Earlier this week, reimaginED executive editor Matt Ladner wrote about the latest in a series of pandemic-related challenges for K-12 education: a severe shortage of school bus drivers, which is hampering the ability of schools to get children delivered to their classrooms.

Now, Chad Aldeman, policy director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, and Marguerite Roza, Edumonics Lab director and a research professor at Georgetown University, have weighed in on the dilemma for The 74.

Like Ladner, Aldeman and Roza acknowledge that innovation isn’t necessarily a strong suit for public school districts. The bus driver shortage is just another challenge that has school leaders scrambling. Their reactions to this particular challenge, Aldeman and Roza say, can be illuminating:

“How districts react to these unusual labor challenges may be telling us something important: whether they can adapt to meet the moment and which, if any, will consider adopting innovations that are common in other industries outside of education.”

Some districts have either delayed the start of their school year or suspended bus routes through October. Others are doing what they can to attract (or retain) bus drivers via higher pay and better benefits. But, the authors note, a number of districts are taking more innovative approaches, and some have begun completely rethinking their transportation processes.

Which seems like a much saner way to go than calling in National Guard members, the route Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker chose to take.

One of the more interesting ideas Aldeman and Roza unearthed came from Chicago school leaders, who are offering stipends of up to $1,000 upfront and $500 a month to parents willing to take on the responsibility of getting their children to class.

You can read more about that idea and other ways school districts are coping here.

Vinicus and Rafaela Reis of Boca Raton, Florida, are enrolled in Florida Virtual School, which allows them to attend classes from the family's dining room table.

“ … our children discovered a new way of learning that has worked well for them. They enjoy the classes, their teachers, and the flexibility of learning online.” – Marcela Reis

Marcela Reis is a mother of three from Boca Raton, Florida. All three children attend Florida Virtual School, the state’s public school district offering more than 190 courses to students in kindergarten through grade 12.

Her two daughters, Manuela, a sophomore, and Rafaela, a fifth grader, attend through the part-time Flex program, while her son, Vinicus, also known as Vini, is a seventh grader enrolled in the school’s full-time program. The family originally signed up for Florida Virtual School so they would have freedom to travel around the world, but they since have found it a haven from the pandemic and decided to stay for a second school year.

reimaginED interviewed Reis to learn more about how her children have adapted to virtual learning during the pandemic and how they’ve benefited from it. Answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q. What did your children’s education look like leading up to your decision to attend FLVS?

A. Before attending FLVS, my oldest daughter went to private school and my other two children attended their district school, Verde Elementary. They loved the schools they went to, and they had great experiences. They were also very active, participating in science clubs, theater, cheerleading, and other activities.

Q. What factored into your decision to enroll at FLVS?

A. We originally were researching FLVS because my husband and I were looking for a flexible online education option that allowed our children to do their schoolwork from anywhere and at any time so that we could take a one-year sabbatical and travel the world together. But then when the pandemic hit, our travel plans came to an abrupt halt. Even though we were disappointed and worried about the state of the world, we were thankful that we already had plans to dive into online learning so that our children could continue to learn and stay healthy in a safe environment.

Q. How did you adjust to virtual education? What were the biggest challenges? What were the biggest benefits and rewards?

A. My children adjusted relatively quickly to an online learning environment, with all three of them constantly telling me how much they enjoyed their schoolwork and their teachers. Something that I was nervous about when we first enrolled was the pace. I was worried that, with me overseeing their education for the first time, and with their schoolwork being all online, that they would fall behind by getting distracted or spending too much time on one subject. But because of the flexibility, it didn’t matter what pace they were working at, as long as they were completing assignments on time.

One of the biggest benefits was the support my children received from their teachers – especially Vini. Vini can be a perfectionist because he wants to get everything right the first time. Seeing that Vini had not yet submitted an assignment, one of his teachers reached out to see how she could help. After I told her about his perfectionist ways, she provided him with some great advice and encouraged him to write his ideas down on paper. Her patience with him was incredible.

Another benefit were the digital courses. One day I heard Vini laughing when he should have been completing his schoolwork, so I went to investigate. What I found was that he was laughing and thoroughly enjoying one of his lessons. Vini learns through a variety of content in his courses – video, audio, quizzes, games, and more – and everything is integrated. Because he is interacting and enjoying the lessons, his comprehension deepens, and he finds new passions.

