DAVENPORT, Fla. – Valeria Oquendo didn’t set out to be an entrepreneur. “Ms. V,” as her students call her, had wanted to be a teacher since she was a teenager. On her way to an elementary education degree, she interned at a public school and, initially, those dreams became even clearer.

“Still in my brain I was thinking, ‘I’m going to graduate, I’m going to have my perfect classroom, I’m going to be a first grade teacher,’ “she said.

But then, in education-choice-rich Florida, a funny thing happened.

Oquendo’s “side hustle” became her full-time gig.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, friends and family begged Oquendo to tutor their children, many of whom were struggling with online instruction. Oquendo was still in college. But before she knew it, she was tutoring 20 kids.

The light bulb flickered on.

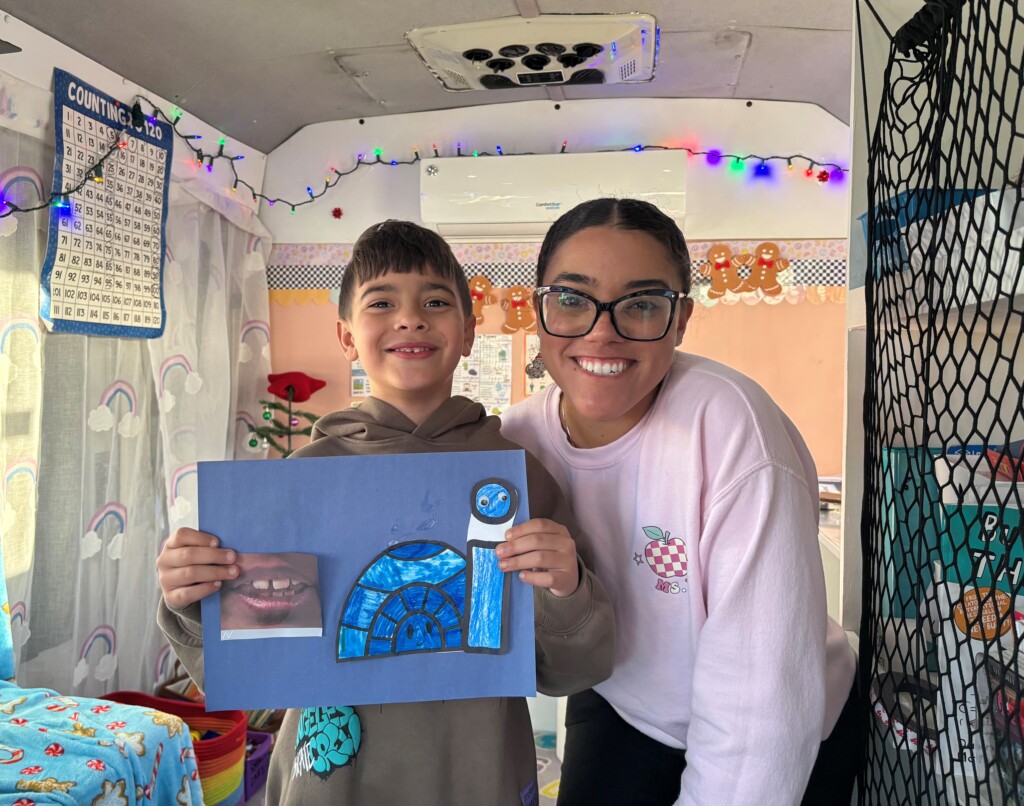

Today, Oquendo runs Start Bright Tutoring, a mobile tutor and a la carte education provider in this insanely fast-growing corner of metro Orlando.

She focuses on elementary reading and math, with 20 to 30 students who are homeschooled or in public schools. A handful use state-supported education savings accounts (ESAs), and it’s highly likely even more will use them in the future.

Demand is soaring. When Oquendo pitched her business on TikTok, mayhem ensued: She racked up hundreds of thousands of views and put 70 students on a wait list before being forced to stop taking calls.

Now Oquendo sees a future outside of traditional schools not only for herself, but for other young educators. As choice continues to expand, she said, more and more can tap into the new possibilities.

“Everybody has their niche,” said Oquendo, 26. “It all depends on the effort and not giving up.”

Florida is humming with former public school teachers who, thanks to choice, have created their own learning models. Their often-inspiring stories (like this and this and this) are becoming commonplace.

Oquendo, though, is the next wave: Educators creating their own options instead of becoming traditional public school teachers.

Oquendo represents a couple of other fascinating trend lines, too.

She’s a niche provider instead of a school, which allows her to serve Florida’s fastest-growing choice contingent: a la carte learners.

