last week’s decision is a powerful, if very limited, reaffirmation of the basic constitutional right, authority, and power, even of low-income parents, to decide just what style and content of formal schooling their child will experience – what teacher we shall allow to instruct their child in the skills she or he may need and what version of human origin and personal perfection will be delivered to these young minds for whom we are so full of hope.

The decision reminds us that 95 years ago, a case titled Pierce v. Society of Sisters et al. gave America the basic precept that parents – not the State – have the authority to decide where Susie goes to school. But a fundamental problem has remained: If you are not well-off, how can you exercise that authority by paying tuition? And, if you can’t do so, will the government that makes school compulsory leave you helpless with no option but P.S. 42? Must Susie go where strangers – i.e., “the State” – decide to send her?

So far in history, government has shown little interest in assisting the exercise of your parental authority. The primary concern of its legislatures and its governors has been to keep the teachers union electing them.

The Montana decision will not by itself end this great shadow on human liberty and authority. But the majority opinion justifies hope for development of ever more radical motions (“conservative,” if you prefer). The majority opinion by the chief justice relies exclusively upon the First Amendment’s guarantee that “Congress shall make no law … prohibiting the free exercise” of religion, extended by the 14th Amendment to limit the states.

One can wonder (“conservatively”?) about the regimes of public schooling born of 19th century anti-Romanism by which schools became mandatory, but those elite who could afford it could, and still do, go private or religious at their choice.

Is it still constitutionally sound for a state to make schooling a parental duty, but then to protect choice only for the well-off? Will the Court let the inner-city “public” school last forever it its captive mission, thus saving the bacon for officers of the teachers union?

Talk to your state legislator – and stay tuned to the conservative Court.

Dick Komer retired in May after a quarter-century at the Institute for Justice, helping countless families obtain greater choice to meet their educational needs. He is known throughout the educational choice movement as the consummate expert on crafting choice programs that can withstand lawsuits from choice opponents.

Bigots spent an enormous amount of effort in the late 19th century enshrining their hostility to Catholics and Jews into dozens of state constitutions in the form of Blaine Amendments. They quite nearly amended the federal Constitution as well.

It was never going to be easy to undo, but it has been done.

This Blaine Amendment movement supported by the likes of the Know-Nothing Party and the Ku Klux Klan reeked of illiberal intent. In the 1920s, the Know-Nothings and the Klan managed to make it illegal to send a child to a private school at all, making attendance at a public school with a Klan-approved curriculum mandatory so as to meld people into what the Klan considered “real Americans.”

While the U.S. Supreme Court struck this law down, Blaine Amendments remained in effect. It took multiple careers-worth of sustained effort to chip away at these relics, including that of the great Dick Komer, pictured above, who came out of retirement to argue the Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue case.

Komer has long been one of the treasurers of the education choice movement. To meet him is to love him. Not even his consistent and hilariously expressive swearing can distract you from his warm heart and keen intellect.

Blaine, the Know-Nothings and the Klan met their match once Komer and the many other dedicated attorneys at the Institute for Justice put their mind to it across a string of cases stretching over decades. Komer not only won the big case; he served as an inspiration and example to the choice movement for how to be a happy warrior.

Enjoy your retirement Dick, and thank you for your service.

After more than a century, the U.S. Supreme Court finally has determined that Blaine amendments, which were created in the late 19th century under a wave of anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic bias, violate the U.S. Constitution’s Free Exercise clause.

After more than a century, the U.S. Supreme Court finally has determined that Blaine amendments, which were created in the late 19th century under a wave of anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic bias, violate the U.S. Constitution’s Free Exercise clause.

"A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious,” ruled the U.S. Supreme Court in a 5-4 decision this week.

Montana’s school choice program became the first tax credit scholarship to be struck down by a state supreme court, but not the first private school choice program to be struck down because of a “Blaine Amendment.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling reverses the Montana Supreme Court, arguing the state’s “No Aid” provision violates the rights of parents, students and religious schools under the Free Exercise Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

The ruling is in step with the Trinity Lutheran (2017) decision which argued denying grants for playground resurfacing simply because the institution was religious was unconstitutional.

Though the Court ruled that the Blaine Amendment violates the Free Exercise clause, it declined to rule whether it also violated the Establishment Clause or Equal Protections Clause.

