MELBOURNE, Fla. – When it comes to her son’s education, Denice Santos always thinks about the big picture.

“What can we do to merge his goals?” she said. “Education, and then, of course, becoming a pilot.”

Her son, William, 12, has wanted to fly airplanes for half his life. He took control of a plane for the first time when he was 8. He’s nearly halfway to the required 51 hours of flight time needed to earn a pilot’s license.

A Florida education choice scholarship is helping him reach that goal.

William receives a Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship available through the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program managed by Step Up For Students. PEP provides parents with flexibility in how they spend their scholarship funds, allowing them to tailor their children’s learning to meet their needs and interests.

William Santos stands in front of a two-engine airplane that he has flown during his training flights.

For his needs, William attends Florida Virtual School, where he is a straight-A student.

For his interests, William heads to Melbourne Flight Training twice a month for flight lessons. Both are paid for with his PEP scholarship, with the flight lessons covered under enrichment courses.

“I’m not just thinking about right now, his education experience right now. I’m thinking long term,” Denice said. “What’s after school? What’s school building to?”

William said he is thinking about attending the United States Air Force Academy. Or maybe a career in law enforcement where he could put his flying skills to use. Border patrol? Possibly.

He’s recently developed an interest in flying helicopters, which could open another career avenue. The family lives in Melbourne Beach, located in Brevard County, and the Brevard County Sheriff's Office has an aviation unit with four helicopters.

He could also become a commercial pilot and fly for an airline or fly charters for a private company.

“The sky is the limit,” said Denice, who chuckled at her choice of words.

***

William was 6 when he attended the Cocoa Beach Air Show with his mother and father, Kevin. There were flying machines everywhere – F-22s and F-35s, F-16s and B-52s. They screamed overhead and rested majestically on the ground.

He was hooked.

When they were leaving, William said, “Mom, when I grow up, I’m going to be a pilot.”

“He’s always been super decisive,” Denice said. “I knew he wasn’t kidding.”

Denice checked for the minimum age requirement needed to begin flying lessons. Turns out, there is none. You do have to be between 8 and 17 to participate in the nationwide Young Eagles program, which offers free introductory rides for youngsters interested in flying. William was in the air as soon as he turned 8.

“They take kids up for 30 minutes with the pilot, and they get a little taste of it to see if they like it. Is this something? Are they afraid, or does it spark something? William did 10 of those, and we said, ‘OK, this is a thing.’”

Soon, Denice and Kevin were searching for a flight school. They settled on Melbourne Flight Training, which is 20 minutes from home.

William poses in front of the wall containing pictures of all the pilots who earned their license after training at Melbourne Flight Training.

“When I was a kid, I always liked planes,” William said. “Even when I would go on flights as a baby, I would never cry. I would love it, every minute. It was the best thing ever. And I was never really afraid of heights. It didn't bother me much.”

That’s good, because his first flight with Young Eagles was in a BushCat Light Sport Aircraft, a small plane that has non-traditional doors – they are clear plastic and can be removed. You can fly with or without them.

“It was kind of ever so slightly scary,” William said. “Since I was young, I was like, ‘Uh, am I sure about this?’ And many, many flights later, I'm here.”

He has flown 25 times with an instructor and has nearly 20 hours of flight time. He will need to turn 17 and have a minimum of 51 hours before he’s licensed. He will also need to be medically certified to fly and pass a written exam that covers weather, navigation, flight regulations, and aerodynamics.

Dr. Tracey Thompson, the student advisor at Melbourne Flight Training, said it’s not uncommon for someone as young as William to take lessons.

“But,” she added, “he’s been up 25 times, and for someone his age to be up that many times, that’s phenomenal. His consistency, his passion, he wants to do this all the time.”

Jonathan Gaume is William’s instructor. He said he’s never worked with a student this young and is impressed by William’s interest and enthusiasm.

While he’s on pace to reach his 51 hours when he’s 17, William would like to accelerate his training and reach those hours when he’s 16.

Why?

“Because I find this fun,” he said.

As for being one of the youngest pilots training at Melbourne Flight Training, “You know, it's been really the only thing I’ve done since I was 8. It’s been the thing I've always looked forward to.”

***

William has trained several times in a four-seat plane, and Denice has accompanied him during those flights. She said she’s noticed a level of peace when William is flying.

Gaume noticed it, too. He said William’s confidence spikes as they climb into the aircraft.

