Christopher Bermudez and Peyton Ecklund, both 17, engage in a classroom-based citizen science project at BioTECH High in Miami. The school allows students to pursue authentic scientific research studies that may result in publication in peer-reviewed scientific journals and presentations at local, national and international conferences. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

MIAMI – Christopher Bermudez likes plants. Like, really likes plants. The thought of reviving a droopy sprig of mizuna inspired the 17-year-old to riff: “When you kind of have faith in the plants, and you keep taking care of it, and you see it spring back up to life, that’s one of the biggest fulfilling feelings ever.”

How gratifying for Bermudez that he gets to pair that infatuation with real-world research. Among other projects, he and his classmates at BioTECH High School are helping scientists with a mammoth, years-long venture to determine which cultivars of edible plants will make the best crops for – no joke – space travel.

“Our research helps supplement their research,” said Bermudez, who’s aiming for a career in experimental horticulture. “You’re kind of helping the future of our species.”

BioTECH and its lovable science geeks make for a compelling narrative. So does the back story.

First pan to Florida, which has expanded charter schools, private school scholarships, education savings accounts and other varieties of educational choice as much as any state in America. Then zoom in to Miami-Dade County, home to a forward-thinking school district that chose to surf this “tsunami of choice” rather than fight it. The result is a rich, evolving, educational ecosystem where a slew of new educational cultivars are vying to find their niches.

If the theory holds, ever more students will choose from ever more options – including district choice options like BioTECH – to find the one that fits their needs and fuels their passions.

Daniel Mateo is principal at BioTECH High, the nation's only high school specializing in conservation biology. To hear an interview with Mateo, click on the video link at the end of this story. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

“Choice is very important in human nature, right? And I think that for students, choice is of utmost importance,” said BioTECH principal Daniel Mateo, a chemist by training. “When you force a child to do something, it never really works out quite the way you think it’s going to work out. But when you give them the flexibility of choice, you allow them to select what it is they want to do based on that natural affinity that they have for that particular subject. It’s a given. They’re going to perform.”

BioTECH, all of five years old, is a magnet school and the nation’s only high school specializing in conservation biology. Its aim: to develop successive generations of researchers who will apply their ingenuity and training to the conservation of life on Earth.

Heady stuff. Which makes it all the more remarkable, maybe, that BioTECH has no entrance requirements; serves a student body that is mostly low-income; and shares a campus with a once-struggling middle school.

Richmond Heights Middle, 14 miles southwest of gleaming downtown Miami, was perpetually C-rated by the state. Over the years, scores of school choice options mushroomed around it – and parents responded accordingly. Enrollment fell by half.

In turn, the Miami-Dade school district responded accordingly. It considered what academic programming students and parents wanted; what college degrees and jobs were hot; what community partnerships it could forge or strengthen. With help from a $10 million federal magnet schools grant, BioTECH was born.

The middle school is home base. But BioTECH’s 400 students spend big chunks of time doing research at three partner institutions: Zoo Miami, Everglades National Park and Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. Their lab equipment is college-caliber. Half their teachers are working scientists. They’re expected to shoot for publication in a scientific journal by the time they graduate.

Andrea Medina, 17, a senior at BioTECH High, wants to pursue a career in the medical field when she graduates from college. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

Some of BioTECH’s “junior scientists” are studying the intestinal flora of spider monkeys to develop diets that make captive monkeys less prone to stomach problems. Others, like Bermudez, are doing research for Growing Beyond Earth, a partnership between Fairchild and NASA. Still others work in micropropagation labs at Fairchild, growing rare orchids that can be reintroduced into slices of South Florida where they once thrived.

“Who thought plants could be so fun?” said senior Peyton Ecklund.

Ecklund, 17, who plans to pursue botanical research in college, chose BioTECH over other high-performing schools in Miami-Dade. She liked that it was “trying to do something special” and emphasized student-driven learning. “We have to make the projects from scratch. And we have to figure out what works and what doesn’t,” she said. “If you learn how to be independent and figure it out on your own now, who knows what you can do in the future?”

Judging by demand, BioTECH is a smash. Last year, it reeled in 600 applications for 150 seats. So far this year, it’s on pace for 1,000 applications for 100 seats.

It’s no surprise the school took root in Miami. Miami-Dade has the highest rate of charter school and private school students of any urban district in Florida. It has one of the highest rates of students exercising district choice. More than 60 percent of Miami-Dade students are now enrolled in hundreds of district options, from magnet schools and career academies to international programs and K-8 centers.

“We recognized … the choice tsunami was upon us,” Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said in April. “And I was not going to do what lot of my colleagues did. Which is, ‘Let’s hope and pray it doesn’t hit us.’ “

BioTECH earned an A from the state this year. (Richmond Heights earned a B.) Its demographics mirror the district’s. Eighty-nine percent of its students are non-white (it’s 93 percent for the district). Sixty-three percent are eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch (it’s 66 percent for the district). Forty-two percent, meanwhile, receive special education services or accommodations.

“That’s 100 percent by design,” Mateo said. “It’s not about having elite students … If you have a passion (for science), we can cultivate that.”

The district does not provide transportation to BioTECH. That’s not a plus for equity. But HVAC repairmen and nursing assistants find a way to get their kids there just like radiologists and military officers do.

Daniella Lira, 17, a junior at BioTECH, said her parents left poverty in Peru for a better life in the U.S. A love for animals and a desire to be a veterinarian led her to the school. Diving into hands-on science has her considering other possibilities.

“Being part of the research and being treated as an actual scientist has opened my eyes,” Lira said.

BioTECH should open some eyes, too. There’s no end to the variety that can sprout in choice-rich soil.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDmOT7P-Aso&feature=youtu.be

Former public school teacher Nadia Hionides has successfully melded the anti-establishment views of her youth with her passion for empowering families to make the best educational choices for their children.

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. – First day of school. Pick-up time. As 375 giddy students clotted in The Foundation Academy courtyard, Nadia Hionides, the K-12 school’s founder and principal, made the rounds. She asked returning students how their summers went. She asked the new ones if they made new friends yet.

One girl toggled from cheerful and chatty to turning her head and staring, expressionless, as if listening for something in the distance. Another girl curled her lips into a tight smile as eyes cloaked by mascara locked with Ms. Nadia’s. The girl’s mom enrolled her because bipolar disorder necessitated a learning environment that was less rigid, more patient. Hionides talked most with a shy but smiley new girl, connected via tubes to an oxygen tank. At her prior school, the girl had been placed in a class with a wide range of special needs – and, in her parents’ view, not challenged academically. That won’t happen here, Hionides said.

“Some kids take a little more work, some take a little more time,” she said. “But here they feel like they belong.”

Half-hidden in Florida’s pruned-palm sprawl, the 32-year-old Foundation Academy bloomed organically from Hionides’s convictions about teaching and learning.

Nadia Hionides: Educational choice is "a rebellion."

A former public school teacher, Hionides, 66, was repulsed by the dictates, the labeling, the testing, the tracking. She aimed to create a school for “gifted kids,” heavy on inquiry and arts and community service, that was accessible to all kids. With a big assist from Florida’s assortment of educational choice scholarships, that’s what happened.

The Foundation Academy sits on 23 acres buffered by pines. It’s intentionally and voluntarily diverse. Forty percent of its students have been diagnosed with “disabilities.” Fifty-four percent are non-white. Eighty-six percent use state educational choice scholarships, predominantly the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income students (administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog) and the McKay Scholarship for students with disabilities.

Too many disadvantaged students “don’t get art, they don’t get to go on field trips, they don’t get to do all these STEM things,” Hionides said. “We give them the same enrichment. We give them the same privileges. It’s called equity and justice.”

If those sound like progressive buzzwords, they are. Fifty years ago, Hionides, a self-described “hippie from New York, man,” was chanting “power to the people,” fist up, to protest the Vietnam War. Now she’s preaching “power to the people” to expand educational options. She sees a direct link between the anti-establishment views of her youth, and the values that guide her take on public education.

“It’s a rebellion,” she said of educational choice. “You are empowering yourself to make the choice for your child. You’re not bowing down to the man. This money is now your opportunity.”

“I grew up in an era where you said, ‘We’re going to stick it to the man,’ “ Hionides said. Educational choice “is a continuation of that era.”

The Foundation Academy revels in non-conformity.

Its website says it was “founded on Christ’s values of faith, hope, and love.” It holds Bible study every morning. But there are also Tai Chi classes; a deep immersion in the arts, particularly theater; and an environmental consciousness that manifests itself in an organic garden, a solar-powered aquaponic farm and a “Three R’s” class where students re-use, repair and recycle things like old furniture. The crosses on the walls can’t be missed. Neither can the piano guts hanging as artwork, the abstract sculpture that graces the front of the school, the John Deere tractor out back.

All of it serves a purpose. “Kids generally feel like misfits,” Hionides said in a 2016 interview. “But when they come to The Foundation Academy, they see everyone’s a misfit.”

Purple hair? No prob. Nose ring? Do you. Diversity, respect, acceptance, affirmation – all are core to The Foundation Academy culture. Over the years, the school has also served dozens of openly LGBTQ students, including some who were bullied relentlessly in their prior public schools.

Success here is not defined by test scores. The most recent testing analysis of tax credit scholarship schools shows academy students falling three percentile points in reading and math relative to students nationally. Hionides said it’s because the school puts zero value on standardized tests – and makes no bones about it. (A growing body of evidence supports her skepticism.)

Learning at The Foundation Academy is assessed through presentations, projects, portfolios. Six years ago, Hionides started the Jacksonville Science Festival to spur more students in more schools to learn through inquiry projects. It began with 1,500 students. It’s grown to 4,000.

Hionides makes a point of being visible and showing students she cares. “Kids generally feel like misfits,” she said in a 2016 interview. “But when they come to The Foundation Academy, they see everyone’s a misfit.”

The Foundation Academy is inspiring teachers too. A half-dozen of its 40 staffers are former public school teachers, including Courtney Amaro, a 10-year veteran who’s been at the school seven years. She stumbled on it when she took students from her prior school to the science festival. She saw kids like the ones she was teaching – low-income, mostly minority – making poised presentations on head-spinning subjects. “The light bulb went on,” Amaro said.

Two months later, she joined the rebellion.

The rebel leader won’t fit into anybody’s box either. Hionides is a Democrat. She voted for Bernie in 2016. But she often votes Republican in general elections because she can’t stand how Democratic leaders have demagogued educational choice.

Hionides’s parents immigrated from Egypt to New York when she was seven. (She’s of Greek, Lebanese and Cypriot descent.) Her father got a job at his brother’s fish meal business. She and her siblings attended public schools. She did well, she said, except on standardized tests. When she got accepted into college despite less-than-stellar test scores, “I kissed the floor.” She went on to earn a master’s in education from the University of Pennsylvania.

She taught in an inner-city elementary school. In a state-supported boarding school for students out of chances. In a center for adults with mental health issues. In all, she emphasized project-based learning. Her students loved it. Her administrators didn’t. “It wasn’t black and white, it wasn’t kids sitting in a row, it wasn’t teachers standing up in front of the class,” she said.

Hionides and her husband moved to Jacksonville in 1982. She started The Foundation Academy six years later. In the office of her family’s motel, she taught her daughter, her daughter’s friend and the sister of her daughter’s violin teacher. The latter was a “hellion,” bright but prone to bad decisions … like doing donuts on an ex-boyfriend’s lawn. The violin teacher “said please, please, please, can you help my sister?” Hionides said. “I said, ‘Why not’?”

The Foundation Academy grew from there.

In Florida’s rich environment for educational choice, Hionides said, there’s nothing to stop other educators from doing and growing their own thing too. Teachers who feel crushed in their current schools should start their own, she said.

And stick it to the man.

To hear more from Hionides about educators starting their own schools, click on the audio file below.

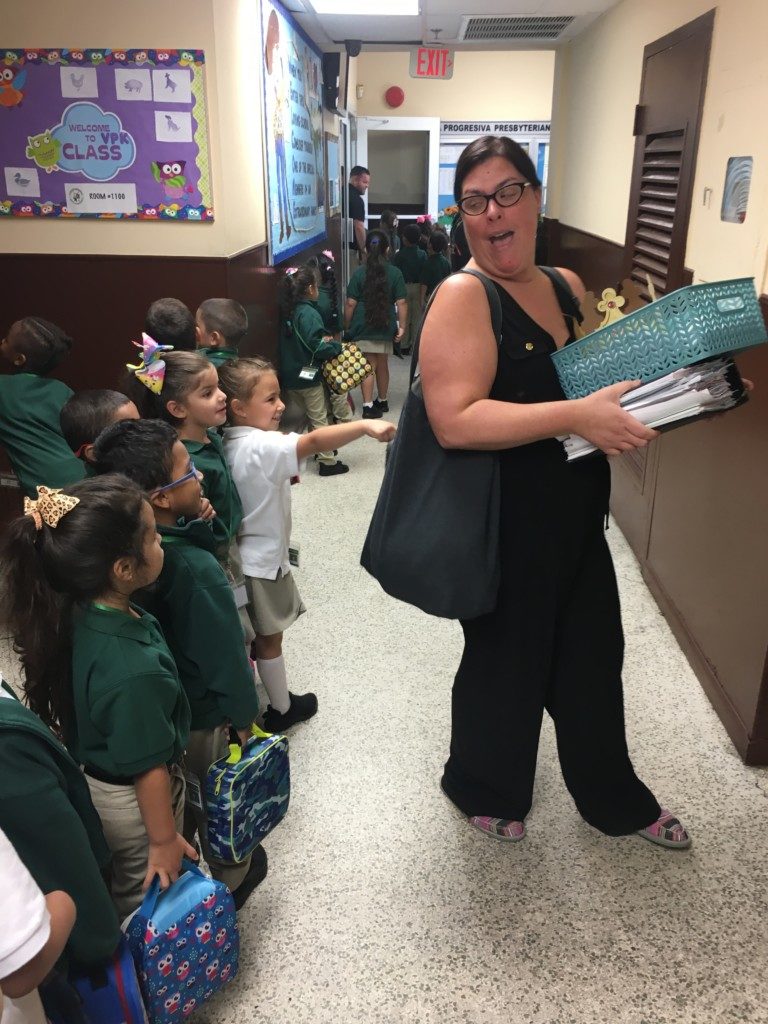

Melissa Rego, principal of La Progresiva Presbyterian School in Miami, has 18 years of experience in district, charter and private schools. When she assumed the helm of La Progresiva a decade ago, it had 162 students in K-12. Now it has 673-- all of them with school choice scholarships.

MIAMI – Little Havana is in a hurry. Long before dawn bathes the palms in soft light, thousands of workers stream from neighborhoods where modest homes are tucked in tight as pastelitos in a Cuban bakery. Ignition. Traction. Acceleration. Past the store fronts with the proud Latin names. Past used car lots studded with American flags. Past the restaurant walk-up windows where smooth, sweet cortaditos pump fuel into true believers.

In the thick of this working-class hum is a faith-based school once harassed by Fidel Castro. He couldn’t kill La Progresiva Presybterian. Neither could the teachers union. Now it’s thriving more than ever.

How fitting that it’s led by a former public school teacher who’s the daughter of exiles.

How fitting that it’s led by a former public school teacher who’s the daughter of exiles.

Melissa Rego grew up four blocks from La Progresiva, the second child of a bank teller and a car mechanic. When she became principal a decade ago, the school with vanilla paint and Cuban roots had 162 students in K-12. Now it has 673 – all with state-backed school choice scholarships for lower-income students.*

The director who hired Rego told her to do whatever it takes to propel the school to its potential. So the woman with 1,000 facial gestures behind horn-rimmed glasses became Inspirer-in-Chief. Over and over, she reminds the sons and daughters of cooks and waitresses and gas station attendants what Little Havana teaches them every day. They know it in their bones, but still can’t hear it enough from somebody who’s been-there-done-that.

“More than anything, it was speaking life into these kids,” Rego said. “Battling with these kids about the thoughts they have, that they can’t accomplish anything. We told them, ‘You have the ability to do this. We’re going to equip you. You have a future. But you have to grind. You have to work like a dog. Things are not going to fall out of the sky for you.’ ”

Florida is home to arguably the most diverse array of school choice in America. The pluses for students and parents are well established. But choice is helping educators, too. More and more (see here, here, here, here) are able to work in, lead, and even create educational options that are in line with their talents, visions and values. In a world where choice is still “controversial,” they are trail blazers.

Rego, 42, didn’t set out to be one. She graduated from public school in Miami, got a full ride to Miami-Dade College, earned a bachelor’s in health science from the University of Miami. (Later, she earned a master’s in educational leadership from Nova Southeastern.) Her teaching career began 18 years ago. She started as a sub in the Miami-Dade district, working with emotionally disturbed students, then taught four years at a career academy high school. At the invitation of a friend who had become a principal, she headed to a new charter school.

The charter was serving 600 middle school students … in a movie theater. Its intended building wasn’t completed on time, so the school had to wing it.

That it did, successfully, helped Rego understand the power of school choice. (more…)

Teaching customized to the developmental needs of each child has been the dream of K-12 educators for over a hundred years. When I was in graduate school in the 1970s, we talked continuously about the need to abandon the one-size-fits-all, assembly-line instruction that permeated public education. But we didn’t know how to translate our ivory-tower talk about customization into real-world action.

We know education choice is a necessary but not sufficient condition for achieving excellence and equity in public education. Our goal is for every child to have access to effective, efficient customized instruction in schools, at home and in their communities. Choice is a pitstop on the road to customization.

In the early 1990s, I was a teacher union representative on a statewide commission studying how to improve Florida’s public education system. We proposed reorganizing the system around standards-based, customized instruction, but quickly abandoned the idea after teachers across the state rebelled at a series of public hearings. The teachers said we were naïve and out of touch with classroom realities. While their language may have been a bit harsh, they were correct. Our proposals were impractical. In 1992, public education was still not prepared to meet the unique needs of each child.

Thanks to emerging new technologies and policies, perhaps that time has come. Public education may finally be ready to implement customized instruction in ways that weren’t possible in earlier eras. The inability to scale has historically been the downfall of progressive efforts to move beyond one-size-fits-all instruction. In a country with 56 million PreK-12 students, instructional methods that are highly effective but not scalable have little systemic impact. A good example is Montessori programs. Many students would benefit if they had access to Montessori-based instruction. The first Montessori school opened over 100 years ago and yet, as of 2013, only about 125,000 US public school students were enrolled in Montessori programs. (more…)

We thought redefinED readers would enjoy the following essay about Florida's Personal Learning Scholarship Account by Tampa, Fla. parent Mary Kurnik. It originally appeared in the summer 2015 issue of The Old Schoolhouse magazine, and is re-published with the magazine’s permission.

The PLSA is an education savings account (ESA) administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog. The essay notes only Florida and Arizona have ESAs, which was true when Kurnik submitted the piece last spring. Since then, three more states have adopted ESAs, including Nevada, which created a program that is available to more than 90 percent of its students.

By Mary Kurnik

“. . . weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning” (Psalm 30:5).

Dealing with special needs is a family journey, not limited to the child with the diagnosis. My son has unique abilities and learns differently. He happens to have autism.

For years prior to the diagnosis, we were perplexed by John’s speech patterns, motor skills, inflexibility with daily life, and adverse reactions to bright lights, loud noises, and large crowds. During those years, John had testing and therapies, but those were done on a careful schedule and budget. Often late at night, after our children were asleep, my husband and I shed tears over how we would manage to meet John’s short- and long-term needs as prescribed by his doctors. (more…)

The annual American Federation for Children conference is one of the country’s largest gatherings of school choice advocates. So it was notable, during the most recent conference in Orlando, that speakers regularly used the terms “parental choice” and “educational choice,” but not “school choice.”

The annual American Federation for Children conference is one of the country’s largest gatherings of school choice advocates. So it was notable, during the most recent conference in Orlando, that speakers regularly used the terms “parental choice” and “educational choice,” but not “school choice.”

This shift in semantics reflects an emerging trend that’s a game changer – the expansion of choice in publicly-funded education is increasingly including learning options beyond schools.

Florida’s new Personal Learning Scholarship Account program, for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome, is a good example. In the PLSA program, public funds go into a bank account that parents can use for numerous state-approved educational options, including private school tuition, a suite of different therapies, curriculum materials, instructional technology, and postsecondary education and training.

This ability to use public funds to pay for learning options beyond schools allows parents to customize an education that is most appropriate for their child. To that end, there’s no doubt that in coming years, parent-controlled educational spending accounts will become more and more common. This shift from state control of education funds to parental control, combined with the movement toward customized teaching and learning, is going to revolutionize public education.

It’s also going to complicate many of our current education reform debates, and maybe make some of them moot.

For example, our current regulatory accountability systems assume students receive instruction from a single provider. But increasingly, parents are using public education funds to access instruction from a variety of providers at the same time. So, to take one hypothetical, future example, how do we assign school grades when children are simultaneously receiving instruction from a charter school, a virtual school, a magnet school and a personal trainer? When four instructional providers contribute to a child’s yearly learning gains, accurately assigning responsibility to each provider is challenging.

This same challenge extends to using yearly standardized test scores to evaluate teachers. If a child receives language arts instruction from several teachers over a 12-month period, which teacher should be held accountable for this student’s standardized test score in language arts?

Our current testing debate also feels dated. (more…)

One parent told us it was a blessing. Another said it was like winning the lottery. Another said she and her son, an eighth-grader with autism, had “finally won.”

Today marks the start of a new K-12 scholarship program in Florida and maybe even a new era in parental choice – a shift from simply giving parents the power to choose from amongst schools to something more personal and far-reaching. The early reaction from parents suggests it couldn’t have happened soon enough, and to a more deserving group.

Today marks the start of a new K-12 scholarship program in Florida and maybe even a new era in parental choice – a shift from simply giving parents the power to choose from amongst schools to something more personal and far-reaching. The early reaction from parents suggests it couldn’t have happened soon enough, and to a more deserving group.

“This scholarship will make all the difference in the world,” said Dorothy Famiano of Brooksville, who has two eligible children – Nicholas, who has Spina bifida, and Danielle, who has been diagnosed with autism.

Starting at 9 a.m., Famiano and other parents of children with significant special needs including autism, Down syndrome and cerebral palsy can apply for Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts. PLSAs will allow parents to use the money to choose from a variety of educational options – not just tuition and fees at private schools, but therapists, specialists, tutors, curricula and materials, even contributions to a prepaid college fund.

The program reflects the obvious benefits of tailoring a child’s education to his or her specific needs; the explosion in educational options that makes customization more possible and fine-tuned; and the sensibility of giving parents the power to make those choices. But don’t take our word for it.

Michele Kaplan of Coral Gables said a scholarship account will be a game changer for her son, Matthew, 9, who has a dual diagnosis of autism and Fragile X syndrome. (more…)

Imagine if parents could pick and choose individual courses for their children, from an endless array of different providers, in the same way they now pick and choose other products online. Michael Brickman, the national policy analyst for the Fordham Institute, says that world may not too far in the future, thanks to a budding parental choice trend folks are calling “course choice.”

“Ideally parents and students can sit down at the computer and "shop" online for courses,” Brickman said during a live chat Wednesday with redefinED. “This is so commonplace and mundane when we go on sites like Amazon.com and add items from different sellers from around the world to our virtual shopping cart. Hopefully through (course choice), education can catch up to the rest of the world in this regard.”

A handful of states are moving ahead with course choice, including Louisiana and Wisconsin, where Brickman served as a policy advisor in Gov. Scott Walker’s office before joining Fordham. Florida is among those taking a close look. Brickman recently authored a policy brief that gives education officials a primer on course choice and the challenges ahead.

Course choice is complementary to parental choice options such as charter schools and vouchers, he said during the chat. But it can spur those options to innovate even more.

“I love traditional school choice and think it's nowhere near obsolete as of now,” he said in response to a question. “But one of the frustrating things about these reforms is how similar the schools look to one another. The point of additional flexibility is to INNOVATE. Some charter and private models are off and running with this but many are still lining up 30 desks in each room, putting a teacher in front of the class for 7 hours a day, etc.”

You can read the entirety of the chat in the transcript below.

Don’t look now, but a bigger, faster and potentially more far-reaching wave of educational choice is rolling in as we're still grappling with basic questions about vouchers, tax credit scholarships and charter schools. Lucky for us, a new guide from the Fordham Institute offers a heads up on the complications with “course choice” so its promise can be fully realized.

Released today and authored by Michael Brickman, Fordham’s national policy director, “Expanding the Education Universe: A Fifty-State Strategy for Course Choice” arrives as school choice begins to give way to educational choice on a more fundamental level.

“Rather than asking kids in need of a better shake to change homes, forsake their friends, or take long bus rides, course choice enables them to learn from the best teachers in the state or nation,” Brickman writes. “And it grants them access to an array of course offerings that no one school can realistically gather under its roof.”

To some extent, course choice is already happening. Students in many places can take dual enrollment courses. Florida offers a vast course menu through Florida Virtual School. Louisiana adopted a course choice program two years ago. It’s just a matter of time before other states and/or school districts seize the day in a bigger way, and some, like Florida, are already taking a closer look.

The bottom line: students will increasingly be able to choose a course here and a course there, from an exploding number of providers. That will increasingly be true no matter what school they’re in.

That’s the upside. The downside? All kind of prickly questions have to be tangled with, from funding and access to eligibility and accountability. Brickman offers a rundown of five big ones, with potential directions, complications, tensions and tradeoffs. For example:

Who can be a provider: “Parents and kids will naturally want the widest possible range. Districts, however, will tend to favor tighter limits, whether out of concern for quality control or to minimize competition with their own offerings. States will also have to balance the desire to serve more children with the political headache that inevitably comes when ‘controversial’ course providers are included. Or they may leave such decisions to districts or entrust them to third parties.”

Who pays them: “Does the child’s school district pay the cost? Does the state? The parents? Who decides what price is reasonable? How many kids can take how many such courses? Who controls this money? Who generates it?”

Then there’s this fun one: “What if Molly takes all but one or two of her courses from course providers? Is she still a student of Madison High School? Does it still confer her diploma? Is it still the school’s job to determine whether she has truly fulfilled state or district graduation requirements? If not the school, then who?”

And some thought school choice was complicated. 🙂