When Florida lawmakers established the first statewide Charter School Review Commission in 2022.

The National Association of Charter School Authorizers also weighed in, saying that forcing school districts into sponsorship of schools they didn’t authorize would cause district officials to disengage, weakening charter oversight.

The National Association of Charter School Authorizers also weighed in, saying that forcing school districts into sponsorship of schools they didn’t authorize would cause district officials to disengage, weakening charter oversight.

That was before Susie Miller Carello showed up. Before becoming executive director at the newly established Florida Charter Institute, she spent 12 years leading the Charter Schools Institute at SUNY, the largest higher-education authorizer in the country, and earned the moniker “America’s Authorizer.”

Under her leadership, New York choices, quadrupled enrollment, and significantly improved student achievement. By the end of her term, she helped authorize 221 schools that enrolled 120,000 students.

A 2023 study by the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO) showed that New York, known for highly acclaimed charter networks such as Success Academy and Uncommon Schools, led the nation in outperforming their district school peers by the largest margins.

Carello’s job as chief of the Florida Charter Institute is to recommend to the seven-member statewide charter review commission whether to approve a proposed charter’s application or send the founders back to work on a plan that passes muster.

Since this institute began its work in 2023, would-be charter schools have submitted 22 applications. Just two made it to the commission for a vote. One of those was approved by the commission, the other rejected. Those who filed the other 20 withdrew their proposals after hearing Carello’s feedback.

“We’ve been very choosy,” Carello said. “We are committed to being very thorough and investigating the people who want to affect the lives of Florida children and gain access to millions in public funds to make sure they have not only a good design, but also that they have the capacity to put that good design in place.”

Statewide process more than a decade in the making

Efforts to establish a statewide review process that bypasses sometimes hostile local school boards stretch back nearly two decades. In 2008, a state appeals court struck down efforts to create a statewide charter school board like the ones in Massachusetts or Arizona.

In 2022, the Florida Legislature established the Florida Charter Schools Review Commission, with the institute as its administrative arm. The commission reviews applications from charter operators and authorizes them to operate. Once authorized, the local school district becomes the sponsor and supervisor for the charter school and is responsible for monitoring the school’s progress and finances and providing certain services.

The state also has now allowed state colleges and universities to authorize and operate charter schools.

Multiple pathways reduce the chances that school board politics could block a new school. State charter commissions also have specialized staff who evaluate charter schools full time, while school district officials are often burdened with other responsibilities.

The main charge from detractors was that allowing multiple pathways for charter schools would roll out the welcome mat for questionable operations. Two years in, that hasn’t been the case.

A statewide process also allows one-stop shopping for charter networks that seek to open locations in multiple counties instead of forcing them to file separate applications in each school district.

Newberry community rallies to support proposed new charter school

Carello’s and the commissioners’ high standards were on display at their first official meeting last month.

Carello presented two applications. The first came from the Newberry Community School in Alachua County, where a group of parents and teachers narrowly to turn the district elementary school to a charter school.

The Alachua County School Board opposed the application and has since voted to appeal the state Charter Review Commission’s unanimous approval to the state Board of Education.

However, Newberry city officials expressed strong moral and financial support. Former state Rep. Chuck Clemons, who represented the local House district, and other local leaders laid out the school plan, including a $2 million loan from the city and $180,000 in private donations. Teachers and staff would also receive pay raises that matched the district’s as well as the same benefits offered to city employees, including health insurance and a retirement plan. School employees enrolled in the Florida Retirement System would be allowed to remain.

The level of community support impressed commissioners.

“It was awesome to see the partnership that they have with the city of Newberry,” said Commissioner Sara C. Bianca, one of seven commissioners appointed by the state Board of Education in 2023. “The mayor of Newberry and two city commissioners were there, and they were just excited.”

Other Florida cities, like Cape Coral and Pembroke Pines, operate municipal charter networks, but Bianca said the structure of the Newberry partnership “feels unique,” and she’s curious to see if other cities follow suit.

