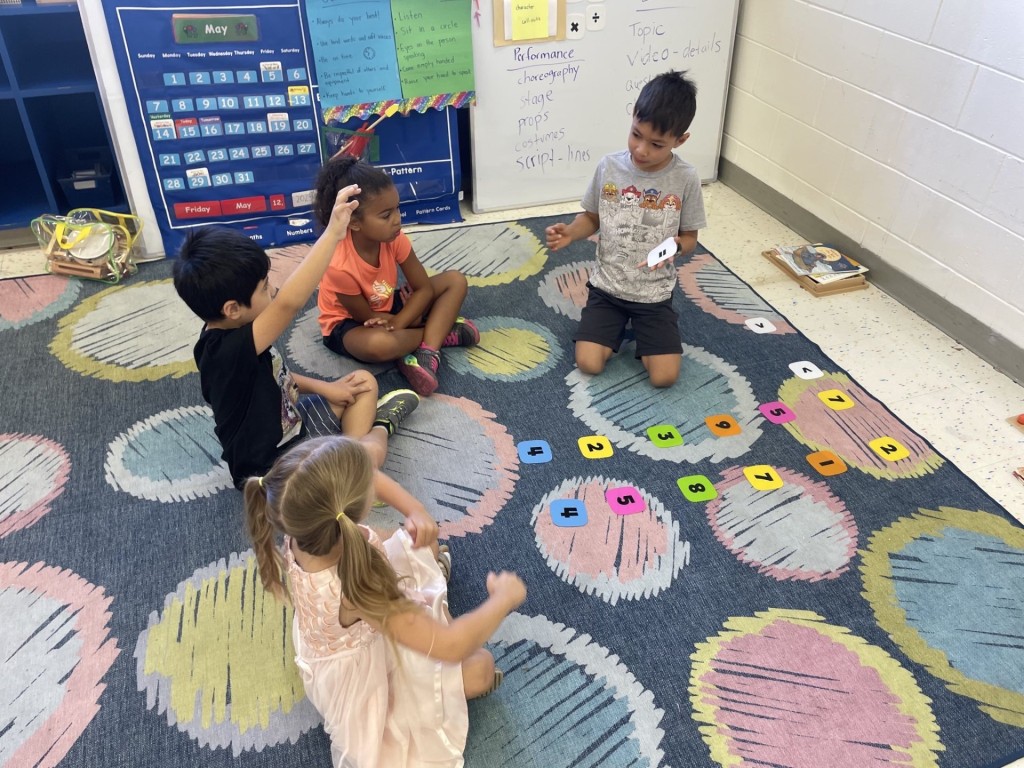

Students at Apollo Academy, a Tampa-based affiliate of Acton Academy, help each other with math. The Acton model emphasizes. student-led learning and includes 270 schools worldwide. Photo courtesy of Apollo Academy

When Apollo Academy opened in Tampa last year, 20 students showed up to participate in the inaugural year of student-led learning.

By the time the Tampa-based school closed for summer break, half that number remained. Some families moved away, while others dropped out of the program.

“We ended up with 10 very happy learners,” said founder Beth Ann Valavanis, an executive who left the corporate world to start Apollo, an Acton Academy affiliate, after a search for future schooling options for her preschool daughter left her unsatisfied. “When we started it was about creating an environment for joyful, happy, lifelong learners, and I feel we did that.”

Valavanis has every reason to call her first year a success. Schools in the Acton Academy network and other small learner-driven schools aren’t the best fit for everyone. Even for those who eventually thrive in that environment, there is an adjustment period, especially for parents who aren’t accustomed to independent learning and the lack of traditional metrics to gauge progress.

A former public school teacher who founded an Acton affiliate in Nevada described it as a “detox.”

“All of that is true,” Valavanis said. “There is a shock at the beginning, and that transition takes longer than we realized it would. Parents were saying, ‘We’re not getting worksheets. We’re not getting graded tests.’”

Students from traditional schools, who were not used to being able to make a move without raising their hand for permission, suddenly were free to take a restroom break or quell their hunger pangs with a snack. Valavanis and her guides told the kids: “You know your body better than we do.”

After five or six weeks, as families adjust to the new model, which trades homework and traditional grades for self-paced, competency-based learning, things change.

“Now we can’t imagine school not being like this,” Valavanis said.

Like other Acton schools, Apollo embraced project-based learning and the Socratic method, in which adults eschew directives in favor of guiding students with questions that help them form their own ideas. Students who felt stressed could visit the calming corner. Students involved in conflicts could visit a friendship tent to work out disagreements. On Fridays, “character callouts” offered an opportunity for students to publicly praise classmates for displays of hard work or positive behaviors they had observed during the week.

Apollo Academy founder Beth Anne Valavanis

Valavanis discovered Acton Academy, a network of small private schools that promotes education as an adventure in autonomy, while looking for acceptable options for her daughter, Emilia. Valavanis, who at the time was new to the Tampa Bay area, wasn’t critical of the A-rated neighborhood public school or faith-based private schools. She just wanted something different. During her morning commute to work, she listened to the audiobook “Courage to Grow: How Acton Academy Turns Learning Upside Down” by Laura Sandefer, an educator who founded Acton Academy with her husband, Jeff, a billionaire entrepreneur from Texas.

Acton began in 2009 with the Sandefers’ two sons and five neighborhood kids in a rented house in Austin, Texas. Jeff Sandefer told reimaginED in a 2022 interview that the plan was to have only one school. But one family moved to California and wanted to start Acton there. Another friend from Guatemala saw Acton during a visit and asked to start an affiliate there.

From there, the concept went viral. Today, Acton has 270 affiliates worldwide, including 15 in Florida.

Valavanis’ school operated last year in a local YMCA after issues with the original location forced it to move. This year, Apollo will operate in space leased from Hyde Park Presbyterian Church in South Tampa. The new location will offer a host of amenities, including a creative makerspace, a renovated playground, a shaded parking lot for a basketball hoop, and a co-working space for parents.

Apollo, which accepts the state’s K-12 education choice scholarships, will offer part time services for families using personalized education plans to customize their children’s educations. So far, 30 students have signed up for the program, which serves learners from kindergarten through sixth grade.

Valavanis said they will take lessons learned from the first year and apply them, including devoting more time to the adjustment period, which Acton calls “Building Our Tribe.”

“It’s not like traditional school, where you jump in the first day, and the teacher has to give 540 instructional hours, so they have to start lesson one, chapter one,” Valavanis said. “It’s about discovering yourself and realizing this is a safe place and getting use to not only asking questions but answering other people’s questions.”

Apollo Academy, an Acton affiliate, is a self-described “single-room schoolhouse designed for the 21st century” for students in grades K-5. Opening this fall in Tampa, it will provide a framework and environment that prioritizes mastery of foundational curriculum while offering children the freedom to make their own decisions.

As the COVID-19 pandemic moved into its second year, school got more stressful for Monique Levy’s kids.

Six-year-old Sima could barely remember a time when COVID-19 wasn’t a threat. School safety measures made the girl who loves Sonic the Hedgehog and riding her bike fearful.

“She was quickly losing her love for school,” Levy said, noting that pre-COVID, when Sima was in kindergarten, she would wake on Saturday mornings wanting to join her classmates.

Meanwhile, 9-year-old Emet was anxious too, mostly in the evenings due to a heavy homework load that left him little free time to pursue passions like astronomy and marine life. The private school Sima and Emet attended was nurturing and supportive, but three years of operating in pandemic mode made Levy question whether her children were in the right place.

“It did not feel right to us,” Levy said. “There had to be another way.”

One day, she happened to drive past a “charming little house” with a sign out front that said Apollo Academy. She and her husband immediately arranged a visit to the Tampa school.

