Editor's note: This commentary by Laura Waters, a mom, education blogger and former school board president in New Jersey, first appeared March 25 on EducationPost. The daughter of New York City educators and parent of a son with special needs, she writes frequently about the need to listen to families and ensure access to good public school options for all. Her observations on school inequities in her state are arguably observable nationwide.

Editor's note: This commentary by Laura Waters, a mom, education blogger and former school board president in New Jersey, first appeared March 25 on EducationPost. The daughter of New York City educators and parent of a son with special needs, she writes frequently about the need to listen to families and ensure access to good public school options for all. Her observations on school inequities in her state are arguably observable nationwide.

I live right off Route 206, a mostly two-lane road that begins in the Pinelands of southern New Jersey, winds 130 miles north to Stokes State Forest, and ends in Dingman Township, Pa. One 12-mile stretch of 206 connects Princeton, Lawrence Township (where I live), and Trenton, the state capitol.

As COVID-19 affects, well, everything — here, we’re currently in something close to a lockdown, with a 158 percent jump in confirmed cases during the last three days — New Jersey’s educational inequities come into sharp relief.

Think of this stretch of Route 206 as an emblem of America.

Princeton Regional Public Schools, a district where only 8 percent of students are economically disadvantaged and 80 percent of 10th graders meet or exceed benchmarks in reading, created a “Pandemic Response Team” that has issued a 10-page booklet explaining how students will continue to learn at home. Every student has a laptop or iPad, as well as internet access; if necessary, the district will fill in any gaps. Special education students have daily to-do lists and “teachers will send individualized guidance and support to parents through email.”

The district website lists separate letters from each of its principals detailing daily expectations. At Princeton High School, for example, “teachers will post content … and [students] will have a minimum of one hour of coursework for each class each day.” At elementary schools, students will have four hours of coursework per day and “one or more of our teachers [will] check-in with each pupil and his or her family multiple times per week via telephone calls, e-mails, Class Dojo or some other means.”

Now let’s travel 12 miles south to Trenton where 70 percent of students are economically disadvantaged and 22 percent of 10th-graders meet or exceed benchmarks in reading. The district has a booklet labeled “Health-Related School Closures” that says, “a series of learning experiences has been created for students by grade levels.” There is a one-page letter from the superintendent that says “the current school closure is not a vacation” and “students are expected to log on to Google daily for at least four hours daily and complete assignments in Google classroom” using a one-page reference of free online education programs. If a family doesn’t have a computer or online access (for comparison, in demographically-similar Camden only 30 percent do), parents can “pick up a paper packet from their school.”

Or not. Just up the district website:

The district has exhausted all of the printed packets; the district is closed and our vendors have limited resources in printing out additional packets. Therefore, no additional copies are available until further notice.

If you are a Princeton High School student, you get six hours of online instruction a day and regular check-ins with teachers.

If you are a Trenton Central High School student who happens to have a laptop and access to the internet, you get up to four hours of online instruction with no assured teacher contact. If you don’t have a laptop and internet access you get nothing.

This disparity in opportunity and access was true before the pandemic, but now we see the gaps more clearly. Oh, the data was always there: according to state Doe, 72 percent of third-graders at this Princeton elementary school read at or above grade level; at this Trenton Elementary school, 11 percent do. Ninety percent of Princeton High graduates enroll in postsecondary programs but 51 percent of Trenton Central High graduates do. (It’s 12 percent at Trenton’s alternative high school where 445 students are enrolled.)

These starkly disparate numbers haven’t swayed New Jersey to do anything in the last half-century but throw more money at the problem with no impact on student outcomes. While we seem susceptible to bromides like those from the state teacher union that proclaim, “NJ schools rank first in the country,” parents stuck at home now have an unfiltered view of our deficiencies.

Of course, these opportunity gaps aren’t limited to a two-lane road in New Jersey. Camden superintendent Katrina McCombs says the school shutdown “has just exacerbated the inequalities.”

Colin Seale writes,

The coronavirus pandemic is revealing new layers of inequity that may end up setting us back even further. Education leaders are tackling the unexpected challenge of providing distance learning as the primary mode of instruction for weeks, months, and possibly the remainder of the school year. How can school systems that struggle to deliver equitable results in a standard brick and mortar setting overcome the added challenges inherent in distance learning?

