CARES Funding: Just 10 percent of the $693.2 million from the CARES Act funds available to Florida has been allocated to schools. Hillsborough County schools have received $29 million and only 10 other school districts have received more than $1 million in funds to date. Tampa Bay Times.

CARES Funding: Just 10 percent of the $693.2 million from the CARES Act funds available to Florida has been allocated to schools. Hillsborough County schools have received $29 million and only 10 other school districts have received more than $1 million in funds to date. Tampa Bay Times.

Computer programing: Salaries in Florida for computer based occupations double the state average, but only 30 percent of public schools teach courses in the subject. Nearly 400 teachers in Miami-Dade are prepared to complete state certifications to teach computer science. Miami Herald.

Corona caution: Duval County schools superintendent urges students to be take precautions against the coronavirus at school and at home with face coverings, hand washing and social distancing. WJXT.

Effective?: Palm Beach County Schools Superintendent Donald Fennoy was rated "Effective" by the school board. Two board members pushed unsuccessfully to put Fennoy on an "improvement plan." Palm Beach Post.

Pay Raises: Gov. DeSantis and the legislature set aside $500 million for teacher pay raises, including requiring a minimum teacher salary of $47,500, but not all teachers have seen their pay raise yet. While the teacher union accepted the deal in Palm Beach County the union rejected the raise in Broward. Negotiations are ongoing. Sun Sentinel.

Students for Trump: Students marching through Riverview High School during spirit week face a backlash from classmates. WFLA. A New Smyrna Beach high school student is suing his school after his parking pass was revoked. The 18-year old student believes the punishment was due to the red, white and blue elephant, painted with the word "Trump," in the back of his father's pickup truck. WVTV.

STEM: Former Miami Heat star Chris Bosh will become dean of DRL Academy, helping students learn STEM skills through games and online lessons on how to build drone racers and more. DRL Academy is a project of the Drone Racing League. Bradenton Herald.

Teacher survey: What is it like to teach students during the pandemic? A NBC 6 survey finds out. WVTJ.

Quarantine: 70 students and staff at Palm Lake Elementary School will be in quarantine for two weeks while two high schools in Orange County have reopened. Orlando Sentinel.

Alachua: Covid cases are not as widespread as previously feared, though 507 people in the school district have been infected. More than 30,000 students were enrolled in Alachua County last year. Gainesville Sun.

Manatee: Manatee County schools are looking to do another tax referendum in 2021 or 2022. The last property tax referendum passed in 2018 and is set to expire in 2022. Bradenton Herald.

Opinion: John E. Coons, professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley, reflects on the excuses made by opponents of school choice to thwart educational opportunities for low-income students over the past 50 years. redefinED.

As the first full year of schooling during the coronavirus pandemic launches, a national education advocacy network is sounding the alarm in a research brief that America’s K-12 education system is in crisis.

As the first full year of schooling during the coronavirus pandemic launches, a national education advocacy network is sounding the alarm in a research brief that America’s K-12 education system is in crisis.

To ensure a more flexible, equitable and student-centered system of education both now and post-pandemic, the independent non-profit organization 50CAN is calling for a national response to that crisis, starting with a greater level of federal support for new learning modes to extend greater choice for families, including distance learning, homeschooling, and micro-schools and learning pods.

While schooling traditionally has been funded through a mix of local property taxes and state revenue with the federal government paying only about 10% of total costs, 50CAN observes, a greater level of federal support across these three modes of learning is needed.

Among 50CAN’s overall policy recommendations:

· All district, charter and private schools should receive emergency funding to support safely running in-person schooling this school year if they are able to do so and to provide a flexible, high-quality online schooling option for all students.

· Families should be able to easily move into or out of these in-person and online options as their health circumstances and risk factors change throughout the year.

· Families should have the option to enroll their student in an online district school program outside of their neighborhood boundaries or in an online charter school or private school program anywhere in the country with no restrictions to these online transfers, such as state enrollment caps.

· Families should receive funding to enroll their child in an in-person school in a neighboring district or in a charter school or private school if their district school does not offer an in-person option.

· Families up to 200% of the poverty line should receive a direct payment of $2,000 per child to pay for supplemental educational materials, tutoring, technology and other learning expenses, building upon payments -- $1,200 per adult and $500 per child – in the CARES Act.

The independent non-profit organization, launched in 2011, has a presence in eight states with affiliates in additional cities including Miami.

South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster announced in July the allocation of $32 million from the Governor's Emergency Education Relief (GEER) fund to create one-time grants to help parents pay tuition for their children at the state's private schools.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Katherine Kellett Bathgate, a senior policy adviser for State Policy Network and CEO and co-founder of SchoolForward, first appeared on The 74.

The American Federation of Teachers recently made headlines when it passed a resolution expressing support for any chapter that wishes to strike over schools reopening. Since then, there have been increased rumblings about possible strikes in several states.

I sympathize with teachers who are afraid to return to work, especially those who are not using the threat of strikes to achieve political goals, as some unions have done. I feel for school administrators having to make tough decisions about student and staff safety.

But if schools don’t reopen, whether because of a strike or a state or district decision, the taxpayer money that funds those schools should go to the impacted students and families.

A recent nationwide poll of 1,000 parents of K-12 children commissioned by State Policy Network showed that in the spring, during school shutdowns, families spent on average $200 total and 10 hours a week supporting their children’s education. It also revealed that 40% of parents believe their children are behind academically because of those school closures.

America cannot afford to have children fall further behind as we ride out this pandemic, and families can’t afford to continue subsidizing their children’s education like they did this spring.

Districts are announcing new closures and delayed starts every day, and parents are still grappling with whether they feel safe sending their kids back to their schools (the same poll showed only one-third to be comfortable under current conditions). As a result, some parents have turned to ideas like learning pods, where a handful of families team up to hire a teacher together or share the responsibility of homeschooling.

As this entrepreneurial idea has taken hold, and as mom Facebook groups are exploding with ideas about pods and requests to join, some have rightly questioned how equitable this is. What happens to students whose parents don’t have the financial means to hire a teacher? Or who have working parents who can’t help homeschool?

The answer has been around for nearly 10 years. It’s been tested and implemented, and all we need to do is act.

Education savings accounts, first passed in Arizona in 2011, allow families to spend a portion of their child’s state education funding on qualifying education expenses. This could be used for homeschooling, online tutoring or even chipping in to hire a teacher for a neighborhood learning pod.

Support for this idea is high, with 63% of parents in the poll saying they support passing “emergency” or “pandemic” ESAs and 35% saying they would be very or extremely likely to use a program like this if available in their state.

The challenge will be how to make ESAs a reality fast enough for families. Historically, states have taken a year or more to implement these programs once they’re passed into law. Families don’t have that kind of time right now.

But there are other ways. One example is using CARES Act funding. In South Carolina, Gov. Henry McMaster recently announced a $32 million SAFE Grants program to give low-income families up to $6,500 to fund their child’s education. As every governor has discretion to use education funds under the CARES Act, there’s no reason other states could not follow suit and direct this money to families as an ESA instead of a grant program.

States could also use special sessions to pass one-time emergency or pandemic ESAs to give a portion of each student’s funding back to the families.

Every parent of school-age children in the country has tough decisions to make as we head into the fall. As a working mom with two kids and another on the way, I empathize greatly with what parents are going through right now. We must adjust public policy to meet these needs and lighten the burden families are facing.

Now is the time to be bold and act quickly, lest we lose another year of education for millions of students.

And as someone who works in education policy, I know that we cannot afford to lose another year — or even a half year — with our children’s learning. Achievement gaps will widen further and too many kids will fall behind, especially in low-income and underserved areas. Every family, regardless of their means, should have the ability to choose the education path that is right for their child, especially this year.

So, teachers unions: Go ahead and strike. School districts: Go ahead and decide not to open. You may have legitimate health reasons for doing so. But don’t be surprised when there’s a groundswell of parents asking for their money back.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwalbach, a research assistant at The Heritage Foundation, first published on The Daily Signal.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwalbach, a research assistant at The Heritage Foundation, first published on The Daily Signal.

When COVID-19 brought the school year to an abrupt halt early this year, few anticipated that the global pandemic would be the impetus for private school choice reforms across the nation.

As is the case with so many other sectors, many private schools struggled after losing tuition and other funding resources due to the strains of COVID-19.

In fact, the Cato Institute reported that as of this month, 115 private schools had announced permanent closures.

That means that more than 15,400 children lost their schools. The estimated transfer cost of these students to public schools is more than $278.3 million.

Recognizing what the loss of education options would mean for families, policymakers in six states proposed emergency private school scholarships in response to the crisis. Four of those states—Florida, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Carolina—used emergency federal funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to expand private school choice options.

The CARES Act, signed into law by Donald Trump in June, authorized $3 billion for the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund, or GEER, a flexible grant that governors can use for education-related programs.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, used a portion of his state’s GEER funds to craft “Stay in School” scholarships, providing $10 million to cover tuition at Oklahoma’s 150 private schools for children from low-income families whose incomes have been affected by the coronavirus pandemic. More than 1,500 Oklahoma children could receive a scholarship worth $6,500 each.

That covers all or most of the average annual cost of private school tuition in Oklahoma, which is about $5,000 for elementary students and about $7,000 for secondary students. The scholarship amount, however, is still less than the average per-pupil amount, $8,778, spent annually by Oklahoma public schools.

Oklahoma students also will have access to the $8 million Bridge the Gap Digital Wallet education savings account-style funding, which is funded by GEER and will provide more than 5,000 children living in poverty with $1,500 grants to “purchase curriculum content, tutoring services and/or technology.”

In the era of pandemic pods, this is critical policy.

Likewise, South Carolina used its GEER funds to create a private school scholarship program for children from low- and middle-income families. Children living at or below 300% of the federal poverty line could be awarded a scholarship of about $6,500.

Other states used these funds to bolster existing private school choice programs such as tax credit scholarships.

New Hampshire under Gov. Chris Sununu, a Republican, boosted funding for the state’s tax credit scholarship by $1.5 million. The state’s tax credit scholarship allows individuals and businesses to receive tax credits for donating to nonprofits that fund private school scholarships.

Since 2015, New Hampshire’s tax credit scholarship has allocated $3.8 million to help 1,377 children attend private schools of their choice. The additional emergency funds will help 800 children receive scholarships valued at $1,875 each. That amount covers more than 22% of the average cost of tuition at a private elementary school in the state.

Like New Hampshire, Florida used $30 million of its GEER funds to stabilize its tax credit scholarship. At the same time, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, also put $15 million toward the Private School Stabilization Grant Fund. Private schools are eligible for this grant if they were hard hit by the pandemic and if more than 50% of the student body uses school choice scholarships.

Never missing a beat, special interest groups have alleged that efforts in those states to use GEER funds to support families accessing education options of choice will hurt public schools. Yet, public schools in Florida, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Carolina received a combined $1.1 billion from the CARES Act. Of that, the total governors’ discretionary funds accessible to children enrolled in private schools in the respective states totaled $96.5 million.

Taxpayers and state policymakers are right to balk at the new federal education funding. The $13.5 billion CARES Act, along with the $3 billion in GEER funding, is significant new federal spending, representing more than 25% of what the federal government spends yearly on K-12 education through the Department of Education’s discretionary budget.

But as The Heritage Foundation’s Jonathan Butcher wrote: “If the funds already are appropriated for education, as it is with CARES spending, then there is no more effective purpose than to give every child a chance at the American dream with more learning options.”

Moving forward, state policymakers should make sure that the emergency private school scholarships become permanent, funding them through changes to state policy. Rethinking how education funding is delivered, through more nimble models such as education savings accounts, should remain a permanent feature of the education policy landscape.

Moves in these states are steps in the right direction.

The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on Aug. 6 held a public hearing on “Challenges to Safely Reopening American Schools,” featuring former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan; Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Broward County (Florida) Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie; and Angela Skillings, a second-grade teacher in the Hayden-Winkelman Unified School District in Arizona. You can see their prepared testimony here, here, here and here. redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity, also participated. The following is Lips’ condensed spoken testimony.

The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis on Aug. 6 held a public hearing on “Challenges to Safely Reopening American Schools,” featuring former U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan; Caitlin Rivers, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security; Broward County (Florida) Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie; and Angela Skillings, a second-grade teacher in the Hayden-Winkelman Unified School District in Arizona. You can see their prepared testimony here, here, here and here. redefinED guest blogger Dan Lips, a visiting fellow with the Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity, also participated. The following is Lips’ condensed spoken testimony.

As we have heard today, communities across the country are facing a difficult decision about how to begin the school year during the pandemic. The prospect of any child, teacher, or school employee contracting COVID-19 and facing the possibility of death or serious illness should weigh heavily on all policymakers involved with decisions affecting schools’ plans.

But it is critical that policymakers also recognize the serious risks associated with prolonged school closures, particularly for disadvantaged children.

Researchers studying the educational effects of school closures warn that time out of school results in months of lost learning, and that the learning losses are most acute for low-income students.

The bottom line is that prolonged school closures will create a large achievement gap for a generation of American children. Beyond these educational effects, prolonged school closures create significant risks for children’s health and welfare.

There is alarming evidence, which I describe in my written testimony, that prolonged school closures since the spring have endangered child welfare. Closures also have significant negative economic effects for parents. Many parents have been forced to choose between their jobs and their child’s care, and this challenge is most difficult for single parents.

The good news is that it is possible for schools to reopen.

Health experts — including the American Academy of Pediatrics — have issued guidelines for safely reopening schools with certain precautions, such as physical distancing, utilizing outdoor space, cohort classes to minimize crossover among children and adults, and face coverings for students (particularly older students).

And we are seeing many school districts choose to reopen across the country with in-person instruction or hybrid learning options.

According to a new analysis from the Center for Reinventing Public Education, 41 percent of rural districts and 28 percent of suburban districts plan to provide in-person instruction this fall. But most the nation’s largest school districts are not reopening with in-person instruction.

Seventy-one of the nation’s 120 largest school districts are beginning the school year with remote instruction and no in-person learning, based on FREOPP’s review. Altogether, these closed school districts serve more than 7 million children — including 1.4 million children living in poverty.

It is important to recognize that children from low-income families have fewer resources to learn outside of school than their peers. According to one estimate, rich families spend more than $9,000 out of pocket on their children’s educational and enrichment outside of school, while the poorest families spent just $1,400.

Today, families with financial means are working to create better options than remote learning — including homeschooling and setting up “pandemic learning pods” by forming coops with other parents and hiring teachers or tutors. But children from lower-income families have few options. Policymakers must address this inequality.

For example, states should use existing CARES Act funds to provide aid directly to parents in the form of education savings accounts or scholarships to support their children’s outside of school learning needs. Oklahoma, New Hampshire, and South Carolina are already doing this. Other states should follow their lead.

As Congress considers future aid packages for K-12 education, you should provide aid directly to parents to help disadvantaged children learn when their school is closed. There is precedent for providing emergency education relief in this manner.

After Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita in 2005, many children were displaced and had nowhere to go to school. Congress provided more than $1 billion in aid that followed affected children to a school of their parents’ choice, allowing them to continue their education.

If millions of children are unable to attend school this year, Congress should focus much of its aid in a similar manner — providing direct assistance to help children continue learning while schools are closed. In my written testimony, I discuss these and other recommendations for how school systems can prioritize and address the needs of disadvantaged children during the pandemic.

Since 1965, Congress has rightly focused federal education aid on promoting equal opportunity for at-risk children. In 2020, this will require focusing aid to support disadvantaged kids who can’t go to school.

The Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity will host an executive briefing on its recommendations for reopening and continuing American education during the pandemic on Thursday. Visit https://freopp.org/ for details.

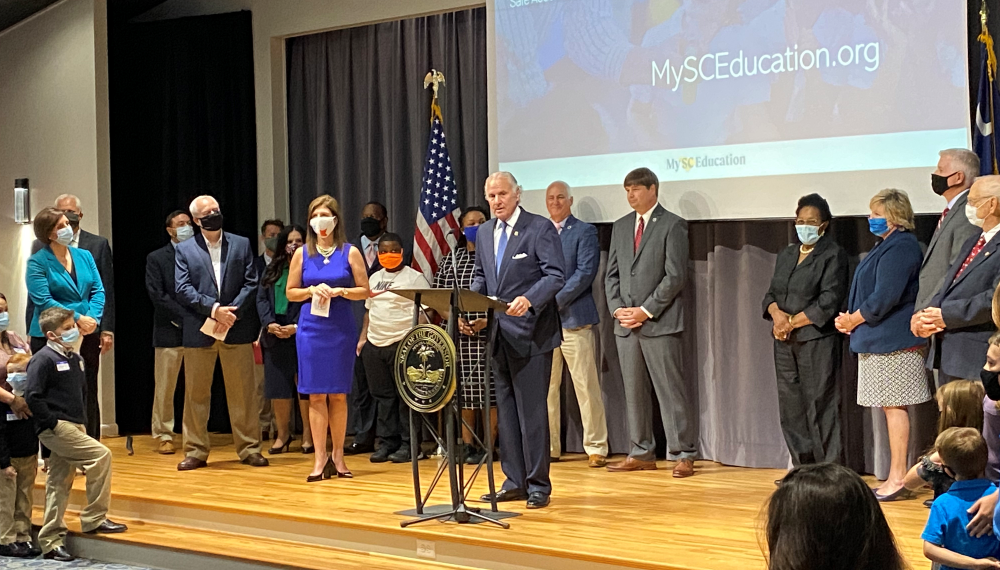

South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster announced Monday that he will use $32 million in education relief funds for school choice grants.

The COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in months of uncertainty for families with children in K-12 schools, but South Carolina officials on Monday made one thing clear: The state’s families will have more options this academic year.

Gov. Henry McMaster, a Republican, announced creation of a private school scholarship program for students from low- and middle-income families. Children from families at or below 300% of the federal poverty line will be eligible for scholarships worth up to $6,500.

The scholarships come at an auspicious time because large districts in neighboring states are refusing to offer in-person learning—Atlanta to the south, Nashville to the west—while some school districts in-state have not announced their plans.

Parents wondering what another semester of on-again, off-again virtual delivery of lessons will mean for their students should brighten at the prospect of new choices.

There has been no shortage of questions before parents during the spring: Can I work with my children at home? Should I homeschool in the fall? Did my child learn anything this spring?

The answers vary by family, but surveys have demonstrated the responses to be “kind of,” “maybe,” and “ask again later,” in that order.

Surveys find more families are considering homeschooling in the wake of the coronavirus, but this option is a challenge for dual-income households or single working parents. Meanwhile, research estimates that students may have lost approximately 30% to 50% of any gains they made due to the interruption of the last school year.

McMaster is using part of federal K-12 spending from the CARES Act, legislation passed earlier this year that provided funds to states for health care, education, and other social and policy areas affected by the pandemic. The portion McMaster chose was a fund specifically under the directive of the governor’s office. Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt made a similar move last week.

Bureaucracy and the potential for increased state dependency follows federal spending, so stimulus money should make any taxpayer or state policymaker blanch. But if the funds already are appropriated for education, as it is with CARES spending, then there is no more effective purpose than to give every child a chance at the American dream with more learning options.

“Education is the most important thing we do in South Carolina, or anywhere else,” McMaster said. “We must find a way to give [children] the best education, understanding, the best preparation for the future that we possibly can.”

Should interest groups such as unions or school board and superintendent associations argue for more spending on traditional schools, policymakers can remind them that the federal government provided a much larger portion–$13.2 billion—to K-12 schools through state departments of education; just $3 billion was set aside for governors such as McMaster to use.

Meanwhile, the myths about federal spending on K-12 schools are resilient. Last week, “The View” co-host Joy Behar actually said that Washington has cut spending on schools in recent years.

This claim is so demonstrably false that it is nearly embarrassing to correct, but why not: After adjusting for inflation, total per-student spending stands at more than $15,400 today, the highest figure in American history and approximately double the amount spent per child in the 1970s. Yet teacher unions and other special interests are calling for “at least” another $250 billion in federal spending for schools.

Shortly after unions issued this demand, the Government Accountability Office released a report demonstrating that schools had spent a small fraction of the federal money already issued to them in March to deal with the pandemic.

News coverage of the report indicated that some school officials were waiting to see how much else they would receive from Congress before spending the already-approved money. These delays hardly make the need for new spending feel urgent.

Thus, it is all the more significant that McMaster decided to allow spending already appropriated and under his supervision to follow students. The governor said South Carolina needs to “give parents confidence” about education this fall.

The scholarships are “your tax money, coming back,” he said.

South Carolina’s scholarships will allow families to decide now where their child will learn in the fall, restoring confidence for parents over their student’s learning experience. Considering the ongoing speculation about schools, confidence is a good sentiment for state policymakers to spread around.

Kindergartner Sofia Ascencio wears her graduation gown to a farewell parade at St. John the Baptist Catholic School in Napa, which is closing after 108 years due to declining enrollment and the coronavirus pandemic.

We can always use more examples of teamwork. Public-school officials have such an opportunity before them as schools prepare to re-open and should to seize it – and resist calls to resort to turf warfare.

In March, Washington provided additional resources through the CARES Act so that school districts can help their schools and private schools with COVID-19-related needs. Federal officials began distributing the money just as some public-school officials objected to federal guidance on how school administrators were to use the spending.

Before taking sides, an honest—perhaps generous, in some places—assessment of school district activities during the pandemic is that school responses across the U.S. were uneven. When school buildings closed, some public officials either waited weeks to deliver any instruction to students quarantined at home or failed to do so at all. Those who observers say responded quickly, such as the ones in Miami-Dade and charter schools in low income areas in Philadelphia and Arizona, deserve credit, but by the middle of May, reports indicated that more than two-dozen large districts across the U.S. had made online work meaningless by not grading students.

The lackluster response helps to explain why recent polls have found that 40-60 percent of parents are considering homeschooling this fall. Fear over another outbreak after students are back in close quarters may also be on parents’ minds, but school districts that failed to follow through during the pandemic has some parents wondering if they could do better themselves.

School districts have another chance to earn the confidence of families, though. In April, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said that districts should use CARES spending to provide services to private schools based on a private school’s total enrollment, not just the number of students in need attending private schools.

Things get technical quickly with this provision, but the usual suspects in unions ignored the details and said districts should ignore the guidance, claiming “this funnels more money to private schools.”

In reality, the main federal education law, now called the Every Student Succeeds Act, says that low-performing private school students in low-income areas can get help from public schools. This part of the law, called “equitable services,” includes tutoring and summer school. Private school officials must work with public school leaders to determine how the help will be delivered.

With the new COVID-19 spending, the Education Department said that equitable services should help all students—public and private—not just struggling students. Why? Because CARES Act money is emergency spending, not annual spending for students in low income areas.

Just as with the delivery of traditional equitable services, private school leaders and students will make these plans with local district schools—giving traditional schools the chance to show private school families that public schools can help them.

Districts have another reason to make the most of equitable services now: As groups such as Ed Choice have explained, if private schools close, taxpayers could see K-12 costs increase during the recession.

We are still plumbing the depths of a financial crisis, and smart districts are already cutting costs to prepare for next year. Larger classes at a time of limited services will not appeal to parents.

Indiana and Maine have said they will not abide by the guidance. Private schools in Pennsylvania and Colorado are challenging their state agencies’ interpretations, which are also limiting access for private school students.

Meanwhile, South Carolina Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman said the state will follow the federal guidance. In a letter to private school educators, she said, “Public and private school leaders working together can address the true needs of South Carolina’s education system caused by COVID-19.” Florida officials have said they will also follow the department’s interpretation. Secretary DeVos said her office is working on an official rule.

Public schools should not view equitable services during the pandemic as a new front in some perceived brawl. All students and schools need help now, so public schools have a chance to be the hero. Perhaps district actions in good faith here could be used to sway public opinion during a recession should districts try to appeal to state taxpayers for more resources.

But if not, and should districts leave private schools to wither, expect more polls showing parents are ready to keep students home—even if private schools close.

Explain that to taxpayers.