“He has key elements to being a good pilot: calm, confident and in control,” Gaume said.

The flight path takes William over the Atlantic Ocean, where they sometimes fly around thunderstorms. A recent lesson took place in a twin-engine plane. Gaume killed one of the engines, and William had to keep the plane flying. Confident and in control, William did just that.

“We’re just so thrilled, just so happy to plug him into his dream,” Danica said. “To be in the plane with him, seeing him flying, just seeing him totally locked in, that's all a parent can wish for.”

Flying lessons cost between $300 and $500 depending on airtime, and William averages about two lessons a month. That can strain the family budget for Denice, a teacher at Florida Virtual School, and Kevin, who is retired after 22 years in the U.S. Army.

“It’s not like we’re rolling in the dough,” Denice said. “The scholarship makes this possible. If we didn't have that scholarship, how many flights would he get? Probably not as many as he's getting now.

“I'm thrilled to be in Florida, because there's so much parental choice here. Not only do parents have choices, but then they can branch out and get some financial support from the state for those choices. Amazing. It's awesome.”

Every family in Florida that receives an education choice scholarship uses it in their own, unique way. Denice encourages parents to be as forward-thinking as possible, to merge education and interests and work toward a goal.

“I would like more people to think beyond where their kid is right now, but what are they good at. Really invest in that and tune in and give them the most experience as you can,” she said. “To me, that's what the scholarship money is for, branching out, tap into your kids’ interests because you never know what can happen.”

As Denice said, the sky is the limit.

Education Next published a piece recently by Holly Korbey called The Tutoring Revolution, which reads in part:

Recent research suggests that the number of students seeking help with academics is growing, and that over the last couple of decades, more families have been turning to tutoring for that help. Private tutoring for K–12 students has seen explosive growth both nationally and around the globe. Between 1997 and 2022, the number of in-person, private tutoring centers across the United States more than tripled, concentrated mostly in high-income areas like Brentwood. Many students are also logging onto laptops to get personalized digital tutoring, with companies like WyzAnt and Outschool reporting they’ve enrolled millions of students for millions of hours in private, video-based learning sessions that students access conveniently from home. Market reports estimate the digital tutoring market was worth $7.7 billion globally in 2022, with projections of a compound annual growth rate of nearly 15 percent from 2023 to 2030.

Recall as well one of the most fascinating parts of Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast series wherein Lacey Robinson, a veteran teacher in inner-city public schools described taking a teaching position in the suburbs. Robinson wanted to learn what the suburban schools were doing to teach literacy to upper-income students, and then bring it back to the inner-city schools. She discovered that the suburban schools were providing their students with approximately nothing:

“They were learning to decode at home with tutors. I know, because I became one of them.”

If you speak with or poll American suburbanites, they have traditionally expressed a fair degree of confidence in their public schools, which they tended to describe as either “okay” or “good.” Monitor their actions over time, however, and you see that they placed a greater and greater reliance upon tutoring. Most were enrolling their children in public schools, but they were relying upon them less and less and upon tutoring and other private enrichment spending more and more.

In 2015 Wired ran an article called The Techies Who Are Hacking Education by Homeschooling Their Kids. The unstated background message of this article: Silicon Valley families had decided that the time opportunity cost of enrolling their children in a school, even a public school they had already paid for with their taxes, was too high. Key quote:

“There is a way of thinking within the tech and startup community where you look at the world and go, ‘Is the way we do things now really the best way to do it?’” de Pedro says. “If you look at schools with this mentality, really the only possible conclusion is ‘Heck, I could do this better myself out of my garage!’”

Your garage, and perhaps your local Kumon, museums and hackerspaces. Early during the pandemic, Silicon Valley families created a Facebook group called “Pandemic Pods” with spontaneous order scratch to a very itchy group of American families.

The COVID-19 pandemic opened the eyes of many families regarding how much responsibility they should take for the education of their children: all of it. The public school system operates in the interests of its major shareholders (i.e., those deciding school board elections). Broadly speaking, mere taxpayers and families don’t qualify. One can describe the public school system as broken, but you can more precisely observe that it is operating as intended.

If you doubt that last statement, I invite you to attempt to lobby for a meaningful change in the way the public school system operates. You’ll meet all kinds of interesting people. Sadly, most of them will be eager to die on a hill defending the K-12 status quo.