“We toured this unique building filled with modern studios for STEM, arts, reading, math, and even a library that just invited you to sit down and read, which Emet did almost immediately,” she said. “After we finished the tour, it was clear this was the place our children needed to be.”

The Levy kids are now among 20 learners from 12 families who will begin what Apollo calls a “hero’s journey” when the new private school opens Aug. 10. The school is accepting the state’s Family Empowerment Scholarship for Educational Options administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

The private school is an affiliate of Acton Academy, a worldwide network of 270 microschools that promotes education as an adventure in autonomy. Founded by billionaire entrepreneur Jeff Sandefer and his wife, educator Laura Sandefer, Acton combines Montessori’s self-directed learning with the Socratic method of responding to questions with questions to inspire independent problem solving.

Acton does not have tests or homework. Students show skill mastery by building portfolios of their work. Failing is seen as a beneficial experience, an opportunity for students to learn at their own pace.

“We’ve seen overwhelming community support,” said Beth Ann Valavanis, who founded the school after being inspired by Laura Sandefer’s book, “Courage to Grow.” At the time, Valavanis was looking for the best learning options for her daughter, Emilia.

“So many people are rooting for us in a really fun way,” she says of Apollo. “We’re so excited with the growth of Tampa and all the families moving here, and we are excited they’ll have an option that’s different from traditional school.”

Valavanis is putting the finishing touches on her renovations, which include a new roof and interior improvements. She also has hired four “extremely dynamic” guides to support students with their learning.

Those guides include Florie Reber, an artist with 30 years of experience in non-traditional settings and the owner of Yellow Bird Art Studio; Kathleen Amirault, an environmental educator and naturalist; Tiarah Bentley, an educator with a background in Montessori learning; and Levy, who holds a master’s degree in special education and elementary education.

Valavanis said the first five weeks will be spent focusing on “Building Our Time” to allow students to get to know each other and learn about their new environment. That could mean unlearning some practices of traditional school.

“You can eat when you’re hungry and go the bathroom when your body tells you to,” she said.

The school also will pose a question of the year. For this inaugural year, the question will be: What is the purpose of school?

“We’re all going to transform ourselves in a new way, together,” Valavanis said.

Sima and Emet are excited to be embarking on a new adventure, Levy said, especially one that does not include traditional tests or homework. As a parent, she’s thrilled that children who attend Acton Academy schools usually advance two to three grade levels in a year, a fact that inspires confidence in the non-traditional model.

“I am very confident that both my children will find their place at Apollo,” Levy said. “I’m so excited to watch them find the courage to grow.”

Acton Academy opened in 2009 with 12 students, teaching content through online game-based tools, Socratic discussion and face-to-face projects the school calls “quests.” Today, Acton offers kits to entrepreneurs and parents interested in opening their own schools following its model.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Michael B. Horn, co-founder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, is included in the Summer 2020 edition of Education Next.

From San Francisco to Austin, Texas, to New York, new forms of schooling termed micro-schools are popping up.

As of yet, there is no common definition that covers all these schools, which vary not only by size and cost but also in their education philosophies and operating models. Think one-room schoolhouse meets blended learning and home schooling meets private schooling.

As Matt Candler, founder of 4.0 Schools, writes:

“What makes a modern micro-school different from a 19th century, one-room schoolhouse is that old-school schools only had a few ways to teach — certainly no software, no tutors, and probably less structure around student to student learning. In a modern micro-school, there are ways to get good data from each of these venues. And the great micro-school of the future will lean on well-designed software to help adults evaluate where each kid is learning.”

Several factors are driving their emergence. Micro-schools are gaining traction among families who are dissatisfied with the quality of public schooling options and cannot afford or do not want to pay for a traditional private-school education. These families want an option other than home schooling that will personalize instruction for their child’s needs. A school in which students attend a couple days a week or a small school with like-minded parents can fit the bill.