‘Inconsistent and incomplete’

The second application, which commissioners unanimously denied, came from Bradenton Classical Academy, proposed as a Hillsdale College Barney Charter School. While Carello listed the Hillsdale affiliation as a strength, it wasn’t enough to give Bradenton the green light.

The evaluation form, signed by Carello, included concerns about its educational program design, which it said aligned poorly with state standards, and described staffing and budget plans as “inconsistent and incomplete.” The evaluation also cited the safety plan as “lacking in detail” and potentially jeopardizing student safety.

“Collectively, these gaps highlight the need for significant improvements before the school can be deemed operationally and academically viable,” the evaluation said.

Carello explained later that this was the second time Bradenton Classical had applied through the Florida Charter Institute after being denied by the Manatee County School District.

“They were victims of many different versions of the application,” Carello said. When leaders first applied, she said the institute offered advice and sent them back so they could improve the plan and resubmit for a better chance of approval.

She likened the best business plan to a spider web, where every strand is connected. When touched, the web might jiggle but still holds together.

The Bradenton Classical officials resubmitted a plan that didn’t “hang together.”

Though charter applicants must clear a high bar, the institute provides resources and support for a successful outcome. However, Carello never lowers that bar once a school wins approval.

“The charter initiative was to allow people to try out innovations. They got five years to try them out and if they made progress, that was great. And occasionally, there was a school that didn’t, and we closed them down.”

Last week, I documented the sad decline of charter school laws passed since 2000 if you actually want laws to produce charter school seats. If you prefer to mostly go through the motions of having a “charter law” without many actual schools, or in Kentucky’s case any charter schools, then the post-2000 laws have been a rousing success.

Last week, I documented the sad decline of charter school laws passed since 2000 if you actually want laws to produce charter school seats. If you prefer to mostly go through the motions of having a “charter law” without many actual schools, or in Kentucky’s case any charter schools, then the post-2000 laws have been a rousing success.

Mistakes are not, however, limited to initial laws and a rediscovery of some guiding principles for charter schooling seems long overdue.

Adam Smith wrote: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

He went on to explain that these conspiracies cannot succeed without the use of government. Thus, charter schooling fell under the sway of a Baptist and Bootlegger coalition and has been ailing ever since.

The Baptist and Bootlegger coalition aims not just to limit competition for district schools, but also competition for preexisting charter schools. Let’s simply observe that some charter organizations have a legal department to cut and paste sections of their last 800-page application into a new 800-page application. They can then assert, without any backing evidence mind you, that such an ability is an indicator of “quality.”

The charter movement, if vitality is to be regained, must rediscover a dedication to competition. Currently, parents are clamoring for new private school legislation and seem relatively indifferent to charter school legislation. Given that decades have passed since a state passed a charter law creating more than a mere smidge of charter school seats, one can hardly blame them.

Multiple sources of authorization constitute a key design feature of charter legislation, and one that charter advocates have inadequately communicated to legislators. For example, Oklahoma legislators are currently considering revamping their charter authorization practices. The legislation creates an alternative to school district authorization (which is good) but only creates one such alternative, which is not so good.

Oklahoma lawmakers will have to think deeper if they are to avoid the fate of lawmakers in Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Washington and others who passed charter legislation only later to ask: Where’s the seats?

Originally, the thought behind multiple authorizers was to stop the Baptists (in this case unions and their fellow travelers) from cutting off authorization. Now, charter advocates must guard against this and Bossy McBootleggerpants from undermining charter authorization.

Originally, the thought behind multiple authorizers was to stop the Baptists (in this case unions and their fellow travelers) from cutting off authorization. Now, charter advocates must guard against this and Bossy McBootleggerpants from undermining charter authorization.

It’s been two decades since a state passed a charter school law that managed to somewhat thwart the B/B coalition. Let’s hope Oklahoma will consider starting a new trend.

