Jordan Glen School started in 1974 on 20 acres of woods in the small town of Archer near Gainesville. Owner Jeff Davis, a former public school teacher, moved to Florida from Michigan to start a school that allowed students more freedom. Today it continues to thrive, thanks in part to education choice scholarships. Photo by Ron Matus

ARCHER, Fla. – Archer is a crossroads community of 1,100 people 15 minutes from the college town of Gainesville, but far enough away to have its own quirky identity. It’s surrounded by live oak-studded ranch land but calling it a “farm town” doesn’t ring right. When railroads ruled the Earth, Archer was a whistle stop on the first line connecting the Atlantic to the Gulf. In the late 1800s, T. Gilbert Pearson, co-founder of the National Audubon Society, roamed the woods here as a kid, skipping school to hunt for bird eggs. A century later, rock ‘n roll icon Bo Diddley spent his golden years on the outskirts.

So, let’s just say Archer is a neat little town. And maybe it’s fitting that for half a century, it has been home to a neat little private school that doesn’t fit into any boxes, either.

Jordan Glen School got its start in 1974, when former public school teacher Jeff Davis moved down from Michigan. In the late 1960s, Davis became disillusioned with teaching in traditional schools. In his view, students were respected too little and labeled too much.

“Back in the day, I would have been labeled ADHD. I hated school,” he said. “I never met a teacher that took a personal interest in me.”

As a teacher, he saw a system that was “too constricting.”

“There was just a general distrust of children, like they were going to do something bad,” he said. Education “doesn’t have to be rammed down your throat.”

Davis migrated to what was, more or less, a “free school,” with 50 students on a farm near Detroit. Today we’d call it a microschool.

In the 1960s, hundreds of these DIY schools emerged across America, propelled by an upbeat vision of education freedom inspired by the counterculture. Davis said the Upland Hills Farm School was a free school, more or less, because while its teachers were “long-haired” and “hippie-ish,” the school had more structure and rigor than free school stereotypes would suggest.

Davis thought the Gainesville area would be a good place to start a similar school. It had a critical mass of like-minded folks. So, in 1973, he and his family bought 20 acres of woods off a dirt road in Archer. Not long afterward, they invited a little school called Lotus Land School, then operating out of a community center in Gainesville, to move to their patch in the country. Today we’d call Lotus Land a microschool, too.

It was also, more or less, a free school. Davis described the teachers and families as “love children” and “free spirits,” but in many ways, their approach to teaching and learning was mainstream. A decade later, he changed the name. “I thought people would think it was a hippie dippy school, and I knew it was more than that,” he said.

Lotus Land became Jordan Glen. The school was named after the River Jordan, after some parents and teachers suggested it, and after basketball legend Michael Jordan, because Davis was a fan.

Fast forward a few more decades, and Jordan Glen School is thriving more than ever.

It now serves more than 100 students in grades PreK-8, some of whom are the second generation to attend. Nearly all use Florida’s education choice scholarships. Actor Joaquin Phoenix is among Jordan Glen’s alums. So is CNN reporter and anchor Sara Sidner.

Jordan Glen is yet more proof that education freedom offers something for everyone and that its roots are deep and diverse. Ultimately, the expansion of learning options gives more people from all walks of life more opportunity to educate their children in line with their visions and values.

“There is something about joy and happiness that makes people uneasy and a bit insecure,” Davis wrote in a 2005 column for the local newspaper, entitled “Joyful Learning is the Most Valuable Kind.” “If children are enjoying school so much, they must not be doing enough ‘work’ there.”

“Children at our school,” he wrote, “love life.”

A peacock, one of two dozen that roam the Jordan Glen School campus, watches students at play. Photo by Ron Matus

The Jordan Glen campus includes a handful of modest buildings. It’s still graced by a dirt road and towering trees. It’s also home to two dozen, free-roaming peacocks. They’re the descendants of a pair Davis bought in 1975 because they were beautiful and would eat a lot of bugs.

Given that backdrop, it’s not surprising that many families describe Jordan Glen as “magical.”

Alexis Hamlin-Vogler prefers “whimsical.” She and her husband decided to enroll their children, Atticus, 14, and Ellie, 8, in the wake of the pandemic.

“They’re definitely outside a lot,” she said of the students. “They’re climbing trees. They’re picking oranges.” When it rained the other day, her daughter and some of the other students, already outside for a sports class, got a green light to play in it and get muddy.

Another parent, Ilia Morrows, called Jordan Glen a “little unicorn of a school.”

Like Hamlin-Vogler, Morrows enrolled her kids, 11-year-old twins Breck and Lucas, following the Covid-connected school closures. She thought they’d stay a year, then return to public school. But after a year, they didn’t want to go back. “They had a taste of freedom,” she said.

For many parents, Jordan Glen hits a sweet spot between traditional and alternative.

On the traditional side, Jordan Glen students are immersed in core academics. They take tests, including standardized tests. They get grades and report cards. They play sports like soccer and tennis, and they’re good enough at the latter to win the county’s middle school championship. Many of them move on to the area’s top academic high schools.

But Jordan Glen also does a lot differently.

