Blossom Montessori School for the Deaf has served students for more than two decades. Photo courtesy of Blossom Montessori School for the Deaf

CLEARWATER, Fla. – More than 20 years ago, Julie Rutenberg and Colette Derks harnessed some of the first private school choice programs in America to create a bespoke little school they knew their community needed. All these years later, Blossom Montessori School for the Deaf continues to show what kind of diverse, ever-expanding options are possible when education choice is in the mix.

Rutenberg founded Blossom in 2003. Derks, now the associate director, helped stand it up. As the name suggests, the PreK-6 school serves students who are deaf or hard of hearing (along with their siblings) and the children of deaf adults. Occasionally, Blossom also serves students who do not have any hearing loss because their parents want them to have more one-on-one attention. Over the years, nearly every one of its 250-plus students used a state-funded choice scholarship.

Rutenberg and Derks were working at a community center for deaf people when they got the idea for the school. They thought the hands-on, self-directed, mastery-based approach of Montessori offered a good alternative to the students they saw having a tough time in traditional schools.

“They’re able to move around the manipulatives when they’re working out their (math) problems, when they’re building words for reading, working with writing skills,” Derks said. “We really love how Montessori just kind of gets the whole body involved when learning.

“You’re not just sitting at a table looking at a paper or a book all day, (where) everybody’s on the same level,” she continued. “It really helps the student to be able to kind of grow and develop at their own pace.”

Rutenberg and Derks praised the public-school programs in their area that are serving similar students. Offering an option, they said, is not a knock on them.

“We’re just a different way of learning,” said Rutenberg, who attended Montessori schools as a child. “We’re not always going to be the right fit, either. Our goal is just to make sure the child comes first.”

Blossom got its start using three rooms inside another Montessori school. But for most of its existence, it’s been housed in a trim, beige building in an eclectic office park, right next to an ice-skating rink.

Most of the families it serves are working class. Most live in the immediate area. Some, though, drive an hour or more each way so their kids can attend. Others have moved from as far as Daytona Beach – on the other coast of Florida – because they wanted the school that much.

Quinten Caroline, 7, in costume as Leonardo DaVinci as part of a school project on Italy. Photo courtesy of Blossom Montessori School for the Deaf

“It’s nothing but positive with everything they do. They see the kids as perfect the way they are,” said Anastasia Caroline, whose son Quinten, 7, attends Blossom. “In a normal school, you’re not always going to get that love, that acceptance.”

Blossom represents so many choice-fueled trend lines. It’s a microschool. It’s a Montessori school. It’s a school for students with special needs. In Florida, where choice is the new normal, all those options are growing.

Microschools are so much of a thing now, they’re routinely showing up in local news stories (like this one and this one). I don’t know if anybody has a good handle on the total number, in part because there isn’t an official definition. But Microschool Florida, an excellent resource, puts the number at 156 and counting.

A student says "I love you" in American Sign Language. Photo courtesy of Blossom Montessori School for the Deaf

Meanwhile, there are at least 150 private Montessori schools participating in Florida’s choice programs. I say at least because that’s how many are listed in the state’s private school directory with Montessori in their name.

To be sure, there are plenty of Montessori-influenced private schools that don’t have Montessori in their names (like this one, this one, and this one). There are also plenty of school-like entities, like this hybrid operation in Tampa, and this homeschool co-op in South Florida, that are Montessori influenced, but aren’t official private schools, and aren’t tracked in any kind of official way, yet are funded in part by parents using flexible, state-funded education savings accounts.

Finally, there are more options for students with special needs. There’s more inclusion because more families can now afford schools that were once out of reach. (Check out, for example, the trend lines for scholarships for students with unique abilities in our white paper on Catholic schools.)

At the same time, there are more specialized schools, because, with choice, education entrepreneurs can more easily create them. Not far from Blossom, schools like this one, this one, this one, and this one, are all thriving.

“We would not be here today if we didn’t have the opportunity to use the choice scholarships,” Derks said. “It really is so important because the world today tries to fit everybody into the same box. (But) we’re all individuals, and we’re all our own person, and we learn differently, and we grow differently.”

Caroline, who works as an office manager at a medical practice, secured choice scholarships for both her sons, Quinten, and Silas, 10. She said private school would not have been possible otherwise.

