Choice opponents have been known to throw contradictory arguments out against private choice programs. One moment they will claim that the majority of kids using universal choice programs were already going to private schools. A few moments later they will claim such programs are draining district schools of students and money. The irony of these mutually exclusive claims will often escape the person making them, and you can see hints of both in this New York Times podcast titled Why So Many Parents are Opting Out of Public Schools.

Sigh

Choice opponents make all kinds of claims, but not many can withstand even a modicum of scrutiny. Let’s take for instance a widely repeated fable- that Arizona’s universal ESA program has “busted” the state budget.

If you actually examine state reports like this one for district and charter funding and also this one for ESA funding, you wind up with:

Arizona districts have exclusive access to local funding among other things and are by far the most generously funded K-12 system in the state. Districts, charters and ESAs all use the state’s weighted student funding formula, and ESAs get the lowest average funding despite having a higher percentage of students with disabilities participating than either the district or charter sector.

If you track the percentage of students served by the district, charter and ESA sectors respectively, and the funding used by each as a percentage of the total, you get:

So, there you have it; supposedly the sector educating 6% of Arizona students for 4% of the total K-12 funding is “bankrupting” the state of Arizona. Meanwhile the system, which generated an average of $321,700 for a classroom of 20 ($16,085*20), is “underfunded.”

A group of 20 ESA students receiving the average scholarship amount receive $123,780 less funding, but they are (somehow) “busting the budget.” The fact that a growing number of Arizona students opt for a below $10k ESA rather than an above $16k district education tells us something about how poorly districts utilize their resources. So does the NAEP.

There is a school sector weighing heavily upon Arizona taxpayers, but it is not the ESA program.

A recent interview by Tyler Cowen of John Arnold has been making the rounds in ed reform circles, see Michael Goldstein’s write up here. Here is a taste of the interview:

Tyler Cowen: There’s a common impression—both for start-ups and for philanthropy—that doing much with K–12 education or preschool just hasn’t mattered that much or hasn’t succeeded that much. Do you agree or disagree?

John Arnold: I agree. I think the ed reform movement has been, as a whole, a significant disappointment. I think there have been isolated pockets of excellence. It’s been very difficult to learn how to scale that. I think that’s largely true of many social programs or many programs that are delivered by people to people, that you can find a single site that works extraordinarily well because they have a fantastic leader, and that leader might be able to open up a few more sites. But then, when you start to scale it to 50 sites, and start to go across the nation, it all mean-reverts back to what the whole system is providing.

“We’re a dispirited rebel alliance of do-gooders,” Goldstein writes gloomily, but the underlying premises deserve scrutiny, as it strikes me as entirely too pessimistic. Let us for instance look at the academic growth rates for charter schools in Arnold’s home state of Texas as recorded by the Stanford Educational Opportunity Project. Each dot is a Texas charter school, and green dots on or above the zero line display an average rate of academic growth at or above having learned one grade level per year:

This chart deserves a bit of your time to marvel at. While receiving far less total taxpayer funding per student, the Texas charter sector has not only created a large number of schools with high academic growth, but they also place competitive pressure on nearby district schools to improve their academic outcomes. Texas charter schools have not cured the world’s pain, nor have they dried every tear from our eyes. It is hard for me, however, to view it as anything other than a tremendous academic success, and Texas is not alone. Here is the same chart for charter schools in Arizona:

Again, we see far more high academic growth green-dot schools than low academic growth blue-dot schools. Once again, this sector is a bargain for taxpayers, and the sector placed competitive pressure on districts to improve. By the way, Arizona has a larger number of charter schools in low-poverty areas than Texas. That helped crack open high-demand district schools to open enrollment, which is why a real Fresh Prince can go to school in Scottsdale but not in Bel Air or Highland Park in Texas, which opened a vast new supply of choice seats in school districts. The do-gooder rebel alliance, it turns out, made a serious political and educational error when they effectively in a variety of ways excluded suburban areas.

You live and (hopefully) learn. Speaking of Bel Air, behold the magnificence of the academic growth of California’s charter school sector:

Oh, and then there is the 2024 NAEP to consider:

If you do not live in a state whose name starts and ends with the letter “o” you are likely to be happy with your charter sector’s performance vis-à-vis districts, which admittedly, is a low bar. Of course, all this data is messy and neither the growth measures developed by Stanford nor the NAEP proficiency data above capture long-term outcomes- such as do schools produce good and productive people who are well-prepared to exercise citizenship. We are looking through a glass darkly.