Students spend a lot of time outdoors at Jordan Glen School. Activities include archery, gardening and sports. Photo by Ron Matus

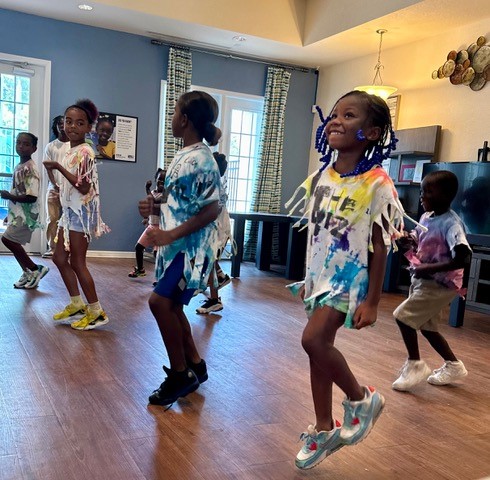

The students are grouped into multi-age and multi-grade classrooms. They choose from an ever-changing menu of electives. Many of those classes are taught by teachers, but some are taught by parents (like archery, gardening, and fishing), and some by the students themselves (like soccer, dance, and book club). The youngest students also do a “forest school” class once a week.

The school also emphasizes character education.

The older students serve as mentors for the younger students. They’re taught peer mediation so they can settle disputes. Every afternoon, they clean the school, working as crew leaders with teams of younger students. Their “Senior Class Guide” stresses nothing is more important than “caring about others.”

“The way the older kids take care of the younger kids, it’s very noticeable. They are genuinely caring,” Morrows said. At Jordan Glen, “they teach community. They teach being a good human.”

“My favorite thing is that most kids really get a good sense of self and self-confidence at this school,” Hamlin-Vogler said. “Some people say, ‘Oh, that’s the hippie school.’ But the students have a lot of expectations and personal accountability put on them.”

Hamlin-Vogler said without the education choice scholarships, she and her husband wouldn’t be able to afford the school. Hamlin-Vogler is a hairdresser. Her husband is a music producer. Before Florida made every student eligible for scholarships in 2023, they missed the income eligibility threshold by $1,000. Her parents were able to assist with tuition in the short term, but that would not have been sustainable.

Her family harbors no animus toward public schools. Atticus attended them prior to Jordan Glen, and he’s likely to be at a public high school next fall. Ellie, meanwhile, thinks she might want to try the neighborhood school even though she loves Jordan Glen in every way, and Hamlin-Vogler said that would be fine.

After Ellie described how much fun she had playing in the rain, though, Hamlin-Vogler had to remind her, “You might not get to do that at another school.”

When I think about the state of public education in Florida, I recall a song from “The Wiz,” the 1978 film reimagining of “The Wizard of Oz,” where Diana Ross sang, “Can’t you feel a brand new day?”

It’s a brand new day in our state’s educational history. Parents are in the driver’s seat deciding where and how their children are educated, and because the money follows the student, every school and educational institution must compete for the opportunity to serve them.

Public schools are rising to meet that challenge.

For the past year, helping them has been my full-time job.

Today, 27 of Florida’s 67 school districts have contracted with Step Up For Students to provide classes and services to scholarship students, and another 10 have applied to do so.

That’s up from a single school district and one lone charter school this time a year ago.

This represents a seismic shift in public education.

For decades, a student’s ZIP code determined which district school he or she attended, limiting options for most families. For decades, Florida slowly chipped away at those boundaries, giving families options beyond their assigned schools.

Then, in 2023, House Bill 1 supercharged the transformation. That legislation made every K-12 student in Florida eligible for a scholarship. It gave parents more flexibility in how they can use their child’s scholarship. It also created the Personalized Education Program (PEP), designed specifically for students not enrolled in school full time.

This year, more than 80,000 PEP students are joining approximately 39,000 Unique Abilities students who are registered homeschoolers. That means nearly 120,000 scholarship students whose families are fully mixing and matching their education.

Families are sending the clear message that they want choices, flexibility, and an education that reflects the unique needs and interests of their children.

Districts have heard that message.

Parents may not want a full-time program at their neighborhood school, but they still want access to the districts’ diverse menu of resources, including AP classes, robotics labs, career education courses, and state assessments. Families can pay for those services directly with their scholarship funds, giving districts a new revenue stream while ensuring students get exactly what they need.

In my conversations with district leaders across the state, they see demand for more flexible options in their communities, and they’re figuring out how to meet it.

For instance, take a family whose child is enthusiastic about robotics. In the past, their choices would have been all-or-nothing. If they chose to use a scholarship, they would gain the ability to customize their child’s education but lose access to the popular robotics course at their local public school. Now, that family can enroll their child in a district robotics course, pay for it with their scholarship, and give their child firsthand technology experience to round out the tutoring, curriculum, online courses and other educational services the family uses their scholarship to access.

Families can log in to their account in Step Up’s EMA system, find providers under marketplace and select their local school district offerings under “contracted public school services.” School districts will get a notification when a scholarship student signs up for one of their classes. From large, urban districts like Miami-Dade to small, rural ones like Lafayette, superintendents are excited to see scholarship students walk through their doors to engage in the “cool stuff” public schools can offer. Whether it’s dual enrollment, performing arts, or career and technical education, districts are learning that when they open their arms to families with choice, those families respond with enthusiasm.

Parents are no longer passive consumers of whatever system they happen to live in. They are empowered, informed, and determined to customize their child’s learning journey.

This is the promise of a brand new day in Florida education. For too long, choice has been framed as a zero-sum game where if a student left the public system, or never even attended in the first place, the district lost. That us-versus-them mentality is quickly going the way of the Wicked Witch of the West. What we are witnessing now is something far more hopeful: a recognition that districts and families can be partners, not adversaries, in building customized learning pathways.