Meria Carstarphen, superintendent of Atlanta Public Schools, told NPR:

The inequities that we often talk about have a spotlight during this crisis. So if you’re wealthy or of a better socioeconomic means, you can get an access to tests, still get access to the support you need for your students. But that’s not true in communities where there’s high poverty and high need.

We’re all trying to stay healthy and keep our loved ones safe. It’s hard to think beyond this day or this week. But I think we must. Jonathan Rauch of the Brookings Institute says “plagues drive change.” Rahm Emanuel says, “you never let a serious crisis go to waste. Things that we had postponed for too long, that were long-term, are now immediate and must be dealt with. This crisis provides the opportunity for us to do things that you could not do before.”

We have to do things we thought we could not do before. We have to drive change. Otherwise, your location on a 12-mile stretch of road represents whether or not your third-grader can read or your high school graduate will go to college or get a job. It may have taken a pandemic to enable us to see this clearly, but here we are. Do we have what it takes to address systemic inadequacies, to innovate and buck a broken system? I hope so, but I don’t know the answer.

Natalie Keime, ESOL coordinator and sixth-grade intensive reading teacher at Somerset Oaks Academy in Homestead, delivers a virtual lesson to her students from her home.

About a decade ago, Fernando Zulueta was making a presentation to school district officials in Florida about why his charter school support company, Academica, needed to expand into online learning. For one thing, he told them, charter schools serviced by Academica must better serve students who need flexibility because of their talents (say, an elite gymnast) or their challenges (say, homebound because of illness). For another, he said, you never know when a natural disaster – maybe even a pandemic – might necessitate a transition into virtual instruction.

Fast forward to coronavirus 2020.

Academica, now one of the biggest charter support organizations in America, was among the first education outfits in America to shift online as thousands of brick-and-mortar schools were shuttered. The company began planning for potential closures weeks in advance. And when the closure orders were given in Florida, it trained thousands of teachers, distributed thousands of laptops, and acclimated tens of thousands of students to a new normal – in a matter of days.

“I’m not a doomsday prepper,” Zulueta said. “But when you do the work we do, you have the responsibility to be prepared … and to evaluate risks and contingencies in the future.”

On March 13, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis ordered all public schools in Florida to extend spring break a week so students would not return to school. At the time, the vast majority of Florida districts were about to start their spring break, while a handful of others were ending theirs.

Most of the Academica-supported charter schools in Florida were still a week from break. But by March 16, about 40,000 of their 65,000 students logged into class from home. By week’s end, most of the rest had, too. Within days, Academica’s Florida schools were reporting, based on student logins, nearly normal attendance rates.

“I had a little bit of mixed reaction” when the call came to transition, said Miriam Barrios, a third-grade teacher at Mater Academy of International Studies, an Academica-supported school in Miami. Ninety-nine percent of Mater’s students are students of color; 97 percent are low-income. “A lot of these families don’t have computers. So, it was a little scary.”

“But overall things have gone so well, much better than I expected,” Barrios said.

“It ended up feeling a lot like being in school,” said Claudia Fernandez-Castillo, a parent in Miami whose daughters, ages 11 and 12, attend another Academica-supported school, Pinecrest Cove Academy. “They made the kids feel very comfortable with this massive change in their little lives.”

Academica services 165 charter schools in eight states, including 133 in Florida. Somerset, Mater, Doral and Pinecrest are its main networks. According to the most rigorous and respected research on charter school outcomes, students in all four networks are making modest to large gains over like students in district schools.

It remains to be seen how well schools in any sector respond to what is an unprecedented crisis, and what the impacts will be on academic performance.

School districts are mobilizing quickly. In Florida, most of them still have a few days to prep before the bulk of students return to “school” March 30. To date, there’s been little coverage of how Florida’s 600-plus charter schools are coping (though there’s been a glimpse here and there for charters elsewhere.) Ditto for Florida’s 2,700 private schools. Some are proving nimble and capable. But given the big resource disparities, it’s an open question whether others with large numbers of low-income students have the technology and support they need to turn on a dime.

For Academica, online learning is familiar territory. The organization supports three virtual charters in Florida. It offers online courses for students in its other Florida schools. For a decade, it’s also had an international arm, Academica Virtual Education, that serves thousands of students in Europe who need dual enrollment classes to earn specialized diplomas.