Florida has multiple ESA programs that give families flexibility to pursue options beyond schools. With ESAs, they can choose from an ever-growing menu of providers, like Start Bright, to assemble the program they want. The main vehicle for doing that, the Personalized Education Program scholarship, met its state cap of 60,000 students this year, up from 20,000 last year.

Oquendo’s decision to create an option on wheels is also noteworthy.

Florida’s education landscape gets more diverse and dynamic every day. But it’s still rife with frustrating stories about talented teachers trying to set up microschools and other innovative models, only to run into outdated zoning and building codes and/or code enforcers who seem to be curiously inflexible. (Thankfully, some still find happy endings.)

Until those barriers are addressed, going mobile – something choice visionaries suggested nearly 50 years ago – may be one way out.

Oquendo is the daughter of a police officer and an accountant. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, the family moved to Florida, and she enrolled in the University of Central Florida.

Oquendo said she was fortunate to have an amazing teacher as her mentor when she interned at a public school. But she was also haunted by the moment the teacher told her the class needed to move on to the next unit of study, even though several students, including one with a learning disability and another learning English, were not ready.

“She said, ‘This is what we do.’ “Translation: We have to move on.

That experience pushed Oquendo to choose a different path, too.

Initially she wanted to steer her tutoring venture into a microschool. She found a good location, but the building needed $15,000 in adjustments to meet building codes, and even then, there was no guarantee of a green light from local officials. Oquendo was bummed. Thankfully, her mom came to the rescue, inspired by a mobile grooming service the family uses for its Schnauzers.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you get a van and make it a mobile classroom?” Oquendo said. “I was like, ‘Mom, the kids are not pets.’ “

Upon further investigation, mom was on to something. In the summer of 2021, Oquendo spent $8,000 for a 2014 Ford E-350 shuttle bus, then another $7,000 to turn it into a mini-classroom. Ms. V’s van is complete with desks, bins, lights, shelves, computers – and just about anything else you’d find in a typical classroom.

That fall, Oquendo was up and running, visiting students in their homes. At some point, she realized she could reach more families if she parked at locations that were still convenient – like shopping plazas – and have them meet her there.

Oquendo’s TikToks came just months after she earned her degree. The response was understandable, she said, given that many families lived the same reality she witnessed as an intern.

“It’s the system,” she said. “If it was better, we wouldn’t have the demand.”

Oquendo said many families also respond to her because they share a cultural connection. She was still struggling with English when her family moved to Florida, and many of her students are English language learners, too. She offers living proof they will overcome.

“I tell them, ‘I get you,’ “she said. “I tell them, ‘It’s okay to make mistakes. I love mistakes.’ That way, they’re not afraid.”

Forging her own path has not been all peaches and cream.

At one point, the van engine died, and Oquendo had to find $6,000 to replace it. At another, she invested in solar panels, hoping to cut down on fuel costs for air conditioning. But they didn’t work as she hoped. “I didn’t have a guide,” she said. “I just had myself – and my mistakes.”

At the same time, she said, she takes satisfaction in knowing her students are making progress. And that she has the power to quickly adjust, both for them and herself.

Oquendo is shifting to serve more students whose parents want in-home tutoring for longer stretches. She’s adding Spanish lessons. She’s also offering monthly field trips to places like LEGOLAND and a local farm.

On a whim, Oquendo recently set up gardening lessons for interested families, essentially sub-contracting with an organic farmer. Her students loved it.

In South Florida, similar operators are realizing they fit into changing definitions of teaching and learning and becoming ESA providers themselves.

Oquendo said the challenges to doing her own thing are real. But the freedom to control her own destiny, and to better help students in the process, makes it all worth it.

“I feel happy, blessed, and fortunate to be doing what I love the most,” she said.

Microschools have been having a moment, garnering positive headlines in the Christian Science Monitor, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post and other mainstream outlets. They're one of the hottest topics on social media and the education conference circuit.

So it's no surprise the inevitable backlash is brewing.

Before we get into it, I'd like to make one stipulation. The term "microschools" defies tidy definitions.

Often, but not always, microschools are smaller than typical learning environments. Often, but not always, they operate outside the aegis of the public school system. Sometimes, but not always, they rely on adults who don't hold traditional teaching credentials. Sometimes, but not always, they blur the lines between schooling and homeschooling, hosting students around living room tables or on farms or in the woods.

Two different people may use the term microschool and have completely different learning environments in mind. Neither would necessarily be wrong.

Now for the backlash, via education blogger Peter Greene.

When someone asks hard critiques like "This voucher you're offering me won't cover the cost of any private school" or "When this voucher program guts public school funding, families in our rural area will have no choices at all" then microschools are the handy choicer answer.