The future of education in Florida is not about one system defeating another. It is about ensuring families have access to as many options as needed, regardless of who delivers them.

As Diana Ross once sang, “Hello world! It’s like a different way of living now.” It has my heart singing so joyfully.

Berkeley law professors Jack Coons (left) and Stephen Sugarman described what we now call education savings accounts - and a system of à la carte learning - in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice.”

John E. Coons was ahead of his time.

Decades before the term “education savings account” became an integral part of the education choice movement, the law professor at the

Jack Coons, pictured here, co-authored "Education by Choice" in 1978 with fellow Berkeley law professor Stephen Sugarman.

University of California, Berkeley, and his former student, Stephen Sugarman, were talking about the concept. In their 1978 book, “Education by Choice: The Case for Family Control,” the two civil rights icons envisioned a model drastically different from the traditional one-size-fits-all, ZIP code-based school system inspired by the industrial revolution:

“To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead, some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.”

Coons and Sugarman also predicted charter schools, microschools, learning pods and education navigators, although they called them by different names.

Fast forward to Florida today, where the Personalized Education Program, or PEP, allows parents to direct education savings accounts of about $8,000 per student to customize their children’s learning. Parents can use the funds for part-time public or private school tuition, curriculum, a la carte providers, and other approved educational expenses. PEP, which the legislature passed in 2023 as part of House Bill 1, is the state’s second education savings account program; the first was the Gardiner Scholarship, now called the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities, which was passed in 2014.

Coons, who turned 96 on Aug. 23, has been a regular contributor to Step Up For Students' policy blogs over the years. Shortly after the release of his 2021 book, “School Choice and Human Good,” he was featured in a podcastED interview hosted by Doug Tuthill, chief vision officer and past president of Step Up For Students.

“It is wrong to fight against (choice) on the grounds that it is a right-wing conspiracy,” said Coons, a lifelong Catholic whom some education observers describe as “voucher left.” “It’s a conspiracy to help ordinary poor people to live their lives with respect.”

“It is wrong to fight against (choice) on the grounds that it is a right-wing conspiracy,” said Coons, a lifelong Catholic whom some education observers describe as “voucher left.” “It’s a conspiracy to help ordinary poor people to live their lives with respect.”

In 2018, Coons marked the 40th anniversary of “Education by Choice” by reflecting on it and his other writings for NextSteps blog.

He said he hopes his work will “broaden the conversation” about the nature and meaning of the authority of all parents to direct their children’s education, regardless of income.

“Steve (Sugarman) and I recognized all parents – not just the rich – as manifestly the most humane and efficient locus of power,” he wrote. “The state has long chosen to respect that reality for those who can afford to choose for their child. ‘Education by Choice’ provided practical models for recognizing that hallowed principle in practice for the education of all children. It has, I think, been a useful instrument for widening and informing the audience and the gladiators in the coming seasons of political combat.”

Utah students celebrate National School Choice Week at the state capitol. Photo courtesy of National School Choice Week

In the 1949 Looney Tunes short “Mouse Wreckers,” two mind-manipulating rodents named Hubie and Bertie try to chase award-winning mouser Claude Cat out of his home by driving him crazy. They bang him on the head with a fireplace log, throw a stick of dynamite on Claude’s nap cushion, and even frame him for antagonizing a bulldog, who pummels him.

The last straw is when the mice nail all the living room furniture to the floor while Claude is napping. Thinking he is stuck on the ceiling, he jumps up to what he thinks is the floor. When he opens a bottle of nerve tonic, all the liquid “rises” to what Claude thinks is the ceiling.

The last straw is when the mice nail all the living room furniture to the floor while Claude is napping. Thinking he is stuck on the ceiling, he jumps up to what he thinks is the floor. When he opens a bottle of nerve tonic, all the liquid “rises” to what Claude thinks is the ceiling.

Similar confusion over ceilings and floors is at the heart of a legal battle in Utah, where a trial court judge ruled that the legislature figuratively bumped its head on the state constitution when it passed the Utah Fits All Scholarship Program in 2023.

Third District Judge Laura Scott wrote in her ruling that the state constitutional mandate that the Legislature establish and maintain a public education system is a ceiling. The state cannot create alternatives. If it were a floor, the legislature would have the authority to create other publicly funded education programs in addition to the public school system.

In separate appeals filed last week, the Utah Attorney General’s Office, along with two parents represented by the Institute for Justice and EdChoice Legal Advocates, each say that the judge erred in calling the constitution’s education clause a ceiling. They argue it is a floor.

“The legislature is already meeting its constitutional mandate to provide a free public education system devoid of sectarian control and open to all children. Plaintiffs do not argue otherwise,” the state’s appeal reads. “The district court recognized that Plaintiffs’ Article [X] claim fails as a matter of law if the educational provisions set a floor rather than a ceiling on legislative power.”

However, the lower court “created new limitations on the Legislature out of whole cloth,” according to the parents’ appeal.

The Utah Fits All Scholarship Program took effect in the fall of 2024 and gives eligible K-12 students up to $8,000 a year for private school tuition and other approved costs. In the first year, more than 27,000 students applied for 10,000 available scholarships. Unlike in South Carolina, where families were left scrambling last year after the state Supreme Court struck down its scholarship program, Utah families are allowed to continue using the program while the case is under appeal and will likely to be able to finish out the school year.