Q. What about communication with teachers? Do you feel you got enough individual time with them?

A. I feel like the teachers were very communicative, especially with me, which was a breath of fresh air. They kept me informed on how my children were doing and were there if I had questions or needed advice – always responding back to us within 24 hours.

Q. How did it feel to attend a virtual school? Did you feel socially isolated, and if so, what did you do to overcome that?

A. During the pandemic I think everyone has felt isolated to a certain extent. It has been a tough 18 months filled with unknowns, but because of the one-on-one time with teachers, live lessons, and courses that my children could interact with, they were able to stay energized with their schoolwork.

Additionally, one of Vini’s teachers wanted to get students even more excited about math, so she created something called “Fun Fridays,” which was an informal Zoom meetup where students would join and play math games together. It ended up being Vini’s favorite activity at FLVS and allowed him to interact with other students.

Q. How did you feel about the quality of education your child received after the first year at FLVS? What, if any, metrics support your opinion?

A. The quality of education is really good. The system provides all the support you need. Besides the lessons, FLVS also has live lessons, videos, interactive activities, and teacher support. Last year, my oldest daughter was enrolled in four honors classes and all her grades were A’s. All my children are straight A students. But it is not only about grades, it is about learning, and they are really learning at FLVS.

Q. Why did you decide to enroll your children at FLVS a second year?

A. We decided to attend FLVS a second year because our children discovered a new way of learning that has worked well for them. They enjoy the classes, their teachers, and the flexibility of learning online.

Q. How is this year going? How is it comparing to last year?

A. Last year was a learning year for all of us. We learned about rhythm, pace, and how to get the best out of the FLVS platform. This year, the kids know exactly where to go in case they need help. It’s definitely going smoother than last year. They have also begun to understand the perks that they have attending a virtual school compared to a traditional one. Not having to stick to a tight schedule sounds fun, but what is important is that they learn to pace themselves and be responsible. It is not easy at first, and it is still a learning process, but they have matured a lot.

Q. What guidance would you give another parent who is looking for an alternative to a traditional school?

A. For any parents considering online learning for their children this school year or in the future, my advice would be don’t be afraid to do it. You will have the support you need, the courses are interactive and engaging, your children have the flexibility to work from anywhere, and they will learn new skills like self-motivation, responsibility, and creativity. Also, don’t be afraid to ask questions. The teachers at FLVS are just a quick phone call or text away and can help with anything that you or your children are struggling with.

While many learning pods that existed before the pandemic as afterschool programs or summer camps returned to their pre-pandemic programming, others, like this one in Calabasas, California, continued to operate, offering promising innovations on the original concept.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Alice Opalka, a research analyst with the Center on Reinventing Public Education, appeared today on The 74. It originally published on CRPE’s education blog, The Lens.

Over the past school year, the Center on Reinventing Public Education has tracked how pandemic learning pods evolved from emergency responses to, in some cases, small, innovative, and personalized learning communities.

This summer, as COVID-19 vaccinations increased, it seemed like the major impetus for these efforts was fading from view. We turned to our existing database of 372 school district- and community-driven learning pods to answer this question: How sustainable is the learning pod movement?

That question has taken on greater urgency as new, more transmissible variants of the virus raise new safety fears — especially for children too young to be vaccinated — and school systems explore options for families who remain hesitant to return to normal classrooms.

Our analysis found clear evidence that a little over one-third of the learning environments we tracked operated through the end of the school year. But we also identified promising evolutions of the original concepts that will continue into next school year. While, in the short term, most students will likely return to some sort of “normal” school model, the lessons of these small learning communities have the potential to persist in new ways.

Public school learning models changed considerably between our last update in February and the end of the school year. Though there were school districts that remained fully remote through the school year, by the end of the year most districts had added at least some in-person options which would, in theory, minimize the need for many of the learning pods in our database since many of them were designed to provide in-person support and internet connections to students who were learning remotely.

If pods continued after school districts resumed in-person instruction, that offers some evidence families valued the alternatives to traditional classrooms that they provided.

We found that 37% of all learning pods identified in the database operated through the full 2020-21 school year. Half of the pods were “unclear,” meaning there was no clear end date to the pod-like offerings, but also no clear indication they continued through the end of the year. Only 12% had definitively closed at some point before the end of the year.