If someone purposely designed an education system to generate inequality, they would have some difficulty exceeding the ZIP code assignment plus tutoring for those who can afford it status quo. The question moving forward is not whether we are going to have more a la carte multi-vendor education. The question is what, if anything, we are willing and able to do to distribute that opportunity.

Harvard professor Roland Fryer took to the pages of the Wall Street Journal recently to urge lawmakers and advocates to reinvigorate the drive to Milton Friedman’s vision of a dynamic demand-drive K-12 system:

Today’s school-choice ecosystem, which one might refer to as “market lite,” has helped thousands of families. But millions are waiting, and current choice programs operate within the same inadequate framework. Increasing choice on the margin through partial vouchers, magnet school or other measures has yielded disappointing results because of an imperfectly competitive market. Real competition doesn’t mean entering a lottery to attend a charter school or providing vouchers worth only a fraction of public-school funding.

Only a small number of states have adopted enough “market lite” proposals, in combination, to begin to realize the potential of an education system driven by families and supply by educators. Fryer puts his finger on the problem directly:

School choice as currently implemented is more patchwork than panacea. It’s like getting to pick between a government-run cafeteria and an alternative where the line is long and, more often than not, the dish you were hoping for has run out by the time you get to the front. Friedman envisioned a nation of all-you-can-eat buffets.

Every waitlist, in other words, is a policy failure. Fryer expresses enthusiasm for education savings account programs, and ESAs are indeed potentially less limited by supply constraints. The details however matter greatly: formula funded ESA programs have the transformative potential Fryer extols, whereas a program limited by annual appropriation seems likely to produce the dreaded waitlists.