Can't get your kid into a nice private school with your voucher? Well, you can still pool resources with a couple of neighbors, buy some hardware, license some software, and start your own microschool! Microschools allow choicers to argue that nobody will be left behind in a choice landscape, that vouchers will not simply be an education entitlement for the wealthy. (Spoiler alert: the wealthy will not be pulling their children out of private schools so they can microschool instead).

In other words, microschools do not solve any educational problems. They solve a policy argument problem. They do not offer new and better ways to educate children. They offer new ways to argue in favor of vouchers. Well, all that and they also offer a way for edupreneurs to cash in on the education privatization movement.

Greene is right about one thing. Often, but not always, microschools aren't competing with elite private schools. It's a safe bet that most parents shelling out upwards of $30,000 a year for tuition are not about to abandon their exclusive cloisters for a repurposed farmhouse that charges a few hundred bucks per month. Recent reports by the VELA Education Fund on community-created learning environments (which sometimes, but not always, take the form of microschools) and the National Microschooling Center suggest that the typical microschool family is decidedly middle class. These are families who could never contemplate the likes Andover or Gulliver Prep. They might be able to scrape together modest tuition payments, but an $8,000-per-year scholarship could make a big difference in what they can afford.

I'm on the record as a pre-pandemic microschool enthusiast and spent time during the pandemic studying learning pods (which often, but not always, shared many features with microschools). So, I'd like to offer a response to Greene's question, which recalls the technological skepticism of Neil Postman: What is the problem to which microschools are the solution? And whose problem is it?

For pandemic pods, the answer was simple. Schools shut down, and families needed a place their kids could go.

But many families discovered other benefits they weren't getting in conventional schools. Teachers could be more flexible with their time, and therefore, more responsive to the needs of their students. Students enjoyed more humane learning environments in big and small ways. Children with disabilities received more individual attention. Students could freely grab a snack when they wanted. Community assets, from the neighbor with a knack for carpentry to the museums and community groups previously confined to afterschool programs, could play a more central part in the schooling experience. Adults from more diverse backgrounds, like parents or community volunteers who loved working with kids but lacked a teaching certificate, found new opportunities to share their passions. And the small size allowed for a far wider array of diverse options catering to families' unique preferences than were typically possible.

Many parents abandoned their podding experiences once schools reopened. Conventional schools still offered countless advantages (a large and diverse group of peers, guaranteed childcare outside the home, reliable special education services, no out-of-pocket costs).

But other families latched on to the growing array of microschools that, at least for the educators who created them or the families who used them, solve any number of the problems plaguing public education: youth mental health is in crisis, teacher morale is flagging, voluntary community associations are desiccated, students are often disengaged if they're showing up at all, bonds of trust between schools and families are fraying.

It takes a special kind of cynic to imagine the current blossoming of small learning environments where teachers are free to realize their peculiar vision for what learning could look like and partner with families to make it happen is the brainchild of a few voucher advocates. Notably, most of the learning environments catalogued by Vela say they don't access public funding at all.

And it's no surprise legions of researchers, journalists, advocates and program officers at education foundations have all latched on to microschools at the same time. They see previous education reform fads (teacher evaluations, personalized learning) sucking wind. They're peering desperately for beams of light amid the post-pandemic gloom. And when they actually visit microschools or talk to educators who work in them, they see what I've seen: The kids are happy. The teachers are energized. Families and community groups, often sidelined in schools, are pulled into the center of the learning experience. If you ask a student what they're doing and why, they’ll tell you, often enthusiastically. These are things we should hope to find in any learning environment. The fact that they stand out underscores the extent of the current malaise.

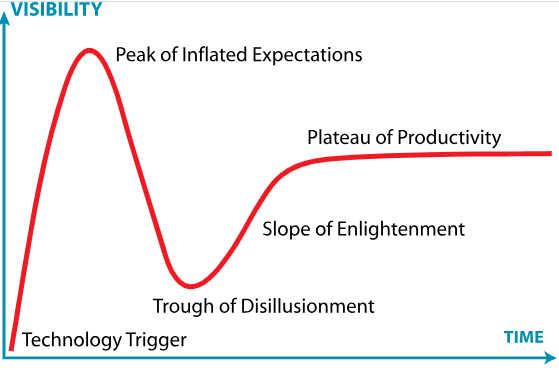

If microschools are following Gartner's hype cycle, they're probably coasting somewhere between the peak of inflated expectations and the trough of disillusionment.

Gartner's Hype Cycle (via Wikimedia Commons)

To reach the plateau of productivity, they're going to have to grapple with questions about financial stability and methods for reporting student outcomes. They'll need to devise new ways to provide special education services, transportation, and other essential infrastructure that ensures they're accessible to all students.