Not surprisingly, school choice opponents are up in arms about the decision.

“… the court has made things even worse opening the door for further attacks on state decisions not to fund religious schools,” said National Education Association president Lily Eskelsen García in an NEA blog post.

But the court’s decision does nothing of the sort. The decision to create and fund education scholarships still falls to the people.

Other school choice opponents are arguing the decision erodes separation of church and state.

Ron Meyer, lawyer for the Florida Education Association, went so far as to state in an interview with the Miami Herald, “It’s another chipping away of the free exercise of religion.”

But the decision falls in line with a long-standing recognition of religious neutrality required of governments. Though many of these cases deal with the Establishment Clause rather than the Free Exercise Clause, they demonstrate this long-standing precedent on religious neutrality.

The first case to apply the Free Exercise clause to a state matter was Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), which reversed a criminal conviction of three Jehovah’s Witnesses for proselytizing door-to-door without a state license. In a unanimous decision the court ruled:

“Freedom of conscience and freedom to adhere to such religious organization or form of worship as the individual may choose cannot be restricted by law. On the other hand, it safeguards the free exercise of the chosen form of religion. Thus, the Amendment embraces two concepts, freedom to believe and freedom to act.”

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the court defined the Establishment Clause beyond simply establishing a national church by declaring the clause prohibited the aid of one religion or even all religions. However, the court still upheld public bus fare reimbursements to parents sending their children to Catholic schools because the reimbursement was available to all. Regarding New Jersey’s publicly funded programs, the court ruled:

“Consequently, it cannot exclude individual Catholics, Lutherans, Mohammedans, Baptists, Jews, Methodists, Non-believers, Presbyterians, or the members of any other faith, because of their faith, or lack of it, from receiving the benefits of public welfare legislation.”

In Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the U.S. Supreme Court held Ohio's voucher program “does not offend the Establishment Clause” because the program was neutral with respect to religion.

As with Zelman, several other national cases support tax exemptions and other public benefits for seemingly religious activities, but only so long as the programs pass the “Lemon Test.”

Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) established the “Lemon Test,” a three-part test to determine if a program violates the Establishment Clause. The test requires the program to have a secular purpose, to not advance or inhibit any particular religion, and to not excessively tangle government with religion. In Lemon, the court allowed state subsidies of textbooks, educational materials and even teacher salaries at private schools in Pennsylvania.

Mueller v. Allen (1983) upheld a Minnesota tax law that allowed individuals to deduct parochial school expenses. The Supreme Court ruled the program was neutral with respect to religion since the tax deduction was available to all, and that helping to fund education (even through tax deductions) was a secular purpose.

Agostini v. Felton (1997) allowed public funds to pay the salaries of public school teachers educating economically disadvantaged children, including private religious schools. This landmark ruling reversed Aguilar v. Felton (1985), which held that paying public school teachers to teach parochial school students was “excessive entanglement” with religion. Agostini reversed that decision and determined the program was neutral with respect to religion and that the purpose of educating disadvantaged children was a secular one.

Deference to religious neutrality flows down to the state courts as well.

Florida cases such as Koerner v. Borck (1958) argued that, “State power is no more to be used so as to handicap religions, than it is to favor them.”

Meanwhile, in Johnson v. Presbyterian Homes of Synod of Florida, Inc. (1970), the Florida Supreme Court ruled on a tax exemption:

“A state cannot pass a law to aid one religion or all religions, but state action to promote the general welfare of society, apart from any religious considerations, is valid, even though religious interests may be indirectly benefited.”

Espinoza isn’t deviating from the U.S.’s “separation of church and state,” as critics have misunderstood. The ruling follows a long history of allowing religious institutions and persons to benefit from public programs, in this instance extending that right to K-12 education where powerful opponents attempted to carve out an exemption.

A fight over how much religion can be taught in a private school may be around the corner. But that is a fight for another day.

Kendra Espinoza of Kalispell, Montana, lead plaintiff in the case, with her daughters Naomi and Sarah outside the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., in January.

In a landmark decision today on school choice, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Montana Department of Revenue’s shutdown of a tax-credit scholarship program for low-income students is unconstitutional, potentially opening the door for states to enact such programs for students to attend private faith-based schools.