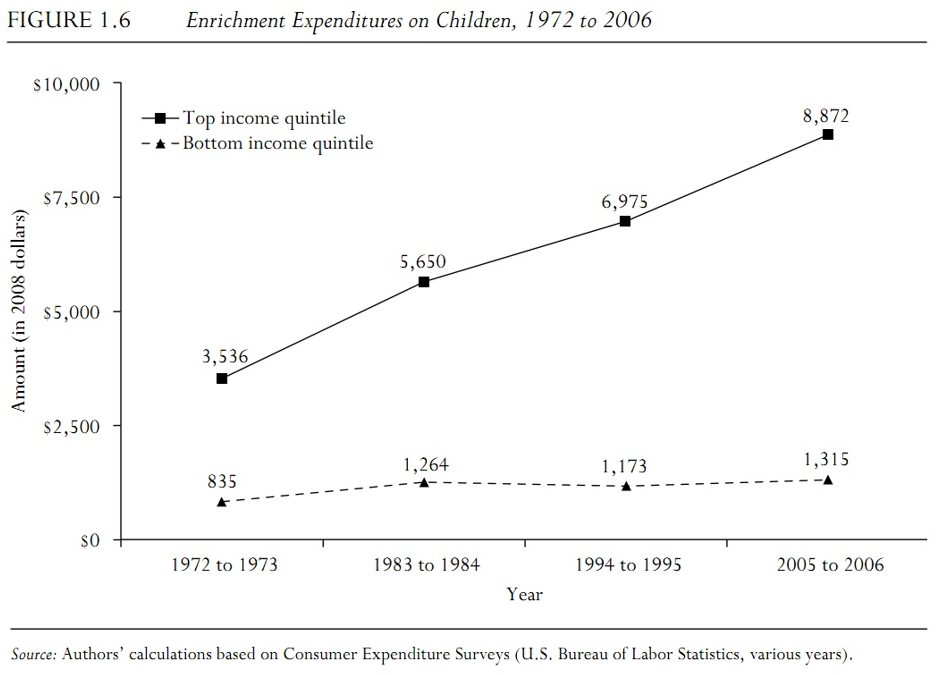

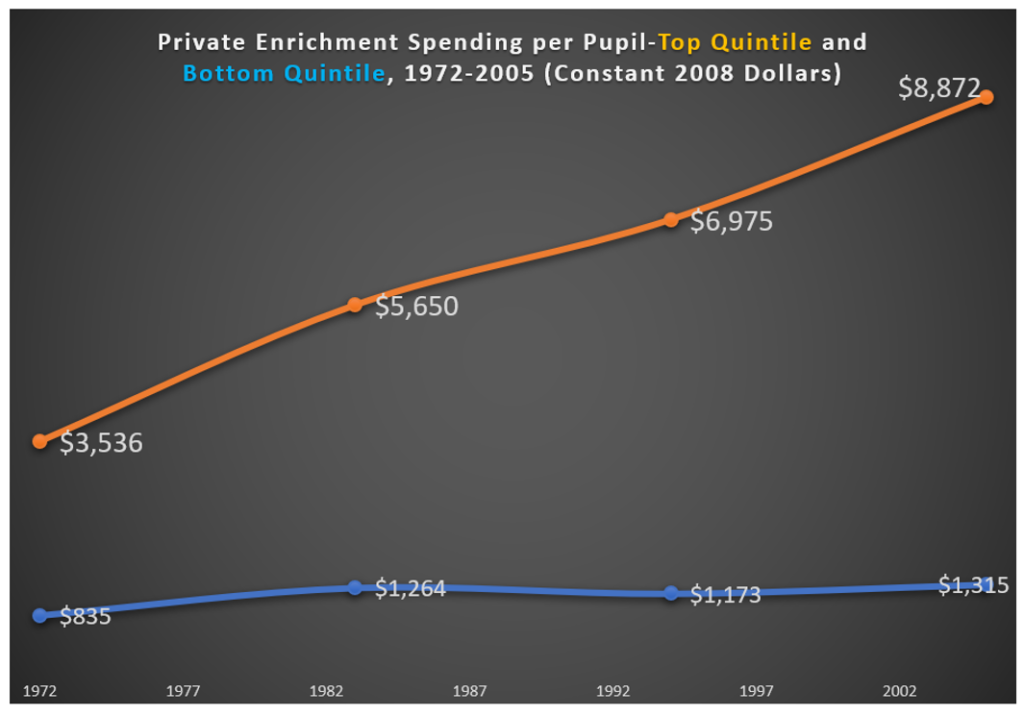

The reality is that upper-income Americans have been investing in multi-vendor education at a growing rate for decades. Private spending on enrichment activities, including tutors, Kumon, summer camps, private lessons, Mathnasium, club sports and far more.