But I'm willing to bet that anyone who actually visited these learning environments, or spoke to the educators who worked there, would come away with their cynicism punctured and a belief that these bottom-up efforts are getting so much attention precisely because they're positing novel solutions to countless different problems facing young people and public education.

Students at CREATE Conservatory soak old newspapers in tea to make them look antique. The school was named one of 64 quarterfinalists for the 2023 Yass Prize.

The Yass Prize kicked off its 2023 education innovation competition today by announcing 64 quarterfinalists from 31 states.

Each school or learning platform that made the list will receive $100,000 to improve or expand its program and move on to be considered as one of 32 semi-finalists.

The group announced today included six Florida schools, plus two national networks with a strong presence in the Sunshine State.

You can see a complete list of this year’s quarterfinalists here.

Past Sunshine State honorees include Colossal Academy, Fort Lauderdale; HOPE Ranch Learning Academy, Hudson; Kind Academy, Coral Springs; RCMA Community Academy, Immokalee; CARE Elementary School, Miami; Colegia, by Academica. SailFuture Academy, a St. Petersburg project-based high school that offers career training and multi-month sailing expeditions was a finalist last year and took home $500,000.

ReimaginED profiled some of the current and previous winning schools here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Stiff competition: The competition drew 2,000 applications from organizations serving 27 million students from every sector in education and every grade in the PreK-12 continuum across all 50 states.

How they won: All Yass Prize applications went through an three-tier review process involving more than 1,000 judges, assessing their alignment with the STOP principles: sustainable, transformational, outstanding and permissionless. (John F. Kirtley, founder and chairman of Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, was among those judging this year’s entries.)

How it began: Philanthropist Janine Yass and her husband, Jeff, created the prize in 2021 to reward the innovation in education that followed from the Covid-19 pandemic, with a focus on underserved populations.

What’s new: This year, the Yass Prize added the Yass Award for Education Freedom Award, which celebrated three states, Arkansas, Iowa and Oklahoma, and allocated money for governors to donate to programs in their states with the potential to scale up quickly. Those three states all created universal education choice programs.

Next Steps: Quarterfinalists move on to the semi-final round, where the list will be cut to 32. Those schools will win $200,000 and progress to the final round on Dec. 13, where finalists will receive additional prize money. One top winner will receive the $1 million grand prize.

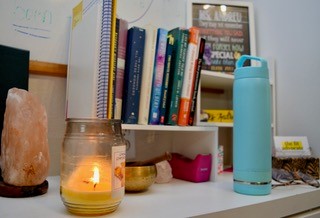

A scented candle lends some ambiance to Lexa Duno's garage classroom. Duno left her job as a teacher in a traditional private school in 2020 to start The Lit Advocate, a tutoring business that focuses on reading, writing and language arts. She and her brother, Carlo Andreu, started edTonomy, an app that helps education entrepreneurs manage their businesses. Photo by Tom Jackson

Lexa Duno became an educational entrepreneur before educational entrepreneurialism was cool, or even a thing. In 2015, as a fifth-grade teacher in a Tampa private school, Duno thought she was where she belonged. It certainly was the place for which her education and training had prepared her.

Even so, she felt a pioneer’s tug, imagining somewhere, somehow, there was a better fit for her skills and temperament. A bilingual literature expert with a degree in creative writing and a passion for poetry, Duno ached for a professional world where she could support students who struggling with literacy or who were challenged by learning disabilities by using evidence-based interventions based solidly in the science of reading.

When coronavirus pandemic came, changing everything, it was not necessarily for the worse. For Duno, it was a time for confronting the hunger that threatened to devour her sense of purpose. In September 2020, she leapt, leaving her job and its regular paycheck to start a home-based literacy tutoring business as — ta da! — The Lit Advocate.

As a teacher, Duno was reborn. Nowadays, her enterprising teaching life is headquartered in a cozy classroom carved from a garage at her blended family’s home on a shady street in Dade City, Florida. Some students she meets in person; others she instructs via internet video. Some of her students benefit from state education choice scholarships managed by Step Up for Students, which hosts this blog.

Duno also worked last year at nearby Cox Elementary School, where she served as a part-time academic intervention tutor in reading and math for students in kindergarten through fifth grade.

As if this sundae needed whipped topping and a cherry, there’s also this: Setting her schedule enabled Duno to publish “They Will Ask: A Story About Embracing Our Differences” in September 2022, an illustrated children’s book about taking pride in an individual’s culture, language, and origins.