It’s possible that many of the “unclear” pods also ceased school-day support but never updated their websites or social media to make the announcement.

To continue reading, click here.

A new report from researchers at Stanford University shows about 300,000 students did not attend public school last year because their schools didn’t offer in-person learning, a finding that accounts for about one-quarter of the country’s overall public school enrollment drop during the pandemic.

A new report from researchers at Stanford University shows about 300,000 students did not attend public school last year because their schools didn’t offer in-person learning, a finding that accounts for about one-quarter of the country’s overall public school enrollment drop during the pandemic.

The study examined the impact of school-reopening decisions made by 875 public school districts – remote only, in-person or hybrid – on their enrollment levels, drawing on data sources that tracked district enrollment trajectories by grade level as well as the instructional mode chosen by districts for the 2020- 21 school year. Districts studied tended to be more urban and suburban, enrolling more students of color than the nation as a whole, though their pre-pandemic enrollment trends tracked the country overall.

Among the report’s key findings:

The researchers acknowledged that the effects of those policy variables on enrollment decisions are uncertain; parents, for example, who may have been comparatively likely to keep their child enrolled in a district that offered only remote or hybrid schooling may have viewed it as a way to safeguard the health of their children by reducing the risk of COVID-19 infection.

They further acknowledged that district decisions to offer alternatives to traditional instruction could have reinforced this sort of response by creating a salient signal of the risks associated with face-to-face instruction, i.e., an inferred recommendation.

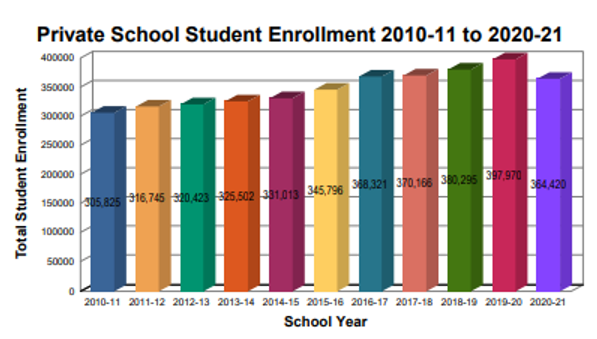

COVID-19 rocked K-12 school enrollment overall last year, but private schools were hit especially hard as enrollment declined for the first time in more than a decade.

COVID-19 rocked K-12 school enrollment overall last year, but private schools were hit especially hard as enrollment declined for the first time in more than a decade.

A new report from the Florida Department of Education shows private school enrollment fell by 33,500 students, the steepest decline observed in the last 20 years.

Public schools, which include charter schools, saw a decline of 84,355 students, or minus 2.9%, during the pandemic. Private school enrollment declined 8.4%.

The report also shows the number of private schools in the state declined by 82, while private schools’ market share declined from 12.2% to 11.5% of all PreK-12 students in the state.

Home education proved to be a popular education alternative for public and private school students alike, growing by more than 37,000 students.

Florida Virtual School also saw a sharp increase in enrollments last year – 5,644 more full-time students over the previous year, a 98% spike, with more than 231,100 new course enrollments, a 57% increase in its part-time FLVS Flex program.

