If 2021 is to be different from 2020 for families of school-aged children, policymakers, parents and educators must have a conversation about bullying – not from fourth graders on the playground, but from the education special interest groups that are pushing parents around.

If 2021 is to be different from 2020 for families of school-aged children, policymakers, parents and educators must have a conversation about bullying – not from fourth graders on the playground, but from the education special interest groups that are pushing parents around.

Examples abound in West Virginia, where families and community leaders celebrated National School Choice Week last year by doing the same thing they have been attempting for months: trying to create a public charter school in one of the last states in the nation without one.

In 2019, West Virginia lawmakers removed their state from the dwindling list of states that do not allow for the creation of public charter schools, leaving only five with this ignominious distinction.

Katie Switzer grew up attending traditional schools and intended to send her children to the same, but she already was aware of the possibility that assigned schools may not be a fit. Katie’s husband, whom doctors diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum, had been picked on incessantly in school.

Katie was encouraged about the potential for public charter schools in West Virginia and the new learning opportunities available to them if their children faced struggles similar to those her husband encountered.

But Katie says she was “taken aback” last October when she attended an informational hearing on the lone charter school application. There was a “massive teacher union rally” at the event, and the union members took nearly all of the 50 allotted slots for members of the public who wanted to make comments.

“It was, frankly, bullying that happened at the public information session,” Katie says. “Hardly any of them talk about the kids and how it would affect the children.”

“I want my kids to be exposed to a place where people act like adults and don’t shut people down because they have different opinions,” she continues.

Katie’s experience with these union tactics isn’t unique, unfortunately. Despite sagging student grades and an estimated 3 million “at-risk” students who have not had any formal education during the pandemic, parents around the U.S. watched teacher unions hold protests in 2020 to keep schools closed to in-person learning. Unions still demand new taxpayer spending on schools on top of the billions in new federal spending Washington already approved last year.

Most families who are not ready to send their children back to brick-and-mortar schools will have virtual options available to them in the assigned system for the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, teacher unions have consistently opposed and even tried to block schools from offering in-person instruction as a choice for parents who are ready for their children to go back to class.

Recently, Chicago’s teachers union—which, ironically, has a site dedicated to dealing with workplace bullying by administrators—called on members to refuse to go back to work at all.

This puts these special interest groups at odds with student needs and what some parents have decided is best for their children. A new survey finds that parents of 51% of students who “attend school as usual say they are ‘very satisfied’” with their child’s experience at this point in the pandemic, while parents of just 23% of students who are only attending school virtually said the same. Sixty percent of respondents said their child is learning less overall this year.

According to forthcoming Heritage Foundation research, public school enrollment numbers were lower at the beginning of the 2020-21 school year than in the year prior, and we should anticipate more student attendance changes before the end of the school year. Enrollment is down in New York City, Montana, Wisconsin, Missouri, North Carolina and elsewhere, while homeschooling and charter school figures were up at the beginning of the school year.

With this year’s National School Choice Week in hindsight, we should continue to celebrate the opportunities children have to succeed in school and in life when their parents can choose where and how students learn.

At the same time, we should ask officials in places without alternatives to assigned schools why 3 million students from disadvantaged backgrounds have simply disappeared.

While you have their attention, note that this disappearance coincided with union intimidation tactics aimed at parents and local officials.

As COVID-19 divides communities according to those with or without access to solutions for work, health and education, policymakers ought to give families more educational options—like charter schools and education savings accounts—that can help parents and communities more effectively handle the challenges of this time while keeping the bullies of public school policy at bay.

A bill that would allow parents to hold their children back a grade to make up for COVID-slide learning losses sailed through the Senate Education Committee on Wednesday.

A bill that would allow parents to hold their children back a grade to make up for COVID-slide learning losses sailed through the Senate Education Committee on Wednesday.

S.B. 200, filed by state Sen. Lori Berman, D-Boynton Beach, would let parents of children in kindergarten through eighth grade make the decision to have the child repeat a grade only during the 2021-22 school year. Current law allows district school principals to make retention decisions. The law prompted one parent to pay out of pocket for her son to a private kindergarten so that she and her husband could decide whether he was ready for first grade.