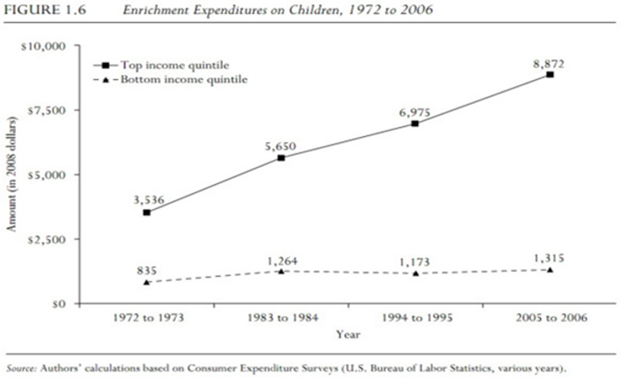

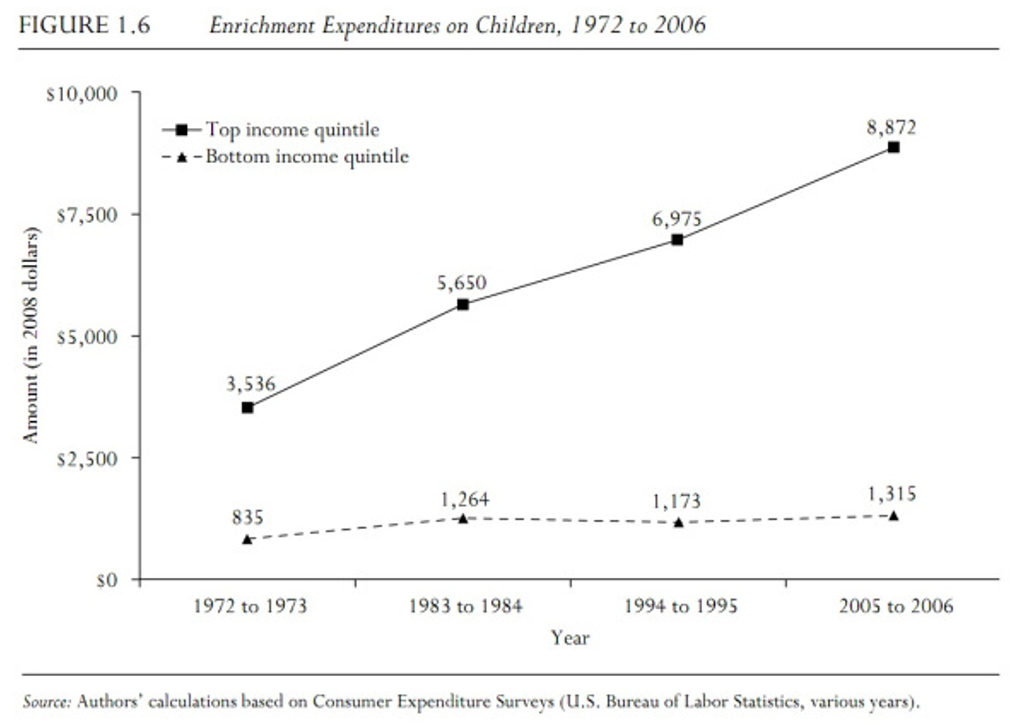

If you’ve ever felt exhausted by driving your kids around after school, or compared notes with other parents on this, you have been a part of this trend. Scholars have documented upper-income Americans spending approximately $9,000 per child per year on enrichment activities. How much credit do leafy suburban schools deserve for their monopoly on non-embarrassing scores on international achievement exams? No one can say for sure, but it may not be as much as commonly assumed.

The significance of the enrichment trend became apparent only after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Advantaged American families still paid exorbitant mortgage ransoms to access the best public schools, but they were not entirely relying upon those schools. Increasing numbers of families have correctly discerned that the opportunity cost of attending a district is simply too high.

Demand driven education is here — it’s just not evenly distributed. Policymakers in some states have democratized the opportunity to participate through ESAs, which have the transformative potential Fryer extols. Elite families will continue to engage in multi-vendor education with or without ESAs, but states with well-designed programs will share such opportunities across society. The future is indeed here; will we distribute it?

SailFuture, a private high school, started as a mentoring program for at-risk youth by teaching them maritime skills through sailing adventures. It recently was named as one of 32 semifinalists for the $1 million Yass Prize to be awarded in December.

Consulting firm Tyton Partners, in collaboration with the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust, today released a new report, Choose to Learn 2022, that looks at data collected from more than 3,000 K-12 parents and more than 150 K-12 suppliers across all 50 states in the United States.

The report finds that 52% of parents now prefer to direct and curate their child’s education rather than rely on their local school system, and 79% of parents believe learning can and should happen everywhere as opposed to in school alone. Data shows that parents want experiences that make their child happy, above all else, by reflecting their child’s interests and providing individual academic support. However, despite all parents reporting similar goals for their children, regardless of demographics, the study reveals gaps in program participation across income and race. For example, children from underserved backgrounds are nearly two times less likely to participate in learning outside of school than their peers.

Choose to Learn 2022 explores the variety of K-12 options now available to families – inclusive of both in- and out-of-school educational offerings – and how this ecosystem can better reflect families’ broader aspirations for their children. The publication follows recent findings from Tyton Partners’ School Disrupted 2022 series, which highlighted the near 10-percent decline in district public school enrollment due to the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In viewing K-12 through a broad lens, we set out to better understand the issues impacting every family, including more than forty million parents who send their children to public school,” according to Christian Lehr, Senior Principal at Tyton Partners and the lead author of Choose to Learn 2022. “Relative to issues of equity and access, our local public districts play a crucial role for K-12 families. At the same time, families crave a wide variety of learning experiences. It is in this spirit that we examined parents’ aspirations at the intersection of in- and out-of-school learning, and ask: How can the K-12 sector deliver a stronger union of academic, extracurricular, and personal outcomes for all families, regardless of life or economic circumstances?”

Based on these findings and more identified in this study, it is clear now more than ever that parents want an education centered on the needs of their child, yet there is continued work that needs to be done to bridge the gap between aspiration and reality. It is incumbent upon the K-12 system of policymakers, system leaders, and suppliers to introduce new experiences, choices, and outcomes into local school districts and catalyze the growth of programs outside of school and across all demographics.

Choose to Learn 2022 underscores the need for the K-12 system to move towards a more student-centric future and helps readers understand how to:

“We are honored to have the opportunity to drive this pivotal conversation forward, alongside our partners, the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust,” according to Adam Newman, Founder and Managing Partner at Tyton Partners. “There is a clear call for us to collectively build towards a more student-centered future in K-12 education.”