One of two cases that the judge relied on was Bush v. Holmes, which the parents’ attorneys called “the sole outlier” on the list of court decisions from other states.

The 1999 complaint challenged the Florida Opportunity Scholarship Program. In it, the Florida Supreme Court ruled in 2006 that the program violated the constitution’s provision requiring a “uniform” system of public schools for all students.

Scott wrote that the Florida provision “acts as a limitation on legislative power” and that in spelling out how something must be done, it effectively forbids it from being done differently.

The Utah parents’ attorneys called Florida’s provision “unique” and different from the broader language in the Utah Constitution.

“But even if Florida had analogous language to Utah’s Education Article — and it does not — Holmes is a singularly unpersuasive decision. One need only compare the majority and dissenting opinions to appreciate how flawed the majority’s reasoning was and how glaring are its many errors.”

Maria Ruiz and thousands of other families could lose their ability to choose schools that best fit their children’s educational needs if the Utah Supreme Court upholds a lower court ruling striking down the Utah Fits All ESA program. Photo courtesy of Institute for Justice

For the thousands of families who relied on the program, the stakes couldn’t be higher as they now find themselves under the shadow cast by the district court’s order just months before a new school year begins.

“In the interest of removing that shadow as soon as practicable so that Utah families can plan for their children’s upcoming academic year without disruption, Parents ask for this Court’s review,” the attorneys wrote in the parents’ appeal.

At the end of Mouse Wreckers, Claude races screaming from the house and clings, trembling, to a tree. The mice roast cheese and congratulate themselves.

“That upside-down room was the pièce de résistance,” Bertie says to a laughing Hubie.

Attorneys defending Utah’s scholarship families hope the state’s high court will flip the state constitution right-side up.

Star Lab students learn through creative activities like this fishing game. Photo courtesy of Star Lab.

SARASOTA, Fla. – Alison Rini thought her destiny was to be the principal at a traditional public school. She had been the principal at a charter school, the assistant principal at a Title I district school, and the assistant principal at a magnet school for gifted students.

But in the wake of Covid, Rini began to feel “adrift.” The system, in her view, proved incapable of helping students, particularly low-income students, overcome the academic and behavioral deficits left by distance learning. Some students were being promoted, even though they weren’t ready. Others were being labelled disabled, even though they weren’t.

“My path wasn’t leading to where I thought it would,” Rini said. “It felt like they just wanted me to grease the wheels to keep them turning. And people were getting chopped up in the gears.”

“I just felt there’s got to be a better way.”

In 2023, Rini took a leap of faith, one that is becoming common for public school teachers in school-choice-rich states like Florida.

She decided to start her own school.

For other recent examples, see here, here, here, here, and here.

With help from The Drexel Fund, a philanthropy that helps promising new private schools start and/or grow, Rini took a year to plan. She visited successful schools across the country; acquired deeper knowledge about the business side of running a school; and mapped out exactly what she wanted to create. Her vision was based on 20-plus years of learning the best approaches from teaching in all types of schools, from New York City to the Virgin Islands to the Gulf Coast of Florida.

The result is Star Lab, a private microschool that opened last fall with a handful of kindergartners and is now set to expand. It’s housed in the recreation center of an oak-graced public housing complex in Newtown, a historic Black neighborhood in Sarasota.

Watching students walk up on the first day of school in their Star Lab shirts was “an out of body experience,” Rini said.

“It was just such a dream come true,” she said. “And this year has been such a joy, to behold the power of just tailoring something around kids – not around adults, not around the system.”

Star Lab is a rich blend of philosophies and practices that reflect Rini’s background in education and neuroscience. (Rini earned a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience and behavior, and master’s degrees in elementary education and education leadership, all from Columbia.)

Star Lab’s approach to reading instruction is grounded in “science of reading” research. It employes hands-on Montessori materials to help students better grasp some academic concepts at their own pace. It embraces the Finnish approach to student movement, which sees frequent play breaks as optimal for learning. It also emphasizes individualized lessons, mastery learning, lots of direct instruction, and progress monitoring via a custom-built dashboard.

“We're not just educating,” the school website says, “we're preparing future leaders, innovators, and global citizens who are as healthy and mindful as they are intellectually empowered.”

Exercise and mindfulness are an important part fo the daily routine at Star Lab. Photo courtesy of Star Lab

Every morning at Star Lab starts with 25 minutes of exercise and five minutes of “mindfulness” activities. Monday through Thursday, the students are immersed in core academics. Fridays are for group activities like drama, field trips, and guest speakers.

Rini guarantees parents that Star Lab students will perform at or above grade level in reading and math. Most of the students in the neighborhood are not at that level, which is why Rini chose to be here. According to the most recent state stats, 38% of Black students in Sarasota County are reading at grade level, compared to 68% of White students.

“I just felt drawn to it,” Rini said of Newtown. “Super wealthy people already have school choice.” But all families deserve the ability to choose, Rini continued.

Every student at Star Lab uses a state choice scholarship and there are no other fees.

Rini could be a poster child for the wave of education entrepreneurs who are rising in Florida and other choice-rich states – both for the promise they represent, and the pitfalls they continue to face.

Due to fire-code complications, Star Lab could only serve five students this year. Rini didn’t learn about the snag until two weeks before school opened, and the remedy – a $97,000 sprinkler system – wasn’t financially possible. A local philanthropy recently stepped forward to help the housing authority pay for the sprinkler system. But Rini’s case isn’t an isolated one, as stories like this one and reports like this one highlight.