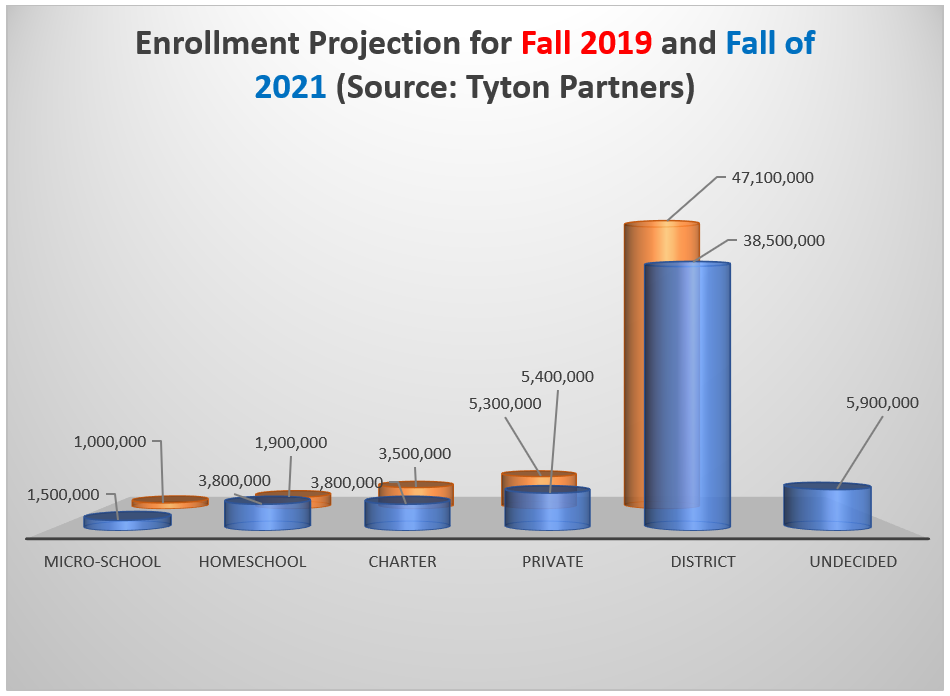

The advisory firm Tyton Partners has released the second installment of its “school disrupted” study, which takes a deeper look at the drivers and barriers parents experienced when making educational decisions for their children in the face of COVID-19 challenges, as well as how their experiences will continue to shape the way they approach their children’s education after the pandemic subsides.

The advisory firm Tyton Partners has released the second installment of its “school disrupted” study, which takes a deeper look at the drivers and barriers parents experienced when making educational decisions for their children in the face of COVID-19 challenges, as well as how their experiences will continue to shape the way they approach their children’s education after the pandemic subsides.

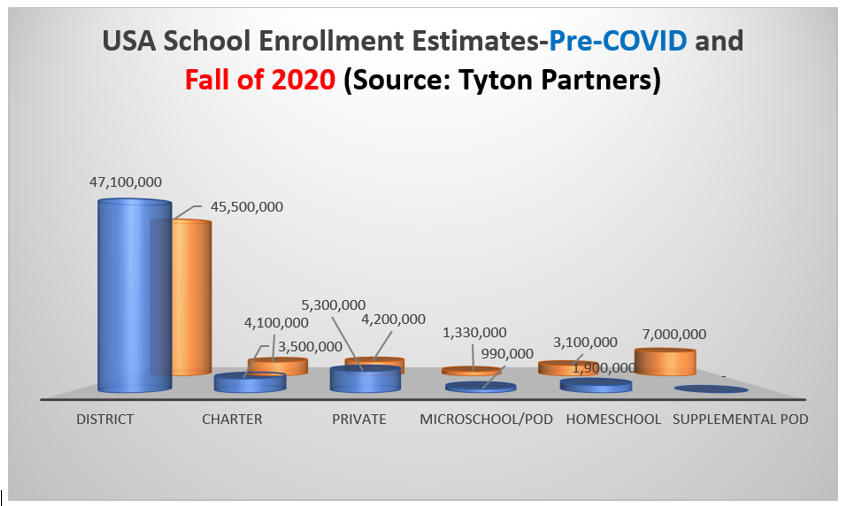

Part 2 of the study includes estimated enrollment by school sector for this fall. Among families who have made decisions for their children, approximately 72% chose a district school, with 28% choosing something different. If the 5.9 million families who are still undecided break in similar fashion, district enrollment could dip to levels not experienced in this millennium.

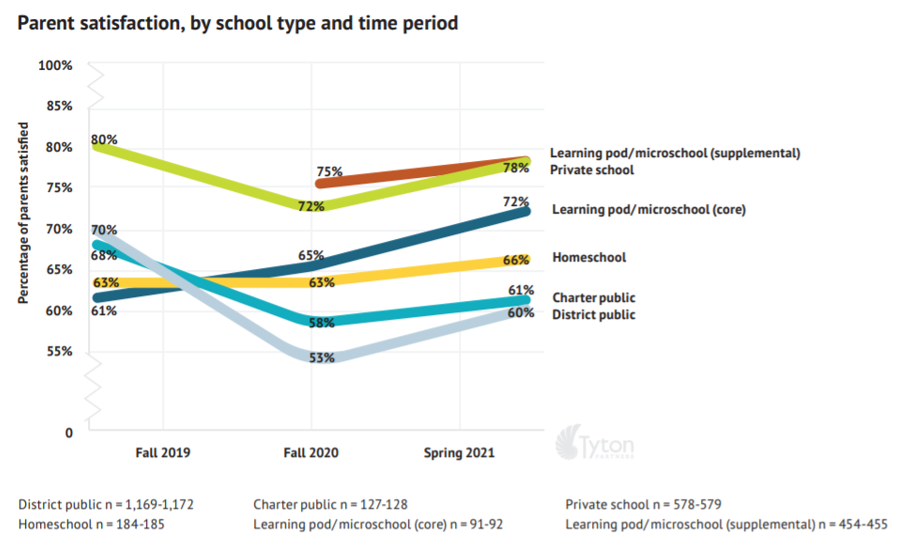

The survey also measured parental satisfaction by school sector from the previous school year. Satisfaction with supplemental pods, in which students remain enrolled in the distance learning program of a school but gather in groups with adult guidance, posted at 78%, tied with private school satisfaction. Parents whose students participated in pods full time followed with 72% satisfaction. Satisfaction with charter and traditional public schools was least favorable, at 61% and 60%, respectively.

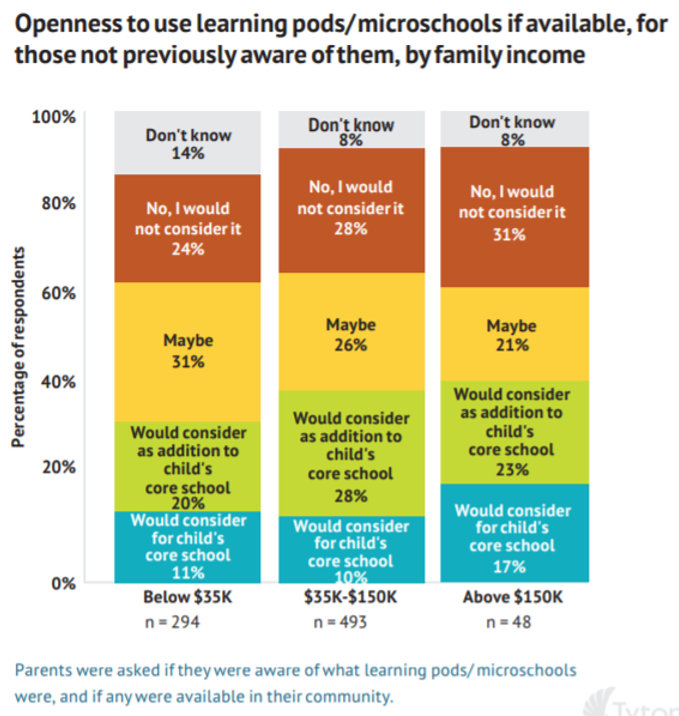

Additionally, the survey queried families who were unaware of learning pods and micro-schools on their potential interest. A majority across all income levels expressed interest in utilizing pods and micro-schools for either supplemental or full-time attendance.

The study is well worth reading in full. The results show robust growth in alternative schooling and home-schooling during the pandemic among those who have participated as well as from those who did not. It also shows a great deal of dissatisfaction with traditional schooling.

Put all this together with a baby-bust that began in the Great Recession period and I’m willing to go all in on the following bet: Peak district school attendance lies at some point in the past for anyone old enough to read this post.

Ironically, it was the very groups that accused their opponents of attempting to “destroy public education” that have inflicted this exodus upon the system they claim to support.

COVID-19-related challenges to K-12 education resemble the type of intense dust storms that are carried on an atmospheric gravity current, also known as a weather front.

Back in 2015, I studied Census forecasts about predicted looming increases in state elderly and youth populations. Based on those forecasts, it was easy to see trouble ahead.

Six years later, it’s obvious that trouble did indeed arrive, in some cases as expected and in others, in a different form.

These grim forecasts remain on track, but an unforeseen “Baby Bust” and a global pandemic threw in some unexpected curves. The 2020s were always going to be a challenging decade for American K-12, and the chaotic opening to the decade should not overly distract us from understanding the bigger picture issues.

First off, there are the short-run issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic:

Public school enrollment fell during the 2020-21 school year. Parents around the country kept their young children out of kindergarten. This fall, school may have a larger-than-average kindergarten cohort as students return and a smaller-than-average first-grade cohort.

Schools could accommodate this situation in part by shifting first-grade teachers into kindergarten assignments. This likely will happen in many places, but then again, signs indicate parents may have other ideas. Denver Public Schools, for example announced that applications for pre-kindergarten for fall 2021 have declined by 20%v.

Although it’s too early to get a firm picture on the data, many school systems may be headed toward a second consecutive year of declining kindergarten enrollment. COVID-19 vaccines have not been approved for use in young children. Although research indicates that the flu is literally deadlier to young people than COVID-19 and that school staff has had access to vaccines, many people remain concerned. As many as one-quarter of American parents have indicated they will keep their children home this fall.

Tyton Partners, an advisory firm serving clients in the education, information and media markets arenas, performed a panel study of enrollment decisions and education spending of a panel of parents last fall. Based on parent response, the firm estimated trends illustrated in the chart above for fall 2020. The closer you study these trends, the more dramatic they seem; large increases in home-schooling, charter school attendance and micro-schools.

Nationally, charter schools took more than a decade and a half to reach the same 1.3 million student mark reached by full-time micro-school students last fall.

Almost out of thin air, 7-million students, by Tyton’s estimate, attended supplemental pods last fall. These students remained enrolled in a pre-existing school through digital learning arrangements, but participated in small “pandemic pod” gatherings for socialization and custodial care.

Scattered formative assessment data from pods during fall 2020 have been released, and the news is academically encouraging.

An investigation of student engagement in Chicago Public Schools with distance learning, for instance, found that one-quarter of students failed to log on once during the week studied. Students “enrolled” in a system continued to generate resources for that system, but whether they actually engaged in any learning is an entirely different question.

The longer-term age demography challenge involves an ever-growing cohort of aged retirees and funding imbalances in retiree entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare. At any given time, working aged people carry the primary financial burden of providing the resources to pay for the education of the young and the retirement of the elderly.

Much of the working-age population of the later 2020s, 2030s and 2040s just took an impromptu break from schooling.

The ability of American policymakers to sustain the social welfare state always has been a bet on the ingenuity and productivity of future generations. The pre-pandemic school system did far too little to instill confidence in this bet.

Shutting schools down and losing track of millions of students in the process makes matters worse still.

Our best hope for overcoming these challenges lies in an anti-fragile system of K-12 education that grows stronger in times of distress. Federal K-12 emergency funding, however, seems likely to simply preserve the past rather than bridge the way to a brighter future.

Bottom-up pressure, however, points entirely in the opposite direction. An entirely new sector of micro-schools has grown, home-schooling has surged, and state lawmakers have enacted the most far-reaching set of education choice bills in the nation’s history.

Dylan Wood, an incoming sophomore at Land O'Lakes High School's pre-International Baccalaureate magnet program, shows the books his father, Mark Wood, encouraged him to read this summer. Titles include John Steinbeck's "Of Mice and Men" and John Knowles' "A Separate Peace."

Editor’s note: This commentary from Mark Wood, a professional writer and editor with an educator’s heart, is redefinED’s salute to all dads as Father’s Day approaches. Wood, who respects teachers, values learning and makes sure his son does all his homework, is married to Lisa Buie, senior writer for redefinED.

It was hard for me to imagine that I could possibly spend more time with my son, Dylan.

In early 2020, I was picking him up every day from school. In the car, we would perform a daily debrief through which I would hear about every class, every assignment and every homework task. After sharing dinner, I would ferry him to his Boy Scout meetings every Tuesday. Every Monday, Thursday and Friday I watched karate practice.

On weekends, we would share movie nights with mom, attend church, pursue our hobbies or compete in a karate tournament.

I always considered myself one of the lucky dads. My job as a writer and editor afforded me maximum flexibility. Dylan’s sick at school? No problem, I got this. Scouting campout starting Friday? I’ll just work remotely. Even when Dylan was a baby, I negotiated a work-at-home arrangement to keep him out of day care as long as possible. A congenital partial hearing loss was my motivator.

I spied as he pinched his first cereal puff in his tiny fingers and deposited it into his mouth. I watched as he took his first wobbly step.

Last year, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, I learned that I only had begun to spend time with Dylan.