To view the findings and learn more about this study, download Choose to Learn 2022 on the Tyton Partners website.

Among a plethora of “experiences” offered by Airbnb is whale watching, an opportunity available to those with the interest and ability to pay rather than ZIP code.

We who live in the Grand Canyon state love a good adventure. At any given moment, we could be checking out a giant meteor crater, crawling around in long extinct lava tubes, touring ancient Native American constructions, or hiking in petrified forests.

When we venture out of state, lots of us head to San Diego. The Pacific Ocean, beaches, the U.S.S. Midway and more can make for a fun weekend. You can see how much fun this can be on the “Experiences” button on the Airbnb website.

If you squint hard enough, you just might catch a glimpse of the future of K-12 education.

Airbnb is best known for connecting vacationing renters with people who make their property available for rent. It’s an example of voluntary exchange at its finest; the system gives opportunities for people to stay at a wider variety of properties while allowing those with property the opportunity to earn income.

A more recent feature on Airbnb allows viewers to purchase “experiences.” You can click on the link above and enter “San Diego” in the “experiences” bar to give this new feature a test drive.

Members of the Ladner clan did this recently, choosing to go on a beach walk with a marine biologist, walking shelter dogs on the beach and taking a whale watching tour. The universe of choices is far broader than this, offering a huge variety of tours on land, sea and air, arts activities, physical activities, culinary experiences and much more.

As is ubiquitous these days, users rate the experience as a resource for future users. Experiences operate on voluntarism. Your interest and ability to pay determine the experiences you select rather than your ZIP code. Needless to say, those who participate can learn a lot and have a lot of fun.

The chart below demonstrates the trend of upper-income Americans spending more and more money on enrichment activities for their children.

I can hear grumbling among my traditionally minded readers. They – you? – are thinking that while possibly educational, a random collection of experiences doesn’t necessary add up to an education per se. Of course, this is true.

I can hear grumbling among my traditionally minded readers. They – you? – are thinking that while possibly educational, a random collection of experiences doesn’t necessary add up to an education per se. Of course, this is true.

Keep in mind, though, that a frighteningly large percentage of students sitting through 13 years of public education aren’t receiving an education either. It isn’t difficult to imagine successfully sequencing learning experiences into a logical course of learning, which is why some see the future of education harking back to Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts and the earning and awarding of badges for course completion.

Nor is it difficult to imagine putting it all in an Airbnb style app.

As the chart shows, multi-vendor education has been growing rapidly among upper-income American families for decades. If you’ve been to a cocktail party in the last 15 years, you’ve heard some version of “I’m so exhausted by driving Madison around to X, Y and Z after school” story.

That story is multi-vendor education, and in many cases features pandemic pods, which originated years ago with Silicon Valley parents who figured out they could do more of it if their kids weren’t in a traditional school.

The ever-increasing spending of upper-income Americans on enrichment activities doubtlessly contributes to the fact that their children do quite will on international exams. After all, top quintile income American families didn’t spend, on average, $8,872 in 2006 on Kumon, etc., to lower their golf handicap.

By necessity, the COVID shutdown forced a great many parents to scramble to keep their children academically engaged. Multi-vendor education has worked well for upper-class Americans, and it should be the shape of things to come to allow everyone to participate by giving them control over their K-12 resources.

Pandemic pods were all the rage in last week’s news stories as parents around the country began organizing into micro-schools. It is indeed a fascinating thing to watch, but Amara’s law should be kept in mind.

Stanford computer scientist Roy Amara is credited with the theory that “we tend to overestimate the impact of a new technology in the short run, but we underestimate it in the long run.” So, too, will it likely be with pandemic pods. Matters have been trending in this direction for decades with well- to-do America. The question at hand is what sort of opportunities do children whose parents are not well-to-do deserve?

“Marriage of convenience” is a term one might use to describe the relationship between upper-crust America and public education. That class of Americans get the best of everything that public education has to offer, and generally pay more than anyone else for it in the form of higher state and local taxes. Even upper-income families who enroll their children in public schools, however, do not put all their eggs in that basket.

So, the pandemic strikes, impromptu distance learning goes somewhere on the poor to catastrophically poor spectrum. Ineffective COVID-19 tests get released and recalled and good tests are hamstrung by red tape. Americans are told not to wear masks and then to wear masks. A certain expression about a decapitated chicken comes readily to mind.