The bill follows through on an announcement that Gov. Ron DeSantis made last spring that parents would be allowed to hold their children back a grade in the fall if they had concerns about learning losses from online instruction.

DeSantis did not formalize his intentions with an executive order, and later guidance from Florida Department of Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran recognized that while parents have a right to provide input, the final decision regarding student retention rests with school officials.

Berman filed her bill in response to parents’ concerns over the learning losses that occurred in March after the pandemic shuttered school campuses. Though all Florida district schools were required to open in August for full-time, in-person instruction, some families enrolled their children in online options that the districts could offer under an executive order from the DOE.

“We know that the COVID slide is real and troubling,” Berman told education committee members during the meeting. She cited data from Palm Beach County that showed the percentage of middle school F’s increased from 1.6 to 7.7% this past year.

Under the bill, parents with children enrolled in elementary and middle schools would have until June 30 to request from their district superintendent that their child repeat a grade next year. Superintendents would be required to approve all timely petitions and would have discretion over requests that are filed late.

Berman said she agreed to narrow the scope of the bill to exclude high schoolers ahead of Wednesday’s meeting after speaking with Corcoran, who expressed concerns about its effect on older students and athletes.

“One of the reasons why we amended the bill overall down to K-8 was so that we would not run into a lot of the issues that happened in high school with eligibility and things like parents wanting their child to attend prom,” Berman said in response to questions from Sen. Travis Hutson, R-St. Augustine, who asked if the bill could include provisions for retained students who were deemed ineligible to participate in activities as a result of their parents’ decision in 2021 to hold them back a year. Berman said she was open to considering it.

The bill cleared the committee by a 9-0 vote. Sen. Doug Broxson, R-Gulf Breeze, did not vote on the proposal.

The bill has two more committee hearings in the Senate. A companion bill is expected to be filed soon in the House by state Rep. Kelly Skidmore, D-Boca Raton.

In an early episode of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” our protagonist wanted to go on a date rather than investigate a diabolical menace. “If the apocalypse comes, beep me,” she tells Giles, her overseer.

In an early episode of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” our protagonist wanted to go on a date rather than investigate a diabolical menace. “If the apocalypse comes, beep me,” she tells Giles, her overseer.

An apocalypse did indeed come in 2020, but fortunately, only in the initial meaning of the word.

The Greek word apocalypse means to uncover, reveal, lay bare, or to disclose. The year 2020 was apocalyptic not in the biblical or the later Buffy/zombie/robot sense, but rather in the original meaning. Unfortunately, much of what 2020 revealed has been unfavorable.

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, I read an article that matter-of-factly described the United States as a country with “poor quality public services.” I stared long and hard at that sentence, trying to decide whether it was a fair assessment.

In the end, it was a conclusion which I found impossible to deny.

It’s difficult to say just when in 2020 this was laid bare. Was it when the agency that receives multiple billions of dollars to prepare for a pandemic released flawed COVID-19 tests?

Maybe it was later, when I listened in horror to the tale of how the Food and Drug Administration had hamstrung the use of salvia tests during the opening stanzas of the pandemic. These tests were more accurate, didn’t require either a swab (which were in short supply) or anyone tickling your outer brain through your nose.

Not to worry. The FDA kept you entirely safe from these tests during exactly the period when we needed them most. Unfortunately, COVID-19 spread like wildfire during the CDC-FDA testing fiasco.

On the other hand, the moment of revelation might have been the unique confusion displayed by American public health officials about the efficacy of masks in slowing the spread of a **cough** upper respiratory disease. Nothing like watching our technocratic grandees debate over something obvious to anyone with even the faintest lick of sense.

As you may recall, we were first advised that masks could spread the disease before we were told that they were indispensable to slowing the spread of the disease.

Let’s just pretend I spent a few additional paragraphs discussing that while American scientists created one of the vaccines (finally!) in use in two days, it took American public health authorities approximately 150 times as long to give us permission to use said vaccine.