The do-gooder education reform alliance should indeed take stock of which efforts produced meaningful results, and which proved to be costly quagmires, and recalibrate their efforts accordingly. To paraphrase the Bard: the education reform movement has 99 problems, but the inability to scale success in choice programs ain’t one.

The NAEP released 2024 results last week, and the results continued to disappoint, especially for disadvantaged student groups. While scores began to recover among high end performers, the decline continued among lower performers, as can be seen in the eighth grade math chart below:

Rick Hess summarized the bad news:

Fourth- and 8th-grade reading scores declined again. Between 2019 and 2024, 4th-grade reading is down (significantly or otherwise) in every state but Louisiana and Alabama. Among 8th graders, fewer than one-in-three students were “proficient” readers. Thirty-three percent were “below basic.”

On fourth grade reading, note the gradual improvement across racial subgroups from 2003 to 2015, but then the backsliding since then across groups. Critically, the slide started before the COVID-19 pandemic (the 2017 and 2019 exams both occurred before the outbreak). The decline between 2022 and 2024 is especially disappointing.

On fourth grade reading, note the gradual improvement across racial subgroups from 2003 to 2015, but then the backsliding since then across groups. Critically, the slide started before the COVID-19 pandemic (the 2017 and 2019 exams both occurred before the outbreak). The decline between 2022 and 2024 is especially disappointing.

This continued slide occurred despite the federal government putting $190 billion into the school system. The 2024 NAEP was the second post-pandemic data collection (after 2022). With a sad predictability, the return on investment for this staggering funding appears to be minimal.

The defacto “plan” in the public school system appears to be to age the students out of the system unremediated. The 2026 fourth grade NAEP, for example, will be testing students largely too young to have been enrolled during the 2019-2020 school years. The eighth grade NAEP will take longer to age the pandemic fiasco-affected students out, but this will eventually happen as well. The affected students, however, will be aging not out of the elementary and middle schools but into society.

The news was not all grim: nationwide Catholic school students show signs of academic recovery. Unfortunately, the Catholic results are the only private school scores available, but they show a notably different trend than those in the public school system. See for example the trend among Hispanic students in Catholic schools and public school students on eighth grade mathematics:

The gap between Hispanic students attending Catholic schools has effectively moved from approximately a grade level, to approximately two grade levels in 2024. Louisiana was also a bright spot in the 2024 results. More number crunching to follow, but what I am finding thus far is the closer you look, the worse the results seem.

Australian defense economist/YouTube PowerPoint superstar Perun has provided another insightful video which is must-see viewing for anyone seeking to understand politics.

US Navy Procurement Disasters - The Littoral Combat Ship and Zumwalt Class Destroyer is a cautionary tale for anyone seeking to expand the role of politics in life and should be mandatory viewing, full “Clockwork Orange” style if necessary, for anyone seeking any office.

Given that the runtime lasts over an hour, I’ll do my best to summarize. At some point, Navy wargamers discovered that a scenario closely resembling “Iran attempts to close the Persian Gulf in part by using shore-based missiles and drones” proved very difficult for players controlling the U.S. Navy. Think of all the problems the already obsolete HIMARS systems gave the Russian army in Ukraine, but apply those “shoot and scoot” tactics to ships.

The Navy brass decided they needed a new type of warship to counter such a threat: the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS). It needed to be fast, stealthy, and multifunctional. That last part drew inspiration from modular ships in the Danish navy. In this context, the idea developed into modules that could be put on/off the ship to expand the capacity to fight shore-based opponents, sweep sea mines, or combat submarines.

Okay, so the disaster begins to unfold when the Navy does not settle on a single design but instead on two designs. From an operational standpoint, this made absolutely no sense, complicating a whole suite of requirements to train crews and repair ships. However, it made all the sense in the world in one important way: politics. By adopting two different ship designs, you made many members of Congress happy.

This disaster is just getting started, however. Both ship designs have serious problems. One of them had a super advanced propulsion system, but it is delicate and requires specialized contractors to repair it. The other ship's design had a problem keeping water out.