As eighth grade continued into the fourth quarter, all students in Dylan’s school district were required to take their classes online. I worked at home and kept watch. When the number of cases continued to spike, my wife, Lisa, and I decided that we would choose our district’s option for Dylan to learn remotely via Zoom classes. In this arrangement, his district would let students log into in-person classes via the upstart computer platform. In some cases, masked teachers would instruct students sitting at desks and peering through screens. Some teachers had all-Zoom classes and could doff their face coverings.

As Dylan now was a ninth-grader in a rigorous pre-IB magnet program, we worried about academic struggles and logistical problems. So I appointed myself principal of our little home-based school. Order would be maintained. Discipline assured. And time with my son multiplied exponentially.

Now the first year of high school is behind us. Dylan excelled, earning four A’s and two B’s in a program known for its demands.

Evidence indicates that a legion of fathers have joined me in increasing their time with their kids and taking a more active role in their education.

A new poll conducted by Pearson and its online school, Connections Academy, shows that 89% of fathers report that being involved in their children’s education has helped them grow closer to them. A similar survey that the company conducted in March showed that 76% of parents said supporting their children’s learning at home was gratifying. I suspect many dads, like me, also were required to work at home for an extended time, putting them close by as they and their kids navigated Zoom meetings and enjoyed casual environs.

Some of the results confirm what I’ve known since my son entered preschool in 2008: Taking an active role in your child’s education will draw you closer to them and help you understand them. It also will make you part of your child’s “education team.” Not everyone is a teacher, but I believe everyone, particularly parents, can be “educators.”

Results show that 90% of fathers surveyed say they understand their child better. Slightly fewer (89%) said that being part of the learning experience helped them grow closer to their child.

More than eight out of 10 dads agreed that their children adapted to online learning well and that it helped boost their child’s confidence and time management skills.

For many, including our family, pandemic-related distance learning choices will not be offered in the 2021-2022 school year. Frankly, our son is eager to get back to in-person learning to fully experience the social advantages that high school offers. We don’t blame him.

With this return to normal, nearly three out of four fathers surveyed worry that they won’t be able to maintain the same level of involvement in their child’s education. I do not necessarily share their concern.

Sure, I won’t be able to pop my head in my son’s bedroom between classes for a quick update, but you can rest assured that I’ll stay involved. I have served on school advisory councils during Dylan’s elementary, middle and now high school years. I’ll continue to quiz him in the car about classes and homework on the way to after-school activities.

Meaningful involvement will take a little more effort this fall, but I hope dads — and moms — will remember the fulfillment they got by having more access to their children’s education this past year.

Parents can continue that access and influence by talking daily with their children and keeping communication lines open with teachers and administrators.

School may be a building, but education is an endeavor. And all of us are called to play a crucial part in our child’s learning. I hope all parents will join me in being educators.

Editor’s note: This piece from Michael J. Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, appeared recently on Education Next.

Editor’s note: This piece from Michael J. Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a research fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, appeared recently on Education Next.

A crisis like a pandemic can spark unpredictable changes in trends and behavior, like widespread mask wearing in the United States. But it also can accelerate changes that were already underway but otherwise would have taken root much more slowly.

For example, working remotely was a relative rarity in early 2020; now many organizations may never again expect all employees in the office five days a week. And outdoor eating spaces, an occasional curiosity in some cities, have popped up nearly everywhere. Lots of cities and small towns have made it clear that they would like to keep this innovation even after the crisis recedes.

So too in the world of K–12 education, where some new pandemic-era practices are likely to persist for the long term.

Some of these are simple and straightforward. Using Zoom for parent-teacher conferences and PTA meetings makes life easier for working parents. Online curriculum materials rather than printed textbooks may also have staying power, since so many students have Chromebooks or other internet-connected devices.

Others are more complicated, such as recording a school’s or district’s best teacher giving key lessons and using those videos in multiple classrooms. That frees up other teachers to provide support and individualized instruction—a nimble, but politically sensitive, way to rework teachers’ roles and use technology to improve instruction (see “How Big Charter Networks Made the Switch to Remote Learning,” feature, Spring 2021).

But as both common sense and classic conservatism would submit, not all of the changes that have occurred in education during the pandemic are positive. And just as there are some innovations that we should strive to maintain in the post-Covid era, there are others we should leave behind.

Here are my top five—including several that are close cousins (perhaps evil cousins?) of more promising ideas.

To continue reading, click here.