Both use the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities, an ESA Florida created in 2014. Once called the Gardiner Scholarship, it now serves 122,000 students. (Prior to the FES-UA Scholarship, Florida had a scholarship for students with special needs called the McKay Scholarship. It was merged with the FES-UA Scholarship in 2022.)

Caroline said she chose Blossom because she wanted Quinten immersed both in a sign language program and in the tight-knit deaf community. The school provides the warmth, structure, and positive reinforcement he needs, she said.

“They don’t allow bullying. They don’t put kids down. They just celebrate their growth and watch them blossom,” Caroline said. “It’s completely an amazing school for my child.”

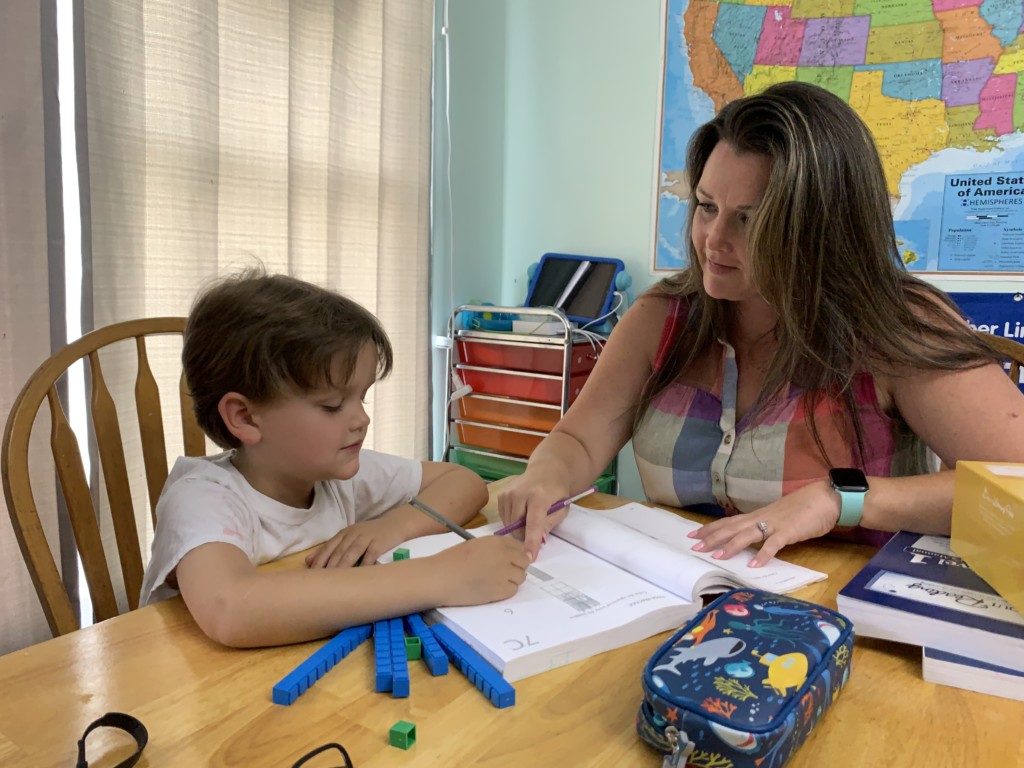

Sandra Shoffner of Wauchula works with her son, Elliott, at the family's dining room table using materials she purchased with her education savings account.

Surrounded by orange groves, Wauchula, Fla., the Cucumber Capital of the World, would seem an odd perch to check out the future of public education. But that’s exactly what little Florida towns like this one are offering.

Wauchula, population 5,001, is home to homeschool mom Sandra Shoffner and her 6-year-old Elliott, who is on the autism spectrum. For the past two years, Shoffner has used a state-funded education savings account, or ESA, to carefully cobble together a learning program for her son.

Her remote county 70 miles southeast of Tampa has five public elementary schools and two private schools. But home education supplemented by an ESA, she said, is a far better fit for her son.

“It’s working fantastically,” said Shoffner, a mother of four with degrees in elementary education and special education. “I’d homeschool regardless. But (Elliott’s) special needs make it that much more important to be there with him, and for him, and to reach these milestones.”

“There are so many options with this scholarship,” she continued. “Without it, I’d have a fraction of this.”

Shoffner isn’t trailblazing alone. Thousands of DIY moms and dads all over Florida – and, it turns out, particularly in rural Florida – are redefining and reimagining education right along with her.

According to this new report, ESA parents in rural Florida are more likely than their counterparts in cities and suburbs to access multiple services from multiple providers. In other words, parents from Live Oak and Arcadia are more likely than parents in Orlando and Miami to mix and match services a la carte and fully customize their child’s education.

“Distribution of Education Savings Accounts Usage Among Families,” by Michelle Lofton of the University of Georgia and Martin Lueken of EdChoice, examined the spending patterns of families using Florida’s Gardiner Scholarship, an ESA created in 2014 for students with special needs. The scholarship is the nation’s largest ESA program, serving 17,508 students last year. It’s administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

According to the study’s definitions, about a third of Gardiner students are in rural settings or small towns like Wauchula. This is where it gets especially interesting.

Unlike a traditional “school choice” scholarship, an ESA isn’t limited to private school tuition. It also gives parents the power to purchase curriculum, technology, therapies, tutoring and other educational materials and services – and the flexibility to line them up in any way that works best for their child.

The new study found the longer students remained on the Gardiner Scholarship, the more likely their parents would access other programs and services beyond paying tuition. It also found parents in rural communities were making more frequent purchases, in more categories of spending.

“These observations,” the report said, “support the notion that rural students, who may have access to fewer educational offerings in not only schools but also course offerings compared to urban and suburban students, may especially benefit from education savings accounts.”

These observations might also help chip away at a persistent myth – that school choice and education choice aren’t viable in flyover country.

In Florida, which offers as many learning options as any state in America, it’s not hard to find charter schools, and private schools that accept choice scholarships, thriving off the beaten path. As the new study confirms, ESA parents are finding fertile ground here, too.

After her two oldest had less-than-ideal experiences in traditional school, Shoffner decided to do what her heart told her in the beginning: home school.

“I wanted to raise them and educate them,” said Shoffner, who works part time as executive director of the Hardee County Friends of the Library. “I didn’t see the point of sending them to somebody else to educate them, when I could do it and I wanted to do it.”

Even with that experience, though, Shoffner said she and her husband, a graphic designer, wouldn’t have been able to provide Elliott the supports and services he needs without the ESA.

Elliott is benefiting from Florida's Gardiner Scholarship, which allows his parents to mix and match services and providers to customize his education.

Shoffner used the scholarship funds to purchase a tablet and a printer for Elliott, who takes particular pride in doing digital art and printing his creations in color. She bought a complete curriculum with scripted lessons, something she learned was vital from homeschooling her two oldest, now 17 and 14. She also acquired physical education tools, including an indoor trampoline and a Jumparoo, to help Elliott work on motor skills and channel excess energy.

Shoffner said she is just scratching the surface of what’s possible with the ESA. In coming years, she plans to use the funds for multiple therapies for Elliott. She also wants to hire an instructor who can cultivate Elliott’s finely tuned ear for music.

Elliott can recognize a song after a few notes, whether it’s a classical score or “Careless Whisper,” and quickly differentiate sounds in music dense with multiple instruments.

“There are layers of instruments that I don’t hear,” Shoffner said. “He’ll say, ‘Do you hear the little teh teh teh teh?’ No, I don’t. But he does.”

If they keep their ear to the ground in Florida, people keeping tabs on changes in public education might hear some unexpected things, too – and from some unexpected places.

Families interested in learning more about the Gardiner Scholarship program can click here for more information.

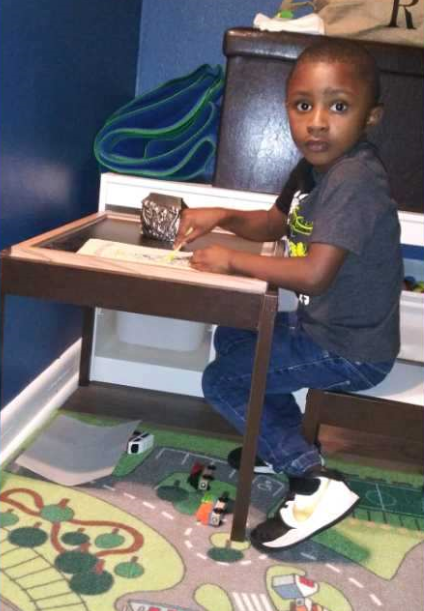

Urrikka Woods-Scott was able to create a sensory environment for her son, Roman, in his bedroom thanks to her Gardiner Scholarship’s education savings account.

Roman Scott’s bedroom has two walls painted orange and two painted blue. On the floor is a rug with the design of a two-lane road wending its way through a small town.

A train set sits on the rug, because Roman, 4, loves trains. And there is a stack of trays that hold his toys and musical instruments, because Roman loves to, as his mom says, “rock out” on his tambourine, cymbals and triangle.

Urrikka Woods-Scott refers to this as a “sensory room” for her son, who is on the autism spectrum.

“The goal was to get him to engage in his room, love his room by having all the support in that room,” she said.

Urrikka Woods-Scott and her son, Roman

Roman receives the Gardiner Scholarship for children with special needs. (The scholarship is managed by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.) Many of the items in Roman’s room, including the educational toys from Melissa & Doug and the stack of books from the Frog and Toad series, were purchased with funds from the Gardiner’s education savings account. These flexible spending accounts allow parents to use their children's education dollars for a variety of educational purposes.

The scholarship also pays for Roman’s therapy at Bloom Behavioral Solutions, which is near their home in Jacksonville, Florida.

Woods-Scott got the idea to turn Roman’s bedroom into a sensory room from Bloom. She learned what Roman gravitates to in Bloom’s sensory room and did her best to replicate those items at home.

“We’re trying to transition (him) from sleeping in my bed to sleeping in his own bedroom,” Woods-Scott said. “I want him to have what he needs to be comfortable in his own room. My thought was to make his room a destination.”

Woods-Scott’s husband, Romain, suggested the colors for the walls. Orange and blue are two of Roman’s favorites. Blue is considered soothing and is a popular choice for sensory rooms. Woods-Scott added brown curtains to give the room more life.

The results, she said, are beyond encouraging.

Woods-Scott said Roman has made great strides since joining the Gardiner program in 2020. Much of that comes from his time at Bloom, which he attends for 30 hours a week. The rest comes from the tools available at home that Woods-Scott purchased through MyScholarShop, Step Up For Student’s online catalog of pre-approved educational products.

Families also can purchase items or services that are not on the pre-approved list. They must submit a pre-authorization request that includes supporting documentation and an explanation of how the purchase will meet the individual educational needs of the student.

A review is then conducted by an internal committee, which includes a special needs educator, to determine if the item or service is allowable under the program’s expenditure categories and spending caps, and a notification is sent to the parent. The item or service may then be submitted on a reimbursement request that must match the corresponding pre-authorization.

Step Up For Students employs numerous measures to protect against fraud and theft, such as ensuring a service provider’s reimbursement request and a parental approval came from different IP addresses.

Woods-Scott purchased an iPad on MyScholarShop, which Roman uses for speech, math and preschool prep. She buys arts and craft supplies because they help Roman improve his fine motor skills.

Roman was diagnosed in October 2019. The family was living in Charlotte, North Carolina at the time. That November, Woods-Scott changed jobs and the family moved to Jacksonville, where, unbeknownst to her, Roman was eligible for the Gardiner Scholarship, the largest education savings account program in the nation.

At the time, Roman was a “scripter,” which meant his speech was limited to repeating what he heard on a television show or a movie.

Roman's customized bedroom includes a trampoline to help him with balance and coordination.

“It wasn’t a functional type of speech and he wasn’t expressing what he needed,” Woods-Scott said. “He wasn’t saying, ‘Mom, I want a banana,’ or something like that. He was only saying what he heard on a show. Now he says ‘mommy’ and ‘daddy.’ He tells you what he wants.”

Roman can count to 100 and recite the alphabet. He can read his Frog and Toad books out loud.

Next year, Woods-Scott would like to use her Gardiner funds to send Roman to the Jericho School of Autism in Jacksonville.

After having what she called “my little moment of crying” when Roman was diagnosed with autism, Woods-Scott went to work seeking therapy for her son and advocating for those on the spectrum. She started Mocha Mama on FIRE, a YouTube vlog that promotes autism awareness in the Black community.

And, she has started the nonprofit Shades of Autism Parent Network to focus on multicultural parents of children on the spectrum and create recreational experiences through travel.

Woods-Scott knows how fortuitous it was to land the job in Florida, and what that meant for Roman.

“It was definitely all for a purpose,” she said.