And that might have been that, except for this: Duno was made for educational entrepreneurism. As her business blossomed and her referrals boomed, much to the delight of the creative right side of her brain, her left brain was swamped by disorganization. The time-honored tools of teaching, handwritten calendars, ledgers, notes, grade books, were no match for the demands of a freelance educator.

Here’s Carlo Andreu, Duno’s business partner and younger brother: “Lexa started to grow her business, but when she realized … to scale that business … she needed to streamline some of her business administration.”

Which brings us to edTonomy, the app thousands of teachers who, like Lexa Duno, never imagined they needed until they

Florida education entrepreneur Lexa Duno, with her brother, Carlo Andreu. The two founded edTonomy, a classroom organizer app that helps teachers navigate their business operations. Photo by Tom Jackson

launched their own education shops, only to discover, when it came to digitally organizing a free agent’s classroom, there was no app for that.

“We were seeing Facebook comments,” Andreu said, “and comments all over the internet, really, from teachers who were going in the same direction as Lexa, or at least looking for a way to go in that direction.”

And all were saying the same thing: I just want to teach the kids. Where’s the program that will help me organize all the other moving parts — a sort of QuickBooks-meets-Outlook-meets-Microsoft Office-meets-Excel-meets-schoolhouse-Tinder, all swaddled in a Mister Rogers cardigan?

Like Lexa, Carlo favors independent entrepreneurship. So, while he was working for an investment firm in Tampa, he was also looking for an opportunity to launch a tech company. His sister’s frustration, the tip of the teacher tsunami visible just above the horizon, was preparation meeting the moment.

“If what you’re looking for doesn’t exist,” Andreu said, “you’ll have to create it.”

In development for more than a year, edTonomy 1.0 launched in May. Having listened closely, Andreu and the team’s developer, Robin Fowler, digitized everything Duno said she needed, creating a classroom in an app.

Andreu describes it as “a professional tool to manage administrative tasks, support students and their families, and cater to the unique needs of a non-classroom teacher.”

“We’ve put our heart into building a tool that’ll empower educators to see just how valuable their skills, and they themselves, truly are,” Duno said.

Among the edTonomy highlights:

The app is available by subscription, with monthly plans beginning at $39.

With the landscape of school choice changing almost daily, backed by game-changing momentum for education savings accounts, Duno said the time is ripe for education entrepreneurs, those who love to teach, but who increasingly find the traditional classroom stifling. Not that everybody “gets it” just yet.

“We have spoken with investors,” Duno said. “They've said, ‘But educators aren't entrepreneurs.’ ” Here, a meaningful eye roll. “This is something that's extremely frustrating for us. I'm an educator, and I learned to become an entrepreneur, and that's exactly what we're intending to do; we're intending to help teachers who are ready to leave the classroom.”

Instead of finding another outlet for their desire to teach, however, these classroom refugees choose sidetracks that take them out of education altogether.

“We want to help teachers think that there's another option,” Duno said. “You can continue to teach, especially now in a state like Florida” which recently adopted universal ESAs, allowing all K-12 students financial flexibility in their education choices.

With those options for students come opportunities for teachers, Duno said. “They will have the ability to work with a bunch of different kinds of students and to do it without having all that comes with working in the system.”

And for those who don’t want to reinvent the wheel, there’s edTonomy to help them navigate the business side of their brave new career.

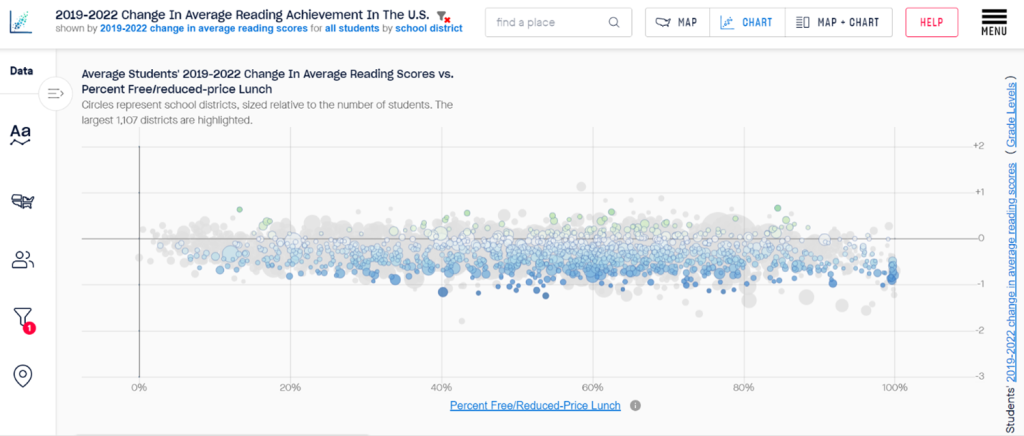

American K-12 education was doing quite poorly before the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. In comparisons to other nations on international exams, American schools spent lavishly but scored poorly. Now matters are worse. The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project recently measured change in reading scores by school district between 2019 and 2022. The below chart plots reading achievement, green is good, blue is bad, and blue dominates green, and the mathematics chart is even worse:

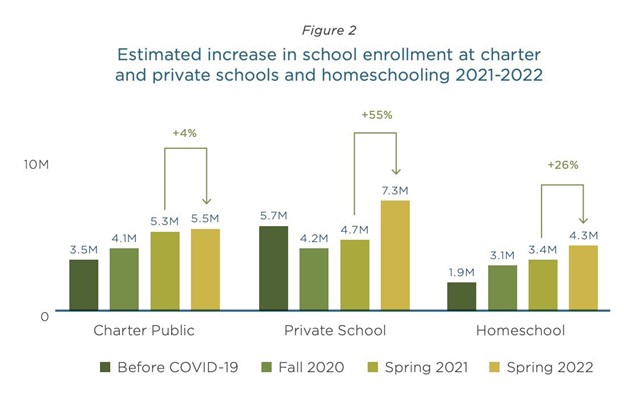

America’s shambolic public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic greatly increased demand for education options outside the districts. Tyton Partners measured which sectors met how much increased demand:

Tyton Partners estimate that between the Spring of 2021 and the Spring of 2022, charter schools increased enrollment by 200,000 students, private schools by 2.5 million students and home schools by 900,000 students. Charter schools have led the way with enrollment growth for decades, raising the question: Is this trend a passing cloud or a long-term shift?

I’m placing my bet on a long-term shift.

Charter schools face a variety of practical and political challenges. Practical difficulties include increased interest rates, building supply chain issues, and construction labor shortages. Political difficulties include increased general political polarization and a Baptist and Bootlegger self-own. Circumstances will vary considerably by state, but if you add it all up, the outlook looks challenging for charter school growth.

Private and home schools by contrast require little in the way of permission by public authorities when compared to charter schools. No statutes create caps for the number of private or home schools; no boards decide which schools may open or which must close. When a pandemic-fueled demand shock came, permissionless education systems answered the call.

The COVID-19 pandemic popularized a Do It Yourself (DIY) education movement. Americans take cues on schooling from friends, families, and social networks. More people doing DIY recently seems likely to lead to still more DIY in the future.

Stay tuned to this space in 2023, and we’ll explore further the long-term shifts taking place in full view of the world. Happy holidays!

Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey at signing ceremony for bill that massively expanded education savings accounts

Editor's note: This post was originally published on realcleareducation.com. The author, Jude Schwalbach, is an education policy analyst at Reason Foundation.

After an Arizona citizens’ referendum failed to block the state’s massive expansion of Empowerment Scholarship Accounts last month, the Grand Canyon State now leads the nation in education customization.

Arizona’s education savings account (ESA) expansion was a critical school-choice success, but the story should not stop here. Policymakers can do two things that go beyond Arizona’s reforms to truly revolutionize a state’s education system: make ESAs the default option for all students and eliminate residential assignment in public schools.

First, policymakers should not limit ESAs to those opting out of public schools but rather make these accounts the default funding system for all students. Instead of funding school districts based on factors such as property wealth, local tax effort, and complex formulas, state and local education funds would be streamlined and deposited into each student’s account.

Under this system, these accounts would not just be used for private school tuition payments. Parents who enroll their children in public schools would pay these schools directly and could also use education savings accounts to pay for tutoring, courses at a community college, classes at a nearby public school, transportation, and more.

To continue reading, go here.

For the past dozen years, the GEO Foundation nonprofit has offered students enrolled at its high schools access to higher education through its college campus immersion program. A state grant for $8.3 million has allowed it to expand the program statewide.

Kevin Teasley loves success stories.

That’s because he has plenty of them to tell.

There’s the student who was on the verge of dropping out of school, only to graduate from high school with a college degree. Then there’s the academically gifted student who started taking college courses at age 13 and earned his bachelor’s degree before he got his high school diploma.

“We have a very different approach to empowering families with choices,” said Teasley, founder of the Indianapolis-based Greater Education Opportunities Foundation, also known as the GEO Foundation, which operates a mix of charter and private schools in Indiana and Louisiana. “Even within our schools we have a very different approach. We don’t believe the money that comes from the state belongs to us. We believe the money belongs to the students.”