Given the events in China, Zulueta said his team began considering, in January, the possibility of school closures in America. The urgency ramped up in February, when the spread of coronavirus in Italy began affecting Academica students in that country.

In mid-February, Academica-serviced schools in the U.S. sent questionnaires to parents, asking if they needed devices and/or connections for distance learning. They ordered what they needed to fill the gaps. When Gov. DeSantis made what was effectively a closure announcement March 13, Zulueta said, “we were already ready to rock and roll.”

The day after the announcement, Academica used online sessions to do basic training in online instruction for 150 administrators. Over that weekend, it trained 3,000 teachers. Meanwhile, schools distributed several thousand laptops to families, in some cases through drive-through pick-ups. Zulueta said the need ranged from 4 percent at some Academica client schools to 20 percent at others.

Schools also immediately let parents know what was coming Monday.

Zulueta, who has three daughters in Academica-serviced schools, witnessed the new normal at his kitchen table.

“They got up. They logged in. And they went right to class,” he said. His daughters and their classmates wore their usual uniforms. The schools did their best to stick to established bell schedules. “We wanted to keep it as close to what they did at school as possible.”

Like students at Academica-serviced schools throughout Florida, television production students at Doral Academy Preparatory High School have quickly adapted to a virtual learning environment.

Academica uses an online learning platform it created itself. It’s integrated with a number of other tools, including Zoom, the video conferencing software with the “Hollywood Squares” look.

Fernandez-Castillo, the mom at Pinecrest Cove Academy, said she watched over the weekend as friends who are Academica teachers practiced the new online platform with each other. Barrios, the Mater teacher, said she contacted her students’ parents after her training on Friday to tell them she would be testing the platform at 8 that night if they and their children wanted to join. Eight to 10 families did. But she still had some anxiety about Monday morning.

“I thought it was going to be a freak show,” Barrios said. “The computers are going to crash, the kids are not going to log in … “

That’s not what happened. Monday morning was “a little jagged,” she said, because some students experienced technical difficulties and couldn’t log in right on schedule at 8:30. But by 8:50, 90 percent of her students were in. “It was amazing,” she said.

Barrios and other teachers used Monday to get their students familiar with the new set up. Any glitches, like problems with Internet access, were minor, she said. Over the next few days, she and her students quickly cleared little hurdles, like students learning to keep their mics on mute until it was their time to speak, and how to use chat functions to indicate they had a question.

Barrios doesn’t think there’s a long-term substitute for the dynamics of an in-person classroom, where students, in her view, can more easily “bounce ideas off one another.” But as a next best thing, she said what her school is doing is far better than nothing, and not bad at all.

Fernandez-Castillo agreed, and pointed to other upsides. “Everybody’s thrilled with the way this has been done,” she said, referring to other parents. “I think it glued the (school) community together even more.”

Coronavirus is interrupting life in general and education specifically. As parents in the U.S. adjust to school closures and the potential for their K-12 child’s coursework to continue online, families should come to realize that they will be exposed to more of what their children are learning.

Coronavirus is interrupting life in general and education specifically. As parents in the U.S. adjust to school closures and the potential for their K-12 child’s coursework to continue online, families should come to realize that they will be exposed to more of what their children are learning.

For some, this will be new.

Wall Street Journal editor Serena Ng wrote recently from Hong Kong, where schools have been closed since Feb. 3, that she now can “see every detail of every lesson.” Ng says, “I previously had only a vague idea about what they were learning in school.”

All parents should be able to know what their children are learning, and for those paying attention in the coming weeks, the virus offers a chance for them to do just that. Working parents who juggle jobs and their children’s school activities while managing a home haven’t been neglectful if they don’t know what happened in fourth-period math on a given day (try asking a teenager what happened in class). Some simply have relied on schools to decide on instruction.

For others, this focus on content has been there all along.

March 2-4, the Institute for Classical Education and the Great Hearts Foundation held the National Classical Education Symposium, an event featuring sessions on teaching the Great Books, from “The Confessions of St. Augustine” to “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Great Hearts’ charter schools, which started in Arizona and have expanded to Texas, base their curriculum on these works. (You can find a complete list of the books students will be studying here.)

School districts are not always so transparent. As Matt Beienburg at the Goldwater Institute explained earlier this year, even if state law allows parents to review their child’s curriculum, they can do so only on school premises; in some cases and in some districts, there are limits set on when parents can see the material. Again, parents are not lazy if they don’t always know what is in their child’s syllabus.