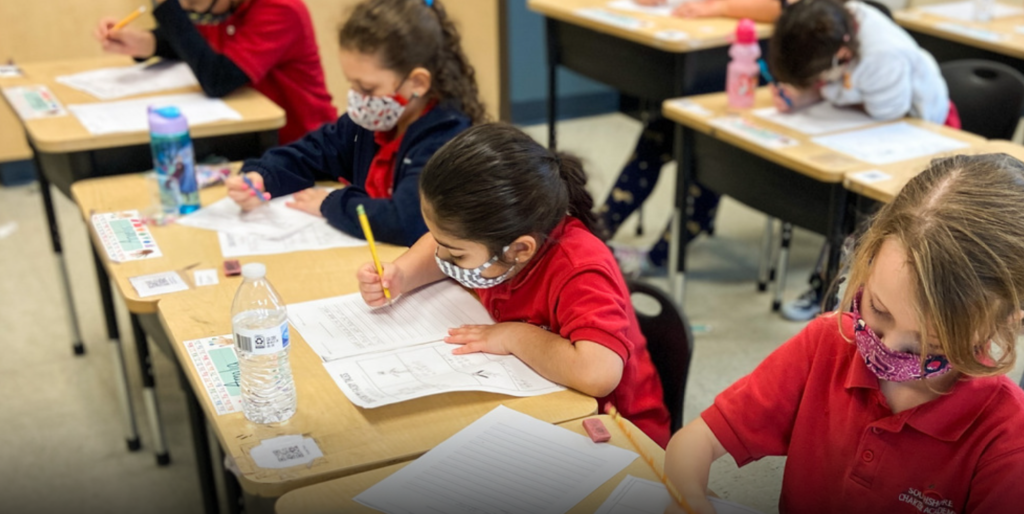

Southshore Charter Academy in Riverview, Florida, was one of four charter schools whose renewals were denied by the Hillsborough County School Board last summer. The district eventually reversed the decision.

Editor’s note: This commentary from three leaders in the charter school arena – Melissa Brady, executive director of the Florida Association of Charter School Authorizers; Alex Medler, executive director of the Colorado Association of Charter School Authorizers; and Tom Hutton, executive director of California Charter Authorizing Professionals; appeared Monday on The 74.

There is a persistent myth in education reform circles that school districts hate charter schools and cannot be trusted as charter authorizers if the sector is to succeed.

This myth obscures important realities — and opportunities — for the charter movement. These are challenging times for all public schools, and forward-thinking districts want to ensure that local charter schools have the support they need to succeed for students.

First reality check: School districts are central to charter authorizing.

About half of charter schools are authorized by districts, and nearly 90% of authorizers are districts. In many states, they are the primary or only authorizers. As leaders of state-based associations of district authorizers in Colorado (which has among the largest share of public-school students in charters), California and Florida (which have some of the nation’s largest charter sectors), we work with district leaders who recognize charters as vital parts of their local school systems.

These leaders do not consider themselves pro- or anti-charter; they simply want to perform their jobs as authorizers well, and they consider charter school students their district’s kids. When given the chance to improve authorizing, these districts embrace best practices like the National Association of Charter School Authorizers‘ Principles and Standards of Quality Charter School Authorizing, and our associations align our state-level supports for authorizers with NACSA’s approach.

Second reality check: The importance of school districts to the charter sector is only likely to increase.

In some states, major policy changes foreshadow further shifts to district authorizing. In 2016, Louisiana returned charter schools overseen by the state authorizer to the Orleans Parish. In 2019, Illinois decommissioned its state authorizer, transferring 11 state-approved charters to the State Board of Education.

While the Illinois State Board still hears appeals, districts will oversee future Illinois charter schools. That same year, California increased district discretion by narrowing criteria the State Board of Education uses to judge charter appeals and by transferring board-authorized charters to districts and county offices of education. In addition, a district may now reject a charter application based on its impact on finances and other community considerations.

To continue reading, click here.

Florida scores fairly well in a new-first-of-its kind report on charter school authorizing that's worth a look for anyone concerned about the quality of the state's charter schools.