Teasley started the nonprofit organization in 1998 to support all quality means of educating children, including public, private, charter and religious schools as well as homeschooling. The foundation also works to develop a community understanding of school choice to align with its belief that providing families with a menu of educational options will strengthen all schools.

Teasley has even more stories these days, thanks to an $8.3 million grant that the Greater Education Opportunities Foundation received from the Indiana Department of Education in 2021. GEO used the grant to extend its college immersion program to six Indiana schools and a public school district.

“When you apply for these grants, you ask for the moon, not expecting to get the moon,” he said. “We got the moon.”

The program allows high school students to take college courses. However, a partnership with the colleges lets the students travel to the local campuses, unlike most dual enrollment programs where students take the classes at their high schools from their own teachers who have been specially trained.

“There’s nothing wrong with that,” he said, “but we don’t think that is as powerful an experience as putting students on a college campus, so they get that whole climate, that culture and experience from a real college professor, from students sitting next to them who aren’t their high school buddies, but other college students, and they could be adults. So, our students get the whole experience while they are at our schools.”

GEO had been offering the program to students enrolled at its own schools for about a dozen years. Teasley says it has helped turn many would-be dropouts into first-generation college graduates.

He said many students at GEO schools, which cater to families who are low-income and minorities, didn’t consider higher education because they have no college role models in their families. At GEO’s school in Gary, Indiana, a community with 50% high school dropout rates, GEO first tried the traditional college prep approach when it opened the school in 2005. They talked up the advantages of college degrees, including higher-paying careers. They arranged for campus tours.

All of that failed.

“It was going right over the heads of kids,” Teasley said. What the students told him was that they valued school mainly for its social scene.

“They said, ‘I’m not really going to high school to go to college. I’m in high school because this is where my friends are. This is where I get to play football. This is where I get to play basketball.’”

Teasley decided he had to change that mindset.

“These kids are smart, but they’re not thinking beyond high school, and what incentive do they have to do well on those state tests or on SAT and ACT tests because they’re not going to college, so why would they do their best on them?”

One 16-year-old student had planned on dropping out. Most of his adult relatives had dropped out, and he didn’t consider himself college material. Teasley challenged him to take the entrance exam at Ivy Tech Community College. If he passed, the school would pay for him to take classes on campus.

When the test results came back, the teen’s eyes lit up as he saw his passing score. Teasley said he was now a college student and would be taking classes at Ivy Tech for free.

“I’ll start paying for you to go to college,” Teasley recalled. “We’re going to do that while you are at my high school.”

The student, who originally had planned to drop out of high school, not only earned his diploma but also an associate degree, an achievement that still makes Teasley swell with pride.

So, when it came time to apply for the competitive acceleration grant, GEO’s application stood apart from the pack.

The department planned to award the grant as part of its initiative to accelerate learning, which for most schools meant remediation for pandemic learning loss. However, Teasley is quick to point out that not everyone fell behind in 2020.

“Many of our students in Gary, Indiana, Baton Rouge and Indianapolis chose to use that time to accelerate, and by that, I mean that that we empowered them to enroll in college courses,” he said. “We had students earn their associate degrees during COVID. They didn’t lose ground; they accelerated.”

Teasley said those students’ experiences inspired his foundation to apply for the grant to help more students across the Hoosier State attend college while in high school.

The GEO Foundation is partnering with six schools and the Vigo County School Corp. in Terre Haute, Indiana. The grant is being used to pay college tuition, tutors and other staff to support the participating students, as well as transportation, which Teasley admits is one of the most challenging areas to administer.

“We’re like air traffic controllers,” he joked.

The programs have paid off, with Teasley estimating that more than 1,000 students have benefited from the grant. Those results align well with GEO’s mission of helping students improve their lives by removing barriers to better education.

For families of modest means, the biggest barrier to college is cost.

“We’re paying full freight for students to get college courses,” Teasley said. “If it’s $1,000 per class, that’s what we pay. We do that because we think it’s a valuable experience for kids. It gives students a reason to stay in high school because they begin to believe they are college capable.”

Education startup KaiPod Learning offers in-person learning environments for online learners and homeschoolers, affording parents the chance to choose the curriculum they think works best for their child. Families can choose 2-, 3- or 5-day plans from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., but students can join their pod as much or as little as they’d like.

Editor’s note: This article from Kerry McDonald, a senior education fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education, appeared Saturday on the foundation’s website.

Curriculum battles in public schools across the U.S. have reached a fever pitch in recent years, with parents and politicians fighting about what children should and should not be taught.

The Cato Institute’s Neal McCluskey keeps a running list of these battles, explaining that “rather than build bridges, public schooling often forces people into wrenching, zero-sum conflict.”