Next up, while modules might be a great idea for the Danish navy, the Danish navy rarely sails very far from Denmark. This is not the case for the U.S. Navy, which sails around the globe. If the modules are to be very useful, you need to be able to change them out, which means they must be proximate to wherever you are going to use them. When the Navy wargamer nerds played subsequent games of Navy Dungeons and Dragons, the nerds playing the opponents put the destruction of modules sitting onshore somewhere near the top of their to-do list. Hopefully, you like the module you are using now; you won’t be making any changes anytime soon.

These ships were such a disaster that the Navy tried to retire one of them only five years after it was commissioned. I say “tried” because you’ll be shocked to hear that politics intervened again, as Congress did not want the ships retired.

A scenario very similar to the original wargame broke out in the Red Sea last year courtesy of the Houthis. The U.S. Navy did not send forth the mighty LCS to combat the Houthis’ shore-based missile and drone attacks on commercial shipping, preferring to use, you know, functional warships. Unable to retire these duds, the Navy has decided to pop the minesweeper module on them and use them to replace aging minesweepers. Without a doubt, these are the most catastrophically expensive minesweepers produced in human history.

My telepathic powers inform me that some of you dear readers are wondering what any of this has to do with K-12 education. Thanks for asking! Running a public school system, just like procuring new ships for the Navy, is a political process. Politics can (sometimes, hopefully) involve reason and logic, but far more often it runs on the self-interests of lobby groups and politicians. Deciding to order two deeply flawed ships instead of zero made no sense if you wanted to fight and win a war, but it made perfect sense in serving the interests of the players in this political game. Lucky you; you get to pay the bill.

Politics gifted us with costly minesweepers with overpowered and delicate propulsion systems or issues with floating. Likewise, politics has straddled the United States with one of the most costly and ineffective school systems in the world. When it comes to the education of your children and grandchildren, politics is not a game you want to play.

On Jan.17, 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower delivered a 10-minute farewell address after having served his nation as president. He had interesting things to say, such as:

As we peer into society's future, we – you and I, and our government – must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for our own ease and convenience the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

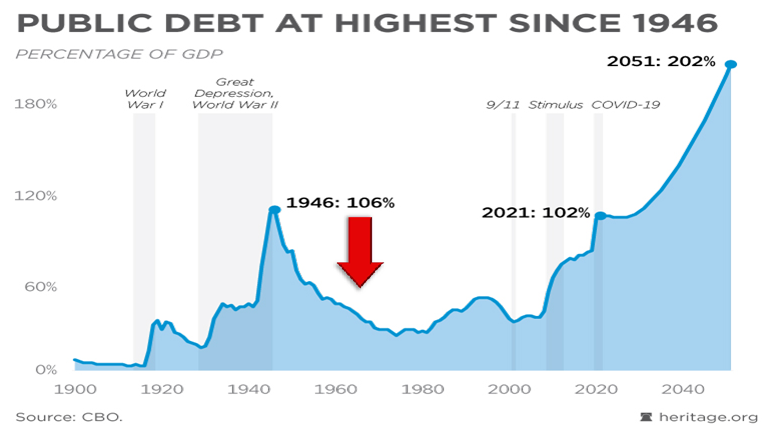

How is the whole not plundering the precious resources of tomorrow thing going for us? Not well lately (red arrow designates the end of the Eisenhower administration).

In this same address, Eisenhower famously warned us about the “Military Industrial Complex.” Having served as supreme commander of Allied Forces in Europe during World War II in addition

to the nation’s 34th president, Eisenhower’s warning received and continues to receive grave consideration:

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. . .Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. . . In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

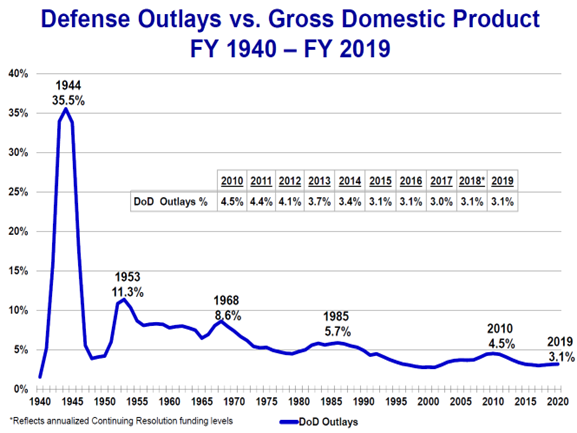

Luckily, military spending did not spiral out of control. American military spending as a percentage of GDP declined over time. The United States won the Cold War, managed to successfully close a huge number of unnecessary military bases (not the sort of thing an overly powerful Military Industrial Complex would like to see). The United States may have had a “Military Industrial Complex” problem to manage, but it managed it successfully.