With the stars finally lined up at Star Lab, 14 students have already enrolled for this fall, and more are expected.

The draws are many.

For families who live in the complex, the school couldn’t be more convenient. The individual attention is tough to match. (Besides Rini, there’s another teacher and an assistant.) And it’s clear the school is enmeshed in the community.

Last month, the school hosted a “design lab” with local college professors and more than a dozen parents in the neighborhood, so the parents could discuss the educational needs of their children and how they could be better met. A few days later, Star Lab students built a float for the Newtown Easter Parade. In early May, the school hosted an international food festival for the neighborhood, so the students, their families, and their neighbors could, in Rini’s words, “travel the world through their taste buds.”

It’s not just families who are benefiting from the emergence of distinctive new schools like Star Lab.

“If you are not happy at your job, I would say don’t accept that as your fate,” Rini said, referring to other educators. “There are options, and some of them are already out there. And some of them don’t exist yet, but they might be in your head or in your heart.”

With choice, they don’t have to stay there.

Roots Academy in Sarasota lets students spend much of their time outdoors to learn amid nature while still offering a rigorous core academic program. Photo courtesy of Roots Academy

SARASOTA, Fla. – When Briana Santoro and her family moved to Florida in 2021, she set out to find the perfect school for her two young sons. She wanted a school that would be nature immersed, Montessori influenced, and academically rigorous. She found good ones that offered pieces of what she wanted, but none that put the whole puzzle together. So Santoro did what an accelerating movement of education entrepreneurs, including parents, are now doing all over Florida:

She created her own school.

“I just got to the point where I thought, ‘I’m going to solve my own problem,’” said Santoro, who has a background in business strategy consulting.

Roots Nature and Leadership Academy bills itself as “thoughtfully rooted in nature.” It serves 60 students in grades Pre-K through six, up from 25 when it opened two years ago. Nearly all of them use state-supported choice scholarships.

Santoro’s detailed vision includes fully engaged citizens.

As the second half of the school’s name suggests, creating future leaders is mission critical. There’s a big emphasis on problem solving, emotional intelligence, and entrepreneurship. From the earliest ages, the students literally get their hands dirty working on sophisticated science projects that touch on some of the most pressing environmental challenges.

First- and second graders recently learned how monoculture lawns and pesticides hurt pollinators, then created informational brochures and wildflower seed packets to hand out in their neighborhoods. Third- and fourth graders studied regenerative farming, then got a demonstration from scientists, via Zoom, on how soil samples can reveal the chemical differences between organic and inorganic approaches. Fifth- and sixth graders, meanwhile, learned how to make a vermiculture composter from a University of Florida extension agent, then shared their knowledge in a presentation to a community group.

“They’re learning skills that are going to be incredibly useful in how they live their lives,” Santoro said. “Appreciation for nature is going to set this generation up to solve the problems we’ve created.”

Roots rents space from a church. It has multi-age classrooms devoted to music, yoga, and projects. But clearly, its heart isn’t inside.

Santoro was inspired by Richard Louv’s “Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder.” She wanted to ensure her school honored children and “the essence of their childhood.”

To that end, the students spend 70 percent of their time outdoors, either on a whimsical campus where poodle chickens strut and peck under oaks and pines and a dozen varieties of fruit trees, or in an adjacent pine forest where they build forts, track animals, and otherwise range free for hours at a pop.

This is going to sound too good to be true, but bald eagles built a nest nearby and are frequently visible to students going about their day.

“The school is magical,” said Sarah Love, whose sons Harper, 9, and Carey, 12, attend Roots. “Children are laughing while butterflies are flying, and eagles are soaring overhead. I see kids learning academics while they’re on a mat on the ground with the sun shining on them. It just fills my heart.”

The school’s nature-inspired learning opportunities don’t end there.

Roots includes a “hen hotel” the students maintain themselves; learning “barns” full of Montessori materials the students use outside; and plans for a “special skills area” that will include everything from pottery and woodworking equipment to an outdoor fire cooking kitchen.

Gardening and archery are part of the curriculum. So are deep lessons about “gut health.” Beekeeping is on the horizon.

“They’re going to be better citizens if they know how to grow their own food, if they know how to care for the planet,” Santoro said.

Roots is as good an example as any to highlight one of the most underappreciated story lines to emerge as education choice has become the new normal in Florida:

Choice offers something for everyone.

This year, more than 500,000 students are using choice scholarships in Florida. As more and more parents signal their preferences for learning options, and more schools and other education providers emerge to serve them, more families and educators alike are realizing they can have exactly what they want. The evolving education landscape is increasingly dynamic and diverse.

By 2026, Roots expects to serve 75 students in Pre-K through eighth grade. In the meantime, it has 30 students on a wait list.

“Education is changing drastically,” Santoro said. “There’s a freedom of expression in education that’s never been there before.”

Santoro grew up in Canada. After a successful stint in business consulting, she went back to school to study nutrition. She became a certified nutritional practitioner, wrote a best-selling cookbook, and co-founded a company that specialized in high-end food supplements for kids.

With Roots, she wanted not only a top-notch program, but one that could be accessible to families regardless of income and could pay teachers well so she could attract the best.

With Roots, she wanted not only a top-notch program, but one that could be accessible to families regardless of income and could pay teachers well so she could attract the best.

The Roots staff is eclectic, talented, and all in on the mission. Several formerly taught in public schools.

On the school’s website, one of the teachers quotes famed environmental writer Rachel Carson. Another notes she was raised in a family of environmental activists who traveled the world with iconic oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. Yet another embraced organic farming and permaculture while living in Thailand.

“I was looking at, who is going to be breathing life into my children?” Santoro said. “If children don’t have a deep compassion for the earth … it’s just not sustainable. What better way to teach that than to live it every day?”

Parent Corbyn Grieco said there is a lot more going on at Roots than green vibes.

Her daughter is climbing trees, building pollinator gardens, and making homemade elderberry syrup. But the school also focuses on core academic standards, Grieco said, and constantly communicating with parents about how their kids are faring with them. Her daughter is reading several grades above grade level and digesting serious knowledge about health, science, and business development.

That’s the sweet spot, Grieco said: Roots is able to achieve academic success while honoring the magic of childhood.

“To this day,” she said, Roots “is the greatest choice we’ve ever made.”

A generation ago, Florida’s school districts could safely assume that most students would board a yellow bus (or perhaps walk less than two miles) to a public school they operated.

A few wealthy students might head to a private school. A handful of students from each neighborhood might board a different yellow bus to a local magnet or charter school. But these were marginal deviations from the norm.

A few wealthy students might head to a private school. A handful of students from each neighborhood might board a different yellow bus to a local magnet or charter school. But these were marginal deviations from the norm.

Now, those deviations are the norm.

Close to half a million Sunshine State students use a scholarship program to access a learning option of their choice. More than 400,000 students attend charter schools that aren’t operated by districts. All told, roughly half the state’s 3.4 million K-12 students attend a learning option other than their zoned public school.

There are unsung heroes in this story of expanding options: Florida’s 67 school districts.

With all the growth of charters and scholarship programs, district-operated options, — including open enrollment, magnet schools, career academies, and more — still account for the single-largest swath of school choice in the state.

Thanks to all these options growing at the same time, no school can take a student’s enrollment for granted. Every school has to earn the trust of every student or family who walks through their doors.

A survey by the national advocacy group 50CAN found 76% of Florida parents feel they have a choice in where they’re child goes to school.

That means that while half of Florida’s students attend a “school of choice,” half the remainder attend a local public school by choice, having considered other available options.

I’ve now experienced this change firsthand. I’m in the process of finding the right Pre-K for my daughter. After searching for miles and visiting private, charter, and district public schools, my wife and I landed on a clear favorite: Goldsboro Elementary, a magnet school operated by Seminole County Public Schools.

My daughter was enchanted by the astronomy lab. And of all the schools we spoke to, Goldsboro’s teachers had the clearest plan for ensuring our daughter, who currently reads on a first-grade level, will continue to be challenged academically.

Districts are stepping up their game. Competition from other options is certainly a factor.

But in recent months, I’ve had the chance to talk to district leaders across the state who are exploring a new frontier of educational options: They are looking for ways to offer individual courses and services to students using K-12 education choice scholarships.

These aren’t the stodgy bureaucrats that advocates and reformers sometimes cast as their foils in battles over the future of education. These are problem-solvers who hear the demand for new and different learning opportunities from their communities. They are working to respond.

In a future where every Florida student has access to abundant education opportunities, districts will play an essential role.

In its third era, public education aspires to expand equal opportunity by helping families and educators provide every student with an effective and efficient customized education through an effective and efficient public education market. We cannot achieve this aspiration without successfully implementing education savings accounts (ESAs).

ESAs are publicly funded flexible spending accounts that enable families to purchase the educational products and services they need to provide their child with a customized education. While ESAs are necessary to meet the unique educational needs of each student, we are still in the early stages of understanding how to best regulate and implement them.

Successful ESA implementations enable families to make purchases without unnecessary transactional friction. In this context, transactional friction refers to obstacles, complexities, conflicts, and inefficiencies that frustrate families and educational providers when they try to execute simple business transactions. These tensions come, in part, from needing to assure the public that every purchase is appropriate while not undermining customization by unduly limiting what families can purchase and/or overwhelming them with excessive bureaucracy.

Determining eligible ESA purchases

Determining the eligibility of families’ ESA purchases is a primary source of friction between families, providers, and ESA administrators. This school year in Florida over 500,000 families will spend about $3 billion making up to 2 million educational purchases for their students. Florida’s ESA administrators are responsible for ensuring each purchase is appropriate. Appropriate meaning consistent with state law and the unique needs of the student for whom a purchase is intended.

Determining if a purchase is appropriate for a specific student can be time consuming, which is problematic when an ESA administrator is reviewing millions of purchases annually. Families usually disagree when a purchase is denied and often initiate appeals through administrative, political, and media channels that can be time consuming and expensive to resolve. In Arizona, families are entitled to a formal administrative hearing when appealing a denied purchase. Often these hearings cost taxpayers more than the denied purchase.

When President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975, school districts, schools, and classroom teachers were required to work with families to create customized learning plans called Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) for special needs students. This was the first instance of government requiring public education to provide students with a customized education, and the results have been mixed. For many families, the IEP process works well. Others feel schools and school districts erroneously deny students needed services, leading to contentious appeals that sometimes result in litigation.

Despite these tensions in the IEP process, I suspect most ESA administrators will eventually use certified educators and accredited public and private educational institutions, with the assistance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), to help determine which ESA purchases are appropriate for each student. This approach should be less contentious than the IEP process since ESA families must use their students’ ESA funds, and not school district resources, to pay for services. This includes any services their students receive from school district staff.

Reimbursements and transactional friction

In some ESA states, families may purchase pre-approved educational products and services through an e-commerce site or use their personal funds and submit receipts to their state’s ESA administrator to get reimbursed. Reimbursements provide families with access to products and services not included on their state’s e-commerce site and allow for timely purchases. If a student needs materials to finish a science project that is due tomorrow, the family can make an out-of-pocket purchase and hope to get reimbursed.

While reimbursements provide families with purchasing flexibility, they come with complexities that generate transactional friction. Families must submit receipts showing each purchased item and its cost. These receipts are sometimes blurry and difficult to read, or the item descriptions are too vague for ESA administrators to determine whether they are eligible, requiring families to spend time getting new receipts.

Determining a service provider’s eligibility to receive ESA funds also often complicates reimbursements. A family may think a speech therapist is eligible to be compensated by ESA funds, but when they submit a receipt, the ESA administrator has no record of the therapist’s license. This causes delays while the therapist submits her current state license to the ESA administrator to establish or reestablish eligibility. Many families cannot afford waiting several weeks to get reimbursed or pay the additional credit card interest caused by these delays.

To reduce and eventually eliminate reimbursements, some ESA administrators are exploring creating standardized commodity codes that will enable families to buy pre-approved educational products and services using debit cards. This solution, which will probably take a few years to fully implement nationally, will be like Health Savings Account (HSA) cards. If enough states join this effort their collective market size should be sufficient to convince most vendors to participate.

In the interim some states are using or preparing to use technology such as Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to automate reimbursement processing. This automation will expedite the processing of reimbursements that do not require an educator to determine if a purchase is appropriate for a specific student.

Arizona is using risk-based auditing to accelerate its reimbursement processing. This involves automatically approving all ESA purchases under $2,000 and then auditing those purchases that have a significant probability of being ineligible. If an audit determines a purchase is ineligible the family must repay their ESA account. And in Florida, Step Up For Students is making excellent progress processing reimbursements more effectively and efficiently using technology and better workflow processes.

These interim solutions are an important bridge to a future in which debit cards and statewide networks of certified educators and accredited educational institutions enable public education to provide an effective and efficient customized education to millions of students with little unnecessary transactional friction.

Some transactional friction will always exist in public education, and it should. How well we manage this friction will help determine how successful we are.

This school year, Florida is empowering half a million students to direct funding to education options of their family’s choice.

In the 2023-24 school year, after Gov. Ron DeSantis signed HB 1, Florida saw the largest single-year expansion of education choice scholarships in U.S. history. That growth continued in 2024-25.

Florida’s education choice scholarship programs have grown steadily over the past decade. *Numbers for the 2024-25 school years are preliminary. In 2022, the McKay Scholarship and Unique abilities programs merged.

The numbers look like this:

With more than 500,000 K-12 students participating in some type of full-time education savings account, Florida is home to nearly 7 of every 10 students using such programs nationwide.

If the students using these programs in Florida counted as a school district, it would be the largest in the state and third-largest in the country, trailing only New York and Los Angeles.

Add it all up, and half a million Florida students will direct funding from a state-supported program to access a learning option of their family’s choice. This is a milestone 25 years in the making.

As the movement for education options gains momentum across the country, there remains a clear national leader: Florida.

This school year, the Sunshine State’s education savings account programs are larger than their counterparts in every other state put together. Including programs that provide flexible funding to public-school students, they are on track to serve more than 500,000 students this year.

To put the scale of these options in perspective, if students in Florida’s scholarship programs counted as a school district, it would be the third largest in the country, after New York City and Los Angeles.

But this is not simply a story about scale or numbers. ESAs allow families to direct education funding to eligible learning options of their choice. The ability to personalize a child's education empowers families in profound ways.

Meet five families who have taken control of their children’s educational destiny.

Caleb Prewitt

Caleb has been riding horses since he was 4 years old. Caleb is now 17 years old and has participated in 36 triathlons. He recently raced the international distance, which is an 800-meter swim, 16-mile bike, and 10k run. He was the youngest competitor (all divisions) for the International.

Caleb has been riding horses since he was 4 years old. Caleb is now 17 years old and has participated in 36 triathlons. He recently raced the international distance, which is an 800-meter swim, 16-mile bike, and 10k run. He was the youngest competitor (all divisions) for the International.

“We have set out from early on not to put limits on him; to keep our expectations high,” his mom, Karen, told me. “With opportunities and support, so much is possible for people with disabilities. So much more than is expected.”

Caleb is a well-known figure in his community and on social media, where he shares uplifting news, spreads joy and offers cooking lessons to his followers. Caleb’s love for the culinary arts shines through as he bakes cookies for Happy Brew, a local coffee shop that employs individuals with unique abilities.

Caleb loves going to school, says Karen. He attends North Florida School of Special Education in Jacksonville. She notes that the scholarship not only brightens Caleb’s life but also brings joy to their family, as it has created many opportunities and opened doors for them. “For several years, Caleb has benefitted from the FES-UA scholarship, which has provided him with a supportive learning environment and numerous unique opportunities,” Karen said. “We are deeply grateful for the positive impact it has had.”