Uruguay safely reopened their schools in June, but it may be beyond the ken of Americans.

Meanwhile, education unions have produced lists of policy demands, many unrelated to schooling, and are filing lawsuits to counteract state and district mandates. Is it any wonder a growing number of parents have decided to take matters into their own hands?

Upper-income Americans use public schools, but they stopped relying upon them solely long ago. This chart shows the trend in private spending on student enrichment activities by family income quartile (top and bottom quartiles, respectively).

“Do it yourself” education is old hat for upper-income Americans. Multiple service-provider education has been the norm for upper quintile Americans for decades. Kumon, Mathnasium, club sports, tutors, college entrance exam coaches – you name, it, they have been shelling out money for it. Podding up with others and hiring a teacher during a period when the country seems determined to slip into pandemic dysfunction is an entirely reasonable next step given the circumstances.

“Do it yourself” education is old hat for upper-income Americans. Multiple service-provider education has been the norm for upper quintile Americans for decades. Kumon, Mathnasium, club sports, tutors, college entrance exam coaches – you name, it, they have been shelling out money for it. Podding up with others and hiring a teacher during a period when the country seems determined to slip into pandemic dysfunction is an entirely reasonable next step given the circumstances.

Amara’s law seems to apply. Pandemic pods are not going to “destroy public education,” as constitutional funding guarantees are safely enshrined in state constitutions. Upper-income families have been hybrid homeschooling on their own time for decades. The danger to traditional schooling, if any, lies in that some growing percentage of them may notice the opportunity time cost of traditional schooling.

The longer-term significance of this episode, however, seems likely to be an increased culture of self-reliance and do-it-yourself education. The chart shows this phenomenon is not new; pandemic pods are simply the latest incarnation of a long-established trend.

We cannot (nor should not) prevent families from enrolling their children in Kumon, club sports, or indeed, pandemic pods. We can and should, however, allow disadvantaged families the option of using state-provided funds to enable their children to participate.

In other words, the worrying trend in the chart is not the steepness of the top line but rather the flatness of the bottom line.

Andrew Rotherham recently proposed that America’s public schools remain open this summer. Many impediments stand in the way of this, including numerous laws and many thousands of contracts. A common reaction to Rotherham’s summer school proposal looks something close to “that’s not going to happen.”

Andrew Rotherham recently proposed that America’s public schools remain open this summer. Many impediments stand in the way of this, including numerous laws and many thousands of contracts. A common reaction to Rotherham’s summer school proposal looks something close to “that’s not going to happen.”

This was a common reaction to lost instruction time during the 2018 teacher strikes as well.

One group of students – early elementary school children struggling to read – will face serious long-term detriments to chalking the 2020 pandemic up to an act of God. These kids may or may not need and may not be able to get summer school, but they certainly need solutions. These students have a literacy acquisition window, and some of them aren’t going to have their needs met otherwise.

The Big Picture

The United States has an active market in education enrichment, and well-to-do American families have been spending more and more on it.

It’s a safe bet that many students learn to read at home, but others are much more dependent on school to equip them with academic knowledge and skills. Students in advantaged households are likely to fare better during the current closures as well, due to greater access to a variety of resources.

Why It Matters

Learning to read is similar neurologically to learning a foreign language. The reason, for instance, that Arnold Schwarzenegger still speaks English with a heavy Austrian accent despite having lived in the United States for many decades is because he learned English relatively late in life. He could have become a more fluent English speaker, but only with a much greater effort compared to what would have been required if he had learned when he was younger.

If students fail to learn to read in the early grades, they often struggle as grade-level material advances. Such students will describe themselves as “bored,” but “discouraged” might be a better description. They tend to start dropping out of school in large numbers starting in eighth grade. You can test the literacy skills of state prisoners and the news is grim there as well. Literacy becomes much more difficult after age 10.

What to Do?

If summer school for all is either undesired or undoable, strong action is nevertheless called for among young students struggling with reading. Florida already had established a modestly funded ($500) education scholarship account for struggling readers. This program could be expanded to help facilitate the creation of summer reading camps if the pandemic persists.

Local education agencies might create summer schools focused on struggling readers. Perhaps Florida Virtual School could help such students. The clock is ticking for these students, and in early literacy, neglect is malign rather than benign.