Tag: Blaine Amendments

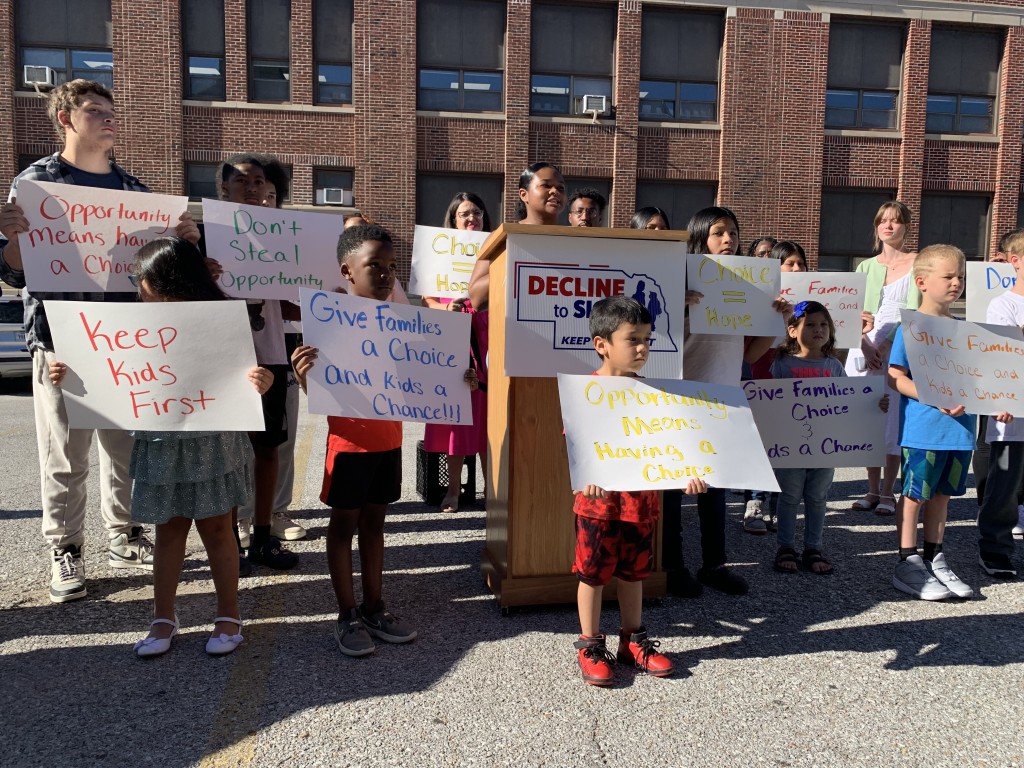

Despite setbacks at the ballot box, young education choice alum vows to continue the fight for parent-directed education

Jayleesha Cooper sat in her apartment at the University of Chicago and watched with hope as the election results rolled in. The college senior from Omaha had marked her mail-in ballot to retain Nebraska Measure 435, upholding a $10 million tax credit Opportunity Scholarship program state lawmakers passed a year... READ MOREUtah becomes the latest battleground in the fight over education savings accounts

The headline: Utah’s largest teachers union filed a lawsuit against...

READ MOREDespite landmark court rulings, ‘Blaine amendments’ keep causing education controversies

Your guide to the intersection of school choice, the courts and the...

READ MORENew report shows how Massachusetts could adopt education savings account program

Editor’s note: This commentary from Tim Benson, a policy analyst...

READ MOREProposed federal Title IX rules ripped by DOE’s Diaz, schools in brain health program, and more

READ MOREIn Espinoza’s wake, is the Blaine bane at risk?

“Like to one more rich in hope.” Twelfth Night, Shakespeare...

READ MOREKomer saved the best for last

Bigots spent an enormous amount of effort in the late...

READ MORECourt lays to rest age-old debate with Espinoza decision

After more than a century, the U.S. Supreme Court finally...

READ MORECourt ruling eases way for public money to go to religious schools, desk barriers, masks and more

READ MORESenate committee’s teacher pay proposal, carrying on campuses, restricting restraints and more

Teacher raises: The Florida Senate Education Committee has released its...

READ MOREEspinoza may not be the game changer some are predicting

It seems especially appropriate midway through National School Choice Week...

READ MORE