By the way, this is “warp speed” for our glacial authorities. Millions of people around the world might have died and the global economy could have faced certain ruin if something went wrong with a vaccine after all.

Oh, wait. That’s actually what happened.

Not to be outdone by our public health officials, America’s education system has decided to give them a run for their money. While school systems around the world and within the United States not only have managed to safely reopen, some never closed in the first place. Now comes word that despite being prioritized for vaccines, some teacher unions are expressing skepticism about reopening nine months from now.

(Click here for a visual “huh?”)

What has been uncovered, revealed, laid bare and/or disclosed in the COVID-19 apocalypse? If you said, “the need for American self-reliance,” give yourself a gold star. The less reliant you are on dysfunctional authorities to take care of yourself, your family and your community, the better.

You can try to beep the Slayer, but you would be better served by sharpening a stake of your own.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwallbach, research associate and project coordinator at The Heritage Foundation, originally appeared in The Daily Signal.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwallbach, research associate and project coordinator at The Heritage Foundation, originally appeared in The Daily Signal.

National School Choice Week has taken on renewed importance this year, as too many families are approaching the one-year mark of crisis online learning provided by their public school district.

National School Choice Week has taken on renewed importance this year, as too many families are approaching the one-year mark of crisis online learning provided by their public school district.

Last March, the coronavirus pandemic shuttered schools nationwide, forcing teachers, parents, and students to transition to virtual classrooms and grapple with the various effects of lockdowns. Ten months later, parents report that 53% of K-12 students are still learning in their virtual classrooms.

Public schools have remained largely closed to in-person instruction.

Recent research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that in-person learning is rarely a source of large outbreak. Even though in-person learning is one of the safest activities for children, proposals to reopen district schools for face-to-face learning have met with staunch opposition from teachers’ unions.

Inexplicably, teachers unions have also rejected measures which would require teachers to be more available to students throughout the day via live video.

The Center on Reinventing Public Education’s director, Robin Lake, told the New York Times that the teachers unions’ vacillating responses feel “like we are treating kids as pawns in this game.”

Adding to parents’ frustrations, teachers unions have also taken the opportunity to push for a whole host of concessions that have nothing to do with health safety.

For instance, the American Federation of Teachers has a long list of demands, including: additional food programs, guidance counselors, smaller classes, tutors to assist teachers, and “culturally responsive practices.”

Similarly, The United Teachers of Los Angeles has demanded a moratorium on charter schools, higher taxes for the wealthy, and “Medicare for All.”

The blatant, non-pandemic-related demands of many teachers unions have illustrated what Stanford University professor Terry Moe noted a decade ago: “This is a school system organized for the benefit of the people who work in it, not for the kids they are expected to teach.”

The inflexibility of teachers unions has increasingly become a source of escalating tension with local officials. For example, Chicago Public Schools, the third largest school district in the nation, locked teachers out of their virtual classrooms after they refused to return to in-person instruction with classrooms at less than 20% capacity.

Such unbending posture has provoked the ire of parents and left many children frustrated, both academically and socially. As Tim Carne wrote in the Washington Examiner, “The very people who have most loudly declared the importance of public schools now are deliberately destroying public schools.”

Many parents are tired of being strong-armed by teachers unions and have pursued alternative education options for their children.

For instance, the learning pod phenomenon, wherein parents work together to pool resources and hire their own tutors and materials is popular. This allows students to return to in-person lessons, even if school districts refuse to reopen.

Last September, a national poll by the pro-school choice nonprofit EdChoice indicated that 18% of surveyed parents were looking to join one. At the same time, 70% of surveyed teachers reported interest in teaching in a pod.

A recent report by education scholars Michael B. Henderson, Paul Peterson, and Martin West found that approximately 3 million students—nearly 6% of K-12 students—currently participate in a learning pod.

Notably, pod participants are more likely to be “from families in the bottom quartile of the income distribution.” The authors wrote, “Parent reports suggest that 9% of all students from low-income families and 5% of all students from high-income families are participating in pods.”