Some trace the micro-school’s origins to the United Kingdom, where over the past decade people began applying the term micro-schools to small independent and privately funded schools that met at most two days a week. As in the United States, the impetus for their formation was dissatisfaction with local schooling options. Although home-schooling families have for some time created cooperatives to gain some flexibility for the adults and socialization for the children, the micro-schooling phenomenon is more formal.

One of the early U.S. micro-schools, QuantumCamp, was founded in the winter of 2009 in Berkeley, California, out of a dare that one couldn’t teach quantum physics in a simple way. The result was the development of a course that would be accessible to children as young as 12.

The school now offers a complete hands-on math and science curriculum for students in first through eighth grades and serves about 150 home schoolers during the school year; double that number attend the summer program. Tuition ranges from $600 to $2,400 depending on the program and enrollment period.

In 2013, QuantumCamp introduced language arts courses. Each academic class meets once a week for an activity-based exploration of big ideas and then offers out-of-class content that includes videos, readings, problem sets, podcasts, and other activities to enable students to continue exploring concepts at their own pace.

At roughly the same time as QuantumCamp’s founding, in Austin, Texas, Jeff Sandefer, founder of the nationally acclaimed Acton School of Business and his wife, Laura, who has a master’s degree in education, launched Acton Academy. In creating the five-day-a-week, all-day school, the couple sought to ensure that their own children wouldn’t be “talked at all day long” in a traditional classroom. The Acton Academy’s mission is “to inspire each child and parent who enters [its] doors to find a calling that will change the world.” The school promises that students will embark on a “hero’s journey” to discover the unique contributions that they can make toward living a life of meaning and purpose.

With tuition of $9,515 per year, Acton Academy initially enrolled 12 students and has since 2009 grown to serve 75 students in grades 1 to 9. The school has learning guides—they aren’t called teachers—whose role is to push students to own their learning. The model enables the academy to have far fewer on-site adults per student than a traditional independent school and to operate at a cost of roughly $4,000 per student per year.

Acton compresses students’ core learning into a two-and-a-half-hour personalized-learning period each day during which students learn mostly online. This affords time for three two-hour project-based learning blocks each week, a Socratic seminar each day, game play on Fridays, ample art and physical education offerings, and many social experiences.

The Socratic discussions teach students to talk, listen, and challenge ideas in a face-to-face circle of peers and guides. The projects require the students to work in teams to apply the knowledge they have learned. They also foster a ‘‘need to know’’ mind-set to motivate the online learning and provide a public, portfolio-based means for students to demonstrate achievement.

Early results appear impressive, as the first group of students gained 2.5 grade levels of learning in their first 10 months. Now the school is spreading. There are currently eight Acton Academies operating—seven of them in the United States. Twenty-five are slated to be open by 2015. The Sandefers are not operating them, however; they provide communities that want to open an Acton clone a do-it-yourself kit plus limited consulting and access to wiki discussion groups. They are developing a game-based learning tool to help prepare Acton Academy owners and the learning guides in the schools. Tuition at the academies ranges from $4,000 per year to $9,900.

Inspired in part by micro-schools like Acton Academy that use his software, the prince of online and personalized learning himself, Sal Khan, launched his own micro-school in the fall of 2014 in Mountain View, California. The Khan Lab School, which charges $22,000, opened with roughly 35 students and intends “to research blended learning and education innovation by creating a working model of Khan Academy’s philosophy of learning in a physical school environment and sharing the learnings garnered with schools and networks around the world.”

As Isabella, an 11-year-old student who previously attended a nearby public school, said, “Here it’s different from my old school because you’re doing your own playlist and you have more projects.”

Mandeep Dhillon, a parent with two children enrolled at Khan Lab School, amplified the differences.

“After a while, we realized public, private school didn’t matter. Kids were being programmed in chunks,” he said. “I hate the term home schooling because it’s based on location. It’s not really about having them at home. What we’re trying to do is build an independent path. It’s not about the schooling, it’s about experiences.”

As these small schools proliferate, their impact on the wider world of schooling—public and private—is potentially large, but still anything but certain.