Private education models, along with school choice policies that enable parents to exit an assigned district school if they are dissatisfied, help to avoid these public schooling battles. Parents can choose the learning environment for their children that best fits their individual needs and preferences without fighting a political war on the school board floor.

From curriculum to educational philosophy, private education models offer the variety and personalization of learning options that one-size-fits-all, government-run schooling cannot. School choice policies that enable education dollars to follow students directly, rather than going to school districts, allow lower- and middle-income families access to this diversity of options that higher-income families have long enjoyed.

One education entrepreneur is trying to put parents back in charge of their children’s curriculum, while creating a collaborative, cost-effective space for learning.

Amar Kumar is the founder of KaiPod Learning, a venture capital-backed education startup that brings together the best of online learning with crucial, in-person social experiences and adult mentorship. Kumar, who worked in online product development at Pearson before starting KaiPod, participated in the selective Y Combinator startup accelerator program in Silicon Valley last year while launching his flagship KaiPod learning center just outside of Boston.

To continue reading, click here.

On this episode, reimaginED Senior Writer Lisa Buie talks with Caroline Tevlin, an elementary school Spanish teacher who customizes her students’ education by tapping into their individual learning styles.

On this episode, reimaginED Senior Writer Lisa Buie talks with Caroline Tevlin, an elementary school Spanish teacher who customizes her students’ education by tapping into their individual learning styles.

Tevlin transitioned to teaching online after working in a traditional school setting for six years. Four years into her experience at Florida Virtual School, she enjoys the flexibility as an educator and recognizes its benefits for her students.

“It was such a great fit for me. It was nice to be there at the beginning of the Spanish program. It was so great to have that flexibility along with so many tools I could utilize … This really made me think creatively and connect with students and meet them where they’re at. I have always known that every student learns differently.”

EPISODE DETAILS:

Amy Marotz worked with Microschoolbuilders.com to create her "one-room schoolhouse" in Stillwater, Minnesota.

Amy Marotz’s decision to start a microschool began the way such decisions have begun for others: She became a parent.

The former educator, who taught English at a charter school for low-income students in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, toured her zoned district elementary school when it was time to enroll her older child. Unlike her younger child’s preschool, a 40-minute drive from her home, the school was within easy walking distance.

That turned out to be the only advantage Marotz and her husband found.

“We both came back feeling a disconnect from the entire ideology of it,” said Marotz, who shared her story at the recent Liberation of Education conference. “We had embraced a screen-free lifestyle as young parents, and first graders were having 20 minutes on the computer for math.”

Marotz asked how much time students spent each day outdoors. The answer: about 10 minutes.

“Why should I let her spend 10 minutes outside when I know I can provide something that’s way more tailored to her individua needs?” thought Marotz, a certified teacher with a master’s degree in education.

That’s when she made up to her mind to become a homeschool mom. She started slowly, with three students: her daughter, her pre-school age son, and a neighbor’s child.

Like Marotz, her children were born sensitive to sensory stimuli, so she tailored her instruction to fit those needs. She held classes in the lower level of her home. Soon, three students grew to five, and five became seven.

Marotz knew she was no longer just an educator; she was running a business. For that, she needed help.

In addition to learning core subjects such as reading, language arts, math, science and social studies, students at Marotz's school care for animals.

She connected with Mara Linaberger, founder of Microschoolbuilders.com. Linaberger, a former educator and school administrator who holds a doctorate in instructional technology, founded the company several years ago to help teachers and parents with the business of education.

Linaberger asked Marotz what she wanted most in a school and helped her develop a budget and a sustainable business model. The result was Awakening Spirits, a private micro-school that serves children who have sensory issues.

The school moved from Marotz’s home to a home on a 15-acre property in Stillwater, Minnesota, that looks like a one-room schoolhouse on the inside. Third through eighth graders learn together in the main classroom that boasts a picture window offering a view of the outdoors, where students spend about two hours per day.

(The school also has a preschool for students ages 3 to 6.)

“We wanted them to have access to animals and nature,” Marotz said.

Décor is simple so as not to overwhelm the students’ senses. In addition to learning core subjects such as reading, language arts, math, science and social studies, students care for animals. They also get to spend their afternoons pursuing “passion projects” that interest them.

One day a week, students venture out on local field trips, with occasional long-distance road trips throughout the year that they help plan as part of their learning.

Marotz, who is now a member of Linaberger’s team, has advice for anyone seeking to open a microschool. First on the list: Identify your market. In Marotz’s case, that was students who because of their sensory issues, didn’t fit in at a traditional school.

Other tips: