In honor of 2023’s National School Choice Week, the Cato Institute published one of the first comprehensive timelines of school choice. Because opponents still seek to delegitimize school choice by accusing the movement of having nefarious origins, it's more important now than ever to establish its true history, one that extends back to the country's founding.

In honor of 2023’s National School Choice Week, the Cato Institute published one of the first comprehensive timelines of school choice. Because opponents still seek to delegitimize school choice by accusing the movement of having nefarious origins, it's more important now than ever to establish its true history, one that extends back to the country's founding.

But beyond the timeline’s stated purpose, to show that “empowering families to choose has a long history, both as an idea and in practice,” it also inadvertently makes a vital contribution to the history of political and educational thought by including Thomas Paine as a key figure in the early development of school choice.

Indeed, it is one of few sources I’ve seen (beyond my own work) to recognize that the first proposal for what we would now call an education choice scholarship program was made in 1791 by the Anglo-American rabble rouser.

Paine is a controversial figure; his prickly personality and attacks on organized religion earned him censure in the United States for hundreds of years. As a result, even the most historically-inclined school choice advocates have ignored Paine’s contributions, with Milton Friedman or occasionally John Stuart Mill getting all the credit.

They certainly deserve some recognition, but in the wake of School Choice Week, let’s join the Cato Institute in giving ol’ Tom Paine’s intellectual contributions the respect they deserve. Moreover, by considering his stance on education, school choice supporters can address some of the movement’s most glaring shortcomings.

Paine’s justification for his school choice proposal was not terribly dissimilar from the arguments school choice advocates make now. More specifically, Paine was concerned with education’s usefulness as well as how efficiently schooling could be provided. He wrote that “education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot, and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this is to enable the parents to pay the expenses themselves.”

Seems familiar, doesn’t it? Whether we know it or not, when school choice advocates argue that microschools can provide a valuable homeschooling-adjacent option for a local community of families, or that education savings accounts allow parents to cultivate an educational paradigm that is tailored to their children’s needs, we are echoing Thomas Paine.

Will this knowledge alter legislative battles or create new policies? Probably not. But anyone who advocates for a cause should understand that cause’s historical development, and that knowledge can allow us to dispel common nonsensical critiques.

One of the most common aspersions cast on school choice advocates is that we have it out for teachers. Of course, such criticisms are unfounded. Fortunately for us, Tom Paine was worried about teachers, too.

He observed that a wide variety of community members are capable of being educators, and that his ideal stipend to families would not only provide poor children with the education needed to prosper but would provide those teaching them with income and economic flexibility in their own right. Paine declared that “to them [children] it is education — to those who educate them it is a livelihood.”

Some contemporary school choice advocates, like Daniel Buck, formerly of Chalkboard Review, have made the argument that expanding education choice would actually benefit teachers. This line of reasoning remains criminally underutilized. Teachers all over America feel stuck and powerless in their current jobs, but despite widespread (but generally false) claims of a nationwide teacher shortage, most educators have many options but few real choices.

Turning back to Tom Paine really could make a dramatic difference, as education choice would offer teachers numerous additional learning models in which they may feel more fulfilled.

School choice advocates have done well to explain the real reasons why millions of parents around the country are pushing for more options for their children. But one chapter in school choice’s history must still be written.

By turning back to Tom Paine, school choice advocates can not only expand their potential audience, but also correct any historical misunderstandings before they reach the public square.

This 4,468-square-foot South Tampa home, located in the A-rated Mabry Elementary School zone, is listed for sale at $1.8 million.

When my husband and I bought our first home as newlyweds, we didn’t think to ask what public schools served the area. We were young, childless, and hyper-focused on our journalism careers, so our concerns centered on ease of commuting to work and shopping.

Then there was the fact that we had chosen to work in an industry that pays its workers barely a living wage, so our search was limited to a handful of neighborhoods.

We ended up selling that home at a loss but learned a valuable lesson: Because ZIP codes for the most part dictate where kids go to school, performance and reputation of public schools affect home prices, and those prices determine for the most part who gets access to those schools.

We were still childless but wiser as we house hunted after relocating to Florida. We asked questions about the reputations of the schools where students were zoned in our prospective neighborhood. We conducted online research and gleaned information from co-workers. In the end, an important point that factored into our decision: the development we liked was located near a site earmarked for a new elementary school.

I reflected recently on the difference between what I knew 20 years ago and what I know now when a Step Up For Students colleague shared a quarterly report delivered from a South Tampa real estate firm to homeowners in high-income ZIP codes. The report broke down home prices by school zone. No hidden agenda here, as the information is available to anyone with access to the Multiple Listing Service; providing this information is a common practice of real estate firms to help potential sellers time the market.

The report was eye opening, nevertheless. The eight schools it included were in areas with median home prices ranging from $805,455 to $2.37 million. Based on data collected by the Florida Department of Education, these schools had – surprise! – “A” grades from the state for the past three years.

All the schools have white student populations of 60% or higher. The school with the highest percentage of students classified as “economically disadvantaged,” Wilson Middle School, reported 28%, while the lowest, Mabry Elementary School, reported 8.7% as meeting those criteria.

This 1,486-square-foot home, located in the F-rated Kimbrell Elementary School zone, is listed for sale at $230,000.

Compare that with F-rated Kimbrell Elementary School, which is one Hillsborough County’s 39 low-performing schools. Department of Education data show just 10.3% of Kimbrell’s students are white and nearly 95% are classified as economically disadvantaged. More than 6% are homeless. What’s more, the school attracts only 48% of its neighborhood children. The rest attend district-run charter schools, a magnet school, or some other form of education choice.

Jason Bedrick, director of policy for EdChoice, a national nonprofit organization devoted to advocating for education choice, is on the record as saying, “There’s no such thing as a ‘public’ school.” Bedrick wrote about this in an essay for the Cato Institute in which he debunked an oft-cited claim education choice critics use while trying to thwart establishment or expansion of choice programs: Private schools get to pick and choose their students, but public schools must take everyone.

Public schools, he wrote, “are more appropriately termed ‘district schools’ because they serve residents of a particular district, not the public at large. Privately owned shopping malls are more ‘public’ than district schools.”

Bedrick argued this wouldn’t be a problem if every school was of the same high quality, but sadly, that is not the case.

Not all families live in a state with access to education choice. Bedrick and Lindsey Burke, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, told the story of a Washington, D.C., couple, both law enforcement officers, who lied about where they lived so their three children could attend higher quality district schools.

Though the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program, established in 2003, has offered relief to the area’s poorest families, Bedrick and Burke wrote that education savings accounts – accounts parents can use to purchase a wide variety of educational products and services using a portion of the public funding that would have been spent on their child at his or her assigned district school – is a model that allows parents to completely customize their child’s education plan to ensure the best fit.

Eight states, including Florida, have established ESAs, though some, including Florida’s, are available only for students with certain special needs.

Universal ESAs would allow students currently zoned for F-rated Kimbrell Elementary the opportunity to attend a school with a state-designated letter grade closer to those of the south Tampa schools featured in the real estate report, as well as access to tutoring or enrichment programs now available only to families who can afford to pay for them.

Our house is now worth nearly triple what we paid in 1997. The fact that the nearby district schools are consistently A-rated no doubt has contributed to the steady climb in home values. Yet surrounded by A-rated schools, we sent our son to a private kindergarten on a state scholarship, and later to other high-performing district schools outside our zone, because those environments were the best fit for him – and because we could afford transportation.

If only everyone had those options, regardless of their ZIP code.

This is the website image that greets families of Saint Francis Academy in Bally, Pennsylvania, with the closure of the 277-year-old school.

A new report from the Cato Institute finds that no fewer than 132 private schools have announced permanent closure over the past year, at least partially due to economic effects of the pandemic. Additional findings indicate private school enrollment has dropped as much as 5% overall.

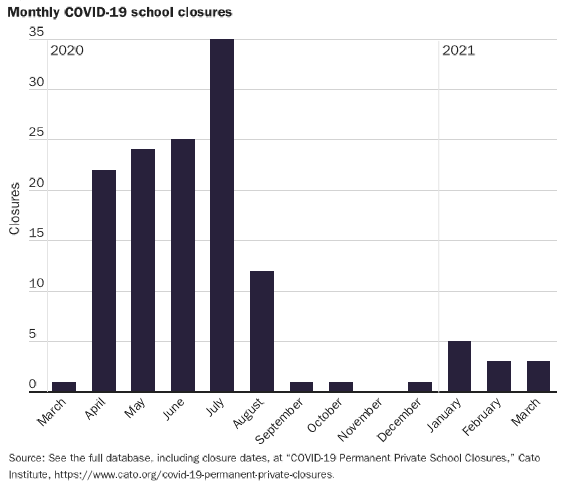

Cato’s COVID-19 Permanent Private School Closures tracker shows closures struck hardest at the beginning of the pandemic and climbed steadily each month from April through July, when closures peaked at 35. The hardest hit sector appears to be schools that are disproportionately low-cost.

The data show the pandemic impacted schools as young as five years old but also claimed 277-year-old Saint Francis Academy in Bally, Pennsylvania, which was founded in 1743. Only the school’s early-education program remains.

The data show the pandemic impacted schools as young as five years old but also claimed 277-year-old Saint Francis Academy in Bally, Pennsylvania, which was founded in 1743. Only the school’s early-education program remains.

Of shuttered schools, most were Roman Catholic (84%), and most were in the Northeast (66%).

The average tuition at the closed private schools was just $7,066, less than half the cost of the average per pupil spending in American public schools ($14,891). Closed private school tuition was also significantly cheaper than the national average private school tuition of $11,173.

Income data for families sending students to these private school was not available, but Cato used Census data as a proxy.

According to Cato, the median household income for families living near pandemic closed private schools was $89,953, close to the overall national median household income of $88,149.

Private schools that closed were more likely to serve Black or Hispanic students than private schools that remained open throughout the pandemic.

Also noteworthy: 111 of the 132 closed schools already had experienced financial difficulty prior to the pandemic.

Despite the uneven financial playing field between tuition-charging private schools and “free” public schools, private school closures have been lower than expected. Government aid may have been one reason why.

According to Cato, the Paycheck Protection Program made an estimated $4.5 billion in forgivable loans available to private schools. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided an estimated $715 million in “equitable services” provided by local school districts paid for by federal grants.

The Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act and American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) will provide another $2.75 billion each in aid to non-public schools. Both programs give priority funding to private schools serving low-income students.

The total aid to private schools will amount to about $2,500 per pupil. Despite this aid, public schools’ financial advantage has grown even larger. According to Cato, public schools will receive an estimated $3,900 per pupil, 56% more than what private schools will receive.

The aid, however, helped private schools remain open for in-person learning, something the Cato report believes reduced the expected enrollment losses as parents shopped for learning options.

The report concludes by celebrating the rise in voucher, tax credit and education savings account legislation, “which would move states closer to a level playing field.”

This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first published on the RealClear Policy blog.

This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first published on the RealClear Policy blog.

A new Gallup poll that surveyed parents with school-aged kids has startling results, much more because of how opinions are split than the opinions themselves.

Given the COVID-19 threat, 36% of parents want their children to receive fully in-person education, 36% want an in-person/distance hybrid, and 28% want all distance. Each mode was preferred by essentially one-third of parents, neatly capturing a now undeniable reality: Families need school choice.

The basic problem is that diverse people have different needs, but a school district is unitary. This is always trouble — diverse people are stuck with one dress code, history curriculum, etc. — but COVID-19 makes the stakes far higher and more immediate than usual. You might be willing to engage in a protracted school board battle to improve curricula, but COVID-19 could put your child’s life, or basic education, in potentially huge danger right now.

In many places, the public schools have taken the side of maximum COVID caution. The school districts in Los Angeles, Chicago, and elsewhere will, at least to start the year, only offer distance education.

That may be fine for kids who learn better at home, have medical conditions that make them high-risk, or who live with elderly relatives. But it is a huge hit to children with poor internet connectivity, learning disabilities, or those who simply thrive in a physical classroom.

It appears that a spontaneous, nationwide eruption of parent-driven, in-person education is the response to such closings. The “pod” phenomenon is perhaps the most buzzy sign of this, generating both fascinated and skeptical coverage in major media outlets. Basically, parents are pooling their money to hire teachers and create closed learning communities for their kids.

We may also be seeing more families moving to traditional private schools, with reports of privates receiving increased interest, and sometimes definite enrollment boosts, around the country. There is no systematic data to confirm a national movement, but the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom has been tracking private school closures connected to COVID-19 since March and has only recorded eight since July 14. This low number may well reflect new enrollments in private schools.

Of course, affording a private alternative can be difficult for lower-income families, and many people worry that the move to private schooling will fuel greater inequality.

Thankfully, there is a solution, and it is straightforward: Instead of education funding going directly to public schools, let it follow children, whether to a pod, private school, charter school, or traditional public. With public school spending exceeding $15,000 per student, most privates, which charge roughly $12,000 on average, would be in anyone’s reach, while families pooling 10 kids could offer $150,000 to a pod teacher.

The Trump administration has been pushing choice, and certainly any federal aid should follow kids. But constitutional authority over education lies with the states, and it is from them that choice should come. Indeed, more than half-a-million children already attend private schools through voucher, tax credit, and education savings account programs in 29 states and Washington, D.C. But that is far below the number who need choice — states that already have it should expand it, and those without it should enact it.

But expanding funding may not be enough to supply the COVID choice people need. In some places, including much of California, public authorities are forbidding many private institutions from teaching in-person. Such prohibitions must be lifted.

These actions may be intended to protect public schools’ pocketbooks. For instance, the chief health official in Montgomery County, Maryland, has said no private school can open until at least October 1, a date right after the enrollment “count day” that determines how much state and federal funding public schools get.

Of course, health concerns may be the only driver of such decisions. But school-aged children appear to face very low levels of COVID danger. According to CDC data, Americans ages 5 to 17 account for fewer than 0.1% of all COVID-19 deaths, and since tracking began, it has accounted for less than 1% of all deaths in the 5-to-14 age group. While increasing safety measures is important, kids appear to face greater dangers than COVID-19.

What about teachers and administrators? Adults are at greater risk than children, but private schools will do many things to protect them, including mandatory mask wearing, face shields, social distancing, improved air filtration, and more. And teachers unwilling or unable to work in-person could choose jobs in online-only schools.

The simple fact is all communities, families, and children are different, and they need educational options reflective of that diversity.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first appeared on InsideSources.com.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first appeared on InsideSources.com.

I do not have any expertise in COVID-19. From what I can tell, I am reflective of the vast majority of people, and hence we are all facing a time of significant uncertainty.

What I do know is that in the face of uncertainty it is good to have diverse options. Just as you want a diversified portfolio of investments because you will be ruined if you put all of your money in one thing and it tanks, when you are not sure what will work you want several possible solutions to exist.

The good news for American education is that it is decentralized, and diverse options exist.

Within public schooling, local control means that districts can respond to their unique local situations. Schools all over the Seattle area can close while Albuquerque’s stay open, and schools can try lots of measures short of lengthy closure to mitigate the coronavirus threat. Of course, local districts face a lot of state and federal mandates, especially about annual testing and related accountability mechanisms, and how those will be handled is stickier.

Perhaps more important than decentralization of government schools is that our charter, private, and homeschooling sectors—and even some traditional districts—have been able to be incubators of sometimes very different ways of delivering education. We may well need to tap into these new mechanisms at greater scale if brick‐and‐mortar schooling is substantially disrupted. This will certainly mean more schooling occurring in homes, perhaps controlled entirely by parents. It will very likely mean more online content delivery as traditional public schools try to quickly transition from in‐person to electronic teaching. The latter will not be easy, but thanks to our having embraced at least modest diversity in education there are already online models operating at scale to provide some blueprint

For some families, a major disruption may even mean discovering the possibility of “unschooling” — letting kids largely steer their own educational paths, with parents only assisting and facilitating. There is experience with that to draw on, too. Indeed, Cato adjunct scholar Kerry McDonald has been especially prominent in disseminating information about unschooling, and she co‐founded a website where you can find lots of unschooling options.

COVID-19 is uncharted territory, and nothing will make it painless to cope with. But at least in education, local autonomy, and having allowed many models to proliferate, lays some good groundwork to respond.

"The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth" by Jennie A. Brownscombe (1914) presents a typical mythologized scene showing Plymouth settlers celebrating Thanksgiving with Wampanoags, dressed in the garb of Plains Indians.

Editor’s note: redefinED is offering this Thanksgiving Day commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, via a Creative Commons republication agreement.

If you know your United States history, you know that the Pilgrims came to North America seeking to practice their religion free from the constraints of the Church of England. If you know your U.S. history well, you know that what many call the beginning of public schooling was the Massachusetts Bay colony’s law of 1647 requiring towns to supply some form of education, lest children fall victim to “that old deluder, Satan.” And if you know your history really well, you know that as public schooling developed it was repeatedly beset by religious conflicts, first as the schools were de facto Protestant, then as they became de facto agnostic.

What am I thankful for this Thanksgiving? That we may be on the verge of tearing down barriers to people directing education funds to schools sharing their religious values, barriers that do not just hurt religious families, but by forcing all to support one system of schools also keep non-religious families from getting what they want. Where religious people are sufficiently numerous, they can sometimes create de facto religious public schools, and where they are not sufficiently numerous to exert outright control educators will often avoid things that upset them.

The barriers I’m speaking of are Blaine Amendments, named after 19th century U.S. Senator James G. Blaine but found in 37 state constitutions. They are being challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue. The case involves a scholarship tax credit program that was struck down by Montana’s supreme court because it would have allowed scholarships to be used at religious schools. Oral arguments are scheduled for January 22, 2020.

These amendments, originally created to keep money in de facto Protestant public schools and out of Catholic institutions, are often interpreted to mean that no government money may go to religious schools even if directed by the free choice of parents. Basically—and as these Cato amicus briefs lay out in greater depth—they force religious people to pay for government schools that legally cannot teach religious beliefs as true, or make policies based on religious convictions. Indeed, the schools often teach things and institute policies that contradict people’s religious beliefs. That violates religious freedom and renders religious people unequal under the law.

The prospects for these amendments being struck down, or at least sufficiently curbed that people can get tax credits for funding religious school scholarships, are good. From Zelman v. Simmons Harris, in which the U.S. Supreme Court established that parents can take state vouchers to religious schools without violating the U.S. Constitution, to the Trinity Lutheran decision that states cannot bar institutions from participating in funding programs simply because they are religious, precedent is on freedom’s side.

For this we should all be thankful. Because more freedom is what America is supposed to be about.

In a PBS documentary, Andrew Coulson asks why education is so different from other industries — like shipbuilding.

In a new PBS mini-series, a leading libertarian embarks on a worldwide quest in search of functioning markets in education.

Spoiler alert: He doesn't find many.

But the late Cato Institute scholar Andrew Coulson does find cause for optimism in his swan song, School Inc., as he scans the globe for places where the best schools are free to grow and serve more students.

He examines America's elite private prep schools, which "have the quality, demand, technology and time to grow into national networks. They just don't." Why? They're more interested in maintaining traditions than scaling up.

He looks at top charter school networks, which are built with scale in mind. But he finds philanthropists don't consistently back the best. "There's a lot of scaling up in the charter sector," he says. "But it's indiscriminate."

He heads to South Korea, where extracurricular hagwons turn the best teachers into big-time entrepreneurs, but notes with concern that this marketplace is fueled, in part, by the country's high-pressure, test-driven college entrance system. He marvels at India's flourishing low-cost private schools, but laments the rise of government regulations that have forced many of them out of business. He notes Chile's voucher system and rising achievement scores, but worries school choice has become a target of a Marxist backlash against the legacy of right-wing strongman Augusto Pinochet. (more…)

Louisiana's voucher program is unique. It has more, and more comprehensive, regulations than most private school choice programs. It has fewer schools participating. And it's the first program of its kind to show such strong, negative academic results.

During a Friday forum on school vouchers and regulation hosted by the libertarian Cato Institute, Patrick Wolf, a University of Arkansas researcher who helped author a series of recent studies on private school choice in Louisiana, said there's not yet enough evidence to tell whether the Louisiana Scholarship Program's unique design helps explain the unprecedented finding that it harmed student achievement in its first two years.

Those results renewed a major philosophical debate in school choice circles. Does regulation of private schools that accept vouchers hamstring their performance and keep the best schools from participating? Or can it spur private schools to serve disadvantaged students, and to get substantially better over time?

A number of factors cloud the findings in Louisiana. Its voucher program is fairly new, first expanded statewide during the 2012-13 school year. Some students might have seen their academic performance drop as they adjusted to new schools. Some schools might have needed more time to adjust their curriculum and instruction to the state standardized tests, which voucher students are required to take. There are signs of improvement in Louisiana public schools, which served as a comparison for voucher schools.

But Wolf said those factors together explain less than half of the negative results. Some of the participating private schools may be been low-quality, or unequipped to educate low-income students who use vouchers.

The bad results in year one looked a bit better in year two, and John White, Lousiana's state schools superintendent, has told lawmakers that as the lowest-performing schools face sanctions and others get better at serving disadvantaged students, results will keep improving. He has also issued a challenge to those who criticize his state's approach to regulating school vouchers: Come up with a model for ensuring private schools can serve all students well, at scale. (more…)

Educational choice advocates have urged caution amid early reports that show, so far, Nevada's new, near-universal education savings account program seems to be attracting families who are relatively well-off.

They're right to note these participation numbers reflect the "earliest of the early adopters." It will take time for outreach efforts to inform low-income families about their new options, and to allow a new education marketplace to develop in the Silver State.

But the early participation data, and the debate swirling around it, also show why it's important for the educational choice movement to cultivate support among people, especially those on the political left, who may be skeptical of the market forces ESA backers hope to unleash.

Supporters hope education savings accounts will allow new providers into the education system, while also allowing families to economize, thereby forcing schools to compete on price.

The hope is that market forces will ultimately propel a cycle of innovation that, even if it doesn't draw large numbers of the most disadvantaged families into the program in the early days, will benefit them over time. Jason Bedrick of the Cato Institute notes this is what happened with a number of consumer goods, including smartphones. (more…)

The school choice movement has already set a new high-water mark this year.

The Wall Street Journal labeled 2011 the "year of school choice," after states either created or expanded 13 school choice programs. But 2015 has surpassed that tally, and then some.

Jason Bedrick of the libertarian-leaning Cato Institute has been doggedly keeping track.

As of my last update in early July, there were 17 new or expanded choice programs in 14 states. On Friday, North Carolina lawmakers finally passed a long-overdue budget that expanded the state’s two school voucher programs for low-income and special-needs students, bringing the total number to 19 new or expanded programs in 15 states.