The takeaway: Florida's constitution may be preventing the state from passing the best-possible charter policy, but the state could still be doing more to help improve the quality of charter school supervision.

The report, released last week by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers looks at states' policies for charter school authorizing - that is, the process for approving new schools, and then monitoring their performance and holding them accountable.

The group ranks Florida third of 17 states where school districts are the main authorizers of charter schools. The state gets good marks for its law such as a requirement that charters receiving two consecutive F's from the state must close. And the report praises the Florida Department of Education for this year developing a set of authorizing standards.

Still, it's worth unpacking why Florida doesn't score as well as South Carolina, the highest-scoring state in Florida's category. One key advantage: South Carolina has a state-run board that can authorize charter schools, meaning hopeful charters have a route to opening that doesn't run through the local school board.

When there's an alternative authorizer in place, good schools can open even if a local district wants to keep them out. It then becomes more feasible for the state to crack down on authorizers that allow too many poor schools to open.

If there's only one authorizer, threatening to strip its authorizing authority would mean shutting the door to new charters. As the report notes, "the absence of a quality authorizer in any jurisdiction can make the rest of the policies less important."

Florida lawmakers have tried to create a statewide charter school authorizer before, but they've been stymied in court because the state constitution gives districts the power to supervise all free public schools within their jurisdiction. As a result, "NACSA encourages Florida to revise its charter application appeals process to allow the appellate body to serve as the authorizer on appeal or to explore possible constitutional changes to allow a non-district alternative authorizer to do so."

But at a time when charters and districts alike are anxious about improving quality and stopping bad charters from opening, the report says the state can make some improvements without a constitutional change.

Florida policymakers, the report says, should look for ways to improve scrutiny of charter schools during the application process (what the report called "front-end charter school screening") and before their contracts come up for renewal (what the report calls "term-length oversight)."

The state could also start evaluating the quality of charter school authorizing in individual districts, and publishing information on the performance of the charters each district approves.

The sprawling, 125,000-student school district in Duval County, Fla., has a reputation for being particularly cold territory for vouchers and charter schools. But last month, its new superintendent recommended the school board approve a dozen new charter schools and, in doing so, sounded this refrain: We have to compete.

In an interview with redefinED, Nikolai Vitti said the competition injected into public education through expanded choice will improve schools in Duval, which has struggled with low-income students more than other big districts in Florida. He said he “vehemently opposed” limiting options for low-income parents. He spoke admiringly of the mission and innovative practices of the KIPP charter schools.

“The reality is, the market – meaning the structure of choice – forces me to compete, even if I don’t want to. And if I don’t compete, parents will continue to leave the school district,” Vitti said. “And so my role as superintendent is to improve our product.”

But Vitti, who previously served as chief academic officer in the Broad-Prize-winning Miami-Dade district, also offered a number of caveats. State rules tilt the playing field towards charter schools, he said. And in his view, the debate over them has been driven by perceptions of quality, not data.

“There are charter schools that have a track record of success, and particular charter schools that have failed, and failed in multiple areas,” he said. “Let’s not have an ideological conversation. Let’s have one based on data where we look at individual charter schools, individual traditional public schools, and ask the question: Who’s successful? Who’s not? And what’s the best situation for parents based on how they’re looking at it, and how the district as informed educators are looking at it?”

Vitti also offered a surprising take on who should authorize charter schools. In Florida, only school boards can do so – a situation that charter school opponents prefer, and one that may be tough to change because of restrictive language in the state constitution. But Vitti said unless changes are made to the charter application process – something that forces better dialogue between charters and districts – he’d rather have the state do the authorizing.

“I do believe there’s a way to create a balance between simply approving charter schools at the district level based on a boilerplate application process … and instead allow and require the charter school to be more strategic with the district,” he said. But “if we’re not going to create some kind of balance between that, then simply place the onus of the application process on the state. Because essentially that’s what’s happening already.”