The court said in its 5-4 decision on Espinoza vs. the Montana Department of Revenue, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, that the Montana Department of Revenue cannot disqualify religious schools simply because of what they are.

“A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious,” the opinion said.

The ruling also stated:

“Drawing on ‘enduring American tradition,’ we have long recognized the rights of parents to direct ‘the religious upbringing’ of their children … Many parents exercise that right by sending their children to religious schools, a choice protected by the Constitution.”

Roberts was joined by Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch. Dissenting were Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer.

“The Supreme Court delivered a major victory to parents who want to choose the best school for their children, including religious schools,” said Institute for Justice senior attorney Erica Smith, who was co-counsel on the case. “This is a landmark case in education that will allow states across the country to enact educational choice programs that give parents maximum educational options.”

Organizations that support education choice praised the decision.

“It’s a good news day for those who love the freedoms we enjoy in this country and seek to advance and preserve those freedoms,” said Leslie Hiner, leader of the Legal Defense & Education Center for the nonprofit advocacy group EdChoice. “Today the Supreme Court has re-affirmed its role as the guardians of our Constitution. The Montana Supreme Court has disregarded the U.S. Constitution, and in particular the First Amendment’s clause protecting our right to the Free Exercise of whatever faith we choose as individuals, when it struck down a modest school choice program that allowed parents to choose any school, religiously-affiliated or not, for their children’s education.”

The case started in 2015, when the Montana Legislature enacted a program that provided a dollar-for-dollar tax credit for taxpayers who donated to a Student Scholarship Organization. That meant a Montana resident could donate to a scholar organization, and in turn, would receive a tax credit for the donation.

The Student Scholarship Organization used the donated money to provide scholarships to students to attend private schools, including private schools affiliated with a religion.

Shortly after the program was enacted, the Montana Department of Revenue promulgated an administrative rule (“Rule 1”) prohibiting scholarship recipients from using their scholarships at religious schools, citing a provision of the state constitution that prohibits “direct or indirect” public funding of religiously affiliated educational programs.

Kendra Espinoza and the two other mothers filed a lawsuit in state court challenging the rule. The trial court determined that the scholarship program was constitutional without the rule and granted the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment. On appeal, the Department of Revenue argued that the program is unconstitutional without Rule 1. The Montana Supreme Court agreed with the Department and reversed the lower court.

At issue in the case are Blaine Amendments, also called “No Aid” clauses, which are provisions in 38 state constitutions, including Florida’s, that bar public aid to religious organizations. They get their name from James G. Blaine, a congressional representative and later senator and presidential nominee from Maine who unsuccessfully attempted to amend the U.S. constitution in 1875 to include “anti-aid” language onto the end of the first amendment. Where he failed at the federal level, many states inserted Blaine Amendments into their constitutions. As a result, Blaine Amendments frequently act as state-level barriers against school choice.

“I am thrilled that the courts ruled in favor of the Constitution and maintained a parent’s right to choose where their children go to school,” Espinoza said in a news release issued by the Institute for Justice. “For our family, this means we can continue to receive assistance that is a lifeline to our ability to stay at Stillwater. For so many other families across America, this will potentially mean changing lives and positively altering the future of thousands of children nationwide. What a wonderful victory.”

The win and the promise of continued scholarships is a significant boost to Espinoza, who has had to work multiple jobs, including cleaning houses and doing janitorial work, to afford her daughters’ tuition payments at a private Christian school in Kalispell. Kendra transferred her two daughters to Stillwater Christian School after they struggled in their public school. Montana’s scholarship program has helped Kendra and families across the state keep their children in the school that works best for them.

“It’s been a century-and-a-half since the bigoted Blaine movement took root in state constitutions throughout the country,” IJ Senior Attorney Richard Komer, who argued the case before the Court said in the news release. “Today’s decision shows that it is never too late to correct an injustice, even one with as long and ignoble a pedigree as this one.”

Today’s decision will affect most of the 14 states that have strictly interpreted their state constitution Blaine Amendments to bar scholarships to children at religious schools. For decades, the creation and expansion of school choice programs have been inhibited by legislative concerns that they might conflict with state constitutions. Those concerns are now removed with today’s decision in Espinoza.