We’ve yet to successfully manage our school District Lobbying Complex.

Part of the challenge of the Military Industrial Complex was that defense contractors (quite deliberately) spread facilities widely across congressional districts. Military bases likewise were ubiquitous. The Phoenix area for instance once hosted two Air Force bases, with another less than a couple of hours drive away in Tucson. Austin and San Antonio, Texas, each had Air Force bases. Obviously once the world went all Red Dawn and we lost the bases in Tucson and San Antonio, our forces would regroup in Phoenix and Austin or…something (?)

Such things may not have made a lot of sense from a national security standpoint, but they were great from the standpoint of politics. School districts likewise have amassed an abundance of underused facilities. Keeping them around makes little utilitarian sense, but the District Lobbying Complex is not eager to give them up for political reasons.

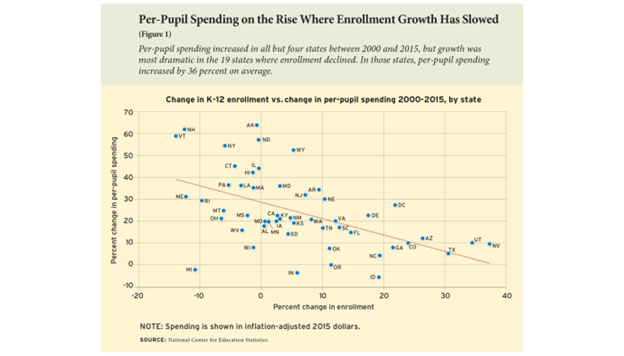

In recent decades the states with declining or slow K-12 enrollment growth have had the largest increases in per pupil spending. That has been quite a feat for what we can only half-jokingly call the District Lobbying Complex, but it seems unlikely to be sustained. Like the Military Industrial Complex, the district system is spread far and wide across the country, and the education unions have been ranked as among the most powerful state level special interest group.

The federal government provides about 35% of the average state’s budget and has tested the outer limits of fiscal insanity with a determined vigor (see first chart above). How long they will be able to keep this up remains unknown but put me down for “less than forever.”

Like the Military Industrial Complex, the District Lobbying Complex may prove to have already peaked. The period in which states could turn up the per pupil spending knob despite declining enrollments coincided with and was enabled by America’s massive Baby Boom generation being in their prime earning years. The average Baby Boomer turned 65 in 2022. Any guesses on where their spending priorities will lie in a competition between their health care and retirement programs and K-12? American families, in increasing numbers, are hitting the exits for districts in search of better opportunities. And then there is the baby bust that began decades ago to consider.

The rise of district employee unions certainly squared with Eisenhower’s “disastrous rise of misplaced power.” This power, however, has gone into an inexorable decline.

When educational options expand, there's usually a big set of beneficiaries that don't get much attention: Students who remain in district schools.

It's one of the most consistent findings in studies of vouchers and other education choice scholarship programs. Studies have found expanding charter schools have produced similar findings. When students gain access to new alternatives, nearby public schools improve their performance. A recently published study of Florida's growing choice programs has found this benefit grows larger as the programs mature and more students use scholarships.

This benefit rarely gets the attention it deserves. If it did, it might cause policymakers to rethink funding practices designed to shield district schools from competition.

A new policy brief from EdChoice breaks down the different approaches states use to shield districts from the impact of declining enrollment. Some of these policies are directly tied to the growth of new choice options, like Massachusetts' law that reimburses school districts for students who leave to attend charter schools.

EdChoice authors James Shuls and Marty Lueken note that while it might make sense to insulate districts from sudden swings in funding or enrollment, policymakers should use them cautiously, because "they undermine efforts to increase educational opportunity by separating funding decisions from students."

Put differently, limiting the fiscal pain of losing students can also weaken the signal that spurs district schools to improve. This is likely one reason why one of the few studies that did not find a private school choice program produced a performance benefit for public schools was in D.C., where public schools are "held harmless" when students leave to attend private schools using the Opportunity Scholarship Program.

A new study from Korea offers more insight. In that country, public and private schools both receive public funding, but private schools have more flexibility over decisions like hiring and firing teachers, similar to charter schools in the U.S.