Viktoriia Galushchak

The Galushchak family immigrated to the United States from Ukraine three years ago to escape the war. The family was in a new country, speaking a different language with no car and little money. But at age 11, Viktoriia really wanted to go to school to make some friends. “We are so grateful for Step Up because it allowed us to put our children into private school,” her mother, Olga Galushchak, explained.

The family found St. Paul Catholic School that was a 10-minute walk from their house, and Viktoriia enrolled in the spring of 2022. Olga says it was such a blessing. Viktoriia’s English was strong from studying it in Ukraine, so her transition to school went well. At home, the family speaks only English one day a week to strengthen their skills.

Viktoriia entered the school science fair in seventh grade. Her project: creating a computer program to help deaf and mute people. She was inspired by an experience with car trouble during their journey to America. They received help from two men who were deaf and mute, and Viktoriia was determined to find ways to help people like them communicate more effectively. The project won third place in the state science fair in 2023.

Viktoriia set her sights on first place for the eighth-grade science fair. She created a program to help children learn foreign languages that would give them real-life examples while they used it. This project won first place in the state science fair, and she received a grant award for the project. Viktoriia and her family are eagerly waiting to learn if she will be selected to present her project at the national science fair in Washington, D.C.

Viktoriia is now a freshman at a Bishop Kenny High School in Jacksonville, still using the Florida Tax Credit scholarship to help pay tuition. The family is grateful for the scholarship, and they do not think Viktoriia’s last three years would have been the same if she did not have the opportunity to attend a school that fit her needs so well.

Kingston, Zecheriah and Gabriel Lynch III

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Lynch family had to quickly adapt, and they chose to transition from a private school to homeschooling.

Even after the pandemic ended, the family continued homeschooling. In 2023, their three children received the newly established Personalized Education Program (PEP) scholarship, which they say has been instrumental in their journey.

The scholarship provided invaluable resources, including one-on-one tutoring. This personalized support made a profound difference in Kingston, who struggled in math but began to make significant strides. Mom said the scholarship allowed him to receive tutoring with a certified math teacher, who can pinpoint his needs and ensure he understands the material before moving on.

The Lynch family’s homeschool setup now includes daily tutoring, vocal lessons, and a range of educational resources, transforming their learning environment into one that nurtures each child's growth. Parents Krystle and Gabe Jr., who is a district school PE teacher, have successfully balanced their professional and family responsibilities while supporting their children's education. Their Jamaican and Panamanian heritages have added depth to their homeschool experience: the boys are taking Spanish this year. Both parents are very committed to a strong education and work ethic, so they try to incorporate these values in their schooling. Reflecting on the impact, Krystle says, "I am so excited for the families that will receive the PEP scholarship this year. [It’s] an amazing program that caters to students individually. Such a blessing."

Sebastian and Alejandro Broche

Aimée Uriarte, a dedicated single mother from Costa Rica, made a pivotal decision four years ago to move to the United States, driven by her commitment to providing her sons with a strong educational environment that would offer exceptional opportunities.

Her eldest son, Sebastian, now 18, graduated with honors from Christopher Columbus High School in Miami which he attended thanks to the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options (FES-EO). As president of the school's student-run broadcast news program, Sebastian led a team that won numerous national accolades. In fact, the brothers have combined to win more than 60 awards for directing and graphics. Sebastian earned a $4,500 per semester scholarship from the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, received a $7,500 grant from Media for Minorities, and received the Mike Wallace Memorial Scholarship, worth $10,000, funded by CBS News.

Alejandro, who recently turned 16, has attention deficit disorder, which qualified him for the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities (FES-UA). The previous school he attended during the pandemic wasn't meeting his needs, but Aimee was confident that the Catholic high school was the right environment for her son to reach his full potential. Her belief was confirmed when Alejandro, as a freshman, won a Student Television Network national award in Long Beach, California, following in his brother's footsteps. A year later, he took first place for a nationwide commercial and won several Student Emmys, including one for best graphics in the recognized documentary "Live Like Bella."

Aimée credits these remarkable accomplishments and transformative opportunities available to her sons to the vital support of the scholarships. “I think every family deserves the scholarships, regardless of income or their child’s conditions,” said Aimée, who added, “I think the whole country should emulate Florida.”

Vanessa Giordano

Vanessa is a thriving 16-year-old in 10th grade. However, her early years as a premature twin were not so easy. She struggled to meet developmental milestones and was diagnosed with dyslexia. Her mom, Alicia, worked hard to advocate for education options in Texas. In 2023, their family moved to Florida and were delighted to learn the state offered a scholarship program for children with unique abilities.

Vanessa is a thriving 16-year-old in 10th grade. However, her early years as a premature twin were not so easy. She struggled to meet developmental milestones and was diagnosed with dyslexia. Her mom, Alicia, worked hard to advocate for education options in Texas. In 2023, their family moved to Florida and were delighted to learn the state offered a scholarship program for children with unique abilities.

Fast forward. Vanessa is now in her second year at Bishop McLaughlin High School in the Tampa Bay area and using the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Unique Abilities. Her teachers have encouraged her to explore her talents and try new things. She is an active member of the worship team and enjoys singing at school events. She had her first role in a school play as “Chip” from “Beauty and the Beast.” She is also a sideline cheerleader and part of the competitive cheer team. Despite her robust extracurricular schedule, Vanessa always maintains grades that keep her on the honor roll.

“I am so grateful for Step Up for Students for helping my daughter,” Alicia Giordano says. "Every child can soar if given the opportunity to be in the right school for them and Step Up for Students makes this dream possible.”