Families have embraced private school options, too. A survey last November of 160 schools in 15 states and Washington, D.C., showed that half of the surveyed private schools experienced higher enrollment this academic year than they had the previous year pre-pandemic.

Moreover, more than 75% of surveyed private schools were open for in-person instruction. The remaining schools offered hybrid education, which is a combination of in-person and virtual learning.

Children could have greater access to private education if more states made education dollars student-centered. For instance, parent controlled education savings accounts allow parents to spend their funds on approved education costs, like private tutoring, books, or tuition. These accounts already exist in five states.

National School Choice Week is an important reminder that “public education” means education available to the public, regardless of the type of school it takes place in. It is the perfect time to remember that parents, not teachers unions, are best positioned to determine the education needs of children.

School choice options like education savings accounts can bring education consistency to families across the country during a most uncertain time. National School Choice Week is an important reminder of that.

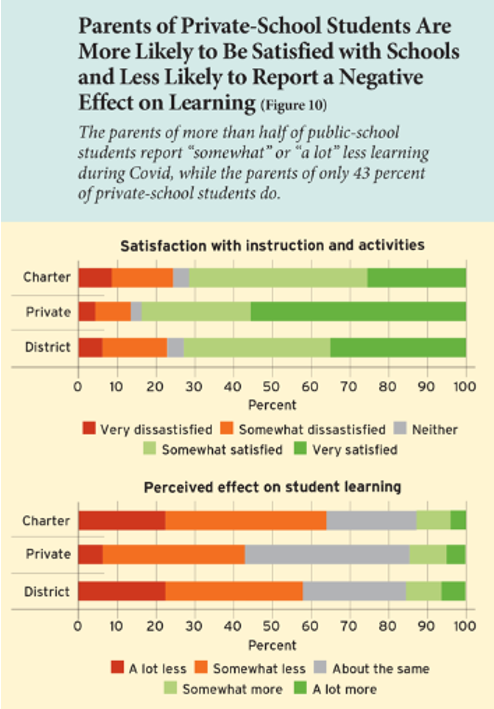

Nearly a year after the COVID-19 pandemic began and reshaped the nation’s education system, parents of private and charter school students are more likely to be satisfied with their schools and less likely to report a negative effect on learning than their public school counterparts. That’s a key finding in the latest survey from Education Next.

Nearly a year after the COVID-19 pandemic began and reshaped the nation’s education system, parents of private and charter school students are more likely to be satisfied with their schools and less likely to report a negative effect on learning than their public school counterparts. That’s a key finding in the latest survey from Education Next.

The survey was conducted by Michael B. Henderson of the University of Louisiana, and Martin West and Paul E. Peterson, both of Harvard University. The researchers surveyed 2,155 American parents with children in grades K-12 in December, examining parental satisfaction as well as the impacts of remote and hybrid learning on students since the pandemic started.

As with the last survey in September, parents expressed general satisfaction even as their children are learning less. Private school students continue to be more likely to receive in-person instruction, where parents are more likely to report lower levels of learning loss and lower negative impacts on the student’s social, emotional and physical well-being. Overall, parents are generally satisfied with schools (71% district, 73% charter and 83% private). Private school parents are more likely to be very satisfied – 55% – compared to 35% for charter parents and 25% of district parents.

Just 18% of private school parents reported their children were learning remotely, compared to more than half for district and charter school students.

Despite this broad satisfaction across sectors, 60% believe their children are learning less than they did before. In-person learning was closely related to higher reported satisfaction and lower reported learning losses.

A small difference exists between sectors regarding impacts on “student’s academic knowledge,” with 38% of district parents reporting negative impacts to 30% of private school parents. A similar 8-point difference was observed for parents reporting negative effects on their child’s emotional well-being.

Parents do report significantly higher negative impacts on their child’s social relationships and physical fitness at district and charter schools compared to private ones.

Private schools offering remote learning do lag behind their counterparts for teachers meeting with the entire class, but there’s little difference on one-on-one teacher student meetings. Remote private schools also lag behind on weekly homework assignments (84% of parents report weekly assignments) compared to district schools (93% of parents report weekly assignments).

The survey also makes several interesting observations.