However, recent policy changes introduced fully autonomous private high schools that enjoyed even more flexibility and did not receive government funding. When these new options came online, the government guaranteed funding for public and private schools, even if they lost students.

The result? There was no improvement in math test scores for public or private school students. Language test scores did improve for private-school students, but not for public-school students, and the authors suggest one likely reason: Private schools had more autonomy, and therefore more flexibility to respond to competition. Even if they weren't at risk of losing money, they were at risk of hurting their reputations if large numbers of students opted to leave.

In other words, while it makes sense to cushion school districts against unexpected financial swings (as Florida does), districts should also have strong incentives to keep students happy (so they continue enrolling in their schools). And they should have the flexibility to mount a competitive response.

By News Service of Florida

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Florida lawmakers are gearing up to provide additional funding to a part of the state's school-voucher program that serves students with special needs, as some proponents of the scholarships say demand has outpaced supply.

The state Legislature is gathering for a special session starting Nov. 6 to address a range of issues. A joint proclamation from Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, R-Naples, and House Speaker Paul Renner, R-Palm Coast, said the session will include an effort to provide “a mechanism to increase the number of students served under the Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with disabilities.”

Passidomo sent a memo to senators on Oct. 20 saying the special session will deal in part with “additional funding for students with unique abilities.” Lawmakers will “address demand” for the program, Passidomo’s brief description of the plan said.

The session will kick off roughly seven months after the Legislature and Gov. Ron DeSantis approved a massive expansion of the state’s voucher programs. And while school-choice advocates have heralded the development as ushering in “universal school choice” in Florida, some are calling for an elimination of a cap on participation in the scholarship for students with special needs.

Steve Hicks, president of the Florida Coalition of Scholarship Schools, is among those who maintain the program should be expanded.

“It’s a cap that limits the number of kids in the program. It’s not that the providers don’t have any space. It’s a very different conversation. The providers are saying we’ve got space. But the state has said, we put a limit on how much money we’re willing to spend,” said Hicks, who also is chief operating officer of Center Academy Schools.

Steve Hicks

In a recent interview with The News Service of Florida, Hicks recounted working in the school-choice space in Florida for 25 years. The current scholarship program for students with special needs — called the “Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities” — is the product of lawmakers combining what formerly were the McKay and Gardiner scholarship programs.

“When the McKay scholarship was operational, for over 20 years, there was no limitation on the number of students who could get in the program. This is a salient point here, this is at the heart of this whole issue,” Hicks said.

The 2021 law that established the Unique Abilities scholarship also set a cap on participation in the program, which is 40,000 students this school year. The law allows the cap to grow each year by 3 percent "of the state’s total exceptional student education full-time equivalent student enrollment," according to a fact sheet on the state Department of Education’s website.

To be eligible for the Unique Abilities scholarship, the law requires that students be eligible to enroll in a Florida public school and have what’s known as an Individualized Education Plan, or IEP, or have a diagnosis of a disability from a licensed physician or psychologist.

Students who receive those vouchers face a participation cap that the broader population of students do not, Hicks told the News Service.

“It doesn't make sense to me that the kids with the greatest need, who could be helped the most, are standing on the sideline waiting for an opportunity while all the other students have been given the opportunity with no limitations,” Hicks said.

“The two major issues are the cap, and the funding dates. That’s very important,” Preston, owner and director of Diverse Abilities Center for Learning and Therapy, said in a recent interview.

Preston said payments that were due Sept. 1 weren’t received until Sept. 26 by her South Florida school and other operators. Preston said that as of Saturday, the school still had not received the full amount for the vouchers, only getting what she described as partial payment.

Several families are waiting to get approval for a voucher that could be used at Preston’s school, she said. While her school has available spots, the lack of scholarships is preventing the potential students from enrolling, Preston added.

“I have six people waiting right now, for FES-UA (the Unique Abilities scholarship). They want to get into my school and they can’t afford it. And their kids are not getting full services in public school. And the parents are really upset because they have to wait,” Preston said.

Preston argued that the cap on participation should be eliminated.

“Completely gone. It should have never been there in the first place. It’s discrimination against kids with unique abilities,” she said.

It’s not uncommon for states that have vastly expanded voucher programs to see an influx of demand — which one expert told the News Service is “notoriously difficult to estimate.”

Shaka Mitchell, an expert on school-choice programs who works with the American Federation for Children, said interest in the vouchers is unlikely to wane. The option to “customize” education for a student with special needs often is attractive to families, he said.

“For those students especially, the local-zone school is less able to adapt to a student’s unique needs than it is a typical learner. You’re seeing high demand with typical learners, so you would expect to see even more where there are unique needs,” Mitchell said.

Florida, which Mitchell said has been at the “forefront of school choice for years,” would not be alone in making efforts to further expand its voucher programs to make space for demand. Legislators throughout the country in states with school-choice programs have had to come back to the table to draw up plans to expand them, according to Mitchell.

“The way that I would characterize it, these laws pass and then lawmakers realize that there’s so much demand that frankly the lawmakers have to be responsive to the parents who are still raising their hands and saying ‘Hey, we want to participate too,’” Mitchell said.

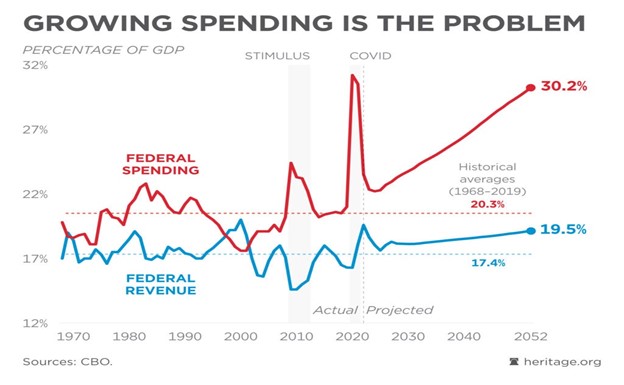

Back in 2015, I authored a study sounding the alarm regarding America’s changing age demography and how it would soon challenge K-12 education called Turn and Face the Strain. The basic case was that states face a gigantic increase in their elderly populations and a substantial projected increase in their K-12 populations, and the patron of state governments, the federal government, had huge unfunded liabilities. Eight years later, things are different than anticipated, and entirely worse.

If you want to start with the “good news,” which is actually bad, the country had a Baby Bust not reflected in the Census Bureau population estimates available in 2015. In the short term, smaller youth populations will relieve state financial burdens, but in the medium to long term, today’s youth population represents tomorrow’s working-age taxpayers. Limited youth translates into a limited future.

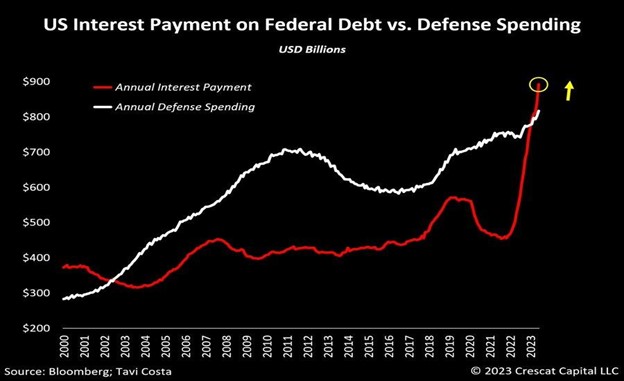

Now for the bad news: our federal government has exceeded previous records for fiscal irresponsibility. The federal government has been spending more than it takes in for decades, borrowing to make up the shortfall. During most of these recent decades, members of America’s massive Baby Boom generation were in their prime earning years, paying lots of taxes and saving for their retirement. Not coincidental to the rather alarming trend seen in the chart above, the average Baby Boomer reached the age of 65 in 2022. Right on cue:

To be sure, there is more to the above trend than Baby Boomer retirement, including increased long-term interest rates and federal spending that would make inebriated sailors blush.

Meanwhile the march of Baby Boomer retirement continues unabated, with all surviving Boomers reaching the age of 65 by 2030. The federal government must roll over debt on an ongoing basis, and those super-low long-term interest rates are gone.

State and local governments primarily fund K-12, but this does not mean these larger trends will not affect them. State governments, for example, received 38% of their revenue from the federal government in fiscal year 2022, and the states are also in the health care financing business through the Medicaid program. Elderly people are heavy consumers of such health care, and every state is getting more and more elderly residents.

States face a short-run “fiscal cliff” with the expiration of COVID-19 relief money, but this is a minor concern in the grand scheme of things. Public schools never seemed to find much in the way of productive use for the funding in any case. The larger dynamic, however, is concerning. If the public school system presided over historic declines in achievement when possessed with more money than they ever expected, what will happen to academic achievement as the funding trend reverses? Is K-12 education doomed? I think not.

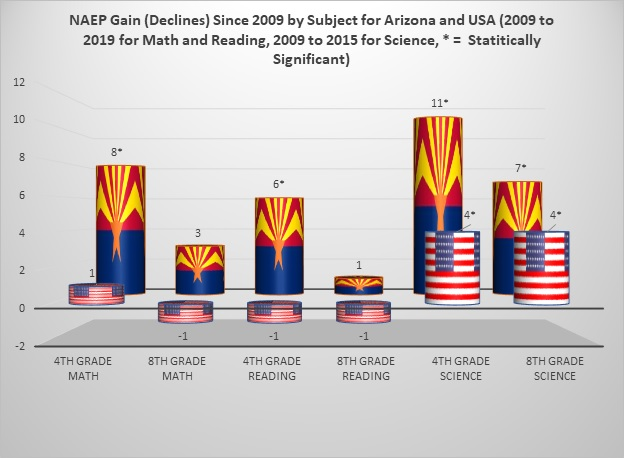

Arizona’s economy was drop-kicked with a steel-tipped boot during the Great Recession and saw some of the largest K-12 funding cuts in the country. Arizona students, however, were the only state student body to make statistically significant academic gains on all six NAEP exams given between 2009 and 2015.

During this period, Arizona lawmakers expanded scholarship tax credits and created the first education savings account (ESA) program. Charter school operators able to access capital during financial chaos found a once-in-a-lifetime (hopefully) opportunity to acquire campus space. This, in turn, created powerful incentives for districts to participate in open enrollment. Many high-demand schools replicated and expanded; low-demand schools saw their enrollments decline. It appears that Arizona families chose wisely overall.

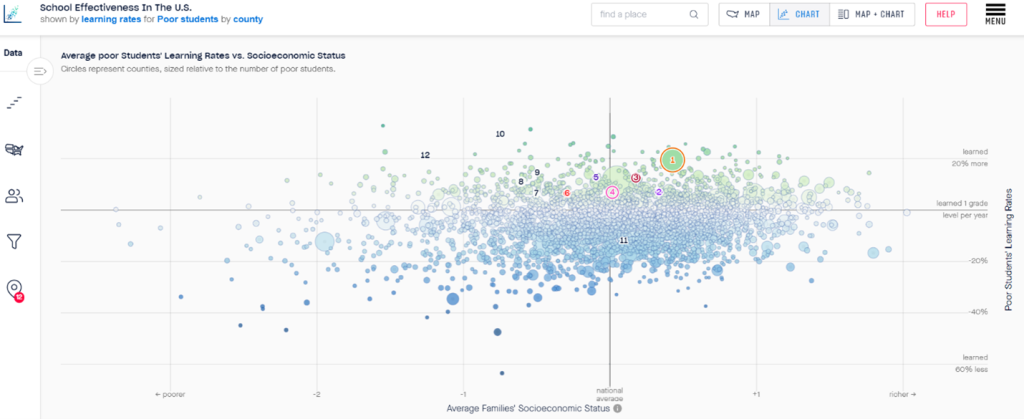

The chart below is from different sources of data (linked state test data) from a different source (Stanford Educational Opportunity Project). It shows academic growth for low-income students from 2008 to 2018 by county. It shows the only Arizona county lacking above-average student academic growth (small and rural Greenlee-number 11 on the chart) had **cough** no charter or private schools.

Can Arizona pull this off again? Only time will tell. High interest rates have slowed charter school construction, but microschools and ESAs have stepped into the breach. Is your state ready for the strain? Your time to prepare is running out quickly.

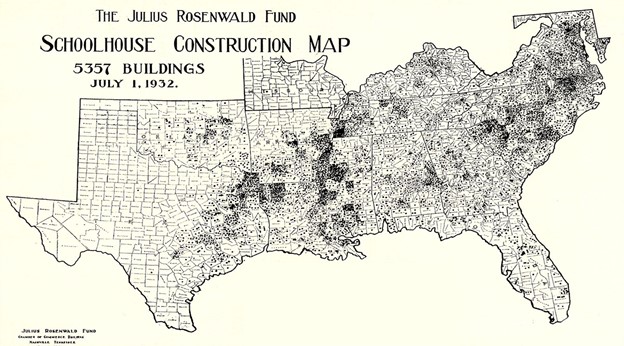

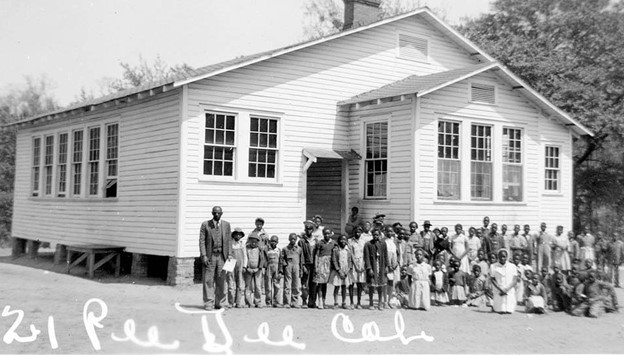

Rosenwald schools served as a forerunner of the modern choice movement. As the Smithsonian Magazine explained:

Between 1917 and 1932, nearly 5,000 rural schoolhouses, modest one-, two-, and three-teacher buildings known as Rosenwald Schools, came to exclusively serve more than 700,000 Black children over four decades. It was through the shared ideals and a partnership between Booker T. Washington, an educator, intellectual and prominent African American thought leader, and Julius Rosenwald, a German-Jewish immigrant who accumulated his wealth as head of the behemoth retailer, Sears, Roebuck & Company, that Rosenwald Schools would come to comprise more than one in five Black schools operating throughout the South by 1928.

The Rosenwald schools played a vital role in advancing Black education in the American South and resembled the later charter school movement in important ways, with philanthropy providing the building infrastructure and other startup needs, with the states paying for the ongoing operating funding. Like charter schools today, the states in question did not fund Rosenwald schools on an equitable per pupil basis. Nevertheless, they made a lasting contribution.

The Rosenwald school movement began a long decline with the passing of Julius Rosenwald in 1932. Rosenwald had hoped that states would continue to build these schools, but this hope was dashed. Concentrated in rural areas and operating in the Jim Crow South, these schools were incredibly disadvantaged in advocating their cases in state legislatures. While a few of the Rosenwald buildings continue to exist, they stopped functioning as schools many decades ago.

A more enduring legacy awaits latter day education philanthropists such as John Walton and Ted Forstmann. Together Walton and Forstmann founded the Children’s Scholarship Fund, which has granted almost a billion dollars in scholarships. Unlike Rosenwald, Walton and Forstmann have seen a now majority of states take up the role of financing alternative schools through mechanisms such as vouchers, tax credits and education savings account programs. A whole new generation of small community schools has emerged in the process, such as those featured here on Reimagined:

Unlike the Rosenwald schools, or sadly even charter schools in most states, the next generation of community schooling has already included all types of communities, leading to a broader base of support. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Dealers figured out that the best way to secure social insurance programs was to include everyone somewhere back around the time of Rosenwald’s death. Accordingly, Social Security is alive and well while Rosenwald schools lived their time but then faded due to a lack of political support.

Many decades passed before the choice movement embraced the New Deal insight, but much better late than never. Now America families and educators have a movement built to last.

Victory College Prep, a charter school that opened in Indianapolis in 2005, received a seven-year charter renewal from the Mayor’s Office of Education Innovation in 2018. The Urban League of Indianapolis has recognized Victory College Prep as a School of Excellence.

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on in.chalkbeat.org.

Republican lawmakers are advancing major changes to the state’s school funding system to benefit charter schools and districts with relatively low property tax values.

The proposed Republican House budget, along with a newly amended GOP Senate bill, would rework Indiana’s property tax system to pump more funding into charters and level what lawmakers say is an unfair playing field for charters and traditional public schools. Lawmakers also might create a dedicated funding stream for charters’ capital expenses that would replace the so-called “$1 law.”

But the proposals have been sharply criticized by Democrats and traditional public school leaders, who argued that the changes would come at the expense of thousands of students in traditional public schools.

The bills channel issues at the heart of a recent dispute over tax revenue in Indianapolis Public Schools. The district withdrew its plan to ask voters for new property taxes on the May ballot, amid criticism from charter school supporters that the draft ballot measure did not provide charters enough money. If the proposals become law, they could change the long-term balance of fiscal power within the state’s public education system.

Together, House Bill 1001 and Senate Bill 391 would do the following to boost funding for charters and school districts with low property values:

To continue reading, click here.