When parents know what is being taught, they can effectively advocate for meaningful change. The reading wars over phonics versus whole language instruction are still with us today, while the Common Core debates over a national curriculum have simmered in time for everyone to scrutinize the New York Times’ 1619 Project.

The Project, a set of essays accompanied by K-12 curricular materials, “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Slavery and the racism that followed are a blight on our nation’s past, but the Times has taken the idea too far according to many scholars. Pulitzer Prize-winning historians, leading intellectuals and even the Times’ own fact-checkers have criticized the essays, citing inaccuracies.

For thousands of parents, the initiative is not just a problem for someone else’s school. The Times and the Pulitzer Center have successfully advocated for integrating the material into some of the nation’s largest and most-high profile school systems, including Chicago, Newark, Buffalo and Washington, D.C. In Florida, Florida A&M University highlighted the Project in September 2019 and has hosted events on the topic with Florida State University.

Critically, the Times on March 11 issued a correction to a central premise of the essays, saying that not all colonial revolutionaries fought the British to protect the institution of slavery. If the Times heeds other warnings from experts, this modest correction should not be the last. Meanwhile, the Times already has disseminated the original curricular materials to schools.

Developments like these are among the many reasons why the next few weeks of school closures and online instruction are an important opportunity for parents to catch up on what is happening at their child’s school. When parents send children back to brick-and-mortar schools, they should do so ready to raise questions, prepared with more information.

Parents practicing “social distancing” in the coming weeks should use this period to get closer to their child’s school assignments.

Florida Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran issued emergency orders Tuesday waiving certain requirements for education impacting both public and private schools. The order “waives strict adherence of Florida’s education code” for public schools, universities and colleges and private schools in Florida.

Florida Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran issued emergency orders Tuesday waiving certain requirements for education impacting both public and private schools. The order “waives strict adherence of Florida’s education code” for public schools, universities and colleges and private schools in Florida.

Specifically:

Though not specifically mentioned in the order, Step Up for Students, the nonprofit scholarship funding organization that hosts this blog, confirmed that private schools that have access to Title II funds may coordinate with their local public school district to use the unspent funds to help students purchase electronic devices to provide educational services virtually.

Step Up administers several private school scholarship programs in Florida including the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship which funds more than 100,000 scholarships for low-income students.

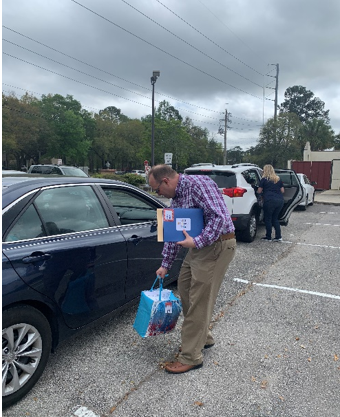

Diocese of St. Augustine superintendent Deacon Scott Conway helps load supplies in the carline at St. Joseph Catholic School as parents and students prepared to transition to an online learning environment from their homes.

Like all Florida public and private schools, Catholic schools, which educate about 1.8 million students nationwide and about 65,000 throughout the state, had mere days to move from in-person teaching to digital platforms once schools closed due to coronavirus.

As word of the closure came, National Catholic Education Association president Thomas Burnford offered encouraging words to Catholic school educators via a video on the NCEA website, acknowledging this would be a difficult time for them. But he also noted it would be an opportunity for Catholic schools to shine by connecting with students in creative ways.

Palmer Catholic Academy in Ponte Vedra Beach, about 22 miles southeast of Jacksonville, quickly rallied to the call. The school serves 449 children from PK4 through eighth grade, 22 of whom participate in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. Five students participate in the Gardiner Scholarship program for children with unique abilities, also administered by Step Up For Students.

Notified by their superintendent on March 13 that they would be teaching remotely by March 19, administrators worked through the weekend to make sure they would be able to launch training for their teachers. They were ready March 17, two days ahead of schedule.

Each morning since then, teachers have been taking attendance and smoothly rolling into their online lessons. At the end of the day, they collect work online and grade it, entering the data in their gradebooks.

Kindergarteners through fifth-graders are using a platform called Class Dojo, an educational technology communication app and website that connects teachers, students and families and uses features such as a feed for photos and videos from the school day. Sixth- through eighth-graders are using Microsoft Teams, a communication and collaboration platform that combines chat and video meetings and file storage. Students who didn’t have access to an iPad at home were able to borrow one from the school.

“I’ve been brought to tears several times watching the teachers recite prayers while our children follow along, and watching as they virtually walk them through their math sheets,” said parent Kelly Nelson. “The passion these teachers have and their love for their students is just radiating through the computer screen.”

Monica Begeman, marketing, admissions and advancement director, said teachers are doing a great job adjusting to an online learning world.

“The implementation has been a huge team effort. All of our teachers are on board and excited to ensure their students can continue learning,” Begeman said. “Going distance is a huge on-taking for our teachers, it is exhausting. We are so thankful to them.”

While Palmer Catholic Academy was gearing up for online learning, St. Joseph Catholic School in Jacksonville was undergoing a similar process. St. Joseph serves 497 students, 109 of whom participate in the Tax Credit Scholarship program.

St. Joseph’s adventures with online learning began March 16 when parents came to the school in small groups to pick up their children’s books and supplies. Over three hours, school staff assisted 330 families and made arrangements for 15 that were unable to come by. Principal Robin Feccit reports that in a very short time, every family had the supplies it needed to facilitate learning from home.

Students in grades K-2 are completing worksheet packets, while teachers utilize Facebook and YouTube and email parents daily. Students in the higher grades are using Google Classroom, a free web service that allows for paperless lesson creation, distribution and grading. To make sure everyone stays connected, Feccit conducts a morning meeting on Facebook Live.

“Our faculty, staff, students, and families have handled this transition very well,” Feccit said. “The first day was a little challenging as we figured things out, but Day 2 started strong, and we have been doing great since. The teachers are working so hard to keep contact with their students and help support student learning as much as possible.”

Families have been pleased and impressed, writing to the school and posting comments on social media. Parent Joanne Berrios, who has been homeschooling several children over the past few weeks, raved about the one-page worksheet prepared by teacher kindergarten teacher Deanna Kersten.

“It was extremely easy to transition to the new environment,” Berrios said. “I have been so impressed with how much Michael has learned in the past 133 days of school. Now I understand.”

Schools will reopen after we cancel the apocalypse. We just can’t be sure yet what that will look like.

Schools will reopen after we cancel the apocalypse. We just can’t be sure yet what that will look like.

I’m writing from my social isolation home base in Arizona, attempting to offer hope on the pandemic and passing along SeattlePI’s Christina Ausley’s list of good-news stories about the outbreak. According to Ausley, some reasons for optimism include:

Distilleries across the United States are making hand sanitizer instead of booze and are giving it away for free, as reported by NBC News.

Science Alert reports that doctors are developing passive antibody therapies to transfuse blood from those who have recovered from the virus. The antibodies from the transfused blood attack the viruses of the new host. From the article: “Nobody is expecting passive antibody therapy to become a silver bullet for the new coronavirus, but as something that could help us flatten the curve while other treatments are developed, it could make a huge difference, if we all act together – and act quickly.”

Live Science reports that scientists have figured out how coronavirus hijacks lung cells to produce more viruses, which can aid in the creation of drugs or vaccines.

The New York Post explains how Canadian scientists have isolated and replicated the Covid-19 virus, a major step toward development of a vaccine.

Vaccine trials are underway in China and the United States according to the New York Post and SeattlePI, respectively. Meanwhile, better tests with faster results are on the way according to News 5 Cleveland.

The Guardian reports that a Japanese flu drug is being tested to see if it impacts Covid-19. Two doctors write in the Wall Street Journal that some of these drug treatments show promise in shortening the run of the disease, which would be enormously helpful in preventing an Italian-style healthcare system disaster.

A few other developments: The White House says new legislation will allow tens of millions more protective masks to reach U.S. healthcare workers, and AccuWeather reports that a new study has found high temperature and high relative humidity reduces transmission rates. I never thought I would yearn for a Phoenix summer.

Physician Charlene Babcock describes in a YouTube video how innovators have figured out how to keep multiple patients alive with a single ventilator. Meanwhile, you can click here to see how the 3D printer community is making ventilator parts and improving ventilators.

The situation almost certainly will get worse before it gets better. I don’t know how this will end, but I’m confident that we are not going to spend the next 18 months in quarantine, and that schooling will return at some point after we parents all try to make sure learning continues on our own.

Hang in there.