While district enrollment fell 9 percentage points between the Spring and Fall of 2020, researchers found it had little to do with the school districts’ response to the Covid pandemic.

Just 10% of new private school students and 14% of new charter school students switched due to dissatisfaction with their prior school’s response to Covid. However, among new home school parents, 61% were dissatisfied with their prior school’s response to Covid.

Meanwhile, 32% of private school parents and 19% of charter parents were dissatisfied with their prior school in some way. Parents were more likely to switch schools because of moving or because their prior school no longer offered the child’s grade level.

Covid safety appears to be roughly similar across sectors. While private school students are far more likely to attend school in person, parents across all sectors report incidents of Covid infections at roughly the same rate. Parents also equally report their school sector is doing “about the right amount,” when it comes to Covid safety measures.

Another discovery was the rate at which parents utilized in-person learning when compared to local Covid infection rates. Counties in highest quartile of infection rates offered more in-person learning options than counties with the lowest options.

Despite noting this “perverse result,” researchers also state that the observed result does “not constitute evidence that greater use of in-person learning contributed to the spread of the virus across the United States.”

Despite children learning less, parents are generally satisfied across all school sectors.

This commentary from redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher, senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, and center director Lindsey Burke, first appeared on Tribune News Service.

This commentary from redefinED guest blogger Jonathan Butcher, senior policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy, and center director Lindsey Burke, first appeared on Tribune News Service.

When it comes to her daughter Emerson’s education, Sarrin Warfield says, she’s “in it to win it.”

When Emerson’s assigned school in South Carolina announced plans for virtual learning this fall, Sarrin says she asked herself, “What if we just made this in my backyard and made a school?” After talking with friends who have children the same age as Emerson, Sarrin said, “Let’s do it. Instead of it being a crazy idea, let’s own this process and be really intentional about doing this and make it happen.”

Sarrin is one of the thousands of parents around the country who formed learning pods when assigned schools closed. By meeting in small groups with friends’ and neighbors’ children, these pod families could try to keep at least one of part of their child’s life from being upended because of COVID-19.

The time-honored practice of school assignment did little to help the Warfields — or thousands of other students around the U.S. during the COVID spring … and then COVID summer and fall. In the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year, officials in some of the largest districts in the country reported significant enrollment changes from the previous school year, especially among younger students.

Officials in Mesa, Arizona, reported a 17% decrease in kindergarten enrollment after the first two weeks. In Los Angeles, Superintendent Austin Beutner reported a 3.4% decrease in enrollment, but said another 4% of students couldn’t be found, making the change closer to 7%. Figures are similar in Broward County, Florida, and Houston. In large school districts, these percentages amount to over 10,000 children per district.

Some of these changes can be attributed to learning pods. But officials in large cities and even those representing entire states simply reported having no contact with many students.

Under normal circumstances, if thousands of children who were once in school suddenly were nowhere to be found, this would be an issue of national concern. Hearings would be held, and officials would demand to know what is happening with schools around the country. Loud calls for change would be heard.

But life during the pandemic is anything but normal.

Likewise, if more students around the country were failing — say, twice the figure from last year — this would also be worrisome, right? From Los Angeles to Houston to Chicago to Fairfax, Virginia, school officials and researchers are now reporting that the proportion of students earning D’s and F’s in the first semester has increased, doubling in some cases, in comparison to the last school year.

Yet across the U.S., many school districts, especially those in large metro areas, remain closed to in-person learning for some if not all grades and may not reopen at the start of 2021.

According to the Pew Research Center, 72% of parents in lower-income brackets report being “very” or “somewhat” concerned this fall that their children are “falling behind in school as a result of the disruptions caused by the pandemic.” With thousands of students not in class, even virtually, and falling grades among those who are attending, who can blame them?

For taxpayers and policymakers looking for lessons in the pandemic, the utter failure of school assignment systems to provide quality-learning options to all students, especially the most vulnerable, is clear.

The quality and consistency of the education a child received during the pandemic has been dependent on the attendance boundary in which that child’s family lives. At the same time, so many of the issues plaguing education during the pandemic — and for that matter, the entire century leading up to the pandemic — are rooted in policies that fund school systems, rather than individual students.

Allowing dollars to follow children directly to any public or private school of choice is a critical emergency policy reform that states should pursue. Such a policy change is overdue.

Since it’s anyone’s guess how soon life will get back to normal, we can’t wait any longer for the system to fix itself.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Adam Peshek, a senior fellow for education at the Charles Koch Institute, first appeared on Real Clear Education.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Adam Peshek, a senior fellow for education at the Charles Koch Institute, first appeared on Real Clear Education.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an unprecedented opportunity to rethink education in America. Instead of hoping for a return to “normal,” let’s learn from what has worked – and what has not – to make lasting improvements and create a more resilient system, one that can adapt to any challenge families may face in the future.

The first step toward realizing a more resilient and family-centered system is to reimagine how we fund education. In short, it’s time to start funding families, not the buildings that are meant to serve them.

Americans spend at least $720 billion on education each year. At around $13,000 per child, that puts the U.S. among the highest-spending countries in the world.

Instead of providing this benefit directly to families – as we do for higher education, childcare, and health care – in K-12, we send this money directly to school buildings. Taxpayer dollars are collected and sent to a central office, and zones are drawn around individual schools where students are required to attend or forfeit the funds raised for their education.

The pandemic has exposed the flaws in this system. School closures, loss of childcare, and difficulties transitioning to online and hybrid-learning models are having devastating effects on children. According to one report, an estimated 3 million students have received no formal education since schools closed in March. That’s the equivalent of every school-aged child in Florida failing to show up for school.

The economic impact on students is estimated at $110 billion in lost future earnings each year. Unsurprisingly, this decline in learning has been felt more deeply by children in low-income families.

These challenges might seem insurmountable, and many of us look forward to the day when we can return to “normal.” But why would we want to return to a status quo that has proven a failure during a time of crisis? While we may not encounter an international crisis of the scope and scale of COVID-19, families face immeasurable local and personal crises each year.

This is a time to learn from innovations that have proven successful and integrate them into the system moving forward.

One of the biggest innovations during the pandemic has been the proliferation of individualized education. Families with resources – financial and otherwise – are taking matters into their own hands. They are hiring tutors, forming learning pods, enrolling in microschools, sharing childcare, reimagining after-school programs, and rearranging their lives to provide the continued learning opportunities that many children have lacked for months.

These unconventional models may yield academic benefits. Researchers from Opportunity Insights analyzed data from 800,000 students enrolled in an online math curriculum used by schools before and during the pandemic. The researchers found that students in low-income neighborhoods saw a 9% decline in math progression between January and April. Meanwhile, students from wealthy ZIP codes saw a 40% improvement over the same period.

In other words: in the spring, with schools closed during the pandemic, students in some wealthy families may have progressed academically at higher rates than if the schools had remained open.

This is raising understandable equity concerns from advocates concerned about widening gaps between low- and high-income students. But in a situation where some students are progressing and others are falling behind, the solution isn’t to move everyone to the middle. It’s to give those falling behind access to the same type of learning that is allowing others to thrive.

The sort of family-directed, individualized education taking place during the pandemic is likely to expand its presence in American life. As an Atlantic article observed, “COVID-19 is a catalyst for families who were already skeptical of the traditional school system – and are now thinking about leaving it for good.”

The author of that piece, Emma Green, recently said in an interview that home-based, unconventional methods of education are getting “a flood of interest from parents of all kinds.” Early data seems to confirm this, with large upticks in families opting out of school systems to pursue homeschooling.

To create a more effective and more resilient education system, we must learn from what has proven effective during the pandemic – namely, the ability of those with resources to identify and pursue a variety of individualized learning opportunities to meet children’s needs. To provide these same opportunities for all families, governments should prioritize direct grants to families, education spending accounts, refundable tax credits, and myriad other ways to get money into the hands of families so they can build an education that fits their needs.

The way in which we currently fund education is blocking equal access to these learning opportunities. To expand that access, we need to fund families, not school buildings.